Reading Distance

I will begin with a letter. It was sent on May 18, 1789, from Benjamin Franklin’s goddaughter, Amelia Evans Barry, to her childhood friend, Sarah Franklin Bache (fig. 1). With her itinerant merchant husband, Barry had spent her adult life traveling the world and found herself, in the tense European spring of 1789, between Holland and Italy. Bache had spent the intervening years in Philadelphia, where her father had returned.

My dear Madam,

You, who have been separated during a series of years from your excellent father, will know by experience that where affection is sincere, it is augmented rather than diminished by absence. Our infantile amusements and pursuits I have never forgotten; our little contests for superiority characterising us and America, desirous of independence, often occur to my memory, but like our country at that time we were not fit for it; and one or other conceding immediate reconciliation took place. It has not been in the power of 27 years absence to efface these scenes from my memory.

In Europe I have often thought of you; on the African shore you have been tenderly remembered by me; and in Asia tho’ we were separated by the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and Egean Seas I have not forgotten you. Permit me then to hope that these sentiments have been reciprocal; and that in the lapse of time the idea of your Amelia has not been totally obliterated, tho’ we may meet no more. I have often wished to return to Philadelphia, but superadded to the repugnance I should have to cross again the Atlantic Doctor Hawkesworth has contrived to repress this desire, by so finely portraying the situation of a man who returned late in life to his country; and the changes that have taken place in America would make every scene as new to me as countries that I have never seen. Doctor Johnson’s Imlac occurs to my mind. After having related to Rasselas the events of his life to the period of his return to his country with a mind improved by knowledge & travel, he says “I now expected the caresses of my kinsmen and the congratulations of my friends, but I was soon convinced that my thoughts were vain. Of my companions the greater part were in the grave and of the rest some could with difficulty remember me and some considered me as one corrupted by foreign manners.” This would certainly be my case should I return to Philadelphia. It must then be in a better world that we are to meet.

Tho’ I well know that the resentment of individuals against persons invested with supreme authority is as ridiculous as impotent, yet I was very angry with your congress for not permitting my dear Doct[or] Some year ago to resign his employments as he had in contemplation a visit to Italy; and perhaps our benign climate might have induced him to remain here which would perhaps have drawn you hither. What a scheme of felicity has been interrupted. Do me the favour to present my best compliments to Mr Bache and to all who are dear to you and ever believe me, dear Madam, your affectionate friend and servant, A. Barry.

Barry expresses many of the assumed conventions of women’s correspondence of this period: the assurance of affectionate sincerity, the strength of sentimental proximity over geographic distance. This is surely an émigré displaying her warm regard for the friend of her youth. But is this all that she is saying? Her connections between personal identity and the idea of America are quite hard to make sense of. Bache and Barry’s conflicts and resolutions, their growth toward independent adulthood, mirror their nation’s transition from dependence to sovereignty (“our little contests for superiority characterising us and America”). This is a powerful analogy for female friendship, but it is hardly a happy one. If maturity is independence then it is estrangement too. But perhaps another relationship—that of godfather to goddaughter—is equally important in this letter.

Barry maintained an admiring correspondence with Franklin while her association with Bache had lapsed. In an earlier letter she recalled for him “the scenes of childhood [when] your two little girls strove who should obtain [the] distinction of your notice.” The struggle that defines Bache and Barry’s friendship is as much about their relationship to competing versions of father-Franklin as competing images of nationhood. Franklin, in fact, is everywhere in Barry’s letter. His movement between continents (and the two women) seems to mark the distance between two identities: international enlightenment and domestic patriotism. Franklin thought of Barry as representing the former. “Her father . . . was a geographer,” he wrote of Lewis Evans, “and his daughter has now some connection I think with the whole Globe; being born herself in America, and having her first child in Asia, her second in Europe, and now her third in Africa.” (fig. 2) Evans’s geography is written out in his daughter’s itinerant maternity, reproducing the global enlightenment in a family of continents. Barry is clearly aware of how transatlantic exile might be read as exemplary. Her list of oceans (across which only the memory of Bache moves) has a numinous quality, and she compounds her own exoticism by making herself the subject of a voyage or oriental tale, trading the loss of her father/country for an expansive cosmopolitanism.

In its intermingling of the national, the paternal, the feminine, and the global, this letter is perhaps not quite the warm epistle of friendship it purports to be. While Barry claims the identity of an enlightened peripatetic, Bache implicitly represents an inert nostalgia: the patient homeland reaping the fruits of independence in the return of the absent patriarch. And perhaps, too, there is something of an anti-federalist swipe in the “supreme” authority that impedes Franklin’s projected Italian journey. This letter is hardly a paean to enduring sentimental ties or transatlantic attachment. Rather, it bears testimony to the imagined strength of an old rivalry between a Philadelphian who might read nationalist triumph in the return of her father (a figure for the nation and the age) and an embattled American wanderer, who wanted to regard herself as a citizen of the world.

Barry’s intriguing letter highlights some concerns of my current research. My project looks at the politics of women’s epistolary and manuscript culture in and around revolutionary and early republican Philadelphia. I came to this research from some work I had done on the Massachusetts writer Mercy Otis Warren, and I had quite predetermined ideas about what women’s letters were for and what they might do. When I started work with the Philadelphia sources, what I thought I was going to find most interesting about them was the sense of community, solidarity, and cultural connection one so often sees in circulated texts—I thought I was going to be most interested in women’s letters, journals, and commonplace books as agents of attachment. And while the ways in which manuscripts defined the bonds between women is incredibly important, I was much more struck by how their apparent connectedness (the connectedness of the form) belied a deeper sense of disconnection many Philadelphia women felt in relation to their political and literary cultures, their religions, their region, and their nation. Barry’s letter suggests the complexity of her feelings of detachment from her native Philadelphia. There is a hesitancy behind her confident mobility, a certain emptiness somewhere beyond the stylized bravado. For her, the idea of country seems profoundly bound up with the sense of loss. And this loss is suggestive of the ways in which the familiar letter reproduces absence.

As I worked on Mercy Warren, I often thought about how the letter made a writer present to her audience and how circulated texts afforded vicarious mobility to women who never moved beyond their local communities. It was just a shift of emphasis, perhaps, but with the Philadelphia sources I became powerfully aware of manuscripts as signatures of distance, as frail memorials of the space that divided the hand that wrote from the eye that read. This became particularly acute when working on Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson (1737-1801) at the Library Company of Philadelphia. Fergusson is often written about as the first American salonière, transplanting European culture to colonial Philadelphia. But this figure of successful literary cohesion was not who I encountered in her writing. In fact, I found a divided identity—one assumed and one expressed—in the difference between the appearance of her gift-books and their contents.

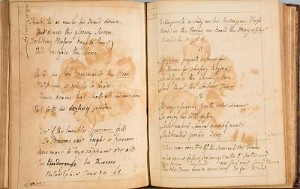

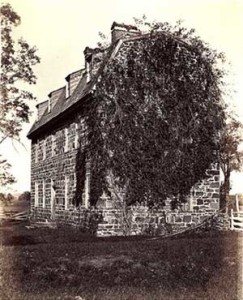

Fergusson’s beautiful gift-books, such as her Poemata Juvenilia, are persuasive objects (figs. 3, 4). Expensively bound and stamped, their author’s projected identity is proclaimed on the inside boards with the coat of arms, which marked the Graemes’s inherited attachment to a British (if by then imaginary) sense of class. But the hubris of the objects themselves—their sense of their own cultural importance and place—belie the disconnection and insecurity that dominated all that Fergusson wrote. As a transatlantic traveler she described herself as Odysseus out of Ithaca and later accounts of her position in revolutionary and early republican Pennsylvania refine this theme of detachment. Despite (or perhaps rather because of) her intense sense of entitlement, Fergusson’s ambiguous marital status, her indefinite political affiliations, her uncertain economic position, and her provisionally owned property were marked with an ambivalence that her writing revisits (fig. 5).

This ambivalence is not just a question of what Fergusson’s words say or mean but of the production and reproduction of her books themselves. Fergusson pressed them on a network of friends and readers, also revising them over long decades: reworking lines, adding notes and marginalia, later disguising her more virulent attacks on Pennsylvania’s revolutionary government, and returning to hone the vocabulary of her estrangement with frenetic, melancholy repetition (figs. 6, 7). Then the books were circulated again, or reproduced, with other readers in mind. Circulation here speaks less the language of literary community than that of lonely remonstrance.

Fergusson’s itinerant gift-books formed an analogy with her own rootlessness. Whether she was in London, the Scottish Highlands, or Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, the landscape and her writing mirrored her dislocation, her sense that this was not her country. Fergusson had a profound awareness of what national attachment might mean to a woman like her but somehow could never connect herself to it (one of her writing’s most conspicuous fantasies involves the figure of an exiled queen). Her awareness of her estrangement (from husband, family, class, land, and country) was specific but by no means unique. From radical Edinburgh émigrés to loyalist exiles, from democratic republicans to disenchanted federalists, the women of Philadelphia all articulated their particular sense of distance from the new United States. This distance does not mean that nation was less important to these women as archetype or value. Rather, in a world where personal bereavement and familial separation found potent geopolitical analogy in international conflict, nationhood represented for them a lost ideal, the scene of melancholy remembrance rather than patriotic attachment. In very different ways, then, for the women of Philadelphia the sense of place was also the sense of loss.

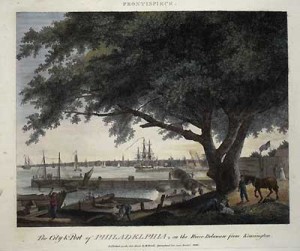

When I began research on Philadelphia’s incredibly diverse revolutionary and early republican women writers, I had hoped to explore the different facets of manuscript culture as community (in a particularly gendered sense). But as I found the circulated text to be as much about absence as propinquity, so I discovered that letters did not so much bespeak collective identity as thematize detachment. This detachment is there in Mary Hewson’s admission to her absent relations that in Philadelphia she felt as distant from the concerns of Washington’s administration as she had in Britain from those of the British government. It is there in Rebecca Gratz’s protests against the false promises of American bourgeois society: “the world has deceived me and I will in my truth deceive it.” This detachment is there in Elizabeth Wister’s poems, picturing the effects of national pride in the abandoned “hamlet . . . ravaged by conquest and war.” And it is there too in Deborah Norris Logan’s melancholy reflections on Philadelphia’s modernity and familial marginality as she watched the smoke of the city rise from a safe distance across the Delaware (fig. 8).

In her letter to Sarah Bache, Amelia Barry had other readers in mind. She was also responding to her godfather’s suggestion that she “return, as I have done, to your native Country.” And her letter speaks past its addressee to an archive and a history of women’s manuscript writing where nationhood is the stuff of memory and distance, of disaffection and desire. It tells us of how eighteenth-century letters, and eighteenth-century identities, might be about where you were not.

Further Reading:

Significant manuscript collections of the women mentioned in this essay are held at the American Philosophical Society Library (APS), Dickinson College Library, Haverford College Library, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP), the Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP), and the University of Pennsylvania Archives. Among the excellent existing work on Philadelphia women and revolutionary/early republican political and literary cultures see particularly: Catherine Blecki and Karin Wulf, Milcah Martha Moore’s Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America (University Park, Pa., 1997); Anne Ousterhout, The Most Learned Woman in America: A Life of Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson (University Park, Pa., 2004); Susan Stabile, Memory’s Daughters: The Material Culture of Remembrance in Eighteenth-Century America (Ithaca, N.Y., 2004) and her introduction to Ousterhout’s biography; Karin Wulf, Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia (Ithaca, N.Y., 2000); and Judith Van Buskirk, “‘They Didn’t Join the Band’: Disaffected Women in Revolutionary Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania History 62:3 (1995): 306-329. Exciting new work on eighteenth-century epistolary and manuscript writing includes: Clare Brant, Eighteenth Century Letters and British Culture (Basingstoke, England, and New York, 2006) and Eve Tavor-Bannet, Empire of Letters: Letter Manuals and Transatlantic Correspondence, 1680-1820 (Cambridge and New York, 2006).

The letter from Amelia Evans Barry (b. 1744) to Sarah Franklin Bache (1743-1808) is in the Sarah Franklin Bache Papers, APS. Other quotations are from the Franklin Papers (Amelia Barry to Benjamin Franklin, February 9, 1789; Benjamin Franklin to Deborah Franklin, July 22, 1774; Benjamin Franklin to Amelia Barry, October 14, 1787); the Gratz Family Papers, APS (Rebecca Gratz [1781-1869] Poem, “Lebanon Springs, 1806”) and the Eastwick Collection, APS (Elizabeth Wister [1764-1812] to Charles Wister, n.d. [1803]). Barry’s comparison of herself to Johnson’s and Hawkesworth’s protagonists refers to Imlac in Samuel Johnson’s The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia (1759) and the explorers of John Hawkesworth’s Account of the Voyage . . . for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere(1773). Other references are to Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, “Some lines upon my first being at Graeme Park after my return from England, August 16, 1766,” in Poemata Juvenilia, LCP; and the Fergusson/Benjamin Rush Correspondence, LCP; Mary Hewson (1734-1795) to Barbara Hewson, April 22, 1789, Hewson Family Papers, APS; Deborah Norris Logan (1761-1839) “An Afternoon Visit” (no date) HSP (Phi 379 no. 60).

The author would like to thank the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the Leverhulme Trust for fellowships that have enabled her to pursue research on this project.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.1 (October, 2006).

Kate Davies is the author of Catharine Macaulay and Mercy Otis Warren: The Revolutionary Atlantic and the Politics of Gender (2005). She lectures in English and American literature at Newcastle University.

![Fig. 1. Sarah Franklin Bache. Engraving after John Hoppner [1791] (1863). Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/7.1.Davies.1-249x300.jpg)