Reconstructing a Lost Library: George Wythe’s “legacie” to President Thomas Jefferson

It may not be a terribly exciting manuscript aesthetically, but a list of books in Thomas Jefferson’s hand, identified 12 months ago at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS), sheds new light on an important episode in the intellectual history of the early American republic: George Wythe’s 1806 bequest of his sizable library to President Jefferson. A prominent jurist and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, Wythe was Jefferson’s law tutor in Williamsburg during the 1760s, and his “most affectionate friend through life.”

Why is this list of books noteworthy? Jefferson’s library, which he sold to Congress in 1815 following the destruction of the Congressional library by the British in the War of 1812, is arguably one of America’s national treasures. This collection, which Jefferson described in 1814 as having been 50 years in the making, and on which he “spared no pains, opportunity or expence to make it what it is,” formed the foundation of the Library of Congress as we know it today. The newly discovered list enables us to identify the Wythe books within Jefferson’s library. It greatly expands our understanding of Wythe’s book collection, its contents and the ideas they represented, as well as its disposition following his untimely death. For Jefferson scholars, it sheds new light on America’s third president as a book collector. Jefferson documented his collection decisions in this manuscript—which books to retain, which ones to give away, and to whom. For scholars interested in book history, this previously unknown primary source provides a fascinating case study on provenance, as we trace books as objects moving from one collection to another, both geographically and over time.

Our story begins when Endrina Tay, a librarian working at Monticello, asked to examine Jefferson’s “1783 Catalog,” a manuscript book catalog that Jefferson maintained from the late 1770s through 1812, now preserved in MHS’s Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts. Although Tay has worked on the Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries Project at Monticello since 2004, she had used only digital images of the 1783 Catalog, and had never seen the President’s original manuscript list. (The Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries project is building a comprehensive and publicly accessible database of the books Jefferson owned, read or recommended throughout his lifetime. It is now part of the Libraries of Early America project on LibraryThing.com.)

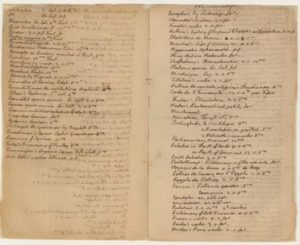

When MHS’s assistant reference librarian, Jeremy Dibbell, brought out the clamshell box containing this manuscript, we were both surprised to find a second, untitled list in Jefferson’s distinctive hand. This list consisted of three folded sheets, forming twelve pages (eight written, four blank). The first five pages contained short lists of books grouped under the names of some of Jefferson’s family members and other individuals. The final three pages listed additional books, bracketed with subject headings similar to those used by Jefferson in organizing his library, such as Common Law, Mathematics, and Architecture. Neither of us recognized this list, and there was nothing in the collection’s online finding guide or other files identifying it.

Coincidentally, Tay had recently answered a reference question about Jefferson’s ownership of Wythe’s books, and the knowledge that Jefferson had given some away was fresh in her mind. Could the unidentified list be an inventory of the books Jefferson had received from Wythe?

This question set us on a lengthy but exhilarating investigation, which led from published bibliographies, through Jefferson’s correspondence at MHS and the Library of Congress, and into library and auction catalogs and several estate inventories. Our first foray was to examine the mystery list for known Wythe titles: books still in existence, containing Wythe’s bookplate, signature, or notes. Most of these titles are at the Library of Congress, scattered among the remains of the collection Jefferson sold to Congress in 1815. E. Millicent Sowerby’s five-volume bibliography of Jefferson’s collection, published between 1952 to1959, includes thirty-one books identified as likely to have originated from Wythe’s library. Remarkably, twenty-four of these appear in the final three pages of the untitled booklist. The placement of these entries towards the end of Jefferson’s 1783 Catalog suggested that he added them at some point after the majority of entries were made, a detail consistent with their relatively late acquisition in 1806.

The chances that such a high rate of overlap could be coincidental seemed tiny, and Dibbell emailed Tay: “I think we may just have it!” Still, much sleuthing remained. We were now convinced that the final three pages of the untitled list represented books retained by Jefferson. This suggested that the preceding five pages listed books that he gave away.

James Dinsmore, an Irish joiner who worked at Monticello from 1798 through 1809, received seven books, among them the 1762 edition of The Antiquities of Athens by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett. James Ogilvie, tutor to Jefferson’s grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph, received two volumes of Etienne Bézout’s Cours de mathematics, à l’usage du corps royal de I’artillerie, plus a nine-volume edition of Cicero, which he recalled in his 1816 memoir (Philosophical Essays) as “a complete and elegant edition in quarto.”

Other recipients of a few Wythe books included Jefferson’s granddaughters, Ann Cary Randolph and Ellen Wayles Randolph; his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph; and his son-in-law, John Wayles Eppes (previously married to Jefferson’s daughter, Maria, who died in 1804). Ann and Ellen (aged fifteen and almost ten respectively) were given works by Plutarch, Dryden, and Shakespeare, along with Alexander Pope’s translations of the works of Homer. Martha received a nine-volume set of Pope’s works, and to Eppes went a collection of classical texts, including the Foulis editions of Herodotus, Xenophon, Caesar, Homer, and Cicero.

Jefferson’s favorite grandson and namesake, fourteen-year-old Thomas Jefferson Randolph, received a significant number of books, comprising two full pages of the list: seventy-two titles in 111 volumes. These books, including classical texts in the original languages and in translation, histories, and works on mathematics and grammar, would have been seen by Jefferson as an integral part of his grandson’s education, in which he took a great interest. One of the Wythe books given to young Randolph, the first volume of Hugh Blair’s Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Letters (Philadelphia, 1784), was sold at a 1921 auction, described as bearing the “autograph of T. J. Randolph on title.”

Another full page of the list was devoted to books given to Thomas Mann Randolph, husband of Jefferson’s daughter Martha. Jefferson wrote Randolph on October 10, 1806, that he had boxes of books for him; these may have included those designated for the entire Randolph family. Thomas Mann Randolph’s 1832 estate inventory includes all but six of the titles noted on the list. There is some overlap between this probate inventory and the books given to young Thomas Jefferson Randolph, suggesting that a few of the books Jefferson designated for his grandchildren may have found their way into their father’s library.

The first group of books on the list proved most challenging to trace. The top edge of the first page is missing, eliminating any name or other information. Fortunately, we were able to trace some titles in this section. Mostly standard law reports and texts, they went to Dabney Carr, Jr., Jefferson’s nephew and an up-and-coming lawyer, appointed commonwealth’s attorney for Albemarle County in 1801. A September 11, 1806, letter bears out our finding: “Th. Jefferson with his affectionate salutations to Mr. Carr, sends for his acceptance some books, a part of Mr. Wythe’s law library, which may be useful to him in his law-labors. in this disposition of them he believes he fulfills the philanthropic views of the testator more exactly than by retaining them himself.” We located three books from Carr’s collection that matched titles in the first section of the mystery list. Matthew Hale’s Historia placitorum coronel (1736), at the University of Virginia, contains an inscription, “Given by Thos Jefferson to D Carr 1806.” Sir Geoffrey Gilbert’s Reports of Cases in Equity (1742), also at the University of Virginia, contains a similar note. And in the 1875 auction of the library of Richmond judge Thomas Wynne, we found a copy of Lord Raymond’s British law reports (1743), which had passed from Wythe to Jefferson to Carr and later to Wynne.

With clues gleaned from Jefferson’s correspondence, we were able to put together a timeline of events leading up to the creation of this book inventory. In January 1806, Wythe added a codicil to his 1803 will: “I give my books and small philosophical apparatus to Thomas Jefferson, president of the united states of America; a legacie considered abstractlie perhaps not deserving a place in his musaeum, but, estimated by my good will to him, the most valuable to him of any thing which i have power to bestow.”

On June 12, 1806, Jefferson received a letter from William DuVal, Wythe’s executor, informing him of Wythe’s tragic death on June 8. Wythe’s ne’er do well grandnephew, George Wythe Sweeney, had allegedly forged checks to pay gambling debts and then resorted to poisoning both Wythe and Wythe’s fifteen-year-old former slave, Michael Brown, who was to have inherited a portion of Wythe’s estate. Brown did not survive, but Wythe lived long enough to disinherit Sweeney (who was later acquitted of the murders).

On July 12, DuVal informed Jefferson that “A catalogue of the Books, the Small Phylosophical Apparatus, with the two Cups and Gold headed Cane, also Mr. Wythe’s portrait” had been delivered to the care of George Jefferson, the president’s cousin and designated agent in Richmond. DuVal added: “The Terrestrial Globe is missing. It is apprehended G.W.S. [George Wythe Sweeney] sold it. He sent last year several Books belonging to Mr. Wythe to vendue.” Sweeney had a history of financing his debts by stealing his granduncle’s property, including selling three trunks of Wythe’s law books. Sometime between August 17 and 30, Wythe’s library, packed in five boxes, arrived by wagon at Monticello together with Wythe’s portrait. The book catalogue mentioned by DuVal arrived with Wythe’s books but has never been found.

Jefferson spent the month of September 1806 at Monticello, minding the affairs of state remotely; and also at Poplar Forest, building the foundation of his retirement retreat and overseeing his tobacco farm. He also took time to inventory Wythe’s books. A consummate list maker, he compared the titles he received against his own library catalog and created an inventory of the titles he decided to retain and the duplicate titles he would offer to relatives and other individuals. The result of this effort is the list housed in the Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts at the Massachusetts Historical Society, now recognized for the first time in over a hundred years.

The previous attempt to recreate Wythe’s library, undertaken by Barbara C. Dean at Colonial Williamsburg in 1975, identified just 170 titles (some based on conjecture). The new list more than doubles that count, revealing that Wythe’s bequest to Jefferson amounted to some 338 titles in 649 volumes. Of those, Jefferson gave away 183 titles in 400 volumes, and retained 155 titles in 249 volumes.

Jefferson had a practice of marking his books by placing his initials, “T” before the first I-quire signature and “I” after the T-quire signature. Signatures are printer’s marks, often alphabets or numbers printed at the bottom of page gatherings or quires, to ensure that bookbinders assembled the page gatherings in the correct order. We noticed that Jefferson did not generally place his initials in the Wythe-Jefferson books extant at the Library of Congress. Was this omission out of respect for his mentor? Or was it simply because he lacked the time for this task during those few weeks at Monticello in September 1806? These are among the questions that continue to intrigue us.

Digital images of the booklist are available through the Massachusetts Historical Society’s Jefferson Electronic Archive, and a transcription of the list, with links to the digital images is also online. The full annotated catalog of George Wythe’s library is available on LibraryThing.com as part of the ongoing Libraries of Early America project. We hope that scholars will take advantage of these resources in their studies of the lives and works of Jefferson, Wythe, and others, and that this list will also be useful in future scholarship relating to book history and print culture in the early republic.

Further Reading

Jefferson’s 1783 Catalog and his correspondence with Dabney Carr Jr., Thomas Mann Randolph, and George Jefferson are all in the Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society. His correspondence with William DuVal is in the Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress, and available online. Thomas Mann Randolph’s probate inventory is found in Albemarle County Will Book XI: 346-349. James Ogilvie’s memoir is Philosophical Essays (Philadelphia, 1816). The auction record for Hugh Blair’s Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Letters is lot 16, Selections from the Purchases and Stock of the Late George D. Smith [Part Three] (New York: Anderson Galleries, 1921). The auction record for Lord Raymond’s reports is lot 1816 ½, Catalogue of the rare, curious and valuable library collected by the late Hon. Thos. H. Wynne, of Richmond, VA. … To be sold at auction, in the city of Richmond, Va., commencing on the 14th of July, 1875 (Richmond: J. Thompson Brown, 1875).

For more on the intriguing murder of George Wythe, and the subsequent murder trial of George Wythe Sweeney, see Bruce Chadwick, I Am Murdered: George Wythe, Thomas Jefferson, and the Killing That Shocked a New Nation (Hoboken, N.J., 2009); Julian P. Boyd, “The Murder of George Wythe,”William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 12 (1955): 514-42; and Edwin W. Hemphill, “Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 12 (1955): 543-74.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.2 (January, 2010).

Endrina Tay is Associate Foundation Librarian for Technical Services at Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia, owned and operated by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. She heads the Thomas Jefferson’s Libraries Project based at Monticello.

Jeremy Dibbell is an Assistant Reference Librarian at the Massachusetts Historical Society, and coordinator of the Libraries of Early America Project at LibraryThing.com. He is the author of ““A Library of the Most Celebrated & Approved Authors’: The First Purchase Collection of Union College” (Libraries & the Cultural Record 43:4). Dibbell edits the MHS blog, The Beehive, and also blogs about books, libraries and archives at PhiloBiblos.