Poetry over Politics

On a chilly evening in early December 1795, seven members of New York City’s Friendly Club convened at William Dunlap’s lodging for their weekly meeting. Dunlap opened the proceedings with a reading from Helen Maria Williams’s recent publication, Letters from France, and for nearly five hours, the attendees discussed literary works and debated current issues. Satisfied that the meeting had generated a stimulating conversation, Elihu Hubbard Smith recorded in his diary that “[t]his evening has been better spent, than usual.”

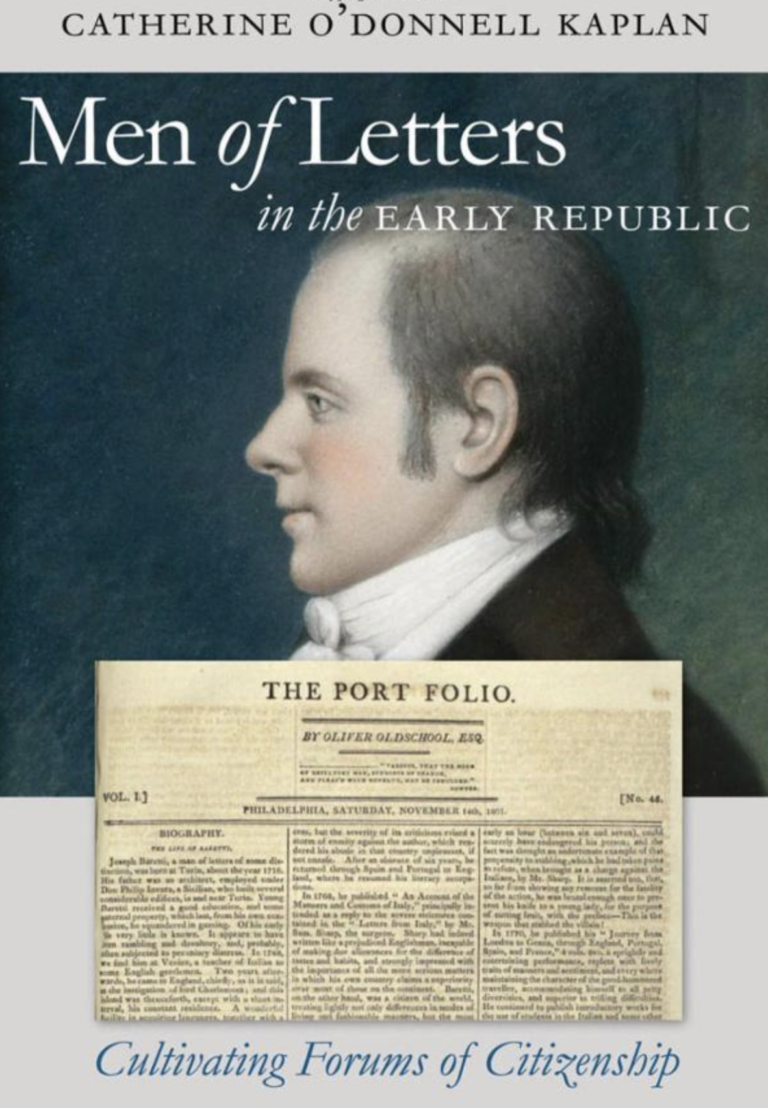

In Men of Letters in the Early Republic, Catherine O’Donnell Kaplan examines why Smith, along with many other young men residing in the Northeast, attached great importance to intellectual labor and exchange. These aspiring literati, Kaplan observes, perceived that belletristic endeavors were necessary for maintaining a healthy and harmonious society. Their vision of a national community bound by practices of sociability, sensibility, and learning constituted a radical critique to the notion that formal political participation defined citizenship, and this vision offered a welcome alternative to the intense personal and ideological partisanship of post-Revolutionary America.

In her investigation of how “men of letters” articulated a civic role for themselves and whether there was “a place and a use in the new United States for these men and their different kind of citizenship” (12), the author focuses on three sets of individuals and their affiliated literary networks: Elihu Hubbard Smith and the Friendly Club in New York; Joseph Dennie of Walpole, New Hampshire, and later Philadelphia; and the trio of William Smith Shaw, Arthur Maynard Walter, and Joseph Stephens Buckminster, who formed the core of the Boston-based Anthology Society and founded the Boston Athenaeum. Kaplan notes that these groups exhibited several shared traits, most notably adherence to social elitism, masculine identity, and transatlantic modes of polite culture. Even so, she goes on to show that they each formulated different models for social and political improvement.

For Smith, a physician and prolific author of prose and poetry, the accumulation and dissemination of all types of knowledge in a convivial setting was the means by which individuals effected change and “created harmony and pursued justice” (7). The aptly named Friendly Club provided a space where Smith could collaborate with others on projects of self- and social reform. Here he could converse with colleagues of various vocations—the novelist Charles Brockden Brown, the jurist James Kent, and the dramatist William Dunlap—about the progress of the local manumission society to which they belonged, discuss Brown’s latest novel or Dunlap’s latest play, or go over innumerable other topics. Friendly Club meetings, however, were only one of many literary venues available to Smith. As Kaplan surmises, “Rather than a self-sustaining circle, the Friendly Club was a node in a network of linked and interdependent groups” (43). Smith’s involvement with the Medical Repository and his frequent conversation and correspondence with women literati further demonstrate that the network contained overlapping realms of oral, manuscript, and print communications.

Like Smith, Joseph Dennie, a reluctant lawyer, created an active literary network, producing three periodicals with varied success—the Tablet in Boston, the Farmer’s Weekly Museum in Walpole, and the Port Folio in Philadelphia—and participating in Philadelphia’s Tuesday Club. Kaplan attributes the longevity and popularity of Dennie’s Walpole paper to his ability to create a geographically extensive network of “all those who read, wrote for, found subscriptions for, extracted, or even quoted the Museum” (122). To solidify his readers as a distinct community, Dennie employed an editorial style based on intimacy and humor. Although he lambasted overt partisanship, his writings nonetheless imparted Federalist sympathies. Moreover, unlike Smith, Dennie favored “ephemeral wit” over “empirical information” as a means of exposing truth (9).

For Bostonians Joseph Stephens Buckminster, a Unitarian minister, Arthur Maynard Walter, a lawyer, and William Smith Shaw, the clerk of the District Court of Massachusetts, belles lettres provided a refuge from the mundane and at times maddening world of “commerce and politics” (11). In contrast to Smith and Dennie, these men did not pursue a national framework for their reforming efforts, developing in its stead “a more parochial vision of cultural community” (189). Relying on an impressive literary network that spanned Boston and Cambridge, the Anthology Society revived the Monthly Anthology, a local periodical, and formed the Athenaeum, a private reading room that served Boston’s mercantile elite.

Kaplan concludes that although Smith, Dennie, and the Anthologists established “lasting forums and institutions,” such as the Medical Repository, the Port Folio, and the Boston Athenaeum, they nonetheless failed in their quest to transform notions of American citizenship (231). Even if their literary endeavors did not reconstitute civil society throughout the fledgling United States, the evidence presented in Men of Letters suggests that these belletrists did shape emergent cultures in local and regional spaces. As Trish Loughran has recently claimed in The Republic in Print (New York, 2007), transportation and communication deficiencies precluded the possibility of a viable national public in print. Kaplan’s examination similarly forces us to move beyond a national framework and to foreground the local and regional networks at work in the post-Revolutionary era.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.3 (April, 2009).

Robb K. Haberman is a Ph.D. candidate in early American history at the University of Connecticut. His dissertation is entitled, “Periodical Publics: Magazines and Literary Networks in Post-Revolutionary America.”