Reading for Relevance

Ralph Waldo Emerson was never very good at staying focused, especially on current events. Even his “Lecture on the Times” only mentions “the Banks; the Tariff; the limits of Executive Power” and other topics from the newspapers, before insisting that we should never let the news determine what is central to us in the first place. “Centrality. Centrality,” he writes in his journal—what’s the point? So in response to charges that his “reading is irrelevant,” he replies, “Yes, for you, but not for me. It makes no difference what I read. If it is irrelevant, I read it deeper. I read it until it is pertinent to me and mine, to nature and to the hour that now passes … [I] find footsteps in Grammar rules, in oyster shops, in church liturgies, in mathematics, and in solitudes and in galaxies.”

Few of us are as willing as Emerson to admit that it makes no difference what we read or that what is relevant to us or ours may exclude most everything of relevance to anyone else. Instead we have gotten in the habit of insisting on the value of relevance, especially when university funding seems increasingly to depend on external measures of utility and social consequence. Academic readers are asked to justify our function in ways that confirm our worth to the public; we calculate the long-term economic benefits of a liberal arts education, or we borrow from other fields—from cognitive science to economics and politics—whose public impacts are more tangible. Sometimes we aspire to the civic goals—”the sharpening of moral perception” or “the fashioning of an informed citizenry”—that Stanley Fish notoriously challenged in the New York Times because the humanities “cannot be justified except in relation to the pleasure they give” (though his pleasure, for him, is worth subsidizing). So while Emerson is happy to say that his interests are important for him, we say that our interests are important for the perspective they give on the emerging shape of our contemporary moment. While Emerson is satisfied with an “oblique and casual” relationship between his reading and his world, we want to believe that our reading is contingent on an aspect of the present it reveals since only from our current vantage point can the works that we read come to mean what they do.

We have gotten in the habit of insisting on the value of relevance, especially when university funding seems increasingly to depend on external measures of utility and social consequence.

In his late essay “Perpetual Forces,” Emerson describes his fondness for reading works that have survived for sufficiently long periods of time that certain properties just “adhere to them,” such as “persisting to be themselves, and the impossibility of being warped.” If these texts, for Emerson, feel less like books and more like “elemental” forces in the natural world, this is not only because their effects are so pervasive, but also because their meanings never change or yield to human “tampering.” Or as he puts it, “How we prize a good continuer!” By Emerson’s reckoning, we may need to wait another millennium or so before we can know just how much of a “continuer” he is or whether his readers will find in him the “power of persistence” (“which never loses its charm”). For now, we try our best to keep him relevant.

Emerson never appears more central than at the moment he is being read. The editors of the recent collection, New Morning: Emerson in the Twenty-first Century (2008), say their book “[underscores] the relevance of Emerson’s thought to contemporary issues as varied as the environment, race, politics, spirituality, aesthetics, and education.” An anthology from 2004, The Spiritual Emerson, promises only his writings with “the greatest relevance in today’s world.” Emerson was also timely in 1971 for the editors of Emerson’s Relevance Today, and Floyd Stovall was arguing for his relevance in 1942 in “The Value of Emerson Today.” Given that almost fifteen years have passed since Robert Richardson, in Emerson: The Mind on Fire (1996), showed the enduring “timeliness” of Emerson’s thought, it is probably just a matter of time until Emerson appears as a subject in Yale University Press’s recent series “Why X Matters,” in which each book (Why Arendt Matters, Why Poetry Matters) presents an “argument for the continuing relevance of an important person or idea.”

What does it mean to read for relevance? The urge to make Emerson relevant speaks to anxieties that shadow any discipline or institution that values the persistence of things that rarely seem to fascinate the contemporary public. Insisting on relevance may be, of course, a sign of resignation about the fate of “serious” or “deep” reading in an accelerated culture of information on-demand (see Nick Carr’s recent book, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, or Matthew Brown’s provocative discussion in this column of Sven Birkert’s The Gutenberg Elegies); but it is also the expression of a hope that any prodigal texts that feel meaningful or important to us can be brought back into the fold of the present. In the case of Emerson, such an effort may only require a little updating around the rhetorical edges of how we understand his project. At the start of World War II, Emerson is relevant as a “true exponent of democracy,” while in 1971 he matters because his ideas stand behind “the youth movement of the 1960s,” and today he is acknowledged as a champion of environmentalism and global human rights. But like any figure whose critical reception endures over long periods, the importance of accumulating relevance has little to do with “why X matters” at a given moment. In fact, Emerson’s relevance as an icon of national identity in the 1940s is probably all but irrelevant to many of his subsequent readers in the 1960s and today. Relevance is a short-lived phenomenon that must keep changing to be what it is.

Whenever we make a claim for a text’s relevance, we are not just signaling our belief in the significance of our reading, but also registering a faith in its utility and timeliness within an economy of knowledge that demands constant novelty and shifting sites of interest. Now even newspapers are finding it hard to match the pace at which all news becomes old news. Search engines employ sophisticated “relevancy algorithms” and tracking services provide real-time “Web analytics” to make sure that sites like Google News or Yahoo direct their users to the stories that are drawing the most traffic at any given instant. News aggregators or RSS feeds on Google Reader deliver continuously refreshed streams of information that have been stripped of extraneous items so that we can concentrate on what is relevant and exclude the various features (local interest stories, advice columns, classified ads) that in retrospect make newspapers appear so archaic and inefficient. The imperatives of “just-in-time” production—which responds immediately to customer demand to avoid the “waste” of inventory—have come to pattern many forms of cultural and intellectual work outside the academy and within it. We are told there is less patience, and perhaps more importantly, less money for knowledge that sits around in books, libraries or humanities departments without addressing the public’s interests now.

This may explain why Judith Halberstam worries, in a story on “The Death of English” for Inside Higher Ed, that the New York Times has stopped dispatching a reporter to the annual meeting of the Modern Language Association to write up its yearly mockery of the conference (with its “wacky” paper titles) and to savage the “sad efforts of earnest English profs to look hip, cool and vaguely relevant.” For Halberstam, we need to “update our field” or it won’t even be worth insulting, and she argues that literary scholars in particular have not “kept up” with emerging areas of focus (on empire, for example, or popular culture) that could replace traditional fields as they become “irrelevant as areas of study.” She wants her arguments to provoke and scandalize, not just to make English a vital discipline in a “rapidly changing world,” but to make sure that it stays newsworthy too: “Let’s hope that in another decade The New York Times … is forced to spend the entire year reporting in meaningful ways on the reinvigoration of the humanities.”

Is newsworthiness the same as importance? This was one of the questions posed in a lecture by Kirk Citron at the TED2010 conference in Long Beach, CA; the lecture was recently posted on TED’s (Technology, Entertainment, Design) website. Citron compares top AP stories of the past year (the “Miracle on the Hudson” plane landing and Michael Jackson’s death) with less prominent news of scientific discoveries (nanobots fighting cancer from within the bloodstream) or endemic global problems (resource scarcity in the developing world) that he thinks may be timeless enough to stay news. His point—which for the purposes of a TED lecture he communicates in a succinct, non-Emersonian three minutes—highlights the degree to which we attribute newsworthiness not to important information but to information whose relevance is just a function of our immediate interest in it. Thus relevance, as an expression of recency, crowds out almost every other factor that we could use to sort through information for what matters and what doesn’t.

The contemporary nostalgia for newspapers often trades on the idea that there was once a common set of issues that the public widely recognized as important or, as Emerson might say, relevant to you and also to me. But for many figures in Emerson’s period—who were among the first to witness our modern practices and institutions of the news take shape—the fact that newspapers had to satisfy a community of readers with divergent interests in their moment always meant that the importance of the news was in part a fiction that its currency made possible. Newsworthiness described a category of information that did not so much assert the universal relevance of some topics in respect to others, but rather answered to a restless, individualized demand for knowledge about a world already understood from the perspective of a particular and fleeting present. Indeed, we might even see the emphasis on the novelty of the news as not just its distinguishing feature for readers in nineteenth-century America, but as an expression of the foreshortened experience of temporality it promised to a democratic public that could, in fact, share almost nothing of importance besides the current events of “the Times.”

In Democracy in America (1835-40), Alexis de Tocqueville writes, “When the bonds among men cease to be solid and permanent, it is impossible to get large numbers of them to act in common … The only way to do this regularly and conveniently is through a newspaper. Only a newspaper can deposit the same thought in a thousand minds at once.” For Tocqueville, individualism is particular to democracy, a product of the disconnectedness intrinsic to a society of equals who—leaving behind the attachments and sentiments of their “caste, profession, or family”—are free to pursue their self-interests. The American way of life is by abandonment: the solitude which weighs on every individual and “[throws him] back upon himself alone” is also the cause of his restlessness. Instead of cultivating social ties whose meaning depends on staying in place and letting time give sense and continuity to the texture of civic life, Americans, Tocqueville says, are always “on the point of departure.” The “love of well-being” that has become the “national, dominant taste” means they are always chasing more wealth and pleasure and “always in a hurry”; “[grasping] at everything but [embracing] nothing,” they have no time for stable attachments and, in any case, a population which “itself changes from day to day” comes to “love change for its own sake.” So when Tocqueville writes that only newspapers can get large numbers of American to act in common “regularly and conveniently,” he suggests that what Americans have in common is the “constant need for novelty” that the daily news delivers and that the news satisfies this need in the shortest amount of time. After all, he writes, “nothing is less suited to meditation than the circumstances of a democratic society,” and newspapers are what Thoreau calls “easy reading” or “little reading”: they yield up their content to a commercial people whose “habitual inattention” (Tocqueville’s phrase)—whose habit, that is, for being unhabituated to reflection—was more conducive to consuming or digesting than to thinking.

While the promise of the news for Tocqueville is precisely its ability to bring a sense of association and common life to an isolated citizenry, he nonetheless confesses that he does “not feel toward the freedom of the press that complete and instantaneous love that one grants to things that by their very nature are supremely good.” The press may be “the most important, indeed the essential, ingredient of liberty,” where liberty is the experience and expression of individual differences on which political life—as a negotiation of differences—depends. It may at times function like the newspaper in the right corner of George Caleb Bingham’s The County Election (fig. 1), which points to a reflective immersion in the larger political drama that fills the scene. As the three men share the news, they become a model for how a disaggregated group of democrats—Whigs, farmers, gentlemen, even an Irishman in red at the top of the steps—may become a pluralistic community of voters and a deliberative audience of readers. But then, in America where, as Tocqueville says, “there is very little interest among us now in political questions” since “the entire country is busy doing business,” elections can become just “the daily grist” of newspapers for an agitated public averse to boredom. Theodore Sedgwick writes to Tocqueville about the excitements of a cheap press that sweeps all politics into a perpetual, rapid succession of mere events: “Today there is a general war in Europe, tomorrow a war in Mexico. The future of the Union is in danger and there is uproar about a poor runaway slave, and then the next day there is a financial crisis,” and so on. Maybe the civic engagement that the newspaper represents in the corner of Bingham’s picture speaks more to the way that politics have been relegated to the margins of a formless democratic society. “Politics,” Tocqueville writes in a letter to his father about the American press, “occupies only a small corner of the canvas … What space remains is monopolized by discussions of local interest, which feed public curiosity without in any way causing social turmoil.” For Tocqueville, like Habermas much later, the modern idea of the newspaper in the nineteenth century meant both the decline of a deliberative public sphere and the depoliticizing of American life; no longer a political or party organ, the newspaper’s claim to impartial and factual reporting rested on the social consensus and apathy that Tocqueville found in a shared culture of liberal individualism. If, as Kierkegaard writes, no events or ideas “catch hold of the age” and politics in the press are just “a form of sensual intoxication which flames up for a moment,” then maybe the true image of the newspaper in Bingham’s picture is the mirror image in the corner at the left: a drunken democrat imbibing spirits at a drinking table. Newspapers “offered at every corner like cheap spirits,” says Henry Ware Jr. in 1846, “are little else than poisonous stimulants.”

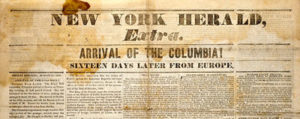

Democracy in America appeared the same year as the most successful of the early penny dailies, James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald. As media historians observe, the penny press marked a turn away (more or less gradual) from the partisan and trade papers that provided weekly content to audiences of subscribers who shared political and public interests. Now the dailies reached a mass readership that demanded information at accelerating speeds and increasingly invested in the commodity of news itself. Political and editorial comment were separated from the reporting of current events and, for the first time, the “news” became the main business of the newspaper. So when Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield Republican, writes in 1855 that the newspaper’s primary purpose is “to give the news” or when another observer writes in 1867 “that the word newspaper is the exact and complete description of the thing,” there was no redundancy since the news is what was new. “There is,” Bowles says, “a great deal more news nowadays than there used to be.”

Newspapers began to emphasize events over ideas. If in 1800 readers might find five to 20 items in a four-page paper—mostly foreign correspondence, editorials, and political essays, many running for more than a page and continuing from one issue to the next—in 1850, a four-page paper contained 35 to 40 brief items about events (since each day was now essentially eventful). “The newspapers,” writes journalist George Lunt, “bear us along with them, abreast of the rapid flood of passing events.” Papers competed with one another to produce “extras” and “late editions” that were hawked by newsboys on the streets; earlier events diminished and gave way to the succession of later events; and, after 1846, the telegraph and wire services made events seem nearly concurrent with their transmission so that the “news” meant, at the same time, the medium and the message. The press claimed to represent “The Spirit of the Age” or “The Spirit of the Times” (fig. 2) in the free and complete unfolding of information that made the newspaper, as Walt Whitman called it, the “mirror of the world.” And reading it—indeed the act of reading it suggested as a daily practice—would be nothing less (and nothing more) than a reflection of the moment one was in. One could say that the newspaper in the mid-nineteenth century aspired to the role that Hegel defined for the philosophy of history when he called it “the spirit of the age as the spirit of the present and aware of itself in thought”—except that Hegel, who worked as a reporter and editor and loved the newspaper, had made the connection himself. For Hegel, the newspaper was one way for the progress of history to reveal itself to readers every day and then for readers, in turn, to see themselves reading as part and parcel of, and relevant to, its progress. “Reading the morning paper,” he writes, “is the realist’s morning prayer. One orients one’s attitude toward the world …”

In fact Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) appeared the same month that he left the academy and took up his new post as a newspaper editor in Bamberg. We might think of the newspaper as not only the place where, in Hegel’s words, “the writing of history and the actual deeds or events of history make their appearance simultaneously,” but where “they emerge together from a common source”—the self-recording, self-narrating “spirit of the times” as it is realized in the everyday life of the newspaper. Thus as Susan Buck-Morss points out, Hegel’s devotion to newspapers speaks to the ways in which a philosophy of mind becomes the expression of the world-historical context that the newspaper manifests and records every morning. “The journalist, recording … the thing that has come to pass,” writes James Parton in 1866 about the American press, “is Providence speaking to men.” Who would want to “bury himself” in academic thought, asks Schelling in a letter to Hegel, “when the movement of his own time at every turn sweeps him up and carries him onward,” a movement that Hegel—who, as Buck-Morss describes, “never left the shores of the continent” and yet wrote a “Philosophical History of the World”—could nonetheless observe in the advances of Napoleon or the revolutions in Haiti but only by way of the press. The newspaper, Parton says, “connects each individual with the general life of mankind, and makes him part and parcel of the whole,” which is why Lunt writes in 1857 that “the newspapers bear us along with them”—to resist “may seem to some little better than rank heresy to the spirit of the age and its main instruments of thought.” If the goal of the press, according to one newspaper’s motto, was “to show the very age … its form,” then perhaps the new shape of knowledge in the age of news is the “self-consciousness” Hegel feels when he orients his attitude towards the world every morning at breakfast. At least, he says, when reading the newspaper, “one knows where one stands.”

These days it is safe to say that our contemporary attitude towards newspapers is considerably more profane than Hegel’s. Major city papers are folding, subscriptions are plummeting (fewer than 20 percent of Americans between 18 and 34 read a daily paper), and Philip Meyer predicts, in The Vanishing Newspaper, that one day in 2043 we will throw away the final edition of the last newspaper. Newspapers are marshalling resources to scale up their online enterprises and hoping that more ad revenue will follow, but some speculate these efforts are also likely to fail, and that short of funding from the government or large charitable foundations, we may need to concede with Charles M. Madigan in The Collapse of the Great American Newspaper, that “it seems, it’s just about over.” So while Judith Halberstam marks the “death of English” because the New York Times ignores us, it might be the case that English departments will outlive “the Times,” if only by a few years. (Who better to find them interesting when they have lost their relevance?)

Still, we continue to value the idea of the newspaper in terms that Hegel and the nineteenth century would appreciate: we look to the news as a “window onto the world” in hope of seeing where we stand in respect to the present it frames. So when the journalist George Flack in Henry James’s novel The Reverberator calls the newspaper “the great institution of our time” he means both that it is “the history of the age” and that it puts its readers in relation to the age so that anyone who does not keep up with the news, like the French aristocrats in the novel, also becomes unassimilable to the times the “Times” describes. The nineteenth century, in other words, learns from newspapers to read for relevance and to participate in their fantasy of perpetual currency: everything that really matters continues to speak from the perspective of the moment and stays relevant to the degree that it keeps pace with the progress of the moment. For Americans, writes Tocqueville, “the idea of the new is coupled with … the idea of the better.” To read for relevance in the nineteenth century, then—to read for relevance now—is to see things from a point of view that is more than simply presentist as we have come to know the term (a usage that itself derives from the nineteenth century) but powerfully suggests that the things we read are always the parts through which the whole of our recent culture radiantly shines through. One need only do a quick MLA title search to see how much the imperative for the “enduring relevance” of our own work (“The Enduring Relevance of Huck Finn,” “The Relevance of Thomas Jefferson for the Twentieth Century”) defines the very project of reading through the temporal logic that the age of news creates—bringing perspective to the world we are in, while bringing with it a feeling of historical synthesis that views the purpose of the past as a function of its immanent connection to us.

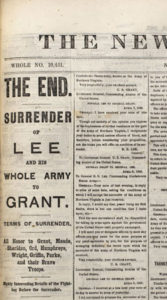

The newspaper, writes one editor, should make an effort to show “a true perspective of the world’s real developing history,” which is also why, by the mid-nineteenth century, newspapers began the practice of organizing daily events for readers within a visual hierarchy of information that suggested some things are more significant than others. As the news event became of paramount value and timeliness became the measure of its worth, the newspapers introduced a design regime that controlled the reader’s experience of the material it provided by sorting it for relevance. Headlines, new to journalism, announced the latest items and made them increasingly visible on the page (Kevin G. Barnhurst and John Nerone note that several papers in 1837 still had no headlines, but by 1847 almost all did). The division of news content into columns and digests grouped items together and prioritized some items over others within a field of information that changed each day. All items were now established with relation to the whole of the page and their respective force was due to the visual impact of headlines and subject heads in decks and banks (up to 15 banks by 1862) that often diminished in size and heaviness from the top to bottom bank (fig. 3). While newspapers often continued the tradition of placing the latest news on page two (with less timely matter on the outside pages in case ink smudged in delivery), the “extra” editions of newspapers began the practice of making the front page the symbol and expression of the news itself, so that, by the end of the century, most newspapers would look like the “extra” had looked (fig. 4). Telegraph dispatches and wire services now surpassed the mail in the timely transmission of the news and were given prominent place on the page, and the “inverted pyramid” of the news lead began to standardize the packaging of facts in descending order of importance. As Henry Justin Smith, an early editor of The Chicago Daily News writes, journalists and editors are “all artists now … They color some things so that the hasty reader can tell they are more important than others. Maybe they don’t distort facts; they do not distort so much as rearrange. They suggest perspectives … “

For Tocqueville, the problem with the news was the irresistibility of the perspective it suggested. It is not just that Americans with no time to think adopt the “ready-made opinions” of the newspaper, so that the press communicates the only picture of the world that readers will take the time to know. As a society of equals, he says, Americans “see things from the same angle” and become “naturally inclined toward analogous ideas.” “They are,” Tocqueville writes, “like travelers scattered throughout a vast forest in which all trails lead to the same spot … if they all recognize this central point and head toward it, they will imperceptibly come together without intending to.” When the individual finds himself among a democratic people who are equal and more or less alike, the newspaper becomes an instantiation of public opinion where what applies to one applies to all. In Bowles’s words, newspapers express “the whole human mind” that Americans are willing to embrace since their unwillingness to believe in difference means that they accept the view of the majority because they already believe it’s their own.

The newspaper, then, comes to represent what Tocqueville calls in Democracy in America the “association” of individuals with their age. What aligns individuals with their age—indeed what makes for the full expression of individualism in its age—is the belief that the news inspires when, as Tocqueville says, “it sweeps us up in its train” every morning: that time is dynamic and superseding and that what counts most in the shaping of public belief happened last. Relevance to the moment is the epistemological vision of democracy in an age of news where, as Tocqueville writes, the individual “must constantly rely on ideas that he has not had the leisure to delve into, so what helps him most is far more the timeliness of an idea than its rigorous accuracy” or truth. So while the press in America may be, as one editor writes, the “circulating life blood of the whole human mind,” this Hegelian figure of total synthesis between the individual, his society, and the news they share is, for Tocqueville, an altogether unwelcome sign of the times. It accounts for the skepticism we hear when he insists, for example, that “there is no advantage to any man in struggling against the spirit of his age.” A democracy of individuals reading the newspaper finally feels, says Tocqueville, like “millions of men marching at the same time towards the same point on the horizon,” which might make us think again about the medium that at least one critic calls “the horizon of men’s thoughts and sympathies.”

In his memoir, Souvenirs, Tocqueville describes the 1848 revolutions in France as a series of diminished events: the crowd, “irresistibly set in motion” and “carried away by the tide of public opinion,” had “a lot of noise but no enthusiasm.” There was “something new happening or news arriving every moment,” he says, but the agitation of the mob felt monotonous to Tocqueville because its actions, as empty repetitions of earlier revolutions of 1789 or 1830, left the mentality of society untouched. The events of 1848 represented, as Sheldon Wolin puts it, “the incessant change but homogenous sameness” of a restless modern society, in which the “frantic dash to keep pace by rejecting the past” effected little political change. “Great revolutions,” says Tocqueville famously, “will become rare,” speaking to the final conservatism of an egalitarian culture. Given Tocqueville’s sense of how the political spectacles of 1848 always “[led] to the same spot,” it is perhaps no surprise when he tells us that the revolutionaries “fed their minds on no literature but the newspapers.”

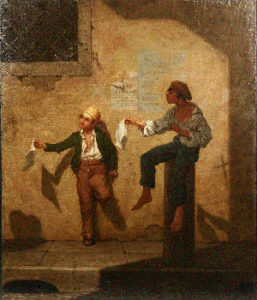

The American Martin Johnson Heade painted Roman Newsboys in the late summer or fall of 1848 during the Italian unification movement, Il Risorgimento, after republican revolutionaries had forced Pope Pius IX into exile (fig. 5). He painted it again in the summer of 1849 (fig. 6). In the first picture, two newsboys extend copies of the antipapal broadsheet, Il Don Pirlone, to an approaching figure whose shadow appears on the left. The boy in bright sunlight wears a dunce cap with “Pius IX” stitched on it, while the other boy wears a Greek cap as a symbol of the revolutionary cause. The surface of the wall is covered with graffiti about the liberation movement and the church, including a stick figure of a cardinal to the left. A poster celebrating the reformer Gioberti hangs above a poster for Roman freedom, while old perfunctory notices—or “avvisi”—peal away and fade. This is a picture of the daily news, and Heade reflects its timeliness in its topical references, but also in the idea of imminence we get from the figure who is just now emerging in his hat and from the newsboys who gesture towards him but appear frozen, as Theodore Stebbins suggests, as if by a high speed lens for us to see in the moment. We get the sense that if we were to advance the frame, the boy to the right in shadows might, in an instant, fall off his perch. Everything speaks to the sense of movement and relevance that the revolution itself inspired.

Martin Johnson Heade returned to America from a visit to Rome, where excited by the progress of the events, he chose to paint a political picture that was relevant to its times. But in 1849, the French had defeated the Roman Republic and restored the pope to power. The revolution was old news and Heade’s picture was out of date. So Heade repainted it, but now the boys hand out a newspaper with “Roma” in the title, since Il Don Pirlone had died with the republic. The revolutionary posters are nearly gone and the graffiti is wiped clean. The picture is almost the same, but there is less urgency this time and the closer newsboy has swung his leg around to the front of the post to sit more stably. He wears a regular street cap instead of a Greek cap. In the first version, the window looks into a void, but, much larger now, it is also brighter, flat and emphatically barred in a way that defies the illusion of deep space. As we look forward into a painting that seems to have lost its faith in picturing the news, our “window on the world” is blocked. The shadow from the first version has now grown longer, as if it were later in the day; the way it hangs over the newsboy is reminiscent of a gallows. A bishop’s hat encroaches from the lower right, and while there is still an imminent hat to the left, here it is old hat. The bench behind the post is gone with the extra stack of newspapers, which is to say that there are no “extras” in the version of the picture that admits its untimeliness and irrelevance and speaks more to repetition, variation and return. For Tocqueville, the mind in the age of individualism is “constantly active, but it exerts itself in endlessly varying the consequences of known principles … rather than in looking for new principles. It dances agilely in place.” We might say that Tocqueville discovers about the age what Heade discovers when he returns to his painting: that there is nothing new, only the news.

Heade never tried to be timely again. He goes from painting a pair of newsboys to painting pairs of hummingbirds, flowers, and haystacks in marshes that often resemble the newsboys formally, but have no explicit context that we can tell (fig. 7). It was not simply that he turned from the news to subjects that lack topicality and reference, but that he repeated these subjects compulsively for decades. Heade painted, for example, more than 120 versions of a northeastern salt marsh, but why move on? If one newspaper writes in 1849 that “all things seem to be hastening towards some great result,” then these are pictures that do not encourage us to look ahead, but at the sensible presence of objects that swell in the moment that we see them. “The world,” writes the paper, may be moving “towards some point at railway speed,” but in the marsh scenes our points of view are multiple and dispersed across exceedingly horizontal canvases—sometimes twice as wide as they are high. Our eyes wander the scene because there is no system of perspective in which the haystacks or streams recede to a central point on the horizon and because, unlike Hegel in front of a newspaper, it is never too clear where we stand. Without a central focus to organize their elements, these are not the sort of pictures that we “digest” easily. Heade loses perspective in the age of news and learns, in his patient commitment to the marsh, that to be untimely may actually widen our horizon and that every moment and every place he happens to be is at least relevant to him.

Further reading

Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (New York, 2010) and Sven Birkerts, The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age (London, 2006) both address the relevance of book reading within a contemporary digital culture; Alan Liu offers a more comprehensive history of the idea of information and explores possible futures for the humanities in The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information (Chicago, 2004). Kirk Citron’s TED lecture, sponsored by the non-profit group Technology, Entertainment, Design, is available here: http://www.ted.com/talks/kirk_citron_and_now_the_real_news.html. Elegies for the vanishing newspaper include Charles M. Madigan, ed., The Collapse of the Great American Newspaper (Lanham, Md., 2007) and Philip Meyer, The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism in the Information Age (Columbia, Mo., 2009). Hazel Dicken-Garcia’s Journalistic Standards in Nineteenth-Century America (Madison,Wis., 1989) provides a helpful survey of press criticism in the period. John Nerone’s article “Newspapers and the Public Sphere” in A History of the Book in America: The Industrial Book, 1840-1880, ed. Scott E. Casper, et al. (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2007) traces the modern institution of the news after the penny press, while Kevin G. Barnhurst and John Nerone in The Form of News: A History (New York, 2001) and Menaheim Blondheim in News Over the Wires: The Telegraph and the Flow of Public Information in America, 1844-1897 (Cambridge, Mass., 1994) chart how the news began to restructure and visually organize information. Susan Buck-Morss’s Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History (Pittsburgh, Pa., 2009) presents a fascinating look at the significance of Hegel’s philosophy for the age of news. Sheldon S. Wolin’s Tocqueville Between Two Worlds: The Making of a Political and Theoretical Life (Princeton, N.J., 2001) is helpful to read alongside both Democracy in America and Souvenirs. Laura Rigal’s essay in Common-Place 9.1 has a terrific account of democratic politics in Bingham’s painting. Theodore Stebbins’s The Life and Work of Martin Johnson Heade (New Haven, Conn., 2000) provides the best context for a reading of Heade’s two pictures of the newsboys.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.4 (July, 2010).

Elisa Tamarkin is associate professor of English at University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Anglophilia: Deference, Devotion, and Antebellum America (2008).