Reading with Wonder: Encounters with Moby-Dick

Upon hearing the news yearned for by every college professor—the announcement of an upcoming sabbatical leave—a senior scholar of religious studies I know celebrated his freedom by buying a fresh copy of a long-admired sacred text: Moby-Dick. Before he contemplated the research and writing he might accomplish, or outlined the diligent yet humane schedule that might structure his blissful days, he set what appeared to be a manageable goal: to have a thorough encounter with the novel whose compelling intricacies had so far managed to elude him. An hour a day spent in serene contemplation of Melville’s prose, feet propped on the ottoman, cup of tea at hand, seemed the humanist’s reward for years of labor. The novel, it seems, had other plans.

Burnt out, frustrated, and bored after thirty chapters, this professional reader could not finish the book.

What had gone wrong? Surely it was his fault. Perhaps it was some innate deficiency: a previously asymptomatic and probably imaginary tin ear for great works of literature. It might well have been the book’s “Cetology” chapter: that bugbear of a whale catalogue whose painstaking detail has repelled generations of undergraduate readers, sending them back to their CliffsNotes. At the very least, this scholar suddenly appreciated the challenge of pursuing such a major literary project on his own without the motivating presence of colleagues or students, whose anticipated questions often push us through our most difficult texts.

But was this failed encounter with Moby-Dick the reader’s fault, or the book’s? Why did this literary experience promise so much, and then refuse to deliver? Even more curiously, was there anything that this reader might have learned in the midst of this endeavor that might eventually be of greater value than a successful reading of the book itself?

Many of us labor under the impression that Moby-Dick is a book we should read and, more importantly, understand. An avatar of the “Great American Novel,” as elusive a concept for writers and critics as the White Whale is for Ahab, the book both tantalizes us and makes us feel uninformed if we have not yet turned its pages. Those who were not exposed to the book in their high school or college years may be slightly embarrassed; Moby-Dick may be on others’ bucket lists as they dream of continuing their education in retirement. Yet Moby-Dick is familiar territory to most of us. We may have read excerpts from the novel in American literature anthologies, all the while absorbing the message that The Scarlet Letter is certainly legible in full, whereas Moby-Dick is not. The central drama of Melville’s book seeps into popular culture, and often supplies the animating metaphor in political debates about American imperialism, exceptionalism, and assertions of global morality. Ahab has reappeared alternately as Al Gore fighting for disappearing votes in Florida, one of the two Presidents Bush in pursuit of embodied “evil,” or a monomaniacal hedge-fund manager in search of the ultimate rate of return. The ghostly cultural presence of Moby-Dick might persuade us that Ahab is the narrative’s central figure, and that his quest for revenge is the only story that the novel has to tell.

To the reader who actually commits to opening the book, Moby-Dick offers an entirely different story: the journey of Ishmael. Melville’s narrator is the one who encourages us to address him as a friend before ushering us into the “wonder-world” of whaling, and who makes those promises on which the narrative fails to deliver. It is he who essentially creates Ahab, and he to whom we as readers must pay more attention. Ishmael gets our hopes up from the start. Have you not felt the thrill of that “mystical vibration,” he asks, or experienced the revelatory confluence of “meditation and water” that a sea voyage holds? His questions are maddeningly suggestive. What will happen on this adventure? “Surely all this is not without meaning,” he assures the reader, as he evokes “the image of the ungraspable phantom of life” that will be “the key to it all.” After such an opening, who could not hope to find an explanation of the meaning of life itself in this novel’s pages?

There are some early warning signs that we as readers may not receive what has been promised to us. Even as Ishmael sparks the reader’s curiosity with a vision of “a portentous and mysterious monster” floating in “wild and distant seas,” not to mention other “attending marvels” of his voyage (the kind of exotic itinerary to which the readers of Melville’s highly successful early adventure novels, Typee, Mardi, and Omoo, had become accustomed), he confesses his limited understanding of his own story. Ishmael explains, “I think I can see a little into the springs and motives which being cunningly presented to me under various disguises, induced me to set about performing the part I did, besides cajoling me into the delusion that it was a choice resulting from my own unbiased freewill and judgment.” Weighed down with qualifiers (“I think I can,” “a little”) and uncertain in its intent (obscured by “disguise” and “delusion”), the statement provides readers with a clue that this narrator may not fully comprehend the events of his own life, or know how to retell that story so that it makes sense to others. We are already in trouble.

Ishmael, as it turns out, is cripplingly naïve. When he enters this new “wonder-world,” he misinterprets nearly every sign and character he encounters. When Peter Coffin, the landlord of New Bedford’s Spouter-Inn, tries to explain to him why his mysterious suitemate, the Pacific Islander Queequeg, has not yet returned to the inn, Ishmael works himself into “a towering rage,” exclaiming, “Can’t sell his head?—What sort of a bamboozling story is this you are telling me?” Without the cosmopolitan reference points that other sailors possess, Ishmael fails to realize that Coffin is not mocking his ignorance, but rather speaking of Queequeg’s shrunken head, nor can he tell that another hotel proprietor really means to give him a choice between two kinds of chowder when she offers him one measly “clam for supper.” As Ishmael misses these verbal cues, readers are plunged into the same confusion that he feels; we are at sea even before the Pequod‘s voyage begins.

The novel actually intends for us to share Ishmael’s disorientation; his interpretive challenges therefore become our own. His arrival at the Spouter-Inn plays out in the second person, as not only he, but now “you found yourself” in the entry hall of the inn, looking at a particularly baffling painting. As “you” (the reader) and Ishmael contemplate this picture together, you begin to understand why reading the novel itself might be such a challenging proposition. Ishmael observes:

On one side hung a very large oil-painting so thoroughly besmoked, and every way defaced, that in the unequal cross-lights by which you viewed it, it was only by diligent study and a series of systematic visits to it, and careful inquiry of the neighbors, that you could any way arrive at an understanding of its purpose. Such unaccountable masses of shades and shadows, that at first you almost thought some ambitious young artist, in the time of the New England hags, had endeavored to delineate chaos bewitched. But by dint of much and earnest contemplation, and oft repeated ponderings, and especially by throwing open the little window towards the back of the entry, you at last came to the conclusion that such an idea, however wild, might not be altogether unwarranted.

The painting, like the book, is obscure and difficult. It requires “diligent study” and intellectual exertion, and it cannot be understood on the first try. Along with Ishmael, we must ponder this painting in “a series of systematic visits” or multiple readings, and we cannot do it alone: we also must ask for help from our “neighbors,” friends, and fellow readers who are likely to share our baffled frustration.

As I tell my students, Moby-Dick is the ideal text to read together in a discussion seminar, a group that can share the burden of interpretation and illuminate the book’s mysteries from different angles. But woe to the solitary reader who finds herself stymied in an effort to discern the narrative’s ultimate “purpose.” The novel celebrates this kind of sociability as it chronicles events like the “Gam”: a floating gathering of whaling ships that relieves the isolation of months or years at sea. In fact, one of the key experiences that persuaded me to give the previously impenetrable Moby-Dick another try was a “Gam” of sorts held by a group of professors and students in my graduate program: a meeting of landlocked readers who found certain elements of the novel fascinating, but realized that they would come to a much better understanding of the book as a whole in conversation with others. No wonder Ishmael insists on our fellowship in this work of interpretation.

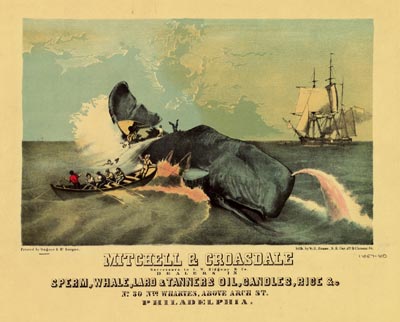

What puzzles him the most is the actual subject of the painting. Later on, Ishmael will realize that instead of “chaos bewitched,” his first but nonetheless startlingly accurate impression, the painting depicts a ship about to be destroyed by a giant “exasperated whale.” Our minds do not have to leap very far to recognize this as a version of the Pequod‘s fate: this is one of many portholes through which the novel foreshadows its narrative conclusion. In the end, however, locating the whale underneath all the layers of accumulated grime that “besmoke” this picture isn’t the point. The process of guesswork is far more interesting. Ishmael tells us that this is “[a] boggy, soggy, squitchy picture truly, enough to drive a nervous man distracted. Yet there was a sort of half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it, till you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvelous painting meant.” Despite, or more likely because of its “squitchy” nature, the book inspires in us a feeling of wonder, a desire for knowledge. You as a reader are compelled to “find out” more, simply because the meaning that this book promises is so sublime. Although that meaning may be only “half-attained,” or even “unimaginable,” it hovers right on what Philip Fisher calls “the horizon line of what is potentially knowable, but not yet known”: that territory we want desperately to inhabit but know we cannot quite reach.

Frustrating, teasing, and egging us on as we swear to ourselves that we will master, or at the very least, finish this book are all part of Melville’s larger plan. In “Hawthorne and His Mosses,” the 1850 review of his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short fiction that served as a platform to discuss his own theory of writing, Melville shares his secret. What is most admirable about an author like Shakespeare, he explains, is the way in which his lines evoke “that undeveloped, (and sometimes undevelopable) yet dimly-discernable greatness” of a working imagination. This imagination captures “occasional flashings-forth of the intuitive Truth” that, however fleeting, keep spectators and readers alike hooked as they balance on the edge between the known and the unknown. For Melville, a writer’s power to suggest an elusive “Truth,” whatever that may be, is far more important than his capacity to explain what that meaning really is. As readers of Moby-Dick, a book of distinctly Shakespearean ambition, we are perplexed by the holes that riddle the narrative even as we endeavor to see through them to the ultimate truth we have been promised.

As the story works toward its final scene of deadly encounter between Moby-Dick and the Pequod, Ishmael, and consequently the novel’s readers, get distracted by a number of fascinating but oddly unrelated pursuits. In the midst of the voyage that Ahab commands with frightening resolve (“Naught’s an obstacle, naught’s an angle to the iron way!”), Ishmael cannot stop playing around. In what other nineteenth-century novel would you find such a clash of high-mindedness and lowbrow humor? The narrative swings wildly from monologues that would be more at home in a tragic drama to a song and dance scene straight out of musical theater, from Biblical reflections on the story of Jonah and the whale to a sacrilegious costume party in which a fellow sailor dresses up in the foreskin of a whale and becomes a candidate, as Ishmael winkingly informs us, for an “archbishoprick.” The novel is fundamentally strange and endearingly nerdy, as students often delight in observing, with its pages of epigraphs, its jokes about “Sub-Sub librarians,” and its leaden footnotes. It explores different types of language and various registers of meaning, from those vague questions of fate and free will that haunt the narrative from the beginning, to the symbolic potential of the color white, to the detailed cultural history of the “curious substance” called ambergris that is extracted from whales. Unlike such contemporary novels as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, whose lines of narrative intent were consistent to a fault, Moby-Dick never would have survived serialization, as each chapter seems like an independent essay or perhaps a novel in miniature. Even when those disparate parts are bound together along the spine of a book, readers must constantly readjust their expectations of the text lest they lose their footing in the midst of its literary storm.

So what are we to make of Moby-Dick, that book which New York editor Evert Duyckinck pronounced in his review “an intellectual chowder of romance, philosophy, natural history, fine writing, good feeling, [and] bad sayings”? Ishmael, who has endeavored throughout the narrative to piece together the different components of a whale, has left us holding its parts without comprehending the whole. He studies each body part of the whale carefully, devoting entire chapters to the skin, the blubber, the head, the sperm, the brain, the spout, and finally, the tail. When he reaches the end of this catalogue, Ishmael stops, apparently defeated. He tells us:

The more I consider this mighty tail, the more do I deplore my inability to express it. At times there are gestures in it, which, though they would well grace the hand of man, remain wholly inexplicable… Dissect him how I may, then, I but go skin deep; I know him not, and never will. But if I know not even the tail of this whale, how understand his head? much more, how comprehend his face, when face he has none? Thou shalt see my back parts, my tail, he seems to say, but my face shall not be seen. But I cannot completely make out his back parts; and hint what he will about his face, I say again he has no face.

The whale’s “tail” in this passage illuminates something crucial about the “tale” of the whale that Ishmael himself tells. Not only does he sense his “inability to express” its essence in writing, a narrative deficiency that has been clear from the beginning of the story, that very essence is itself “inexplicable.” Both the tail and the tale have “no face”: they perpetually elude the reader bent on their pursuit, and cannot be met head on. Ishmael’s invocation of the Biblical language of the Old Testament in this moment—in particular, the prophet Jeremiah’s portrayal of divinity as that ineffable presence with no discernable face—speaks to the limits of human understanding that Melville seeks to explore.

When Ishmael realizes that he cannot comprehend the whale’s tail, his wonder returns, and the cycle of questioning and knowing the world begins again. In this moment of failure, even intellectual disaster, Ishmael grasps the humility that eludes Ahab even more definitively than Moby Dick himself. Unlike Ishmael, Ahab is confident that he knows the whale and follows a stubbornly straight line to locate him, all the while proclaiming “[t]hat inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate.”

As a narrator, Ishmael fails us. He admits as much, noting as he constructs his ambitiously comprehensive system of cetology that “any human thing supposed to be complete, must infallibly be faulty.” Yet, he is the only one who survives the wreck of the Pequod, and the only one who has a chance to tell this tale. In the novel’s paradoxical terms, his failure is actually the key to his success.

To a certain extent, Moby-Dick rewards those readers who make it to the bitter end with the Pequod and her crew. The novel’s final chapters chronicle three days of a climactic chase: the Hollywood-style action sequence that we have been waiting for all along. For those who have made their way through the preceding 130-odd chapters, though, it might seem that the real energy of the book lies elsewhere: in that middle ground where Ishmael’s meditations meet our own exasperated efforts to comprehend the novel’s intentions. When we as readers fail in our encounters with this book, whether that means we never complete it or never feel like we fully understand it even if we read every chapter, we have seized, perhaps by accident, upon its uniquely counterintuitive truth. If you have never managed to finish Moby-Dick, you may actually be wiser than you think.

Further Reading:

An excellent edition of Moby-Dick with sections on Melville’s sources and reviews is published by Norton (New York, 2002). On the sea narrative tradition, see Hester Blum, The View from the Masthead: Maritime Imagination and Antebellum American Sea Narratives (Chapel Hill, 2008), reviewed in Common-place 9:3 (April 2009). For more on the historical context in which Melville wrote Moby-Dick, as well as the resurgence of its themes and characters in contemporary American culture, see Andrew Delbanco, Melville: His World and Work (New York, 2006). For a consideration of Moby-Dick as a “Great American Novel,” see Lawrence Buell, “The Unkillable Dream of the Great American Novel: Moby-Dick as Test Case,” American Literary History 20:1-2 (2008). Passionate readers may be especially intrigued by the discussion of wonder in Philip Fisher, The Vehement Passions (Princeton, 2002).

This article originally appeared in issue 10.2 (January, 2010).

Leslie Eckel is assistant professor of English at Suffolk University in Boston. She is completing a book on Transatlantic Professionalism: Nineteenth-Century American Writers at Work in the World and contemplating a reader’s guide to Moby-Dick.