Partners in Time

Dancers, Musicians, and Negro Jigs in Early America

I met ethnomusicologist Greg Adams at a conference on African Atlantic culture, history, and performance held in June 2012 on the University of Maryland’s College Park campus. He introduced himself as an “early banjo” player who was eager to hear what I had to say about “Negro jig dancing.” Greg introduced me to dancer-choreographer Emily Oleson, who combines historical and contemporary forms of vernacular dance. And when Roberta Perkins, Delaware state parks historian and student of the bones, joined us, we became an inseparable crew, hanging out between sessions talking about the sort of people who played and danced jigs. In 1840s America, those people were white and black, male and female, old and young, just like the four of us.

Negro jigs were produced by competition and cooperation among African and Irish musicians and dancers, who met and interacted throughout the Atlantic world. They represent one of many instances when white and black people communicated through culture and created something new to identify with individually and as communities. The exchange of dance practices among African and Irish Americans in the 1840s is the topic of my current research. However, meeting Greg and Emily, two young scholars who collaborate on historical music and dance projects for Harpers Ferry National Park, inspired me to look more closely at the relationship between musicians and dancers performing Negro jigs.

Unfortunately, recovering the history of music and dance is not easy. Part of the problem lies in the nature of the sources, which epitomize the inherent difficulty of putting will o’ the wisps like melody and movement into words. Dance scholars like Jacqui Malone and Constance Valis Hill have used their experience as performers to explain the non-verbal practices and lineage of moves and steps that dancers pass on one to another. They translate kinesthetic information into words that both historians and dancers can mine. Dancers and musicians, who work primarily with physical knowledge and sensation, perceive jigs differently than historians who rely on written evidence. They can break down a complex move or melody, analyze patterns, compare features, and, with enough historical knowledge, reconstruct performance styles and techniques.

Even more elusive are the meanings people gave to their music and dance. Most nineteenth-century documents describing Negro jigs are stained by the writer’s racial and class prejudices, or, even worse, written by someone with no dancing or music-making experience. While often rich in detail, these sources do not explain why people danced and played music the way they did. To find that out, we need the perspective of the performers, and since nineteenth-century jig dancers didn’t write very much, that evidence is meager. One way to enrich it is to communicate with today’s practitioners or, even better, experience the dancing and music-making ourselves. Performers versed in the parent forms of Negro jig dancing (African and Irish challenge dance) or its offshoots (tap and flatfoot dancing) will notice details that elude non-dancers, details that often counter the meaning attributed to Negro jigs by the authors of written sources. They recognize through experience something historians find tough to explain—that even in a society characterized by racial antipathies, black and white people willingly shared their cultural practices.

African and Irish emigrants uprooted from their homelands by economic and political aggression met and mixed in slave ships and plantation fields, city streets and cellar taverns, farmhouse kitchens and prison cells. But it wasn’t just poverty and displacement that brought them together in the New World. It was likenesses in their music and dance traditions. In western regions of Ireland and Africa, from which most of North America’s Irish and African populations came, dance and music were a part of everyday life. Not everyone in the old country was good at playing music or dancing, but everyone participated. These similar backgrounds offered people with different languages and cultures chances of communication.

But African and Irish musicians and dancers played and moved in very different ways. So how did they come together?

For one thing, their dance and music practices shared a variety of translatable elements. In both cultures, people trained with master dancers and musicians, learned to improvise, and held competitions. But what made them truly compatible was their understanding of the relationship between music and dance. To put it simply, in both African and Irish practice, music and dance were inseparable. Some music was sung or played unaccompanied by dancing, of course, but music meant for dancing was far more common. Melodies and rhythms intertwined with steps and moves. Tunes distinguished dances in Ireland, just as rhythms differentiated them in Africa. This connection made it easier for Irish and African migrants to merge their different practices. Negro jigs were one of their products.

American jig dancing was a creole form. The word jig refers to a competitive dance in 6/8 time with Irish origins, but in early America “jig dancing” and “Negro dancing” were synonymous terms, used interchangeably to describe the dance step, a style of dancing, the “set dance” format (which combines several different tune changes and steps), and competitive dancing (regardless of the tune or step being performed). Black people who performed jigs, reels, and hornpipes in an African style were called “Negro dancers and musicians” as were white people who adopted the African-American style (or performed their jigs in blackface). The Negro dancer I’m researching is an Irish American named John Diamond, who is known for a series of challenges he danced in the 1840s against an African American jig dancer called Master Juba. These rivals danced the same dance to the same tunes.

“I could bring my banjo to the conference tomorrow,” Greg suggested, “and play you ‘John Diamond Walk Around’.” “I’ve got my bones in my purse,” added Roberta.

“That would be great,” I replied and turned to Emily, eyeing her high-heeled sandals, “and will you bring your dancing shoes?”

The musical instruments and techniques used to accompany jig dancing had European and African roots. Dancers usually performed with drummers in Africa, while pipers and fiddlers played for dancers in Ireland. But in early America, fiddles and banjos were the most common accompaniments. Fiddles played with horsehair bows (on the lap or against the chest) had European and African precursors, while banjos represented the innovative development of one or more West African instruments in the Americas. When the old tunes were played on these hybrid instruments, they made a new sound that inspired new compositions, tunes that became “American” dance music.

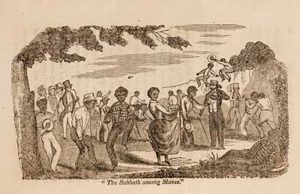

When no instruments were at hand, people used their bodies to accompany dancing. Irish dancers and musicians whistled or hummed the dance tune, a sean nós (old tradition) known as “lilting,” while African Americans beat their hands on the sides of their legs and their heel on the ground, a melodic drumming technique known as “patting juba” (fig. 1). These instruments and accompaniments were passed from one group to the other in North America. In the 1830s, a travel writer visiting Buffalo noted that “the beaten jig time” of the Irish boys dancing on the wharves “was a rapid patting on the fore thighs,” while a journalist in Philadelphia observed New Jersey slaves dancing jigs on market streets “while some darkies whistle.”

Until the 1840s, fiddles were more ubiquitous than banjos as dance accompaniment in America, and black fiddlers were by far the favorites. Bob Winans, another early-banjo player/scholar who joined our group at the “Triumph in my Song” conference, has collected hundreds of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century newspaper advertisements for slave sales and runaways that include “fiddler” in the description of the person. I’ve also found free African Americans advertising themselves as music and dancing masters. Fiddlers “able to play for dancers” needed a high proficiency, which suggests some trained with master musicians already versed in European dance music. Black fiddlers played for dancers in kitchens and barns, taverns and dance halls, circus tents and theaters. New York freeman Solomon Northup was lured into slavery by speculating kidnappers claiming they were agents hiring for a circus in the District of Columbia. Their proposal was not at all remarkable to Northup, who often played at private balls and public gatherings. These fiddlers influenced the style of all the jig dancers for whom they played.

Greg arrived at the conference the second morning toting an 1850s reproduction “minstrel banjo,” fitted with a calfskin head, four long gut strings and a short thumb string, and tuned a fourth below its modern equivalent. Banjos originated as an accompaniment for dancing among plantations slaves throughout the Americas. But it was “Negro musicians” (mostly white men in blackface) performing for itinerant circuses who spread them throughout North America. Banjo player Joel Walker Sweeney, an Irish American who cultivated his musical and dancing talents among “plantation and corn-field” slaves in Virginia, traveled with Rufus Welsh’s equestrian circus in the 1830s. Landing in dozens of towns and cities across the states and provinces, these travelers passed on and carried away local styles and skills developed wherever whites and blacks worked or lived in close proximity.

To recreate the tenor and flavor of the music that early Americans danced to, Greg uses a down-stroke technique (called Negro style in the 1850s and frailing or clawhammer style today). Fiddles and banjos are melodic instruments, but the way they were played could accentuate a dance tune’s rhythms. And like fiddles, early banjos have fretless necks, which means musicians playing either instrument could easily add the accents and slurs that give Irish dance tunes their enticing lift and African-American music its tantalizing swing.

In early America, good musicians did not just keep time for the dancer; they responded to the steps, inserting rhythmic and melodic passages of their own. Nor did good dancers just follow the music; they embellished it with their rhythms; they played a duet with the musician. That’s certainly what Emily did when Greg sat down to play for me that afternoon.

As Greg thumbed and stroked the strings and walked his fingers effortlessly across the banjo’s neck, Emily caught the melody and started to jig! She danced in sneakers, but you could still hear the beats of her steps, which Roberta amplified with the clacking of the bones. Emily shuffled and hopped and kicked from the knee, crossed her shin with her foot, jumped forward and skipped back, and swung her feet from side to side. Then the melody turned, as Greg danced his fingers up the scale and down in a clever passage, but Emily followed him up the floor, stepping and twisting her feet along with the notes. They laughed then, and caught each other’s eye, and Emily bounded with both feet into the air, landed on one foot, and brought the other down with a stamp that perfectly matched the end of the tune.

Irish dancers choreographed black moves into their steps, just as black musicians transposed Irish tunes to fit their playing styles. But the transfer of culture was a little more complex than that, since dancers also translated melodies and rhythms into movements, and musicians translated movement into music.

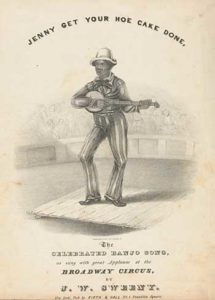

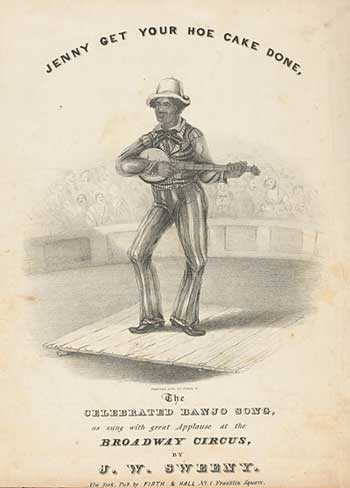

I don’t think Greg is a dancer. But because musicians often were in the nineteenth century, he’s trying to learn. On the cover of an 1840 song sheet for “Jenny get your hoe cake done,” Joel Sweeney is depicted in “Negro” costume strumming his banjo on a wooden ballast inside a circus ring (fig. 2). The soundboard (elevated by strips of wood) on which he stands and his high-heeled boots suggest Sweeney accompanied his singing and playing with acoustic dance steps, probably hornpipes. (Hornpipe dancers in Ireland sometimes danced on a wooden door taken off its hinges and laid on the floor.) “Hornpipe” was the name given to any solo dance in 2/4 or 4/4 time in which the percussive accompaniment of the dancer’s feet to the music was the main feature. For a musician like Sweeney, however, hornpipes were a form of music-making.

Dancers were also musicians. The prize awarded at a grand “Dancing Match” in Germantown, Pennsylvania, on a Saturday night in October 1858, was a “Violin, valued at $100,” indicating a contemporary expectation that competitive dancers could play music. The match was danced to tunes in “regular jig time. Mr. George Schaeffer being chosen as ‘Fiddler.’ At 8 o’clock, George struck up, and Frederick [Axe] simultaneously made his appearance—5 to 4 was offered on him and taken. His dancing was done ‘very agreeable.'” But Israel Huff, the dancer who “fairly won the prize,” was obviously a musician, for he “stepped into the arena and made his ‘Virginny’ steps tell a musical tale.”

Methods for making music with the feet were shared by white and black dancers. On plantations in Kentucky, recalled ex-slave Robert Anderson, “we danced some of the dances the white folks danced, … but we liked better the dances of our own particular race.” These dances were “individual dances, consisting of shuffling of the feet, and swinging of the arms and shoulders in a peculiar rhythm of time [which] developed into what is known today as the Double Shuffle, Heel and Toe, Buck and Wing, Juba, etc. The slaves became proficient in such dances, and could play a tune with their feet, dancing largely to an inward music, a music that was felt, but not heard.” White dancers added the slaves’ sound steps to their jigs, and black dancers adopted the Irish custom of dancing on a wooden board to enhance the sound of their jigs.

Emily uses Constance Valis Hill’s term “orality of the feet” to describe these sound steps and techniques. In traditional Irish step dance, the tune (or figure) changes kept the dancers on their heels and toes, shifting from one rhythm to another. The most common dance tunes—jigs in 6/8 time, reels in 4/4 time, and hornpipes in 2/4 or 4/4 time—share a duple downbeat but have syncopated internal beats. Irish and African American percussive dancers combined and connected these rhythms, speeding them up, battering the boards, slowing them down, scraping the ground, and crossing them over with rippling taps that hit just outside the beat. Emily also swings her arms and sways her torso like Anderson did, making visual music that emanates from inside her body.

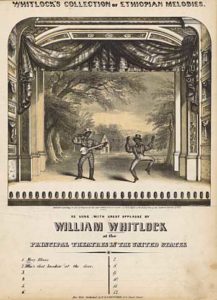

Not everyone could dance their music like Sweeney and Anderson, but dancers preferred musicians who knew some steps and musicians liked working with dancers who could play a tune. Jig dancers at matches sometimes brought their own violin or banjo player with them, since great dancing often depended on the musician’s ability to recognize and anticipate the dancer’s moves and steps. You can see this synergy in an 1846 drawing of banjo player William Whitlock and jig dancer John Diamond performing at a theater in New York (fig. 3). Diamond is in the middle of a “tailor’s leap,” a dynamic step in which the dancer “flings the right heel up to the ham, up again the left,” then lands and continues his steps without missing a beat. Whitlock’s hand is poised in the air, his eyes fixed on Diamond’s feet, preparing to strike the strings at the exact moment the dancer lands. Clean entrances and exits demonstrated the musical proficiency of both performers.

Some tunes were named after the musician who composed them, others for the dancer whose steps made them famous. Emily danced to “Briggs’ Jig,” named after Tom Briggs (stage name T. Fluter), a banjo player who accompanied Master Juba and John Diamond. Diamond’s signature step was “Camp Town Hornpipe,” named for Philadelphia’s Camp Town, an integrated suburb on the Delaware River (fig. 4). “John Diamond Walk Around” is not the same tune, despite the fact that American dancers often called their competitive hornpipes “Walk Arounds” (for their initial step) or “Camp Towns” (after Diamond’s dance).

The titles of tunes communicated particular rhythms, steps, and styles to musicians and dancers. Irish writer Patrick Kennedy depended on that knowledge when he described the exhibition hornpipe dancing he saw in County Wexford around 1818. First, the dancer

circumnavigated’ the floor twice, in opposite directions, and then with arms crossed, or poised, or whirled as he pleased he went through his stock performances, of which we give some of the names—triple hornpipes being slower in movement than the double, and those again slower than the single.

Single.—’The Leg of Muton,’ ‘Kate and Davy,’ ‘Garran Bui.’

Double.—’Planxty Carroll,’ …’Tatter Jack Walsh,’ ‘Haste to the Wedding,’ … ‘Unfortunate Rake,’ ‘Paddy O’Carroll.’

Triple.—’Flowers of Edinboro,’ … ‘Spencer’s Hornpipe,’ and ‘First of May.'”

The dancer walked around the floor to signal that what came next was his or her champion steps, and Kennedy named the tunes to give the reader a sense of the dancing. But as soon as the musician started up, the company would have known what to expect. The same was true of dancers in a Philadelphia tavern in 1848. When the black “fiddler strikes up ‘Cooney in de holler,'” noted urban writer George Foster, “the company immediately ‘cavorts to places.'” For this mixed crowd the tune and its name meant their favorite kind of jig dancing.

The close association between music and dance created a friendly rivalry between dancers and musicians, which could be heard in the increased tempo and intricate patterns of their embellishments. These contests were sometimes played out on the dance floor. At balls held on Saturday nights in a rented room at Tammany Hall in the 1840s, the couple left standing at the end of the sets challenged the fiddler to a duel to see who could hold out the longest.

It was muscle and sinew against horsehair and catgut. For a few minutes the race is as even as that of two steamers on the Hudson; but soon the elbow-power of the principal fiddler begins to relax—his tones come forth more and more feeble, and his tortured instrument gives a piercing and unearthly scream every time it comes to ‘the turn of the tune.’ Meanwhile upon the floor the fun grows ‘fast and furious’—the spectators applaud, the dancers redouble their exertions, their faces glowing like … lovers caught kissing. At last the despairing fiddler claps his left thumb and forefinger to the nut of his E string—snap! pop! It is gone—the dance is finished and he saves his reputation.

The lived experience of doing what you research, or at least fraternizing with people who do, can give you insight you can’t get pouring over the sources. Seeing Emily dance to Greg’s music was like finding a long-lost picture of these dancers and musicians, only better, because I could hear them and see them moving. I have to admit, tears welled up in my eyes, because that was it, that was why black and Irish musicians and dancers came together, because together they made something new and exciting, something the whole company enjoyed. I couldn’t help myself; I yelled out, just like the people in my documents: “Whoo Emily! That’s the girl; handle your feet, avoorneen! That’s it, Greg! Finger those notes; what a tune! You’re one of ’em!”

The interdependence of good dancing and good musicianship is captured in old sayings like “pay the piper” and “face the music.” In rural Ireland, old and young for miles around met at an alehouse or other “public place of resort” to compete in jig dancing contests, called “cakes” for the prize awarded the winner (as in “she takes the cake”). “At the end of every jig, the piper is paid by the young man who danced it, and who [enhanced] the value of the gift by first bestowing it on his fair partner, and a penny a jig is esteemed very good pay, yet the gallantry or ostentation of the contributor anxious at once to appear generous in the eyes of his mistress, or to outstep the liberality of his rivals, sometimes trebles the sum which the piper usually receives.”

This Irish tradition made playing for jig dancers good employment for African American musicians. In 1848, a reporter for the New York Tribune visited a groggery hotel in Philadelphia’s Southwark district where working-class men and women came to drink and dance. When the “old negro fiddler” strikes up a tune in a dancing-room upstairs, he says:

The dance proceeds for a few minutes in tolerable order; but soon the excitement grows, the dancers begin … accelerating their movements, accompanied with shouts of laughter, yells of encouragement and applause, … Affairs are now at their height. The black fiddler increases the momentum of his elbow and calls out the figure in convulsive efforts to be heard [while] the dancers, now wild with excitement, leap frantically about … and at length conclude the dance in the wildest disorder and confusion. As soon as the parties recover, the fiddler makes his appearance among them and receives from each gentleman a tip as his proportion of the ceremony of ‘facing the music,’ and the floor is cleared for a new set; and so goes on the night.

For black fiddlers and white dancers, adopting another group’s cultural practices did not have to mean oppression or loss. Negro jigs were the property of both. They represented the repositioning of old loyalties, the acceptance of new partners, and even at times increased affluence.

My paper was scheduled on the last morning of the conference. Our crew and a few other scholars who’d joined us along the way were in attendance. I’m no expert at performing Negro jigs, but I always dance a couple of moves to illustrate the difference between Irish and African style, play recordings of fiddle and drum music so people can hear twos crossing threes, and if I’m feeling brave, put on some banjo music and show them the “time step,” which combines these elements. It’s a little embarrassing since I’m never sure historians comprehend why I’m doing it. But Greg and Emily certainly did. So I asked them to perform for the people who came to hear my paper. And it was amazing. Their music and dance expertise enhanced the quality of my work. They clarified what I was saying about black-Irish exchange and Negro jigs, and that wasn’t all. They also demonstrated how the possibilities for understanding something as ephemeral as the past increase when unlike practices are given chances of communication. Musicians and dancers, historians and performers, minds and bodies, we all became partners in time.

Greg Adams and Emily Oleson, “Briggs Jig” (Briggs’ Banjo Instructor, 1855), filmed June 1, 2012.

Further reading

Scholars have gone far in uncovering the origins of African American dance. Recent works include African Dance: An Artistic, Historical and Philosophical Inquiry, ed. Kariamu Welsh Asante (Asmara, Eritrea, 1998); Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance (Urbana, 1996); Marshall and Jean Stearns, Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (Da Capo, 1994); and Lynn Fauley Emery, Black Dance From 1619 to Today (Princeton, 1988). Unfortunately, we are far less familiar with the origins and influence of Irish American dance. Useful works include Close to the Floor: Irish Dance from the Booreen to Broadway, ed. Mick Moloney, J’aime Morrison, and Colin Quigley (Madison, Wis., 2008); Mary Friel, Dancing as a Social Pastime in the south-east of Ireland, 1800-1897 (Dublin, 2004); Helen Brennan, The Story of Irish Dance (Lanham, Maryland, 2001); Brendan Breathnach, Folk Music and Dances of Ireland (London, 1996).

Recent scholarship on creolization and cultural exchange among African and Irish Americans includes Christopher J. Smith, “Blacks and Irish on the Riverine Frontiers: The Roots of American Popular Music,” Southern Cultures (Spring 2011): 75-102; Constance Valis Hill, Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History (Oxford, 2010); Robin Cohen, “Creolization and Cultural Globalization: The Soft Sounds of Fugitive Power,” Globalizations 4: 3 (September, 2001): 369-384; James W. Cook, “Dancing Across the Color Line,” Common-place (October, 2003); Shane White, “The Death of James Johnson,” American Quarterly 51:4 (December 1999); W. T. Lhamon Jr., Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (Cambridge, 1998); Ira Berlin, “From Creole to African: Atlantic Creoles and the Origins of African-American Society in Mainland North America,” William and Mary Quarterly 53 (April 1996): 251-28; John F. Szwed and Morton Marks, “The Afro-American Transformation of European Set Dances and Dance Suites,” Dance Research Journal 20:1 (Summer 1988): 29-36; Greg C. Adams, “19th-Century Banjos in the 21st-Century: Custom and Tradition in a Modern Early Banjo Revival” (MA thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, 2012); and my forthcoming piece, “The Challenge Dance: Black-Irish Exchange in Antebellum America,” Cultures in Motion, ed. Daniel T. Rogers (Princeton, 2013).

Primary sources for this article include George G. Foster, “Philadelphia in Slices,” New York Tribune, Nov. 17, 1848 and New York in Slices (New York, 1849); Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave (1853); “Dancing Match,” New York Clipper, Oct. 31, 1857; Robert Anderson, From Slavery to Affluence, Memoirs of Robert Anderson, Ex-Slave, ed. Daisy Anderson (Steamboat Springs, Colo., 1927); and “The Cake Dance,” Béaloideas: The Journal of the Folklore of Ireland Society XI.1-11 (1941): 126-142.

On using dance as a primary document for teaching and researching history see April F. Masten, “Dancing Through American History,” Common-place (October 2005).

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

April Masten is associate professor of history at Stony Brook University. She is author of Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in Mid-Nineteenth Century New York (2008).