Phillis Wheatley’s Pleasures: Reading good feeling in Phillis Wheatley’s Poems and letters

There was a time when I thought that African-American literature did not exist before Frederick Douglass. Then, in an introductory African-American literature course as a domestic exchange student at Spelman College, I read several poems from Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). I confess I had no idea who she was before I read her name, poetry, or looked on the frontispiece of the collection. Over the course of our classroom discussion, I learned that she was an enslaved (later freed) young woman and the first black person to publish a book of poetry in America.

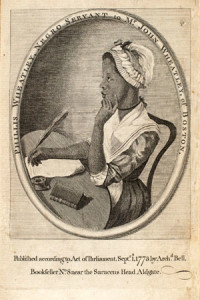

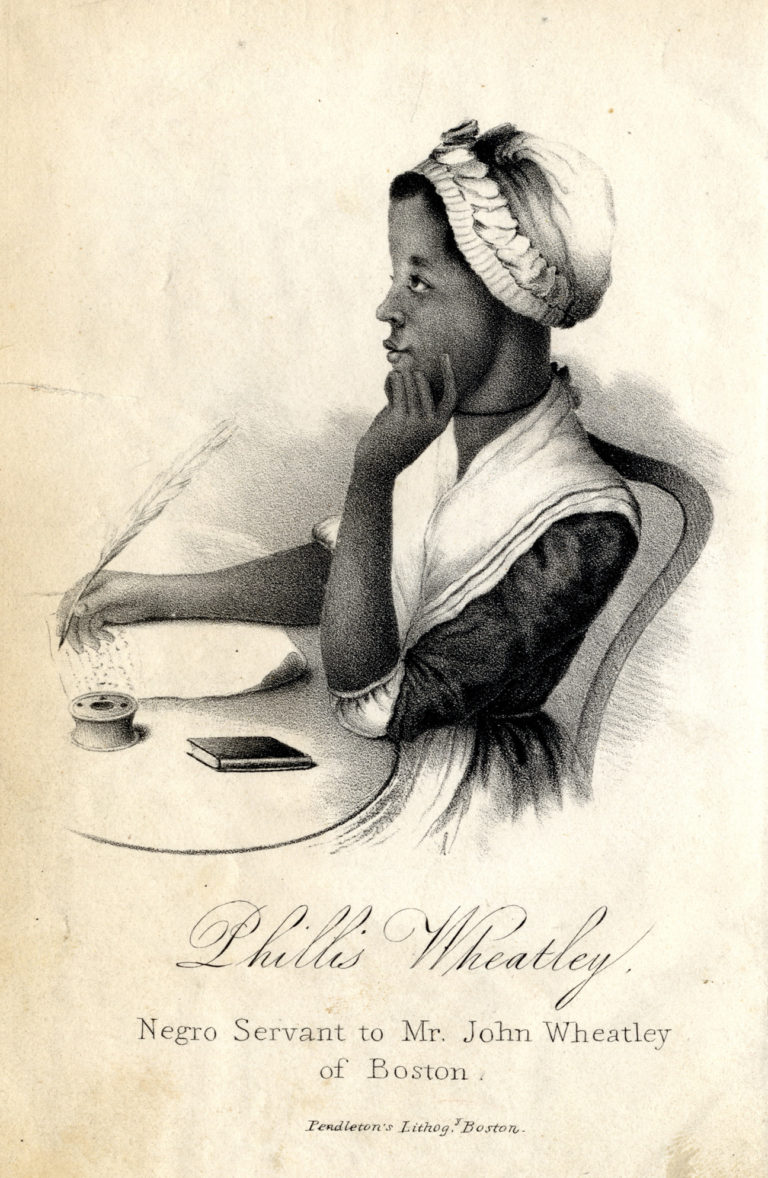

Even after learning this brief history, I paid very little attention to the poems themselves because I was far more concerned with the frontispiece. On the front cover of my Penguin edition, there appeared the body of Wheatley. Because she was, in fact, a black woman, her body confirmed her place as the “inaugural poet” of African-American literature. I stared at the engraved image of a thoughtful young African woman with pen in hand, bounded by the words, “Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston.” I read the words again only to return to her body. Because I could see her—the complexion of her etched skin, her pensive gaze, her fingers bent slightly around her quill pen, her body poised and seated at a desk—she was not simply the words that meandered around her engraved image. She was real.

More than the words of the prefatory testimonials, the biographic information, or even the presence of her poetry, the frontispiece made Wheatley real to me. Despite her master John Wheatley’s account of young Phillis’ life and the preface’s obligatory mention of her intention in writing—”[t]he following Poems were written originally for the Amusement of the Author, as they were products of her leisure Moments. She had no intention ever to have them published…”—I imagined her as she was pictured there: a servant fixed in time, sequestered and forced to write even though her master’s prefatory comments suggest that she, while enslaved, had moments of leisure.

Out of this picture, I constructed a story. It began in Africa with her declaration, “‘[t]was mercy brought me from my Pagan land/Taught my benighted soul to understand/That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too.” It continued through the infamous Middle Passage that brought her to America (though an explicit reference to this fact is absent from Wheatley’s writing) and into Boston where a precocious young woman fought against her oppression by writing verses—like, “Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain/May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train”—with a subtle irony that masked her resistance. My story ended with a celebration of a new literary tradition, African-American literature. This story was a memorial to a past that I presumed was dependent upon the emergence of texts that represented the suffering and resistance of a racial body (just like one that appears in the frontispiece of Wheatley’s poems).

This is a satisfactory story if we are to assume that race is Wheatley’s ultimate concern; that literary traditions emerge from a single point of origin (a collective racial identity, in this case); that such traditions are linear and therefore move seamlessly from one author to the next (for example, Phillis Wheatley gives rise to Frederick Douglass and then to Langston Hughes and on to Toni Morrison). Its simple narrative mobilizes a history, which understands race as a collective way of behaving that is loosely tied to a collective history of suffering. It is a story where the idea of race emerges out of a belief that privileges great suffering (for example, the physical privations of slavery) and ties it to “real” accounts of the “African-American experience” or “authentic” ways of behaving and acting black. Wheatley’s suffering inaugurates this literary tradition, this collective way of behaving, which is later marked by stories of suffering or resistance and heroic accounts of overcoming (see of course Frederick Douglass).

The assumptions that foreground this story are right in part. It is certainly the case that Wheatley is important to the history of African-American literature. Just as it seems plausible that Wheatley resisted her adverse circumstances, it also seems true that Wheatley experienced suffering, as evidenced by her testimonial:

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?…

Such, such was my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway.

In this poem “To the Earl of Dartmouth,” Wheatley offers her readers a reconstructed memory—one of the few that appears in her poetry—that recalls her loss and her father’s suffering. Wheatley turns this memory into a “teachable moment,” by professing the origins of her desire for freedom; she recalls the “cruel fate” that snatched her from Africa and a past she no longer remembers. Wheatley, by way of her suffering, seeks to garner the attention of her audience to create a sympathetic connection with them.

But this story is too simple and ignores an obvious fact. Though marked by the racialized words (“African,” “Black,” or “Negro”) of the title page, eighteenth-century African-American authors rarely discuss what it means to be part of a cohesive racialized community. Moreover, when what could be classified as racial subjectivity—namely, an identification with those racial markers—appears in this literature, it is not tied solely to a collective bodily suffering.

Let’s consider for example the case of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African prince, former slave and friend of the Huntingdon Methodist Connection, the religious network of the Countess of Huntingdon Selina Hastings that included famed itinerant minister George Whitefield, Phillis Wheatley and several other notable anglophone black writers, such as the multifaceted Olaudah Equiano, and minister John Marrant. In his A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, An African Prince, Written by Himself (1774), Gronniosaw, after observing his master read, mimes the action he sees. But what he sees is not the practice of reading but rather the book talking directly to his master. He explains,

I open’d [the book] …in great hope that it would say something to me; but was very sorry and greatly disappointed when I found it would not speak, this thought immediately presented itself to me, that every body and every thing despised me because I was Black.

Gronniosaw sees his blackness for the first time because he is unable to hear the religious text (a prayer book) that he hopes would speak to him.

Though this failed dialogue might be read as a part of a racialized moment of becoming, he is not speaking of an embodied racial identity. What Gronniosaw actually does is admit to his sinfulness (albeit problematically tied to the word “black”) in a manner similar to St. John in Revelations 5 who writes of a book that is to be opened and read by those who are worthy. The worthy are called forth yet “no man was found worthy to open and to read the book, neither to look thereon” (Rev. 5:4). Because Gronniosaw is a sinner like the unworthy of St. John’s story, he is unable to access the Word and to hear it as true believers can and do. Gronniosaw uses this encounter with the book, quite often referred to as the “talking book,” to criticize those who do not have a proper relationship with the Word of God. This “talking book” event appears with revision repeatedly in early African-American literature in the narratives of John Marrant, Olaudah Equiano, and John Jea. Much of the critical discussion of this scene focuses on the act of reading and by implication the desire to read even though in each version, a verbal conversation is expected between the book and “reader.” The result of this overemphasis on book reading and learning is a neglect of the religious intention of the author—to talk to and hear the Word of God.

As in the case of Gronniosaw, Wheatley does not write about race as a collective and embodied experience. As my fellow students observed in that introductory African-American literature course, Wheatley’s poetry mimes the poetic forms of dead white men like Alexander Pope and John Milton. Because her poetry lacks a historical sense of race that is fixed across time and geography, my peers argued that her mimicry of these men confirms that she was not “black” enough to be considered culturally important. When they searched for some reference to an acute desire for freedom from enslavement (the marker of authentic, enslaved black identity) as in the case of Frederick Douglass, they came up short. Wheatley does not narrate her plan to escape to freedom even though she does admit to a desire for freedom in both her poem, “To the Earl of Dartmouth” and in her letter to Samson Occom. Instead, she celebrates her enslavement because of the distance it creates between the “benighted” country of her birth and the redemptive nature of her American present (see “On Being Brought from Africa to America”).

Phillis Wheatley participates in and documents “something else,” as Ralph Ellison writes, “something subjective, willful and complexly and compellingly human.” When Ellison speaks of this “something else” in his essay, A Very Stern Discipline, he attempts to counter the literary emphases upon the “real,” the grit, the suffering of black life. Though he is unable to name this “something else,” Ellison admits there is a complexity that contrasts or exists alongside the simple sociological realities of twentieth-century black living, marked by the existence of suffering and that which he describes as “ruggedness,” “hardship,” and “poverty.” Ellison does not aim to say that the human (or in particular African-American) experience is without suffering. Rather, his choice of phrasing, “something else,” names an alternate possibility—in this case the possibility that Phillis Wheatley’s historical value is not tied to her raced body. Moreover, tradition-making is not her sole legacy. It begs the questions: How do we, at present, understand Phillis Wheatley if she is not to be remembered as a “first”? Who is Phillis Wheatley if her racial body—as it appears thoughtfully and writerly in the frontispiece—is not her single-minded concern?

What follows is my interrogation of these questions in Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral and letters. Though she is often touted as the first to jump-start the African-American literary tradition, Wheatley’s poetry actually confronts the limits of this idea because it lacks an interest in a racialized subjectivity. Her poems challenge the story that privileges her racial body and the scholarly expectation that race should operate as a governing principle in African-American literature. Her position as “first” is irrelevant when her writing is placed within the many communities that she wrote for, communities that included enslaved, Christian, Methodist, English, or free African populations. Wheatley inhabited multiple “writing communities,” to borrow a term coined by literary scholar Katherine Clay Bassard. Wheatley’s eighteenth-century writing communities created an imagined space, much like the cyberspace of today’s e-mails, text messages and Facebook, within which invention and conversation were possible. Such communities are structured by the bonds created through written exchange. Within the space of these written communities, networks are formed; ideas are discussed and traded; friends can talk amongst themselves. These networks are not based upon bodies or even experienced through bodies but instead by way of the words on the page or in a letter or a poem.

The result is what Bassard describes as a “rhetorical meeting place”—the site of these imaginary conversations—wherein Wheatley converses in writing with those who allow her to create and invent a self. There, she lays claim to the processes of renegotiation and revision out of which her intertextual communities emerge. Put differently, she is the author of this space. She not only writes poems and letters but also crafts an ideal self that is not bound to or by her body. At the site of this “rhetorical meeting place,” there is a body that does not matter. Therefore, it is not a necessary antecedent to the development of African-American literature. There is also textual revision and dialogue. Words, phrases, passages lifted out of other texts, particularly the Bible, enter into conversation and merge into her writing. The result is not mimicry but rather marks the boundaries of this writerly space and exchange.

No longer bound to a black body, an explicitly African body in this writing space, there is “something else” that matters more to Wheatley. It is her Christian faith. Wheatley uses her faith to counter the limits of her body: its flaws (“some view our sable race with scornful eye,/ Their colour is a diabolic die;”) its tendency towards sin and earthly pleasures (“Let us be mindful of our high calling, continually on our guard, lest our treacherous hearts/Should give our adversary an advantage over us”); and its sickliness (namely, asthma and consumption). The language of Christianity offers Wheatley a way to imagine a self that transcends the fleshly weakness of her body. This transcendence is not out of the body. Instead, it takes places inwardly. There, in the interior space of her heart, Wheatley experiences a transformation each time she opens this self to God. When she speaks of God and praises his name, Wheatley accepts the indwelling Spirit and admits to her desire to converse and fellowship with God. For Wheatley, desire is a religious imperative through which she is called to conversion, and subsequently, faith. The satisfying result of this desire is a pleasure—marked by her repeated use of the words “joy,” “enrapture,” “passion,” and “happy” that releases her completely from the confines of her body into a union with God.

In a July 19 1772 letter to her friend and fellow slave Obour Tanner, Wheatley speaks of the “poor state of health” that has claimed her body throughout much of the winter and spring. She asks Tanner to pray for her and offers the following prayer for herself,

While my outward man languishes under weakness and pa[in], may the inward be refresh’d and Strengthened more abundantly by him who declar’d from heaven that his strength was made perfect in weakness!

Wheatley calls upon Tanner to pray with and for her weak body. With Tanner, she enters into a rhetorical meeting place that begins a dialogue of fellowship with a friend that gives her body the strength to call upon God. By way of this prayer, Wheatley makes possible a mutual exchange between herself and God. When writing and speaking of God, Wheatley becomes present with God; there, she admits to her weakness and ties it to not only the pains of her illness but also to the “outward man” that is bound by the fallibility of the flesh.

Though Wheatley’s body languishes in pain and weakness, her prayer is not directed toward her flesh. Instead, Wheatley juxtaposes her weak and sickly body against an unnamed inward self, a self that can enter into dialogue with God, Tanner, and an imagined fellowship. Revising the language from St. Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians, Wheatley calls attention to the ways in which this unnamed inward self might be strengthened—namely by receiving the Spirit (that which is eternal) inwardly through her senses of touch, smell and sight. She invokes 2 Corinthians 4:16 where Paul writes, “but though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day.” Wheatley’s declaration, “his strength was made perfect in weakness,” borrows the wording of 2 Corinthians 12:9 and anticipates Paul’s charge to “take pleasure in infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses for Christ’s sake: for when I am weak, I am strong.” Wheatley strategically selects these passages for revision because they offer her a framework within which to strengthen this inward self that is renewed by the weakness of the flesh. That is to say, her personhood, or as she describes it her “outward man,” no longer matters because there is this interiority, this inward self with whom she can feel strengthened by God.

When Wheatley speaks of this inward self, she describes a space that is created by what she calls the “saving change”—that is, religious conversion. The “saving change” names the change of heart that occurs at the site of this inward self. This interiority possesses the open heart required to welcome the Holy Spirit. It is what Wheatley speaks of when she writes to John Thornton on December 1, 1773:

Therefor disdain not to be called the Father of Humble Africans and Indians; though despis’d on earth on account of our color, we have this Consolation, if he enables us to deserve it. ‘That God dwells in a humble & contrite heart.’

Once again, Wheatley views her outward man (African and “despis’d on earth on account of [its] color”) as weak, the opposite of the “humble & contrite heart” wherein God dwells. Despite the weakness implied by her skin color, she remains confident in the quality of her inward self. Therefore, she aligns her inward self with those who deserve God’s consolation—namely, the heart that is properly opened to receive his Spirit.

Her open heart appears again when she writes to Tanner, “[h]appy were it for us if we could arrive to that evangelical Repentance, and the true holiness of heart which you mention.” What she celebrates in this exchange is the “saving change” which produces the true holiness of heart. She understands that it is a fleeting sentiment that must be cultivated properly. Her attention to this interior and her allusion to its proper cultivation recall the words of Whitefield, who in his sermon The Indwelling of the Spirit, Common Privilege to all Believers, begs the question—”[b]ut unless Men have Eyes which see not, and Ears which hear not, how can they read the latter Part of the Text, and not confess the Holy Spirit, in another Sense, which is the common Privilege of all Believers, even to the End of the World?”

When Whitefield poses this question, he enjoins his reader or audience to make way to receive the Word of God into his heart. Though eyes and ears are often attached to bodies, what he describes is not a body but rather an ability to sense, namely hear and see, properly. It is what Wheatley imagines in her poem “Thoughts on the Works of Providence,” when she writes, “Arise, my soul, upon enraptured wings arise/To praise the monarch of the earth and skies.” So enthused, she leaves her body in order to take up with her soul. Because her soul knows no bounds, it rises “upon enraptured wings” and celebrates God by hearing and seeing the works of providence. The world, through which her soul soars, is rife with wondrous sights—”morning glows with rosy charms”—and sounds—of “the winds and surging tides.” If the believer possesses the proper feelings (seeing eyes and hearing ears), she can then claim that she is a Christian who, as Whitefield explains, “in the proper Sense of the Word, must be an Enthusiast—That is, must be inspired of God, or have God in him.” Whitefield offers a charge—the Christian “must be inspired of God, or have God in him”—and enjoins his listeners to welcome the Spirit inwardly; the result, of course, of this inward dwelling of the Spirit, is a “new birth.”

As a faithful follower, Wheatley experiences this “new birth.” In his sermon The Marks of the New Birth, Whitefield outlines the ways in which an individual can recognize this inward regeneration. There are five “scripture marks”—praying and supplicating, not committing sin, conquest over the world, loving one another, and loving one’s enemies—that not only identify the conversion experience but also acknowledge the inward presence of the Holy Spirit. This birthing process can only occur when an individual accepts God inwardly. Whereas Whitefield emphasizes the importance of these acts (to pray, to commit no sin, to love), Wheatley identifies the feelings that result from these acts. She goes one step further and admits to the conversation that must occur between her inward self and God in order to feel so deeply. Thus Wheatley, reborn in spirit, rids herself of the limitations of her outward body. She nurtures the interiority wherein she feels the pleasure inspired by the presence of the Spirit. This pleasure confirms that Wheatley is one of the “[f]ollowers [who] might be united to him [God] by his Holy Spirit, by as real, vital, and mystical an Union as there is between Jesus Christand the Father.”

In an October 30, 1773, letter to Tanner, Wheatley imagines this union: “Your Reflections on the sufferings of the Son of God, & the inestimable price of our immortal Souls, Plainly dem[on]strate the sensations of a Soul united to Jesus.” Though it is uncertain what Tanner has said in her letter, Wheatley’s response commends Tanner’s union to Christ. When she speaks of these sensations, she alludes to the sensory, the inward, means by which this union manifests itself. The soul united to Jesus is one that has experienced the “new birth” and has established the religious dialogue between the inward self and God. It understands “[w]hat a blessed Source of consolation that our greatest friend is an immortal God whose friendship is invariable!”

Wheatley examines the invariability of God’s friendship in a curious confrontation between the allegorical figures, the immortal Love (see 1 John 4:8) and Reason, in her poem, “Thoughts on the Works of Providence.” The confrontation begins with a question from Love to Reason: “Say, mighty pow’r, how long shall strife prevail/And with its murmurs load the whisp’ring gale?.” Love, imagined as God, berates Reason, the mortal voice, for her failure to recognize Love’s divinity and her creative power. Love demands that Reason remember her power to regenerate and share herself with every thing: “Refer the cause to Recollection’s shrine,/Who loud proclaims my origin divine,/The cause whence heav’n and earth began to be,/And is not man immortaliz’d by me?” These questions articulate a desire to reunite with Reason to transcend the strife between Love and Reason. By asking her to remember God, Love persuades Reason to reinstate this “invariable” friendship. Reason is not concerned with her body and its union with God; instead, Reason speaks of her feeling and the means by which this feeling enthuses her inwardly. What results from this reunion is that Reason is “enraptur’d.” She feels the “Resistless beauty which thy [Love’s] smile reveals.” Reason feels this beauty because she can speak again to God; this allegorical conversation—this dialogue of feeling and this communal exchange—pantomimes the means by which the Spirit dwells inwardly.

Reason is changed yet again with the return of Love not only by this conversation but also the embrace that finalizes their confrontation. Reason’s words are “ardent” when she speaks and she burns at the charms of Love when she finally “clasp’d the blooming goddess in her arms.” The burn that Wheatley imagines in this exchange is both pleasurable and inspired by a conversion that takes place. When Reason “clasp’d” Love, she accepts Love inwardly and feels her as this burning desire. Together, they share their thoughts on the works of Love’s providence, which are heard as “Nature’s constant voice” and seen as the sun rises and the “eve rejoices.” This imagined conversation mimes the process of inward regeneration that results from the “new birth.” Wheatley imagines the inward self as it is transformed and reborn in Love and Reason. She captures the ways in which both converse in order to share deeply the experiences of the other. What she documents is an emergent community that not only represents an important textual moment but also her relationship to Tanner and the larger writing communities of which she is a part. Wheatley proffers a religious literacy wherein a true believer—one who possesses an open heart where Love and Reason coexist—can receive the Spirit and, subsequently, speak of the pleasure of this union.

Thus, what Wheatley documents in this exchange and, more generally, in her letters, is the journey of the inward self, united to God by a sincere faith. She makes clear that cultivation of a proper inner life is critically important to the experience of a good Christian. Her fellowship with Tanner, Thornton, Whitefield and others memorializes the actualization of her desire to converse with God and to experience the pleasure of this exchange. Her real and poetic descriptions of this relationship offer her readers a sense of her interior life—a life that supersedes a concern for her race. So strengthened, Wheatley divorces her weak fleshly body from the experiences of this inward self who delights in and is transformed by way of sharing deeply with God. Wheatley not only shares deeply with God but also makes her inward self, her interiority, accessible to a community of readers with whom she marks the site of those feelings (joy and pleasure) that result from her satisfied desire to praise God within a fellowship of believers. Wheatley leaves a legacy in print of this inward change that transforms her self and the way that we, as readers, remember her.

I wrote the earliest version of this essay as a response to my undergraduate students’ disdain for early African-American literature. After reading selections from Wheatley and Olaudah Equiano’s Narrative, my students were surprised and disappointed by what they described as complacency. They repeatedly questioned Equiano’s desire to readily accept his enslavement, and criticized his (mis)representation of a slave’s experience. Without the obvious brutality and violence that they had observed in Douglass’ Narrative and the Roots mini-series, Equiano represented an eighteenth-century “sellout,” a prototype for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom whose lack of resistance stripped him of the African identity that marks the full title of his narrative. It was clear that what my students wanted and expected to read were autobiographical accounts of the “real black history;” here, “real” invokes the modern-day colloquialism, “keeping it real.” To “keep it real” signifies the cultural practices, the ways of behaving, the performance of blackness that have come to inform my students’ understanding of race. Though they acknowledged that race is socially constructed, what they wanted was writing that “keeps it real”—that is, racially authentic, really “black.” Put differently, my students wanted texts which reinforced the misinformed idea, criticized by Ellison long ago, that “unrelieved suffering is the only ‘real’ Negro experience.” As the comedian Dave Chappelle observes in his comic skits, titled “When Keeping it Real Goes Wrong,”—that poke fun at the lives of men and women who decide to “keep it real” and suffer tragic consequences—keeping it real can and does often go wrong.

As I recalled their emphases on the “real black history” and subsequent criticisms of Equiano, Wheatley, and their contemporaries, I realized that the present essay is not merely a response to my students. It is not simply a nostalgic account of my earliest encounters with early African-American literature. Rather it is story about reading itself. For this reason, it begins with a misreading, an expectation that Phillis Wheatley and her literary successors must and will conform to my expectations for her legacy. Whereas my current students assume that Equiano and Wheatley are “sell-outs,” I, while in college, imagined a version of Wheatley that lived up to what I understood to be her legacy. Just like my students, I believed that her legacy was the very idea of black identity.

What a reconsideration of Wheatley reveals, as this story continues, is the extent to which she offers us (as her readers) a way to read her writing and imagine her legacy. Reading, in this instance, is not tied to an ability to pronounce sounds and identify letters and words. Rather, Wheatley asks her readers to adopt the religious literacy that makes salvation possible. It is inward transformation, a change of heart that is the result of her relationship to God. This change connects Wheatley (and as a consequence, her readers) to expansive writing and religious communities that intersect in the textual spaces of itinerant ministers, John Marrant and James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, merchant and philanthropist John Thornton, the Countess of Huntingdon and many others. Out of this textual space, she creates and participates in a “rhetorical meeting place.” There, she writes a life, a legacy, which celebrates the “saving change,” the salvation that allows her to feel the pleasures of a freedom in God. What she experiences there is a pleasure that is the result of her satisfied desire to share deeply with God. Her writing documents this dialogue and the pleasurable experiences produced as the Spirit converses with her inward self. This interiority allows Wheatley to celebrate her self just as it also allows her to praise her God.

To imagine Wheatley as a receptacle for the pleasures of faith introduces new questions into scholarly and classroom discussions on this early period. Without knowing it, of course, Wheatley seems to write against the assumptions that begin this essay. In doing so, she crafts a way of being that makes possible the very notion of pleasure in the lives of eighteenth-century black women. If her faith offers her this type of experience, it admits to the fact that there is “something else” that willingly admits to the humanity of black life. When she writes,

“…yet I hope I should willingly Submit to Servitude to be free in Christ.—But since it is thus—Let me be a Servant of Christ and that is the most perfect freedom,”

Wheatley shares with us the way she would like to be remembered—as a servant of Christ. She admits to the good feeling that accompanies this freedom to worship.

Further reading

For Phillis Wheatley’s poems, see Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) edited by Vincent Carretta (New York, 2001). For writings by black authors that are both contemporaneous with Wheatley and members of the trans-Atlantic Huntingdon Methodist Connection, see Vincent Carretta’s Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the 18th Century (Lexington, 1996). On Wheatley and the origins of a black women’s “writing community,” see Katherine Clay Bassard, Spiritual Interrogations (Princeton, 1999). Henry Louis Gates Jr. first coins the term “the talking book” in his introduction to the anthology Pioneers of the Black Atlantic: Five Slave Narratives from the Enlightenment, 1772-1815 (Washington, D.C., 1998) and Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literature (New York, 1988). For a well-articulated counter argument to Gates’s emphases on literacy and the “talking book,” see Frances Smith Foster’s article “Narrative of the Interesting Origins and (Somewhat) Surprising Developments of African-American Print Culture,” American Literary History 17.4 (Winter 2005): 714-740. See also Smith Foster’s article “Genealogies of Our Concerns, Early (African) American Print Culture, and Transcending Tough Times,” American Literary History 22.2 (Summer 2010): 368-380. For a discussion of the importance of the interiority (rather than the body) in early American literature, see Jordan Alexander Stein’s article, “Mary Rowlandson’s Hunger and the Historiography of Sexuality” American Literature 81.3 (September 2009): 469-495.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.1 (October, 2010).