Reading and Writing Indians

Native American literacy in colonial New England

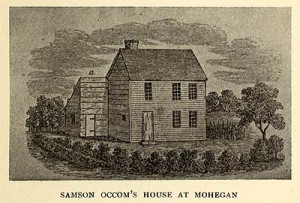

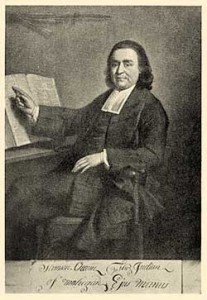

Samson Occom—Mohegan, Presbyterian minister, and Native political leader (1723-1791)—was a famous man, so famous that even in his absence strangers were introduced into his house so that they could marvel at his accomplishments and his urbanity, as we learn from the journal of an obscure eighteenth-century Quaker named Abner Brownell (now in the AAS diary collection). Describing his travels in the year 1779 throughout New England and upstate New York, Brownell recorded his near encounter with Occom. As it happened, Occom was not home at the time of Brownell’s visit, but Brownell left us a most intriguing view of reading and writing in this Mohegan community. His Mohegan guides conducted Brownell through Occom’s house to his book collection.

he appear’d (as they told me) to be a man of great Litteral Learning; I saw his Study, being a Stow Room in his Chamber, where his Library of books was in which was as we Judg’d about a Common Cart-body full, being books of all Sorts Some of all the Languages that is often Learnt in this Nation, of which they told me he understood and many upon Divinity being of all Sorts, and of all Societys Setting out that are in this Nation and also having as Large Volumes of Comments and Expositions and Annotations of the bible as I Ever saw or heard of in these parts.

Awed by Occom’s erudition, Brownell could only measure the importance of the books by their quantity (“a common cart-body full”) and by the fact that Occom’s texts were in languages other than English. He emphasized that Occom was a towering figure of scholarly sophistication “in this Nation,” comparable to any other learned gentleman “in these parts.” It is worth noting too that even though Brownell passed through the Mohegan area repeatedly in his later travels he never returned to find Occom himself at home. It seems that seeing Occom’s library was more than enough for Brownell to “read” and understand Samson Occom.

A speaker of multiple languages, a gifted writer, a voracious reader, and a widely respected community leader, Samson Occom taught himself to read and write during his teenage years. In 1743, he sought out the help of the local white minister Eleazar Wheelock to further expand his education. Wheelock’s work with this extraordinary young man (who by his twenties had mastered Greek, Latin, Hebrew, as well as English, in addition to his native Mohegan language) convinced the minister to open Moor’s Indian Charity School for Native and white charity students in 1754. In 1765, Occom left his post as a minister and schoolteacher among the Montaukett tribe of Long Island to embark on a two-year journey to England to help finance Wheelock’s school, which he saw as a promising opportunity for Native people. By the time of his return, however, he and his mentor Wheelock had a bitter falling out over the use of the funds Occom had worked so hard to collect and over Wheelock’s desire to shift the direction of his school from educating Native students to serving as a college for white students. Severing his ties with Wheelock, Occom dedicated himself to the founding of Brotherton, a new kind of a pan-tribal Christian community in upstate New York.

Eleazar Wheelock too was gloomy about the outcome of his educational venture. In 1771, he assessed that of the forty or so Native students who “were sufficiently masters of English grammar, arithmetic, and a number of them considerably advanced in the knowledge of Greek and Latin, and one of them carried through college,” “I don’t hear of more than half who have preserved their characters unstain’d, either by a course of intemperance or uncleanness, or both; and some who on account of their parts, and learning, bid the fairest for usefulness, are sunk down into as low, savage, and brutish a manner of living as they were in before any endeavours were used with them to raise them up.” Wheelock felt that most of his students (besides the exceptional Samson Occom) had failed him. And he viewed the failure of his school as the general failure of Native literacy in New England.

But Wheelock’s claim simply wasn’t true. After all, in addition to Occom, his school produced Indian writers like David Fowler (Montaukett) and Joseph Johnson (Mohegan) and an extraordinary collection of letters and accounts by various Native students, girls as well as boys. Even so, official missionary pronouncements like Wheelock’s on the general inadequacy of Native peoples to become properly “civilized” have fostered the assumption that Native Americans remained outside of the vibrant eighteenth-century world of reading, writing, and print culture. But if we turn to newly uncovered sources (and view old sources with fresh eyes) we can glimpse a more nuanced picture of literacy in the daily lives of Native people.

In fact, we don’t even have to leave the Occom household to begin to expand our understanding of how Native people related to books and writing. Mary Occom, wife of the famous minister, was surely at home when Brownell visited and was ushered into Occom’s study, which, remember, was “a Stow Room” off their “chamber.” What were her thoughts as this group of men tramped through her bedroom to marvel at her (absent) husband’s erudition? Did any of her visitors wonder whether she could read and write? (Brownell does not even mention her in his account.) Mary Occom did not own “a common cart-body full” of books, and she most certainly did not have her own room for reading and writing. But on her husband’s two-year trip to England years earlier she had exchanged letters with him. Her household accounts for the period of his extended absence include money spent on an inkpot, powder, and paper, surely the most tangible clue to her own literacy. Raising small children during her husband’s long absence in the same house that later came to stand in for her husband’s extraordinary readerly and writerly achievement, how lonely and overwhelmed Mary Occom must have felt mixing her own ink and penning her own letters at the kitchen table in the very few moments of quiet she could find for herself. It is not surprising that Samson Occom described letters from his wife during this time as “chiefly mournful.” None of these letters survive.

Letters that do survive show that Native families relied upon correspondence to maintain their connections to each other as they became increasingly dispersed for work or through marriage. These letters are extraordinary only for their very ordinariness. In 1763, Sarah Wyoggs fills in her brother (Samson Occom) on family news: “Brother Jonathan has had a long fit of sickness this summer … your mother is well at present, & Lucy & her family, only the youngest Child is frequently sickly, Thomas went up to Windsor last winter, came down last march & after tarr[y]ing a few days … he returned to his wife. As for myself I am as well as I am ordinarly … ” “Pray mother to bring my cotton yarn, and [a] bit [of] Red broadcloath to back my old Cloak,” asks Olive, Mary Occom’s grown daughter who writes to her parents shortly after marrying and moving to a different town in 1777. (Both letters are from the collections of the Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.)

Other surviving forms of Native writing include diaries, sermons, and biographical accounts. There are also wills and other more or less informal documents like land deeds and records of other kinds of economic exchanges between individuals. Native writers copied out music books called gamuts as well as other kinds of print texts to make them more widely available. They also kept various kinds of “accounts,” an all-encompassing category ranging from grocery lists and records of household finances to travel descriptions and narratives. Some wrote government petitions. Many dictated their thoughts and concerns to others who wrote those words for them. One of Wheelock’s students, a young Delaware man named Hezekiah Calvin, even forged a pass for a slave, an act that landed Calvin in jail and caused Wheelock (himself a slave owner) much embarrassment. After all, this was hardly the way he had envisioned his students using their literacy skills.

Truth be told, even though Wheelock was eager to accept the credit for the achievements of extraordinary students like Samson Occom, his school was by no means the only way Native New Englanders became literate. Throughout New England, indenture contracts required that Indian servants be taught to read, and increasingly through the eighteenth century those contracts even specified that they be taught to write. While the vast majority of such contractual obligations were not fulfilled, enough were that there were increasing numbers of Native readers and even writers in early America. In fact, Wheelock’s school was intended to capitalize on an already expanding interest among Native people in reading and writing. New England tribes had been funding their own schoolmasters on and off for decades by the time Wheelock founded Moor’s Indian Charity School.

Missionary Experience Mayhew’s account of conversions on Martha’s Vineyard, Indian Converts, Or, Some Account of the Lives and Dying Speeches of a Considerable Number of the Christianized Indians of Martha’s Vineyard in New England (1727), shows that many Native people easily and comfortably used their literacy skills daily and, in fact, had been doing so for two generations. According to Mayhew, the Bible was the primary text for Native readers. In this way, Native Americans were no different from most colonists of the period, religious or not, who learned to read in the pages of the Bible and viewed it as the central text of literate experience.

Even a handful of surviving criminal confessions by Native Americans contain some markers of Indian reading and writing practices. Katherine Garrett, a Pequot woman convicted of infanticide in 1738, spent six months in jail in New London, Connecticut, awaiting her execution. At her execution, she said that she was “grateful” for this additional time she spent “reading the holy Scriptures and other good Books that were put in her hands.” In fact, her course of reading was viewed as evidence that Garrett had repented and converted to Christianity, and she was consequently permitted to receive visitors and even visit friends and fellow Christians throughout New London during her incarceration. Garrett’s own account of her life, which she may have written herself, appears as an appendix to the published edition of an execution sermon delivered by Eliphalet Adams, who was with Garrett on the scaffold.

In addition to “godly books,” we know from diaries and other sources that Natives were eager consumers of the kinds of print ephemera that circulated throughout New England. Newspapers, broadsheets, and almanacs were cheap, widely distributed, and easily available; newspapers and broadsheets were usually passed from individual to individual, while almanacs were individually owned, marked up, and consulted for everything from the weather to circuit court dates. Works like Samson Occom’s sermon were read out loud in community gatherings, as were letters of general interest and news reports.

And this is where the distinction between oral and literate culture becomes less clear. Native people gathered together to meet visitors, pray together, celebrate, grieve, and maintain their connections as communities in countless ways. In these moments, texts—printed sermons, prayer books, hymnals, letters, and petitions—were read out loud, to be discussed or understood communally. Even though only some Native people were readers or writers, all could hear reports read out in community gatherings and have their words written out for them by an accommodating friend or neighbor, making the distinction between literate and nonliterate seem largely beside the point. From criminal confessions to missionary celebrations, from personal diaries and letters to court documents, such seemingly unrelated materials make us see with new eyes what had already been available through our print archive: one way or another, regardless of whether any particular individual could read or write, Native communities in New England were alive with texts.

Further Reading:

Joanna Brooks, The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan: Leadership and Literature in Eighteenth-Century Native America (New York, 2006); Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (Minneapolis, 2008); Kris Bross and Hilary Wyss, Early Native Literacies in New England: A Documentary and Critical Anthology (Amherst, Mass., 2008); Laura Arnold Liebman, Experience Mayhew’s Indian Converts: A Cultural Edition (Amherst, Mass., 2008); William DeLoss Love, Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England (reissued, Syracuse, N.Y., 2000); James Dow McCallum, Letters of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indians (Hanover, N.H., 1932); Laura J. Murray, To Do Good to My Indian Brethren: The Writings of Joseph Johnson, 1751-1776 (Amherst, Mass., 1998); Hilary E. Wyss, Writing Indians: Literacy, Christianity, and Native Community in Early America (Amherst, Mass., 2000).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.3 (April, 2009).

Hilary E. Wyss is the Hargis Associate Professor of American Literature at Auburn University. She is the author of Writing Indians: Literacy, Christianity, and Native Community in Early America (2000), and, with Kristina Bross, Early Native Literacies in New England: a Documentary and Critical Anthology (2008). Her current book project, titled “English Letters: Native American Literacies, 1750-1850” is a study of Native American educational practices in the colonial and early national period.