Pictures of Panic: Constructing hard times in words and images

In the late spring of 1837, Edward Williams Clay put grease to stone in the Manhattan shop of H. R. Robinson, a caricaturist and publisher. Clay was inspired. His move from Philadelphia to New York City in 1835 offered him a front-row seat to one of the most dramatic events of his lifetime, a financial crisis of unprecedented proportions.

Philadelphia had long been the home of the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) and the center of the nation’s finances, but since Clay’s move to New York City, times had changed. President Andrew Jackson removed the federal government’s deposits from the B.U.S., depositing the funds in banks throughout the nation. Western land sales spurred by Indian removal and duties collected on imports generated more money than the federal government needed. Congress redistributed this surplus to the state governments, further decentralizing the nation’s finances. By the end of 1836, more than 700 banks were printing their own paper money in the United States. More than 100 of them had opened their doors for the first time just that year. Many of the new banks were located far away from the traditional ports of the Atlantic coast; their only tie to global trade existed on paper in the charters of not-yet constructed canals and railroads. To build these “internal improvements” companies raised capital by selling stocks and bonds in the nation’s largest financial market, located in lower Manhattan. Mere blocks from Clay’s desk, brokers with international connections managed the nation’s trade through a variety of commercial paper: stocks, bonds, bank notes, and bills of exchange. They sent accounts of imports, exports, debits, and credits across the Atlantic to the world’s central financial market in London where English investors were eager to earn the highest interest rates available in America. During Clay’s first two years in New York City his new neighborhood was the scene of not merely local but transnational and international economic excitement.

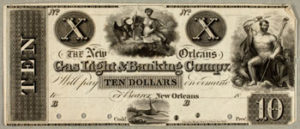

During the first few months of 1837, the times changed again. News from London arrived regarding investors’ doubts about America’s continued prosperity. British lenders raised interest rates. The confidence that had undergirded business trust evaporated. On both sides of the Atlantic, creditors demanded payment. Banks tightened up their loaning practices. Factors, brokers, and merchants failed to make payments. As one failure triggered another, the always precariously balanced system of credit collapsed. The prices of commodities, including land and slaves, plunged, pushing many to seek “safe” investments such as gold and silver coin (also known as specie). For although bank notes promised “to pay ten dollars on demand,” the banks themselves only held a small fraction of the value of their circulating paper in actual coins. Most of their assets were tied up in mortgages on property, bonds, and stocks that, like everything else, were now rapidly losing value. With anxieties rising, bank directors worried that too many holders of their notes might simultaneously demand specie. While few such bank runs had occurred by mid-May, banks throughout the nation sought to protect themselves from the possibility by preemptively suspending specie payments. This brought an end to the initial moment of panic as individuals now faced the certainty of their failure. But troubles kept mounting. Note holders and depositors, including the federal government, lost access to their assets. Foreign debtors sued their American creditors over unpaid debts. Unable to pay their workers, buy raw materials, or sell their products, factories stopped manufacturing. Unemployed workers fled cities. Farmers could not sell their produce. Creditors, sheriffs, and customs collectors seized all forms of property in lieu of debt payments. Lawsuits multiplied. Trade ground to a halt, especially in New York City, whose financial district was particularly hard hit by the crisis. Desperate speculations and miscalculations provoked a second panic in 1839 which was followed by a period of general economic depression that lasted until the early 1840s. Although this entire period would be remembered as the Panic of 1837, contemporaries only used the term “panic” to describe their anxieties during the initial months.

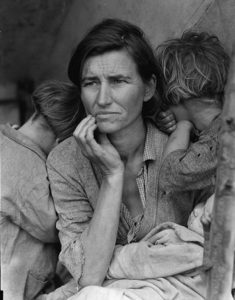

Panic inspired Clay’s art. His productivity soared after the banks suspended specie payments, a turn of events that inspired several hand-painted lithographs. One of these pictures, “The Times,” (fig. 3) staged the nation’s financial ills as if they were a theatrical production. In the foreground, the characters evoke sympathy or scorn. Shoeless tradesmen huddle beside overpriced commodities and broadsides advertising high prices for coins and credit, as well as schemes and frauds. A respectable widow and child, dressed in neat mourning black, beg for a hand out from a fat mortgage holder. A dark-skinned soldier, stogie in his mouth, watches a drunk pass a bottle of gin to a young mother lying barefoot and spread-eagle on the dirty straw floor of a lean-to. The troubles of a commercial community in crisis fill the background. Crowds throng the liquor store, pawnbroker’s shop, sheriff’s office, and almshouse. Attorneys wait on clients emerging from luxurious carriages. Clerks sit idly by the Customs House windows above a sign demanding specie for payment of duties as ships (and their cargoes) rot in the harbor. Well-dressed men make a run on the “Mechanic’s Bank,” which announces to depositors that “no specie payments” will be forthcoming, while soldiers march upon the unarmed crowd. No billows of smoke emerge from the stacks of the railroad engine or steamboat. Signs on the city’s offices, hotel, and factory respectively read “to let,” “for sale,” and “closed for the present.” A woman draws the shutters closed above the pawnshop of “Shylock Graspall.” A fort named “Bridewell,” an infamous English poorhouse and debtors’ prison, prepares to welcome a new inmate while a veteran tenant hangs from a gibbet. All the while, in an expression of visual gallows humor, the well-tended fields produce crops that have no hope of being transported to markets or of alleviating the hunger in the city.

“The Times” has become the iconic image of the Panic of 1837. It has graced the covers of monographs, collections of essays and conference programs, and appeared in textbooks as the definitive illustration of the financial crisis and the national depression that followed. But, in fact, this is a strange choice, for “The Times” looks nothing like most of the other images produced in America during and after the crisis. The latter blame the hard times on politicians and the political system, and are replete with monstrous figures and literary analogies, with little interest in conveying a realist account of the events of 1837. These images are rooted in a vision of economic life as inseparable from political and moral judgment. Nothing of the systemic neutrality and objectivity that we assign to the economy is in evidence here.

“The Times” also contains something of this earlier polemical convention. Clay set a scene of bank runs two months later than it actually occurred, for instance, in order to give it a more symbolic date, July 4, 1837. But his argument about the political causes of crisis remains at the margins. The suicide of several figures leaping out of a burning hot air balloon labeled “Safety Fund” alludes to problems with Democratic financial policy. Jacksonian emblems on the sun, together with several of his famous quotations, or “popular sayings,” suggest that the former president had something to do with the current hardships. In general, however, Clay’s vision was a distinctive image of panic that abjured convention by reflecting uncertainty about the cause of crisis. The vague, quasi-realism of “The Times” suggests that hard times have a recognizably timeless quality. Such a perspective was anathema to prevailing economic thought in the 1830s. At the same time, it allowed Clay to achieve immortality, for its generic imagery transcended time and place and so appealed to future generations using a vastly different lexicon to think about the economy.

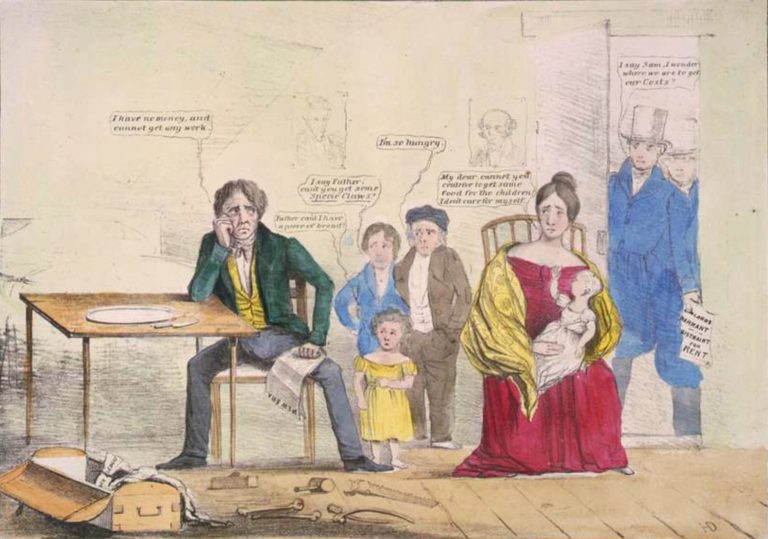

In 1837, Americans panicked. That, at least, is what they called their experience as the immediate financial crisis ended in May 1837 and they sought an explanation for the unfathomable, nearly universal failure of business. Before the crisis began, when the economy was still prospering, popular novels, domestic economy manuals, and even political economy textbooks taught contemporaries that individuals were responsible for their own economic successes or failures. When George Putnam preached his sermon, “The Signs of the Times” on March 6, 1836, for example, he imagined “the figures and coloring of a picture, a painted canvass prefiguring the moral history of the coming prosperous year.” This “crowded canvas” included stories of successful individuals who made smart, safe, frugal, and industrious choices, as well as failures who had abandoned morality in pursuing or convincing others to follow “visions of sudden wealth.” True, impersonal forces such as “the swelling tide of prosperity” or the “stormy sea of speculation” are found in Putnam’s word painting. The end result, however, lay with the individual who “plunges into a raging sea that he has never sounded, to work like a drowning man for his life, to sink or swim amid the stormy and treacherous waves.” To Putnam, as well as innumerable other pre-Panic writers in a variety of genres, individual souls bore responsibility for individual fates.

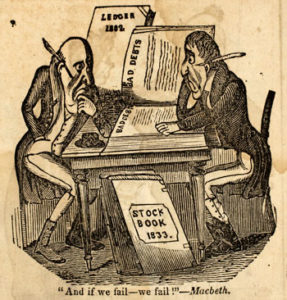

Within a year, Putnam’s prediction of continued prosperity proved disastrously wrong. Indeed, the financial crisis challenged the prevailing theory of individual economic responsibility. With the outbreak of troubles in March, individuals throughout the nation and across party lines struggled to find the words in letters, diaries, and newspapers to describe their experience. “The agitation, the panic, I may call it,” a New Yorker wrote to the National Intelligencer, “no pen can properly describe.” But many pens and even more printing type tried. The editor of the New Orleans Bee fumbled about for the right language, writing about “the excitement, the terror, the panic, or whatever you please to term the state of public feeling.” “In one word, excitement, anxiety, terror, panic, pervades all classes and ranks,” a correspondent from New Orleans wrote to a northern newspaper, incapable of restricting himself to merely “one word.” These examples are revealing of more than just a national failure to find a vocabulary to convey the economic reality. They point to the absence of a conceptual apparatus that could explain the crisis. The terms “capitalism” and “the economy” had not yet been invented. The latter still referred, for instance, to a frugal management of resources, either those of a household or of a nation, and not to a societal structure.

As the crisis intensified, the notion that each man assumed responsibility for his economic fate seemed increasingly flawed. Everyone, that is, was ready to claim credit for prosperity; none were willing to confess to personal failure. Across the ideological spectrum, ornate metaphors, similes, and tropes exposed the general desire to blame everyone and everything but one’s own choices. William Leggett, the editor of the New York Plaindealer, mixed his metaphors with abandon. In one brief essay he drew on the entire lexicon of panic: He described the nation’s business as “unhealthy,” as a “machine” that had been “thrown out of repair, if not broken all to pieces,” as a fabled frog that had been “blown up to unnatural dimensions,” or as “the dreadful consequences of a deluge of bank credit” produced by “effusion from the fountain of evil.” Whether the crisis was imagined in terms of contagious disease, technological disaster, fantastical horror, unpredictable weather, and divine (or satanic) test of human morality, it turned men into victims.

The less control observers exercised over their finances, the more they described their experience in terms that eliminated their personal economic agency and the more they used the word “panic.” According to the 1828 edition of Noah Webster’sAmerican Dictionary, the term referred to “a sudden fright; particularly, a sudden fright without real cause, or terror inspired by a trifling cause or misapprehension of danger.” Those who now adopted the term were determined to discover forces larger than themselves which had provoked the crisis. Moses Taylor, a New York merchant, wrote to his correspondents in Cuba that “we are at the present moment enduring a panic greater than has yet been felt in the US.” The scale and acuteness of the crisis seemed unprecedented, unique, and incomprehensible. As Taylor wrote to another correspondent, “it is almost impossible to conceive of the disastrous state of affairs here.”

In fact, the panicked victims of 1837 lacked the concepts that would guide later attempts to identify the causes of crisis. Twentieth-century economic historians have explained the troubles of the late 1830s and early 1840s as a result of small changes in monetary policies in Great Britain, the United States, and China, exacerbated by the enormous interlocking character of a global economy. In 1837 no one could see this as the cause of crisis since no one had the statistical tools, the historical perspective, and a century of economic theory for making such an argument. James Gilbart, an English advocate of democratized banking, argued that “the science of statistics has received till lately but little attention in this country, and perhaps, the statistics of banking have received less attention than any other portion of that science.” If statistical data had not yet become a feature of English economic thought, America barely accepted the theories of political economy, in words or numbers. When one of the nation’s first and most popular political economy textbooks, Francis Wayland’s The Elements of Political Economy, first reached readers mere months before the crisis, reviewers pointed out that “we meet with men grown grey in politics and legislation, who emphatically term the science of Political Economy a humbug, and its partisans a set of visionary schemers and theorists.” Macroeconomic monetary forces may have been at work in 1837, but contemporaries had no way of seeing them. Indeed, some contemporaries yearned for this type of economic overview. As Charles Francis Adams wrote in the summer of 1837, “one obstacle to the success of Political Economy as a science and consequent attention by practical men to its injunctions, is found in the difficulty of attaining a position elevated enough to look over the whole surface of action. Hence a danger of mistaking the relative importance of events, of giving to an exception the character of a rule, and of making a partial view weigh as much as if it was a general one.” The people of 1837 could not visualize the system they had not yet come to call “the economy,” let alone the crisis, from a macroeconomic bird’s-eye view.

While the present might have been difficult for contemporaries to see, the past proved no less difficult to bring into focus. They knew that economic history was full of “bubbles,” “revulsions,” “pressures,” and “panics.” Within a few decades, theorists would sketch the outlines of a business cycle. But in 1837 past crises were independent events the causes of which could be easily misunderstood and barely compared. Richard Hildreth argued in his The History of Banks (1837) that “the great pressure in the money market, produced by the high value of money, has been mistaken by practical men, whose experience does not extend beyond the panic of 1819.” The real parallel, Hildreth argued, was the “pressure” caused by the “scarcity of capital” during “the whole period from 1793 to 1808.” Few looked back that far. As recently as 1834, Americans had experienced a credit crunch when the B.U.S. contracted its loans after Jackson withdrew federal deposits. The cause of this much less severe crisis had been clearly political, namely, the bank war between President Jackson and B.U.S. president Nicholas Biddle.

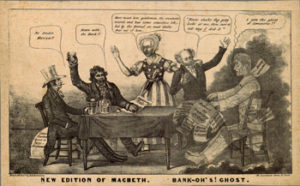

Politics provided the most obvious explanation for individuals who wanted to think of themselves as victims of an event caused by forces beyond their control. As one Senator excoriated, “some have the hardihood … to call it a panic, and to assert that it is manufactured, as if the public were feigning distress to make an exhibition of itself.” Politicians of all varieties used the idea of a manufactured panic to attack their opponents. Commercially oriented Democrats who had supported state-chartered over federally chartered banks blamed panic on speculating merchants who, in turn, sought to blame state chartering for causing their own “overtrading.” “Hard money” Democrats and working class Locofocos blamed banks of all kinds for fomenting an unnecessary panic in order to prevent the establishment of a specie currency. Whigs argued that the crisis was caused by the Jackson administration’s policies and called the event a panic in order to emphasize the role the federal government could play in ending this “experiment” with the nation’s financial system. Before the crisis ended, a coalition of New York Whigs and commercial Democrats called on President Martin Van Buren to convene an emergency session of Congress that would pass measures they believed necessary for restoring liquidity to financial markets and confidence to the nation’s foreign creditors. When Van Buren refused, they blamed his inaction for the panic’s severity. And when the bank suspensions forced Van Buren to call a “panic session,” he blamed the Whigs for manipulating the banks for political purposes.

Partisans of both sides therefore crafted a picture of national and impersonal panic that diverged from the local and psychological experience described by individuals in their letters and diaries. Only after the panic ended were references to meltdowns, tempests, epidemics, and biblical punishments replaced by arguments about victimization at the hands of the political system. The Bank of England was pushed far offstage. Instead, images of Jackson, Van Buren, Biddle, and the other politicians of the day came to dominate images of panic as well as the consequent writing of its history. The only figures who panicked in most of these accounts were the villains and heroes of national party politics.

Aside from a few crude engravings published in humorous almanacs in 1838, the only images of panic from 1837 are political cartoons. Most of these are single-page broadsides. One interesting exception is a bizarre pamphlet entitled Vision of Judgment, Or A Present for the Whigs of ’76 and ’37 which narrates the story of the Jackson and Van Buren administrations by means of beastly characters. Ironically, the words and the pictures in this allegory do not tell the same story about financial crisis. The text seeks to describe the panic as a human experience:

It happened, one cold morning, a little before sunrise, that an “awful explosion,” like an earthquake, was felt all over the plain, even to the farthest extremity. The whole nation were in the greatest consternation. Some thinking, from the rocking of the walls, that their houses were falling down on their heads, began to weep and lament in the most distressing and alarming manner. Others tore their hair in the agony and frenzy of the moment, running about and screaming in the most heart-rending tones; while others again gave themselves in sullenness to despair, and cursed the day of their birth. In short it would be impossible to describe half the distress and wretchedness produced on that dreadful and never-to-be-forgotten day.

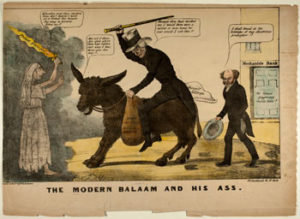

The accompanying image, however, a lithograph produced in Robinson’s shop, displayed none of the feelings conveyed in the text (fig. 6). It focused, rather, on how “the golden ball,” a symbol of the policies of Hard Money Democrats, “was found to have been hollow within and only gilt without.” “From it, as from the fabled box of Pandora, issued every evil thing which could be imagined,” the description continued, “Poverty, Distress, and Famine came forth, followed by a ghostly train, bearing in their arms whole bundles of paper.” To Whigs, these were symbols of the hypocrisy of Van Buren’s Subtreasury plan, a federal department whose creation was proposed in the summer of 1837 to protect government deposits from the suspended banks but would, like them, become an issuer of paper notes (or Subtreasury “rags”). Rather than illustrate the “never-to-be-forgotten” human suffering described in the words, the artist rendered an exclusively political argument.