Searching for Love and Security across the Color Line

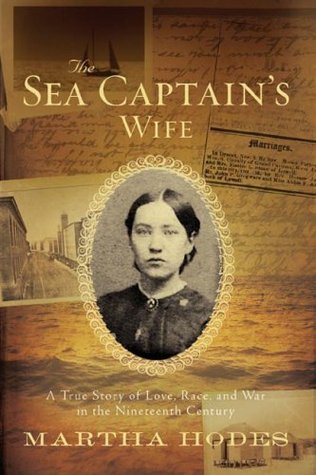

Martha Hodes has produced a masterfully written narrative biography complete with intrigue, suspense, and fastidious detail regarding nineteenth-century life in the United States and the Cayman Islands. The Sea Captain’s Wife is a book about many things, but it is primarily the story of Eunice Richardson Stone Connolly. In many ways, Eunice was an ordinary woman in nineteenth-century America. Born in 1831 on a farm in Northfield, Massachusetts, she worked hard for most of her life in the mills of New England, as a washerwoman, and as a domestic. Most of Eunice’s life was spent attempting to change her station in life, that is, to climb out of poverty through hard work performed by her own industrious hands or through other avenues such as marriage. Eunice wanted desperately to find stability, happiness, and comfort for herself and her family; however, many of these things eluded her. Unable to attain security and a life free from poverty, Eunice made a decision that was unconventional for the late nineteenth century: she crossed the color line and married Captain William Smiley Connolly, a black sea captain who would move his new bride and family to Grand Cayman Island.

Martha Hodes came across the letters of the Richardson family, housed at the Duke University library, and has combined detailed archival work and oral history with stubborn perseverance to create an imaginative narrative. The Sea Captain’s Wife is a work that will capture the attention of anyone working in women’s history, African American history, urban history, and biography. It offers a beautifully written description of life, love, and race in nineteenth-century America.

“Change felt relentless in an industrializing city,” writes Hodes (56). Eunice’s life was similar to many other northern women who moved from the farm to the factory. She lived in Manchester, New Hampshire, the largest city in the state, and worked at the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company. She would eventually marry William Stone, a carpenter and a supposed answer to her prayers for a secure and happy life. But like many other nineteenth-century artisans whose skills fell from fashion as factories dotted the northern landscape, William found himself chronically unemployed. The Panic of 1857 moved the family closer to destitution as they moved frequently from rented dwellings to the homes of family members. By 1859, the desperation felt by Eunice and her husband was immense and drove William to leave a familiar New England and to join Eunice’s sister and brother-in-law in Mobile, Alabama. William hoped desperately to regain the security and respectability connected to skilled labor and left his wife and child to toil in New England while he tried his luck in the South.

Eunice became one of the many women forced into low-paying factory work when her husband set out for Alabama. She was forced to leave her young son Clarence with a widow who lived in West Manchester and felt very much alone. Hodes suggests that Eunice’s longing for a traditional patriarchal home in which she was cared for remained constant, but her work and perhaps the geographical distance from William began to erode her husband’s authority, and Eunice began the practice of making her own decisions. In a short time, Eunice decided to move to Mobile, to end her work in the mills, and to be reunited with her child and husband. Eunice made the long and dangerous journey and was hopeful for a better life in Mobile, but her hopes fell short once again when William fell ill and was unable to work.

Eunice became quickly disenchanted with the South, and Hodes suggests that she became uncomfortable with “the peculiar institution.” Within the text of her many letters sent to family members back North, Eunice “offered nary an opinion, not even a description” of slavery and its brutality (89). Although William decided to enlist with the Confederate Army, Eunice remained committed to the North and the Union cause. “I am with the North,” she wrote to her family, “though I have to keep it to my self” (101). Hodes suggests that Eunice was forced into autonomy. Once again abandoned by her husband and afflicted with uncertainty and poverty, Eunice began to direct her own life; she returned to the North. Seven months pregnant, Eunice made the long winter journey with her young son. Eunice’s was a bold and untraditional move, but as Hodes writes, “truth be told, William had never proved much help anyway. If Eunice was going to be poor, she would rather be poor at home, close to her mother and sisters, even without a husband” (117).

Life was difficult for Eunice. After the birth of her daughter, Eunice was barely able to survive on wages from domestic work. To make matters worse, the Civil War tore apart her family. In September of 1864 Eunice’s brother Luther Jr., who fought for the Union army, was killed in battle, and in the final months of the war she was to learn that her husband William died in a Confederate hospital in Atlanta. Eunice, deeply depressed, hung onto life and made another controversial decision: she met and married Smiley Connolly, a black entrepreneur who was a member of the elite on Grand Cayman Island. According to Hodes, this decision to marry outside of her race and to move to Grand Cayman was very unorthodox, yet it saved Eunice from the work, poverty, and depression of her life as a single mother. Eunice wrote that she did not think about race when she thought about her husband. “I do not look at that when I look at him, I look for a loving glance of his eye which I always meet” (197).

Life for the Connollys on Grand Cayman Island appeared to be happy and at last secure. Eunice loved her husband and her life of moderate wealth, yet she missed her family and yearned for their correspondence. Tragically, in 1877, the Connollys were lost at sea when a hurricane turned a turtle-fishing adventure into an early demise.

Although Martha Hodes is forced to rely on speculation throughout much of her work, she has done so with believable and probable accuracy.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.1 (October, 2007).

Erica Armstrong Dunbar is an associate professor of history at the University of Delaware.