Salem Repossessed

The typo in the Playbill did not bode well. According to the program, the action of The Crucible begins “in the spring of the year 1792.” Clearly, uncovering the real history of the 1692 Salem witch trials was not a high priority. Like all productions of the play since its premier in 1953, director Richard Eyre’s Crucible, just opened on Broadway, tells us much more about its own time than about colonial America. That strange mixture of timelessness and timeliness is the play’s greatest strength, and, paradoxically, its greatest weakness. It’s always relevant, but always just a little bit trite.

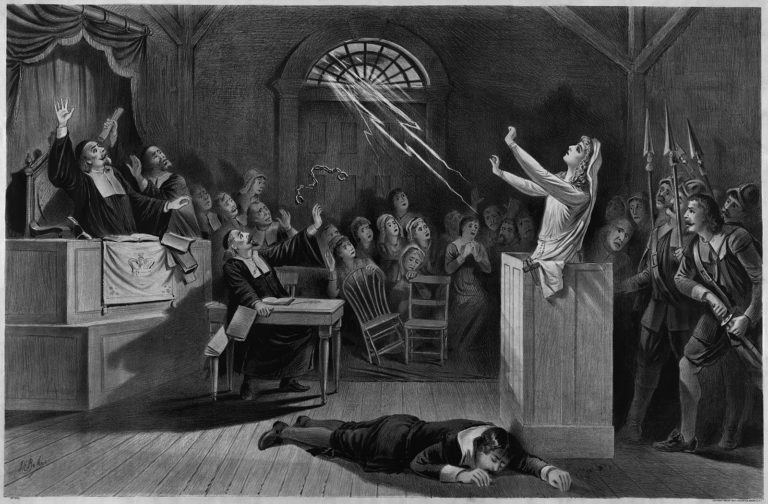

Most Americans learn what they know about the Salem witch trials from high school readings of Arthur Miller’s most famous play. All things considered, this is really too bad. Miller’s Salem–an indictment of McCarthy’s red baiting–is a far cry from the world Cotton Mather knew. A large part of the audience during the preview performance on February 28 was teenagers, including a whole row of students clearly there on school assignment. For these students, as for many college undergraduates, Salem will be forever the story of a young, virile John Proctor (the real man was in his sixties), a seductive adolescent Abigail Williams (who was only eleven at the time of the trials), and a scheme by unscrupulous townspeople to steal land from their neighbors. Most importantly, The Crucible is what most of these readers and theater-goers will associate with the phrase “witch hunt,” whether describing historical events or the rounding up of al Qaeda suspects.

Eyre’s production, at the Virginia Theatre, first announces its interpretation of witch-hunting through its sets. Tim Hetley’s set design and Paul Gallo’s lighting present us with stark, bare rooms, illuminated from above with streaks and bars of light. The effect manages to suggest at once a church and a prison, a combination that reflects prevailing popular opinion about the Salem trials: that they were a product of an oppressive religion mixed with unyielding government authority. This is in fact the interpretation that Miller himself put forward in his notes on the script: that the trials were about the power of “theocracy” in New England.

Eyre presses this point too far. When Tituba (Patrice Johnson), the Reverend Samuel Parris’s West Indian slave, is accused of witchcraft in the first act, she quickly confesses, with Parris egging her on. Eyre plays this scene like a televangelist revival meeting, with Tituba waving her hands above her head and chanting her lines in a near-parody of Southern Baptist singsong. One almost expects Parris (Christopher Evan Welch) to turn to the audience and ask for donations or for Tammy Faye to enter, stage right. Eyre’s attempt to modernize the magico-religious worldview of seventeenth-century Calvinists falls flat, and inspired little more than laughter from the audience.

Indeed, the full hall at the Virginia Theatre snickered every time God, the Devil, or magic was mentioned. For a New York theater-going audience the notion that such ideas could carry intellectual and emotional weight seemed ludicrous. They even tittered during a scene in which the possessed girls turn on one of their own–one of the most terrifying moments in the play.

And yet the audience was drawn into the play’s world. The other half of theocracy’s power, the power of unrestrained legal authority, is something Americans–especially those who’ve sat through a few too many Oliver Stone movies–can easily comprehend. Eyre makes the law’s abusive power the emotional center of the production. He presents John Proctor (Liam Neeson) not as a man brought down by sexual indiscretion with a scheming woman, Abigail Williams, but as Everyman caught in a Kafkaesque legal system.

One disadvantage of this approach is that Abigail (Angela Bettis) becomes a mere device to set the action in motion. This may explain why Bettis’s performance seemed uninspired. Despite her vixenish beauty, there is little sexual spark between her and Neeson. Bettis’s speeches about the hypocrisy of Salem’s “Christian women and covenanted men” are delivered dutifully, without the seething resentment that the script suggests. Even Abigail’s best scene–where she turns on her former ally Mary Warren in order to discredit Warren’s recantation–plays here like the revenge of a junior high alpha girl. Similarly, Laura Linney’s Elizabeth Proctor fades into the background. Her character seems truly to be little more than, in Abigail’s words “a cold sniveling woman.”

Since putting the law at the center of the play pushes the female characters to the margins, it is doubly important that the male leads capture the audience’s imagination. And they do. Neeson portrays John Proctor as a man whose independence and simple moral code tragically bring about his downfall, a portrayal well suited to Neeson’s physicality: his broad shouldered physique and bluntly handsome face fit Proctor’s earthy personality. The director takes advantage of this asset by having Proctor strip to the waist and vigorously splash himself with water on his return from the fields. The scene serves to distance Proctor from the (unearned) stereotype of the “Puritan”–a sexless, repressed human being who is a hypocrite at heart. As Proctor splutters and stamps, suddenly Abigail’s description of him as a “stallion” rings true, and not just the sexual connotation. This is a man who will take action without giving much thought to possible consequences.

Proctor’s main adversary is the steely Deputy Governor Danforth (Brian Murray). Danforth’s faith sustains him and gives him moral certainty even as innocents go to the gallows. In this spirit, he delivers what may be the most chilling speech in the play, expounding upon the necessity for relying on spectral evidence in cases of witchcraft, with reasoning that is in fact very close to seventeenth-century thinking on the matter: “Witchcraft is ipso facto, on its face, an invisible crime, is it not? Therefore who may possibly be witness to it?” Murray delivers these lines with a cold conviction and unctuous reasonableness that brooks no disagreement.

Proctor finds himself caught in this nightmare logic. When he tries to disprove the unprovable, he himself is accused. In the end, it is Proctor’s virtue that is his tragic flaw, ably embodied by Neeson. Clenching and unclenching his fists, Neeson’s decision to die rather than give a false confession seems wrung from him against his will–but once he makes it, he walks offstage to the gallows with the same bullheaded determination that characterizes his entire performance. And here, at last, the audience was won. The same crowd that laughed at God and the Devil sat rapt as Proctor made his moral choice (and greeted Neeson with a standing ovation at his curtain call).

Historians as well as artists, over the years, have offered more than a few interpretations of what really happened in Salem in 1692. But the use and abuse of power lies at the heart of all of them. What kind of power is abused is a sign of the times. Most recently, a 1996 Hollywood film starring Daniel Day Lewis and Winona Ryder presented the witch trials as a parable about sexual harassment (of Proctor by Williams, in a sort of seventeenth-century version of Fatal Attraction.) The current Broadway production focuses squarely on how fear of hidden evils can lead to abuses of the law, blindly supported by an unthinking public. History may have been the last thing on the audience’s mind in New York in this year of tragedy, but, in the end, they could not help but be profoundly moved by a Crucible that plays like a cautionary tale about the loss of civil liberties.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.3 (April, 2002).

Rebecca Tannenbaum is visiting assistant professor of history at Yale University and the author of the forthcoming Healer’s Calling.