Potent Papers

Secret lives of the nineteenth-century ballot

Voting is meant to be the culminating moment in American civic life. It’s the answer to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service’s citizenship exam question, “What is the most important right granted to United States citizens?” And yet, like those out-of-time days spent on jury duty, going to the polls can feel less like a moment of decisive action than like the dream-life of citizenship, a surreal and unique event, whose meaning seems to inhere in its very isolation from everyday life.

The act of voting self-evidently centers on the ballot, but that item is so various in current practice as to be barely contained by one rubric. In Manhattan, where I have voted for decades, the “ballot” has long since disappeared behind the toggles and gears of the stalwart if vaguely Chaplinesque mechanical lever machine (yearly threatened with extinction, it was still in place, in my district anyway, in February 2008). You enter the polling booth through a curtain; now in effect inside the machine, you pull the lever to the left to close the curtain. Record your votes by turning handles (think pinball machine) next to the names and party symbols of your choice; pull the lever to the right to lock in your vote; and with that the curtain springs open and you spring out, your performance on the democratic stage enacted in secret. In Minnesota, I’ve voted by an optical scanning system, where the act is more in the nature of a literacy event, characterized entirely by the voter’s relationship to reading and writing practices. Here you are presented with a grease marker with which to fill in a gap in an arrow pointing to the name you want to vote for.

These and all other methods of voting used in America have in common a sacramental devotion to the secret ballot. But the secret ballot was an innovation of the late nineteenth century. Except for article 1, section 4, which assigns congressional election procedures to the states, the U.S. Constitution stayed silent on suffrage until the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, with the logistical details of voting always left to the states. The U.S. Supreme Court noted in Pope v. Williams (1904) that “the privilege to vote in a state is within the jurisdiction of the state itself, to be exercised as the state may direct, and upon such terms as to it may seem proper, provided, of course, no discrimination is made between individuals, in violation of the Federal Constitution.” Over time, then, the ballot has taken a variety of forms, consonant with the changing demands of local political cultures.

The technology of the ballot in the United States may be very loosely charted through four phases, from the Revolution through the nineteenth century: from viva voce, to handwritten and printed ballots, to printed party tickets, to the Australian or Massachusetts ballot, first adopted in the United States in 1888. This last is the result of a reform that introduced the genre that remains: the municipally published, nonpartisan secret ballot (though the technologies that mediate this ballot continue to be locally determined and to vary widely). By 1800, most states were, according to their constitutions, voting by “written papers.” Broadly speaking, this periodization of the ballot marks the transfer of authority and legitimacy from one medium to the next: from voice to hand to print to machine.

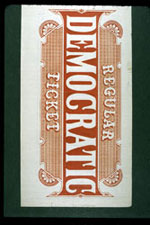

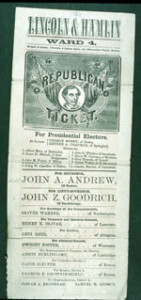

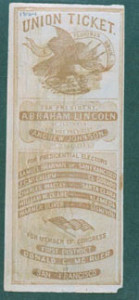

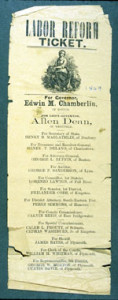

Before the secret ballot became the national standard, election ballots were a vivid genre of print ephemera. The examples here, drawn from the American Antiquarian Society’s cache of uncatalogued ballots, might suggest some ways of thinking about what “that most potent of all sheets of paper” (as the early twentieth-century editor and writer Philip Loring Allen called the ballot) has meant in the past. The ballot shares some characteristics with other print and manuscript genres. Like a contract, it is executable. It becomes the act that it represents, but it is inert until and unless it is activated. Like money, it has taken a wide variety of forms since ancient times. In the United States the ballot shares paper currency’s shifting institutional location, from private, entrepreneurial, and local to public and government-sponsored. Like street literature—handbills, newspapers, leaflets—the ballot promotes and advertises, and its delivery system links stranger to stranger in public spaces. Like a poster for an urban spectacle—a night at the theatre or at Barnum’s museum—its text consists of a dramatis personae headlined by seductive and hard-to-keep promises.

More than most print genres, the ballot is a hinge between the political and the personal, national vistas and hometown scenes, the sweep of public events and the nuanced rhythms of private life. If we usually think of ballots in the aggregate or in the abstract, those that survive in archives emerge as fragments of these multiple narratives.

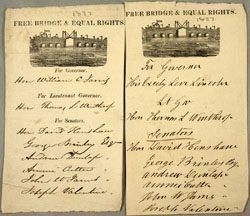

In 1829 in Massachusetts, the Jacksonian politician and newspaper editor David Henshaw (who appears on ballots in figure 1) presented a printed rather than hand-written ballot at the poll and was turned away for not having a “written” ballot as stipulated by the state constitution. In the resulting legal test, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that in this case “written” encompassed “printed.” Though printed ballots were used in other states, this judicial intervention marks a signal moment in the long transformation from rhetorical and manuscript culture, in which physical gestures and practices of the hand testify to legitimacy, to a culture in which products of mechanical reproduction can be authorized and even sometimes preferred to originals. Henshaw’s motives were pragmatically political. He had objected to party workers who would write out multiple ballots and try to press them on voters at the polls. He apparently hoped that the printed ballot would carry more legitimacy and would neutralize the power and convenience of the prewritten ballots, increasing voters’ access to a variety of tickets and hence to independent choice.

This was not by any means the universal outcome of this medial shift. The notorious printed ballot of the mid- to late century was produced by parties, in often partisan print shops, and handed out by party workers at the polling place. Voters were cajoled and corralled in bustling and raucous scenes (figs. 2 and 3), which took place in a wide range of venues. Sometimes a schoolhouse or a town hall would be reserved for voting, but anywhere—a barn or a bar—would do; one was handed a party ballot and in turn handed it over at the voting window.

In 1829 in Massachusetts, the Jacksonian politician and newspaper editor David Henshaw (who appears on ballots in figure 1) presented a printed rather than hand-written ballot at the poll and was turned away for not having a “written” ballot as stipulated by the state constitution. In the resulting legal test, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that in this case “written” encompassed “printed.” Though printed ballots were used in other states, this judicial intervention marks a signal moment in the long transformation from rhetorical and manuscript culture, in which physical gestures and practices of the hand testify to legitimacy, to a culture in which products of mechanical reproduction can be authorized and even sometimes preferred to originals. Henshaw’s motives were pragmatically political. He had objected to party workers who would write out multiple ballots and try to press them on voters at the polls. He apparently hoped that the printed ballot would carry more legitimacy and would neutralize the power and convenience of the prewritten ballots, increasing voters’ access to a variety of tickets and hence to independent choice.

This was not by any means the universal outcome of this medial shift. The notorious printed ballot of the mid- to late century was produced by parties, in often partisan print shops, and handed out by party workers at the polling place. Voters were cajoled and corralled in bustling and raucous scenes (figs. 2 and 3), which took place in a wide range of venues. Sometimes a schoolhouse or a town hall would be reserved for voting, but anywhere—a barn or a bar—would do; one was handed a party ballot and in turn handed it over at the voting window.

Voting was performed in public view; no matter how many times you folded the typical nineteenth-century ballot, there would be no mistaking what your vote was.

But secrecy was not always seen as a requisite or even desirable component of voting and wouldn’t become one by law until 1888; for some elections in some places, viva voce voting remained the norm for much of the century. Sociologist Michael Schudson vividly imagines the characteristic state of mind of the mid-nineteenth-century voter.

You are not offended in the least by this openness; indeed you want your party loyalty to be recognized. Your connection to the party derives not from a strong sense that it offers better public policies but that your party is your party…Very likely you have been drawn to your party by the complexion of the ethnocultural groups it favors; your act of voting is an act of solidarity with a partisan alliance. This is a politics of affiliation, not a politics of assent.

Whether every voter fit this model or not, the ballot nonetheless ostentatiously emblematized affiliation.

In the nineteenth century, the ballot was often indistinguishable in both form and function from campaign paraphernalia, turning voters into advertisers and promoters. These gaudily potent sheets of paper performed in much the same way as other print genres of the time, a “carnival on the page,” as the historian Isabelle Lehuu puts it. They converse with the riot of colorful print ephemera coming off the presses and circulating through urban and rural spaces: newspaper and magazine advertising, handbills, circus posters, playbills, railroad tickets and timetables, school rewards of merit, currency, and all manner of ephemeral job-printing. The ballot promotes and displays the printer’s art, using the visual jargon of publicity and advertising, the same techniques of engraving and headlining as any handbill, poster, or print ad. Ballots participate in the same public spectacle as other campaign activities, such as the rallies in which questions of public moment are subsumed in a general air of theatricality and festivity, speechifying and glad-handing.

Writing during World War II, the political scientist O. Douglas Weeks describes the ballot, in his introduction to Spencer Albright’s The American Ballot, as the “material object which democracy has sought to substitute for the battle-axe or the hangman’s noose and as an emblem and as a weapon in the settlement of civil disagreements.” If in the abstract the ballot strives to offer an alternative to violence, during the Civil War party ballots continue the political campaign as well as the war campaign. Some deploy battlefield imagery, in commemoration and exhortation to allies, with a warning to others.

Party ballots often display female emblems—Liberty, America, Columbia—as partisan iconography, evoking patriotic ideals as well as the presumed moral gravitas of the domestic and sentimental figure of the woman.

Perhaps most pervasively and suggestively, ballots mimic currency, in a family resemblance that goes deeper than the economic and monetary platforms of campaigns. Their saturated engraved designs imply counterfeit-proofing, making them look like deeds or stock certificates, positioning the ballot as a stake in the national joint-stock company. Like currency, the ballot is meant to function silently; only its purchase power and its meaning in aggregate are supposed to “count.” The individual ballot’s materiality, like that of currency, is meant to be subsumed by its symbolic value, expressed in its design. Just as counterfeiting undermines legal tender, ballot tampering threatens the legitimacy of the vote.

A ballot marked by actual handwriting, rather than its facsimile, can also remind us that the ballot is more, finally, than its political iconography, more than its value as a unit in an election count—more, that is, than a mere individual chirp indistinguishably merged into the vox populi. As we know from our own experience of voting, the ballot, whatever its material form (switching a toggle and engaging a gear; inscribing, poking, or punching paper, etc.), can be invested with emotions and ideas, hopes and dreads, fantasies and phantoms sometimes only obliquely related to politics or to civic life. Two ballots in the American Antiquarian Society collection retain the traces of such unquantifiable affect. John H. Evans, a young farmer in Freetown, Massachusetts, cast a ballot for John Quincy Adams II in the gubernatorial election of 1871 and kept one as a souvenir, using it to testify—”right smart stout”—to his vote. Just twenty-five in 1871, Evans would have been making one of his first trips to the polls. For Evans, ballot in box isn’t quite enough. His handwriting insists on the full-body presence of a particular voter as he also records the context for his vote, associating it with his day’s work on his neighbor Henry Winslow’s mill and with the company of his neighbor and coworker, Henry Pierce, who went with him to vote. By inscribing his ticket, Evans pulls the ballot out of circulation, out of its role in the aggregate, and into a unique relation to the voter. More than a scrapbook souvenir of the event, Evans’s ballot is a fair copy of the event, a snapshot.

![Figs. 26 and 27. On the back of this ticket, John H. Evans records the events of election day. "The Democratic ticket for the year 1871. I worked for Henry Winslow building wall for underpinning for his new mill and when the whistle blowed Henry Pierce and I s[t]arted for the polls and voted Democratic right smart stout." Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](http://commonplacenew.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/9.1.Crain_.26.jpg)

Ten years earlier, Augustus Russell Pope, born, like Evans, in 1846, used a ballot to send a melancholy letter to his uncle. Too young to vote in 1861, he dispenses with the election in the first sentence; the son of a prominent abolitionist minister who had died in 1858, Pope does note that the staunch Republican governor John Andrews has likely won. Then the young writer turns to his health woes and thoughts of joining the navy. But this youth writes as if to be “at sea” in 1861 is the same as it was in 1851. “Aug. R. Pope,” as he signs himself, is headachy and has a bad humor in his blood. He apologizes for “errors…and bad writing,” the result he says of haste and of his mother’s wish that he overcome his left-handedness.

Augustus Pope longed to be otherwise and elsewhere—to be strong and, like so many young men before him, to go to sea. As it happens, he enlisted in the Massachusetts infantry and died of dysentery in Andersonville Prison in August of 1864 at the age of eighteen. Young “Aug. R. Pope” never did get to vote. These personalized ballots register individual voices through the medium that’s designed to speak strictly in the composite vox populi. Their inscriptions exchange the ballot’s political value for an affective value in a private network making another kind of claim for the potency of the ballot.

Liz Hutter assisted with the research for this article.

Further Reading:

Most histories of voting are quite naturally devoted to politics and suffrage, per se, while the materiality of the nineteenth-century ballot cries out for further research. Useful in this regard is work on nineteenth-century print culture more generally, especially David Henkin, City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York, 1998) and Isabelle Lehuu, Carnival on the Page: Popular Print Media in Antebellum America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2000). For other examples of nineteenth-century ballots see Melanie Goodrich, 19th Century Ballots from California. Other Websites that helpfully place these ballots in context are: Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project and Douglas Jones’s Voting and Elections.

An excellent mini-history of the ballot, with a focus on the development of the secret ballot, is Jill Lepore’s “Rock, Paper, Scissors,” in The New Yorker (October 13, 2008): 90-96. For the history of voting technologies, see Roy G. Saltman, The History and Politics of Voting Technology: In Quest of Integrity and Public Confidence (New York, 2006). For an excellent description of the logistics of voting in the nineteenth century, see Richard Franklin Bensel, The American Ballot Box in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, 2004). For a history of the ballot, see Spencer Albright, The American Ballot (Washington, D.C., 1942). A recent and very fine history of the franchise is Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York, 2000). See also the essays collected in Donald W. Rogers, ed., Voting and the Spirit of American Democracy: Essays on the History of Voting Rights in America (Urbana, Ill., 1992). Also useful is an earlier work on early national and antebellum suffrage: Chilton Williamson, American Suffrage: From Property to Democracy, 1760-1860 (Princeton, N.J., 1960). For rich descriptions of nineteenth-century campaigning and voting, see Glenn Altshuler and Stuart M. Blumin, Rude Republic: Americans and Their Politics in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, N.J., 2000) and Michael Schudson, The Good Citizen: A History of American Civil Life (New York, 1998). A good general survey of presidential campaigns, with terrific illustrations, is Evan Cornog and Richard Whelan, Hats in the Ring: An Illustrated History of American Presidential Campaigns (New York, 2000).

The description of the ballot as “that most potent of all sheets of paper” is from Philip Loring Allen’s “Ballot Laws and Their Workings,” Political Science Quarterly 21 (March 1906). For the context of the David Henshaw printed ballot case, see Gerald J. Baldasty, “The Boston Press and Politics in Jacksonian America,” Journalism History 7 (Autumn-Winter 1980) and Arthur B. Darling, Political Change in Massachusetts, 1824-1848: A Study of Liberal Movements in Politics (New Haven, 1925). Henshaw v. Samuel H. Foster et al. is reported in Octavius Pickering, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts (Boston, 1883). For Massachusetts politics before Reconstruction, the context of many of the ballots here, see Dale Baum, The Civil War Party System: The Case of Massachusetts, 1848-1876 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1984). For woman suffrage and the Boston School Committee, see History of Woman Suffrage by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Gage, and Ida Harper, published by Susan B. Anthony in 1886. For the battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama see Juliet Wilson-Bareau, with David Degener, Manet and the American Civil War: The Battle of the U.S.S. Kearsarge and C.S.S. Alabama (New York and New Haven, 2003).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Patricia Crain is associate professor of English at New York University and the author of The Story of A: The Alphabetization of America from The New England Primer to The Scarlet Letter (2000).