Parson Weems Fights Fascists

G. W. and the cherry tree in 1939

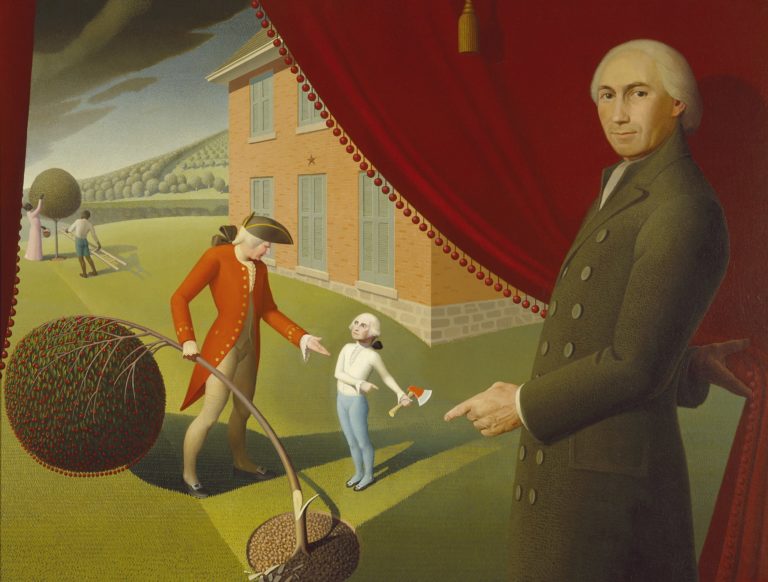

Parson Weems, imitating Charles Willson Peale’s pose in The Artist in His Museum (1822), opens a red velvet curtain on the legendary scene: Augustine Washington, elegant in crimson coat, white ruffle, tan breeches, silver-buckled pumps, and green tricornered hat, grasps in his right hand the slim trunk of the bent cherry tree. A row of cherries dangles from the perfectly rounded treetop, mirroring the very cherry-like fringe of the Parson’s curtain. Augustine’s outstretched left palm and furrowed brow signal a serious inquiry. His son George, boyish in stature and dress—coatless, with sky-blue breeches and petite buckled pumps—is manly in his expression. In fact, his white-wigged head is that of Gilbert Stuart’s portrait and the dollar bill. He points with his right hand to the hatchet in his left. Wood chips lie in the circle of soil at the base of the tree, its lower trunk smoothly incised and poised to split off. In the background, a well-dressed slave couple harvests the fruit of a second tree.

The man behind the man behind the curtain is Grant Wood, forty-eight years old when he painted Parson Weems’ Fable in 1939 and perhaps the best-known artist in the United States at the time. The Washingtons’ shuttered brick house is Wood’s house in Iowa City. The rolling hills and the precisely spaced spherical trees in the background are those of Iowa or at least the Iowa of Wood’s own well-ordered landscapes. The Parson and Augustine Washington are modeled on two of Wood’s University of Iowa colleagues. George is modeled on the nine-year-old son of the colleague who posed for Augustine.

Sudden fame had come to Wood late in 1930, when American Gothic took third prize at the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual competition. Critics immediately praised it as a sharp send-up of small-town or rural life, and newspapers reprinted it across the country. After that, each of Wood’s major paintings—and his pronouncements about American art and culture—had been greeted with eager media attention. Parson Weems’ Fable, ballyhooed by Time as “artist Wood’s first big canvas in three years,” immediately sold to the novelist John P. Marquand for ten thousand dollars (about one hundred and thirty thousand dollars today). Wood had come a long way in the nine years since the Art Institute bought American Gothic for three hundred dollars.

Seen as a satirist when American Gothic first appeared, Wood had refashioned himself by the mid-1930s as an outspoken celebrant of the heartland and of healthy, “native” art. No longer was he under the spell of H. L. Mencken and Sinclair Lewis, with their “contempt” for “the hinterland” and their “urban and European philosophy.” He and many other citizens, he proclaimed, had embraced an “American way of looking at things.”

“The Great Depression has taught us many things, and not the least of them is self-reliance. It has thrown down the Tower of Babel erected in the years of a false prosperity; it has sent men and women back to the land; it has caused us to rediscover some of the old frontier virtues. In cutting us off from traditional but more artificial values, it has thrown us back upon certain true and fundamental things which are distinctively ours to use and exploit.”

Among these things were national myths and legends, few if any of which were more familiar than the fable of George Washington and the cherry tree.

The cherry-tree story first appeared in 1806, in the fifth edition of Mason Locke Weems’s A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington, originally published as an eighty-page pamphlet in 1800. By 1808, the sixth edition had swollen into a book of over two hundred pages. Twenty-three more editions followed by the time Weems died in 1825. The “Parson” was an Episcopal minister who hit the road as a book peddler around 1791 and, over the next thirty years, constantly traveled the mid-Atlantic and southern states to create what one of his biographers called “a national reading public.” Weems explained his motives to the Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey: “This country is large and numerous are its inhabitants[.] [T]o cultivate among these a taste for reading, and by the reflection of proper books, to throw far and wide the rays of useful arts and sciences, were at once the work of a true Philanthropist and a prudent speculator.” The Life of Washington, as it came to be known, epitomized this happy combination of moral instruction and steady profits. (In much less elevated terms, he advised Carey in 1809, “You have a great deal of money lying in the bones of old George if you will but exert yourself to extract it.”)

As far as moral instruction goes, it’s worth noting the context in which the cherry-tree story appears in Weems’s book. Young George is prepared for his legendary truth-telling episode by a particularly strong dose of his father’s didacticism. Unprompted by any bad behavior on George’s part, Augustine tells the boy that he’d rather see him dead than “a common liar.” “Oh George! my son!” he exclaims, “rather than see you come to this pass, dear as you are to my heart, gladly would I assist to nail you up in your little coffin, and follow you to your grave. Hard, indeed, would it be to me to give up my son, whose little feet are always ready to run about with me, and whose fondly looking eyes, and sweet prattle make so large a part of my happiness.” Thereupon follows the anecdote:

“George,” said his father, “do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry tree yonder in the garden?” This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself: and looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, “I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet.”

A tough question, indeed, given that the alternative to a truthful answer was death.

Thanks to Weems’s itinerancy and salesmanship, the fable circulated nationwide even before McGuffey’s Readers picked it up and succeeding Washington biographers canonized it. No doubt it was still a staple of moral instruction in Iowa’s public schools when Grant Wood was a boy. But by the 1930s, it had also been thoroughly debunked. Historians and critics in the 1910s and 1920s delighted in outdoing one another’s dismissals of the Parson’s work: “grotesque and wholly imaginary stories,” “pernicious drivel,” “a mass of absurdities and deliberate false inventions,” a “slush of plagiarism and piety,” “beneath contempt or criticism.” The editor’s note to a 1927 reprinting of The Life of Washington pointed out that after having run through almost seventy editions and having successfully instilled “the popular legend of Washington” in “millions of American minds,” the book had “died a natural and deserved death.” The modest aim of the reprinting, he said, was simply to preserve “one of the most interesting, if absurd, contributions ever made to the rich body of American legend.”

Only as a piece of folklore did the cherry-tree story still have some life. Harold Kellock, author of a 1928 biography of Weems, made clear his bemusement with his subject in his antiquated title, PARSON WEEMS OF THE CHERRY-TREE; Being a short account of the Eventful Life of The Reverend M. L. Weems, AUTHOR OF MANY BOOKS AND TRACTS, ITINERANT PEDLAR OF DIVERS VOLUMES OF MERIT: PREACHER OF VIGOUR AND MUCH RENOWN, AND FIRST BIOGRAPHER OF G. WASHINGTON. In a bit of Weemsian exaggeration, Kellock remarked that “the story of Washington and the cherry-tree, which is familiar to children along the upper reaches of the Amazon and the Yangtze . . . is perhaps the most widely known folk-lore in any tongue.” But it was also a curious kind of folklore, as Kellock tacitly acknowledged. It wasn’t “distilled from native legends.” It wasn’t a recording of oral traditions, even though Weems fabricated a tale about hearing it from “an aged lady” who had been a slave in Augustine Washington’s household. Rather, it was a “product of [Weems’s] own fecund imagination” that “rolled into the word from his quill pen.” This was folklore that didn’t grow out of the folk or out of any particular place but from the mind of a famous book peddler and from the pages of his national bestseller. Quaint though Weems and his story seemed in the 1920s and 1930s, they hardly emerged from the conditions laid out by the influential folklorist Benjamin A. Botkin in 1934: “Folk groups are distinguished by cultural isolation. The folk, like the primitive, group is one that has been cut off from progress and has retained beliefs, customs, and expressions with limited acceptance and acquired new ones in kind.” Even when he adopted a more expansive conception in A Treasury of American Folklore (1944)—and included the cherry-tree episode from Weems’s book in the anthology—Botkin argued that “folklore is most alive or at home out of print” and that “its author is the original ‘forgotten man.’”

The Depression and World War II heightened the appeal of folklore as the enduring “germ-plasm of society” and hence a resource for survival in difficult and uncertain times. But it would have been preposterous to see the cherry-tree story as an organic outgrowth of “a continuous life of the folk running through the history of the nation,” “rooted in nature,” “a wild plant,” or “hardier and more fit to endure than any form of the cultivated life” as other folklorists described their subject. What to make, then, of a thoroughly debunked piece of inorganic folklore?

Grant Wood, for one, recommended a strategy of knowing acceptance, somewhere between credulity and cynicism. In his view, offered in the form of a press release issued for the painting’s public debut, the cherry-tree story was at once too good to be true and “too good to lose.”

“It is, of course, good that we are wiser today and recognize historical fact from historical fiction. Still, when we began to ridicule the story of George and the cherry tree and quit teaching it to our children, something of color and imagination departed from American life. It is this something that I am interested in helping to preserve.

As I see it, the most effective way to do this is frankly to accept these historical tales for what they are now known to be—folklore—and treat them in such a fashion that the realistic-minded, sophisticated people of our generation accept them.”

Aside from the formal and art-historical reasons for the Parson’s position in the painting’s foreground, his opening of the curtain lets viewers in on the scene as knowing participants in the fabrication. He points to the cherry tree with his left hand and smiles wryly. He shares a sense of irony with his “sophisticated” viewers, but he also conveys his honest affection for the tale he’s telling. And Wood, too, insisted that his underlying intentions were earnest. “I sincerely hope that this painting will help reawaken interest in the cherry tree tale and other bits of American folklore,” he said. Parson Weems’ Fable reveals its layers of inauthenticity—the contemporary artist creates a faux-Peale image of a clever author making up a story about not telling lies—only to help revive the legend for a “present, more enlightened generation.”

What was at stake, aside from preserving “color and imagination,” in reawakening interest in this bit of American folklore? Certainly not old-fashioned moral instruction. Wood’s Weems can’t possibly believe in his own book’s “pious mendacities” and “cloying moral lessons” (as Kellock described The Life of Washington). But the contemporary value of the cherry-tree story didn’t have to reside in its didactic content. “In our present unsettled times,” Wood explained in his press release, “when democracy is threatened on all sides, the preservation of our folklore is more important than is generally realized.” Citing a recent Atlantic Monthly article by the Harvard English professor Howard Mumford Jones titled “Patriotism—But How?” Wood worried that “while our own patriotic mythology has been increasingly discredited and abandoned, the dictator nations have been building up their respective mythologies and have succeeded [in Jones’s words] in ‘making patriotism glamorous.’” A democratic national mythology was necessary to fight totalitarianism, yet the content of that mythology, observes the art historian Cécile Whiting, was much less important to Wood than the commitment to mythmaking itself. Following the historian and folklorist Constance Rourke—who, Whiting notes, “considered both fablemaking and humor to be uniquely American character traits”—Wood saw the knowing and willing acceptance of myths like the cherry-tree story as an alternative to the dangerous credulity demanded by the patriotic mythologies of Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and the Soviet Union. Self-aware engagement in the process of mythmaking rather than believing in the myths themselves would have to serve as America’s cultural response to the “dictator nations.” Parson Weems’ Fable fostered patriotism by taking the national “trait” of mythmaking as its subject. Only at this remove from the cherry-tree story’s obvious falsity could it serve as one of those “true and fundamental things which are distinctively ours to use and exploit” in resisting totalitarianism.

This conception of patriotism—in which national identity is based to a significant extent on a shared sense of irony and humor—was subtle, and not all of the painting’s viewers got it. Life reproduced Parson Weems’ Fable in full color in its February 19, 1940, issue. The accompanying article eagerly reported on the controversy the painting had already stirred up.

“Almost before the paint was dry on this picture it started a battle. Widely publicized as the first painting by Grant Wood in three years, and one of his new series on American folklore, it recently raised the dander of literal-minded patriots all over the country. They bombarded Wood with angry letters because he depicted the cherry-tree story frankly as a fable invented by Parson Weems, and accused him of “debunking” Washington.”

Viewers’ anger was old hat to Wood by then. He owed his fame in part to the irate responses of Iowa farmwives to American Gothic, a few of whom, he reported, had threatened to bash his head in for portraying them as homely and dour. His Daughters of Revolution, a 1932 portrait of three self-righteous patriotic matrons in front of Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, had also provoked a backlash, this time from the D.A.R.

In the case of Parson Weems’ Fable, it was Wood’s own advance hyping that got him into trouble. Nine months before he put brush to canvas, he announced in an interview that honest young George “has got to be smug.” The idea that the Father of the Country would be depicted in such a way riled the humorless editors of the Indianapolis News, who contended that the hero who adventurously set off on a western survey at sixteen couldn’t possibly have been smug at six. “Little is known of Washington’s boyhood,” they lectured, “but if that little proves anything conclusively, it is that he was not a smug boy.” The Chicago Tribune reprinted the Indianapolis paper’s editorial and offered up a more scathing one of its own. Young George would be painted as smug “only because Wood is smug,” intoned the Tribune, and this attitude was typical of artists like Wood who worked for the New Deal’s arts projects. These “parasitic” pinkos, “whose pleasure it is to belittle great men, pretending to correct our memories out of their shallow thought and twisted tempers,” were “supposed to foster American art” but instead produced the equivalents of “mural paintings of Lenin at Valley Forge or Stalin crossing the Delaware.” Parson Weems’ Fable would be another of Wood’s “malicious cartoons,” like American Gothic, which almost everyone but the Tribune editors had long since come to see as a celebratory image of American steadfastness and determination. (Three years later, the Tribune finally came around when it reprinted American Gothic as a morale booster for the World War II home front. American Gothic’s couple now represented a “fixed belief in a better tomorrow . . . an undying patriotism . . . a readiness to sacrifice, that their sons and daughters might go forward!”)

No wonder Wood was ready with his press release as soon as Parson Weems’ Fable was finished. “Grant Wood is an earthy, peaceable Iowan who manages to stir up many an artistic rumpus,” Time reported only two weeks after Wood sent the completed painting to his dealer in New York. According to Time, Wood “placidly ignor[ed] the storms such paintings raise,” but his sister Nan—the model for the woman in American Gothic—recalled that the criticism stung him. Besieged from the right by “literal-minded patriots,” he had also been hammered from the left for what the New Masses called his “frantic patrioteering” and “national chauvinism.”

Wood’s “new series on American folklore” started and ended with Washington and the cherry tree. He announced but never painted his version of the John Smith-Pocahontas legend, and his subsequent statements about a proper patriotic art were not as nuanced as those that accompanied Parson Weems’ Fable. In the spring of 1941, he insisted that art had an important role to play in national defense: not “flag-waving” art with “screaming eagles and goddesses of liberty upholding flaming torches” but not “smart, sophisticated stuff” either; just paintings of “the simple, everyday things that make life significant to the average person.” Wood’s last two paintings before his death in February 1942 were titled Spring in the Country and Spring in Town. Both depicted robust midwesterners working their bounteous fields and gardens. Neither contained even a hint of irony.

Had he been alive to read the October 1955 issue of Western Folklore, Wood might have taken heart. There he would have encountered two versions of the cherry-tree story from Texas, collected by the folklorist George D. Hendricks. The first had the Washingtons living in a “modest cottage on the north bank of the Rio Grande.” It is Christmas morning, and little George is thrilled to discover Santa’s gift of a new machete. He rushes out to hack down his father’s favorite huisache tree. The following exchange ensues:

“George, I want you to tell me the truth. Did you or did you not cut down my favorite huisache tree?”

George looked him right in the eye. “Sir, I cannot tell a lie. I cut your favorite huisache tree down with my own little machete.”

“Well, George, I must say that I am really disappointed in you; and there’s only one course left open to me now. I can see that if you cannot tell a lie, you’ll never make a good Texan. I’ll have to take you back to Virginia.”

The second version involves a boy and his father on a farm near the Neches River. The back end of their privy extends out over the river on stilts. One day, after the boy is punished for playing hookey, he takes his revenge by chopping down the privy with his axe. He fesses up to the deed.

“[I]t was me who cut down the privy. I done it with my own axe. I’ll behave now if you promise me you won’t lick me.”

The father glared at his offspring, “I’ve a mind to give you a larrupin’.”

“But, paw, remember George Washington told his paw he cut down the cherry tree and he never got no lickin’.”

“I know. But this here’s a powful sight different. When George cut down the cherry tree, his paw warn’t UP IN THE TREE!”

Here was “color and imagination” galore and not necessarily among those whom Wood envisioned as “the realistic-minded, sophisticated people of our generation.” Here was folklore restored to the kind of oral culture from which it was supposed to derive. Here was Parson Weems’s fable at once embraced and debunked, retold with both affection and irony, acceptance and knowingness.

Further Reading:

There are two superb comprehensive studies of Grant Wood’s life and work: James M. Dennis, Grant Wood: A Study in American Art and Culture (New York, 1975; revised edition, Columbia, Mo., 1986) and Wanda M. Corn, Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (New Haven and London, 1983). Both include illuminating discussions of Parson Weems’ Fable. I am particularly indebted to Cécile Whiting, “American Heroes and Invading Barbarians: The Regionalist Response to Fascism,” in Jack Salzman, ed., Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies, Vol. 13, (Cambridge and New York, 1988): 295-324. Karal Ann Marling traces the debunking of the cherry-tree story in George Washington Slept Here: Colonial Revivals and American Culture, 1876-1986 (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1988). In contrast to Dennis, Corn, and Whiting, Marling sees Parson Weems’ Fable as an unambiguous work of debunking; in her view, little George is indeed a “smug little brat,” and the painting treats Washington as “a bit of an embarrassment, a national joke.” The Texas versions of the cherry-tree story are recounted in George D. Hendricks, “George Washington in Texas, and Other Tales: Old Stories in New Surroundings,” Western Folklore, Vol. 14, No. 4 (October 1955): 269-272. For information about Weems, I especially drew on: Lewis Leary, The Book-Peddling Parson: An Account of the Life and Works of Mason Locke Weems, Patriot, Pitchman, Author and Purveyor of Morality to the Citizenry of the Early United States of America (Chapel Hill, 1984) (evidently, it is a requirement of the Parson’s biographers that they use verbose, antiquated subtitles); Ronald J. Zboray, “The Book Peddler and Literary Dissemination: The Case of Parson Weems,” Publishing History, Vol. 25 (1989): 27-44; and Steven Watts, “Masks, Morals, and the Market: American Literature and Early Capitalist Culture, 1790-1820,” Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Summer 1986): 127-150.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.4 (July, 2006).

Steven Biel is the executive director of the Harvard Humanities Center and author of American Gothic: A Life of America’s Most Famous Painting, just out in paperback from W. W. Norton.