Rainbow’s Mail-bag

Jacob Abbott was the Mister Rogers of the mid-nineteenth century. An icon of children’s education and entertainment, he wrote and edited over 200 books that, according to an anonymous 1843 review in the Salem Register, taught children “lessons of wisdom, goodness, and truth.” Like Mister Rogers, Abbott was an ordained minister who was warm and gentle in his approach. And, living in Vermont, Abbott likely wore a lot of sweaters, too.

Despite being one of the most prolific writers of the nineteenth century, Jacob Abbott is largely forgotten today. Compounding the fact that he wrote for children, his books gather dust because they are seen as racially and politically conservative, betraying what Donnarae MacCann identifies as a pervasive “ambivalence toward Blacks” throughout his oeuvre. This assessment, however, may be too dismissive. While Abbott’s books are not explicitly political, they did, at times, sensitively respond to racial injustices particular to the middle decades of the nineteenth century. One series of Abbott’s books in particular, The Stories of Rainbow and Lucky, offers a vision of a more just world, free of slavery and institutional racism.

Published between 1860 and 1861, The Stories of Rainbow and Lucky is a five-volume series of children’s novels that chronicle the adventures of Rainbow, a fourteen-year-old African American boy and his roguish horse Lucky (fig. 1). Rainbow is independent, hardworking, trustworthy, and intelligent—a characterization that prompted literary critic Robin Bernstein to identify Rainbow as one of the few “fictional black child characters that were complex and mostly or fully realized” in the nineteenth century.

The Stories of Rainbow and Lucky: Up the River, the final volume of the series, begins with Rainbow’s appointment as a post rider on a frontier postal route. Beyond delivering the mail, Rainbow finds time to help his neighbors build a house and to win over once-racists as friends. To be sure, this is an overtly moralistic tale; like Abbott’s other protagonists, Rainbow models the value of hard work and positive thinking. And yet, within the parameters of morally appropriate children’s literature, Up the River subtly engages with a contemporary debate about race, mobility, and black citizenship. By recontextualizing Up the River alongside contemporary postal policy, this essay uncovers the ways the novel artfully advances an ethos of racial equality on the eve of the Civil War.

Race and the Post Office

While the antebellum post office might not be the first place one would imagine to be a racially contentious institution, in Rainbow and Lucky’s nineteenth-century world, it was precisely that. After the Haitian Revolution, Postmaster General Gideon Granger forbade people of color from postal work, decreeing that “no other than a free white person shall be employed in carrying the mail of the United States.” Granger’s correspondence on the edict explains that “After the scenes which St. Domingo has exhibited to the world, we cannot be too cautious in attempting to prevent similar evils.” This letter, like the restriction itself, betrays a fear of a mobile, literate, and well-connected black community. Granger continues:

The most active and intelligent [black men] are employed as post riders. These are the most ready to learn, and the most able to execute. By traveling from day to day, and hourly mixing with people, they must, they will acquire information. They will learn that a man’s rights do not depend on his color. They will, in time, become teachers to their brethren. They become acquainted with each other on the line. Whenever the body, or a portion of them, wish to act, they are an organized corps, circulating our intelligence openly, their own privately.

Their traveling creates no suspicion, excites no alarm. One able man among them, perceiving the value of this machine, might lay a plan which would be communicated by your post riders from town to town and produce a general and united operation against you.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the post office was the fastest way to spread information over long distances. Government officials saw it as a powerful “machine” that could be harmful in the wrong hands. The Postmaster General reasserted race-based restrictions on personnel in 1810 and again in 1825—it wasn’t until 1869 that the U.S. Post Office Department lifted the restriction and began to hire people of color to carry the mail.

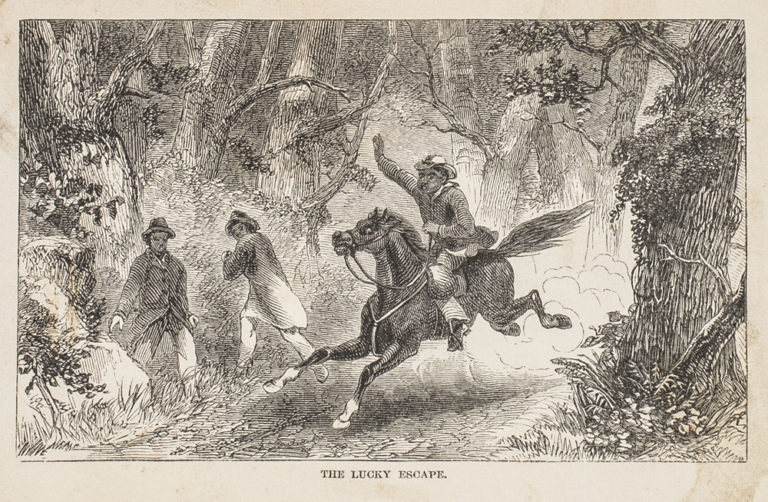

Accordingly, Jacob Abbott’s casting of Rainbow as a post rider in the early 1860s when the restriction was still in place was likely to raise an eyebrow or two. Suited with his mailbag and ready with the phrase “I bring the mail,” Rainbow travels freely through the woods on his frontier route (fig. 2). Like the insurrectionary black post rider the Postmaster General feared, Rainbow’s mobility is unremarkable and his integration within the community is routine. In the world of the novel, however, Rainbow does not use his position to incite rebellion. Instead, as a post rider, he is a trustworthy and important member of both the local and national community. People rely on Rainbow for their communication and welfare—and, for his efforts, he secures a generous government paycheck.

The novel’s acute awareness of postal policy makes Rainbow’s representation all the more subversive. In fact, Up the River is a veritable guide for rural mail delivery in the nineteenth century. For one, Rainbow signs a contract to carry the mail that follows the conventions of contemporary carrier contracts (fig. 3). Among other minutiae, Rainbow’s contract includes precise delivery and departure times that follow different schedules in the winter and summer. And, as the local postmaster warns Rainbow, “every time you fail of getting [the mail] here … there will be five dollars to pay,” which was precisely the fine for each lapse in mail delivery levied by the U.S. Post Office Department. Moreover, the process of mail-sorting is detailed over several pages: in both the novel and historical practice, after the specified mail was removed and the outgoing letters were put in their place, the local postmaster “would pass the chain through the staples and lock the padlock” of the mail bag for the carrier to bring to the next office down the road (fig. 4). The only departure from standard postal procedure is Rainbow’s appointment as a young black post rider.

Throughout the novel, Rainbow’s mail-bag invests him with the full confidence of the federal government. This confidence reaches its peak when, despite her surprise, a local teacher asks no questions when Rainbow and Lucky, strangers to her, bring a white princess-like child to school, even though “Rainbow saw by the expression in the teacher’s face, and also in those of the scholars, that they were curious to know who he was, and yet that they did not think it proper to ask.” Here and elsewhere the novel recognizes the subtle racism of community members who question Rainbow’s authority as a mail-carrier. In an encounter with a stranger on the road, for example, a woman greets him and curtsies—a “mark of respect” she would not have given “a colored boy under ordinary circumstances, but the fact that he was a mail-carrier invested him with great dignity in her eyes.” In both instances, readers are made aware of the double standard to which Rainbow would have been held as a mobile black youth. But equipped with the authority of his mailbag, Rainbow carries on free from racist constraints. Accordingly, unlike other African American child characters in sentimental fiction, Rainbow faces discrimination but is not defined by it.

Beyond staging these fleeting encounters with racism, The Stories of Rainbow and Lucky dwells on race-based structural inequality and how it affects Rainbow in “Rainbow’s Journey,” the series’ second volume. The day after leaving his mother’s home, for example, Rainbow reflects on “the strangeness of the situation he was in” as a young black man away from home for the first time. He considers:

A white boy, if he is of an amiable disposition and behaves well, even if he goes among entire strangers, soon makes plenty of friends. The world is prepared every where to welcome him, and to receive him kindly. But a boy like Rainbow feels that his fate is to be every where disliked and shunned … He expects, wherever he goes, and however bright and beautiful may be the outward aspects of the novel scenes through which he may pass that every thing human will look dark and scowling upon him.

In this meditation, Rainbow articulates an almost impossibly clear formulation of the structural inequality that shaped his social world. For a prospective young African American reader, such a representation would have been an invaluable validation of their experience. Further, the novel challenges white children to face the realities of racism and to empathize with “[boys] like Rainbow.” Arriving late in the second book of the series, this passage would have been especially poignant for readers who had come to care deeply for Rainbow.

But Rainbow is not the only character who faces racism in the idyllic world of the book series. Toward the end of the novel, Lucky, a young and handsome black horse, is captured by white thieves and forced into labor for them. To take Lucky without alerting the neighbors, the thieves paint him with “a broad white stripe down the middle of his face.” In doing so, the novel casts slavery’s racial power structures—where the difference between liberty and slavery is dependent upon color—onto an animal character. While enslaved, Lucky “bore … indignities patiently, secretly resolving, all the time, that the worse his captors treated him, the more watchful he would be for a chance to make his escape.”

Lucky plans and executes an escape that closely follows the conventions of contemporary slave narratives. While on the road, for example, “whenever he saw any body coming, he looked attentively at them to see if they were colored. When he found that they were white, he dodged off into the woods and hid there until they had gone by.” In the end, Lucky makes his way back home where Rainbow washes “his face with spirits of turpentine, and then Lucky was himself again.” Taken together, Rainbow’s postal authority and Lucky’s zoomorphic slave narrative mediate contemporary politics through the generic conventions of morally appropriate children’s literature.

Representations Fit for Children

The Stories of Rainbow and Lucky: Up the River demonstrates that young black men could occupy trusted positions of authority. And, by extension, the book contends that African Americans like Rainbow really were reliable, capable, and trustworthy members of local and national communities. In this respect, the comparison between Jacob Abbott and Mister Rogers bears still more fruit. Like Abbott, Fred Rogers fought for positive representations of African Americans at a pivotal moment in U.S. history. Weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and amid scenes of police brutality in black communities, Rogers introduced Officer Clemmons, a black police officer, to his neighborhood. Of course, neither Rainbow nor Officer Clemmons are radical figures, and, in many respects, these characters are politically conservative idealizations that suggest centuries of racism can be smoothed over by present goodwill.

And yet, these representations do matter. Rainbow and Officer Clemmons are part of a utopian vision that at once suspends and transcends racial inequality in the United States. Even as they evoke the often troubling politics of respectability, these characters encourage a pattern of feeling in which racism and white supremacy are recognized as great wrongs—an affect that children could transpose on their own worlds. A child in the nineteenth century could likely detect that Rainbow’s experience as a post rider was exceptional. White society treats Rainbow with dignity and respect, which was not always the case in the world outside of the novel. This kind of representation, at its best, challenges young readers to think critically and creatively about the world in which they live.

When read in the context of the nineteenth-century post office, however, The Stories of Rainbow and Lucky’s politics are revelatory: the story takes radical sentiments of racial equality and reframes them as non-controversial truths. By simply representing the existence of a black post rider doing his job, the novel refutes claims that mobile black men were threatening. The novel does not have to make big claims, because within this context, the existence of a black postal rider is itself one big claim.

Further Reading

For more on the history of the U.S. Postal Service in the nineteenth century, see Richard John’s Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (1995); and David Henkin’s The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America (2006). For literary studies that more directly attend to the effects of the postal system’s race-based exclusions, see Hollis Robbins’s “Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry Box Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics”; Susan L. Roberson’s “Circulations of Body and Word: Women’s Slave Narratives” in Antebellum American Women Writers and the Road: American Mobilities (2011); and Elizabeth Hewitt’s “Jacob’s Letters from Nowhere” in Correspondence and American Literature, 1770-1865 (2004). To consider the legacy of these nineteenth-century race-based exclusions as it manifests in the twentieth-century, see Philip F. Rubio’s There’s Always Work at the Post Office (2011), which uncovers the post office as a crucial part of African American history.

On the racial politics of children’s literature, see Robin Bernstein’s Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (2011); and Donnarae MacCann’s White Supremacy in Children’s Literature: Characterizations of African Americans, 1830-1900 (1998). For a broader understanding of how politics manifest in children’s literature, see Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature, edited by Julia L. Mickenberg and Philip Nel (2010). For more on how Fred Rogers’s politics influenced the casting and content of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, read Michael Long’s Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers (2015).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.1 (Fall, 2016).

Christy L. Pottroff is an Andrew W. Mellon Dissertation Fellow in Early Material Texts at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and a PhD candidate in English at Fordham University. Her dissertation examines the surprising extent to which the U.S. Post Office Department influenced early American literature.