Ritualization and Early American Music: Introduction to Common-place 13:2

The articles in this issue of Common-place examine many different dimensions of music in early America. To the historian of religious culture, however, there is also an important element of continuity that links these disparate studies together. It is the process of ritualization that operates through this music across time and space in both religious and non-religious contexts.

Historians tend to think of ritual as a fixed pattern of symbolic behavior, such as the Roman Catholic mass or the five required daily prayers in Islam, that gains its meaning through a set text and invariant performance. A more dynamic and adaptive concept of ritual has emerged in recent years, however, especially through the work of anthropologist Victor Turner and historian of religion Catherine Bell. Their basic idea is that in contrast to ritual’s stabilizing functions, the process of ritualization can also catalyze and symbolize conflict and changing cultural circumstances.

Music, with or without words, has an extraordinary capacity as an agent of ritualization to make symbolic sense of a changing world. All the essays in this issue treat music that registers quintessentially American processes of cultural change—encounter, innovation, contestation, reconfiguration, transfusion. Accordingly, it seems valuable to read them also with an eye to how ritualization contributed to their creation of cultural meaning.

McDougall and DeLucia begin with accounts of English trumpets and drums counterpoised to Kikotan and Algonquian dance and song in primal encounters of peace and violence in the seventeenth century. In these cases, musics that had formerly provided ritual stability suddenly became rivals for symbolic supremacy in their New World encounter, invoking their respective peoples, warriors, and gods first in tentative coexistence and then in fatal conflict.

Gray and Goodman explore how individual Old World songs were textually reconfigured, musically re-presented, and culturally repositioned in the primal political combat between Federalists and Democratic Republicans during the 1790s. In these cases, an iconic English ballad and French Revolutionary anthems of great ritual power in their original national contexts were transformed and redeployed as agencies of public ritualization in a revolutionary society still experimenting with a new mode of political order.

Newcomer, Goodman, and Pappas take this collection into music and ritualization in the world of American Protestant sectarianism and civil religion. Their studies concentrate on music that helped to ritualize Methodism, Shakerism, and Southern nationalism when they were new movements. In these cases, manuscript and printed music served to create new systems of symbolic meaning which, when transmitted through and performed by sectarian constituencies, established the cultural stability critical to their survival.

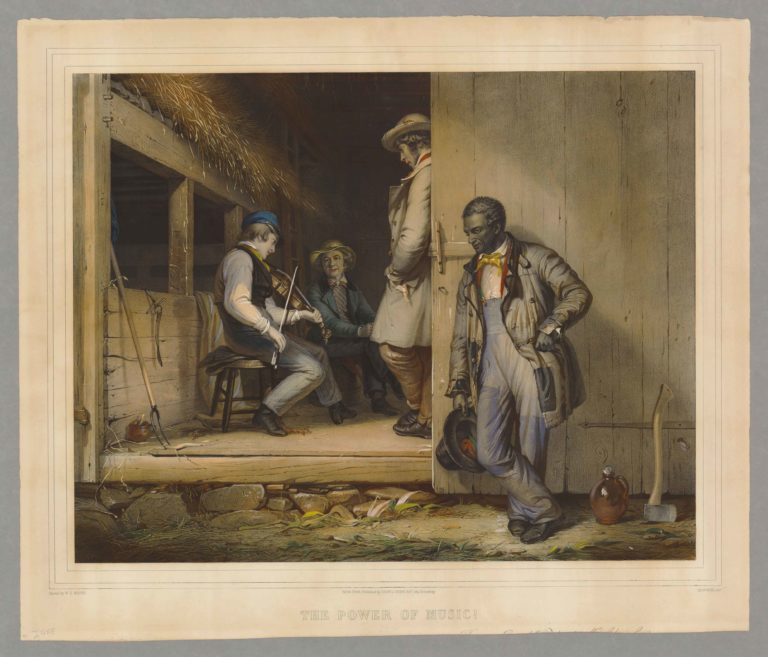

Finally, Masten’s account of the transfusion of African and Irish music and dance suggests powerful processes of ritualization at work both in the creation of the new hybrid genre of “Negro jigs” and in its elaborately codified performance practice.

These brief reflections suggest just the most apparent dimensions of ritualization through music disclosed by these studies. Further reflection on them will reveal important additional aspects of how music serves to ritualize the American experiment’s unceasing processes of change.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).