Pressing Matters: An experiential study of the Isaiah Thomas printing press at the American Antiquarian Society

In 1756, Isaiah Thomas—newspaper chronicler of the American Revolution, eminent publisher, historian of American printing, and founder of the American Antiquarian Society—began a unique, nearly lifelong relationship with a printing press. Thomas’s mother had been impoverished when her husband left Boston to improve the family’s fortunes and instead died in North Carolina. When Thomas was six, she placed her son in the household of a printer, Zechariah Fowle, to whom Isaiah was formally indentured as an apprentice when he was only seven. Fowle’s modest Boston printing establishment depended on a single wooden printing press built in London in 1747 (fig. 1). It was not an unusual machine in its construction or design; it looked very much like other English “common presses” of the period. Thomas began his mechanical relationship by inking the press while standing on a box. Later, he learned to pull the press himself, and he seems to have quickly exceeded the abilities of his master. Some years after his apprenticeship ended, Thomas acquired the press from Fowle, and it was a mainstay in his establishment in the following decades. In 1796 he compiled an inventory of his by-then large shop, and in that document he referred to the press as “No. 1.” Notably, he also listed it as “old,” which may imply that the press was little used or even retired. In 1812, Thomas founded the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, and in 1830 he wrote a codicil to his will that left his then disassembled press to the Society. Thomas died in 1831.

The decades between Thomas’s apprenticeship and the revision of his will are changeful ones for the history of the hand press in North America. During those seventy-four years, the American importation of English common presses dwindled and native production became the rule; the design of wooden presses was subtly or more substantially improved by increasingly specialized press makers; and yet in spite of such improvements, by 1830 the wooden press was being pushed aside by the iron hand press. These developments, of course, took place within the larger transition of materials and processes that we traditionally designate as the industrial revolution. Thomas’s machine, which today presides over the reading room of the American Antiquarian Society from the second-floor balcony, helps us to glimpse these technological developments. As I describe below, having examined the press and its history closely, and having “embodied” that examination in the creation of a replica, I feel better able to speculate in an experientially informed way about the context for press innovation during this period.

Let me begin by recounting my own relationship to the Thomas press. Since 2007, I’ve been developing a letterpress studio and workshop associated with Special Collections in the Claremont Colleges Library. Students at the Claremont Colleges who take the workshop can learn to print on one of several iron hand presses. Working with these beautiful machines over the last few years, I became interested in how iron presses quickly replaced the wooden common press in the United States between 1814 (when George Clymer began to market his iron Columbian press) and 1840. In talking to my letterpress students about this technological transition, however, I found myself stumbling occasionally when speculating about why iron presses made wooden ones obsolete. I’d never worked with a common press, and I didn’t know enough about them to offer a very convincing narrative of their decline. With a year-long sabbatical leave in view, I decided to address my lack of direct knowledge about common presses in a somewhat unusual way: I prepared to build one, and “learn by doing” became my motto. Studying the press “by hand,” I thought, would help me to understand the technology and better construct my replica. I had long admired the Thomas press, one of a small number of remaining eighteenth-century common presses in the United States, and so I chose it as my original. While I’m not quite finished building my replica as I write this article, I’m close enough to draw a few conclusions about what I’ve learned through this experiential study. This is the point at which I should note that while I had a little experience with carpentry and metal work prior to this project, I had never tried anything remotely as large and complicated.

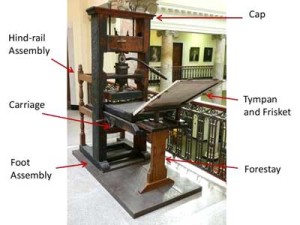

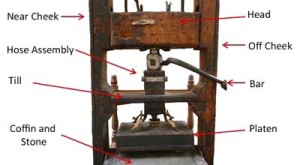

I began my project in fall 2011 by spending a month at the American Antiquarian Society studying the mechanism, history, and historical context of the Thomas press. When not examining printed and unpublished sources in the reading room, I could generally be seen by other readers on the balcony above them leaning over or crawling under the press, tape measure and calipers in hand. I spent many of my evenings and weekends drawing a set of plans from measurements and rough sketches, constantly comparing my drawings to the diagrams and descriptions in Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises on the Whole Art of Printing and Elizabeth Harris and Clinton Sisson’s The Common Press. I also consulted a number of early nineteenth-century printing manuals to make sure that I was correctly understanding and accurately representing the many pieces of the press. (The curators reasonably restricted my examination of the press by not allowing me to disassemble the spindle, nut, and hose, so for the dimensions of these pieces I relied on Harris and Sisson, who documented a very similar press at the Smithsonian Institution.)

One of the first things I noticed, something that would be obvious to even the most casual of observers, was that this machine had been well used. Ink covers much of the wood work, various parts have been gouged by nails or other sharp tools, the bar handle has been smoothed by the hands of many journeymen printers, and overall the press has the worn but proud look of an old veteran. On closer examination, however, I could see clearly what the more careful eyes of curators and conservators had previously noted: that this veteran is not completely original. Many parts have been repaired substantially, and a few of them have been replaced. Frustratingly, these alterations often don’t tell us much about when they were made or by whom, although there are clues that allow for some educated guessing.

Because some of these changes to the press as originally built seem dedicated to keeping it in working order, it is tempting to speculate that they date from Thomas’s lifetime. For instance, a wooden frame called the coffin was stabilized by driving nails into some of the joints and repaired by laying in new pieces (fig. 4). The coffin is an essential part of the machine: it holds a planed stone on top of which the type stands during printing. Wrought-iron flanges are nailed into the corners of the coffin, and the chase, the iron frame that holds the type in place on the stone, is wedged against these pieces. Over time, this wedging probably loosened and perhaps broke some of the wood in the coffin, necessitating the repairs that are now evident. This and some other repairs would have been worth making while the press was still in use; it seems unlikely that they would have been made later for the purpose of displaying the press.

Other alterations, though, are certainly more recent. Some may date from immediately after Thomas’s death. In the codicil to his will, Thomas instructed his grandson Isaiah Thomas Simmons to reassemble No. 1 and ensure that it was “well fixed” by Simmons himself or by “some Printer experienced in the construction of old-fashioned Printing Presses.” What exactly needed fixing and whether Simmons actually followed his grandfather’s instruction is unknown. The press was certainly altered later in the nineteenth century, but the extent of the changes is similarly hard to determine. In 1876 the press was loaned to Andrew C. Campbell, who owned the Campbell Printing Press and Manufacturing Company, for a display at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Corresponding with Samuel Foster Haven, the librarian of the Society, Campbell noted that “there was a part of it [the press] gone.” To which particular part or parts Campbell referred is unclear. That he didn’t really know much about the Thomas press—he identified it as having been built by Willem Janzoon Blaeu around 1680 in Germany—didn’t stop him from renovating the machine. He almost certainly replaced the hind-rail assembly and the forestay. Because he intended to print with the press while it was on display, he seems to have added a bolt and a new cross member to stabilize the foot assembly and to have repaired the damaged platen by cutting it down to its present size. (In 1977 a sliver of wood from the platen was sent to a laboratory which identified it as a species of maple, possibly as American sugar maple; the platen modified by Campbell, then, may itself be a replacement built after the press arrived in Boston around 1750.) The press that Campbell returned to the Society was thus a significantly altered machine from the one that left it.