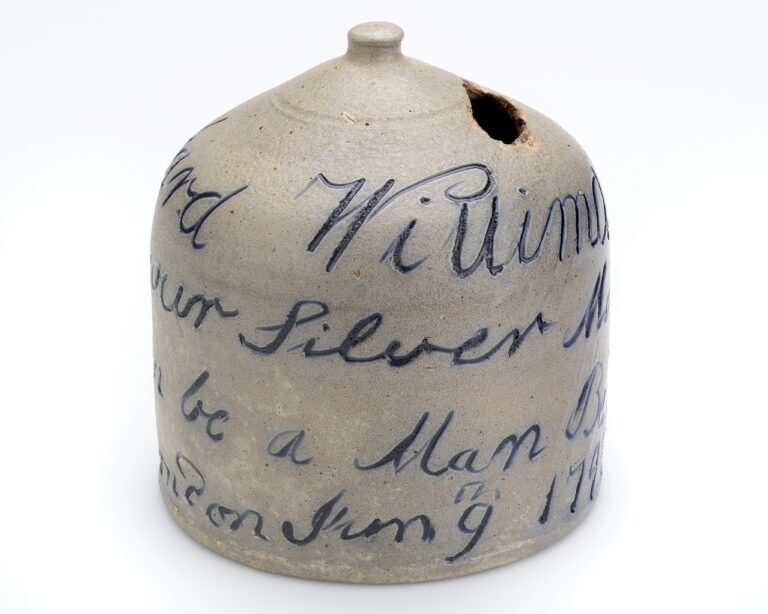

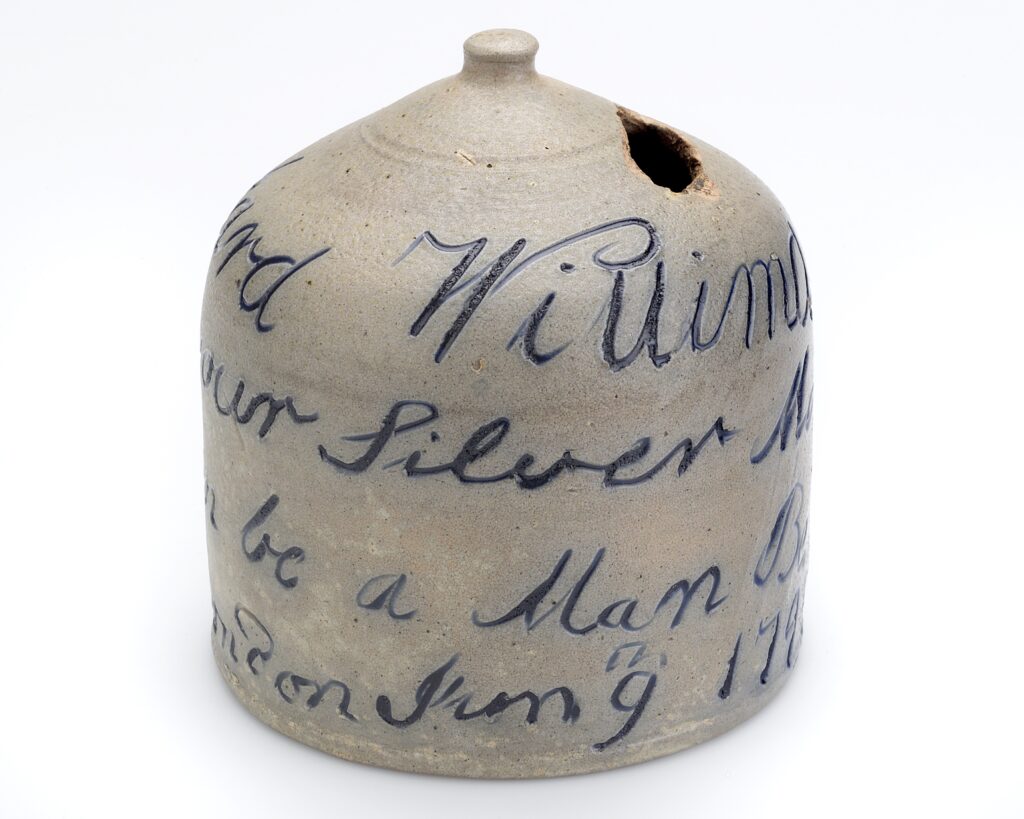

Those who benefited from the circulation of salt came to include Richard Williams, who became a successful Essex shipwright in his own right and whose prominence there got him elected to the Connecticut state legislature in 1851. The only cause for doubt in attributing the salt-glazed bank to this Richard Williams is Samuel Williams’ decision to give his son a middle name that honored one of Essex’s three original families, the Pratts. In the archival records, Samuel’s son often appears as Richard P. Williams. While it is troubling that there is no “P” on the savings bank, it could be that it was Richard who decided to use his middle initial in adulthood. If the survival of his savings bank in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is any indication, the Richard Williams who owned it seems to have believed that his rise was a result, not of his connections, but his individual efforts. Rather than smashing the bank once it was full of coins, as was and remains customary for clay and glass piggybanks, either he or someone who also appreciated the tenets of individualism used a chisel to carefully enlarge the coin slot and thereby extract the saved silver coins while preserving all the words incised in it.

No one, it seems, was ever bothered by the transposition of two letters in the name Williams. Perhaps the bank’s purchaser did not notice the error upon receipt of the fired bank. Readers recognize words by global letter patterns, not by the identity and position of each letter, and they are thus quick to silently correct transposed adjacent letters without even realizing it. Given that the bank’s purchaser did not reject the bank after it was completed, he or she may not have noticed the error until arriving back in Essex. Today, however, the transposition seems fated, a small reminder of something much larger baked into American salt-glazed stoneware produced prior to the demise of plantation slavery. In her autobiography, Mary Prince testified to what she endured to produce its attractive glaze:

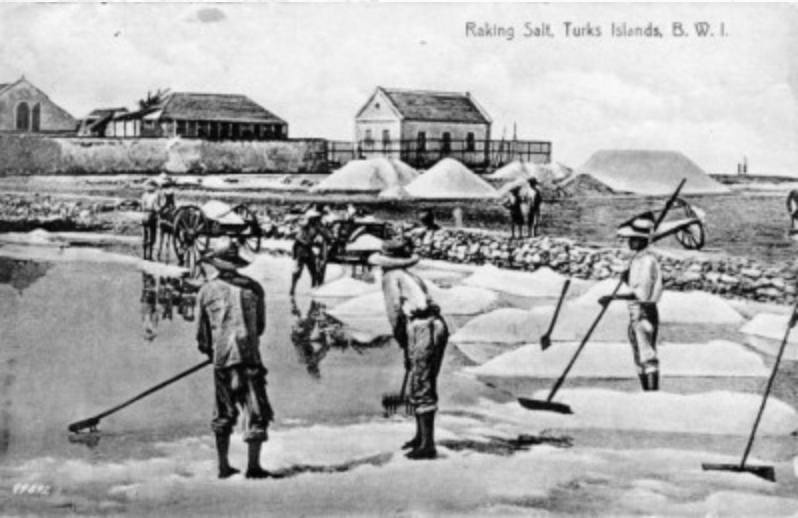

Sometimes we had to work all night, measuring salt to load a vessel; or turning a machine to draw water out of the sea for the salt-making. Then we had no sleep—no rest—but were forced to work as fast as we could, and go on again all next day the same as usual. Work—work—work—Oh that Turk’s Island was a horrible place!

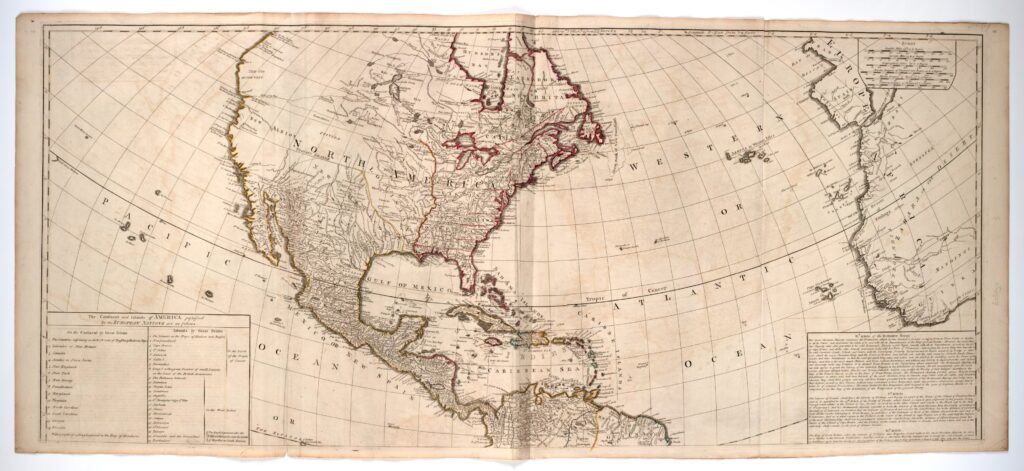

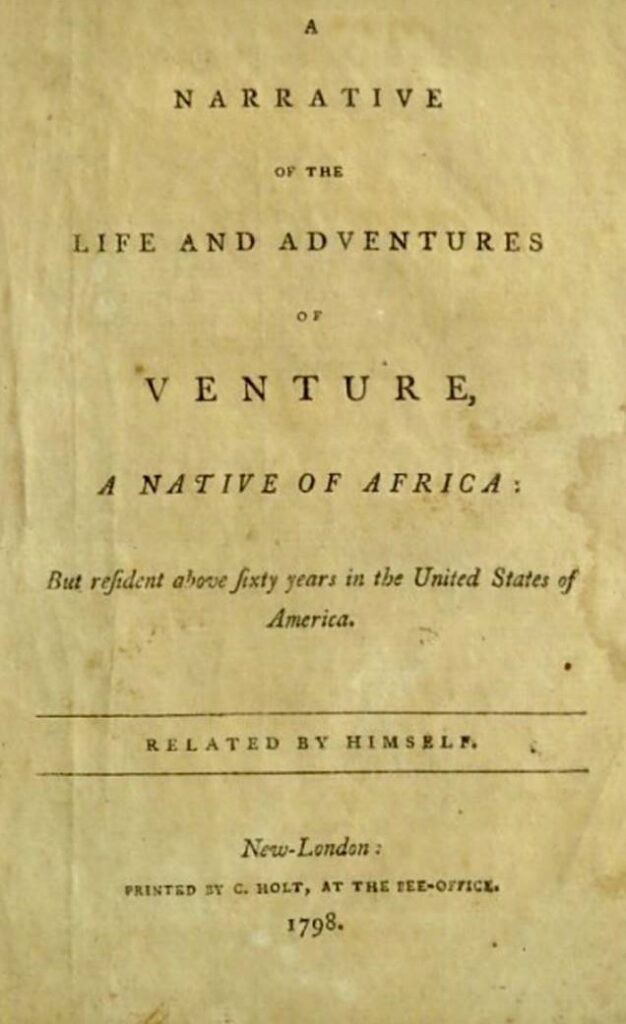

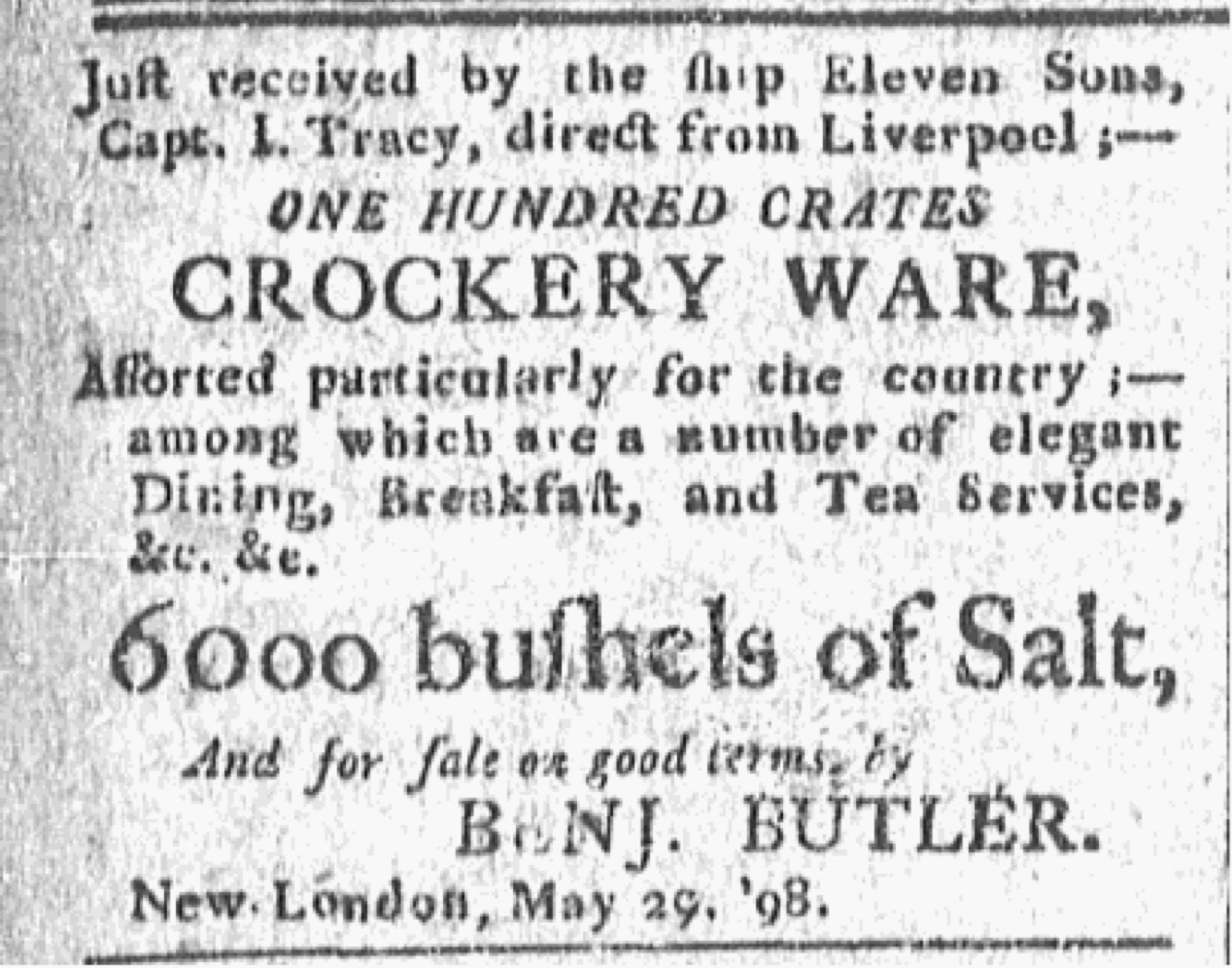

This article has traced the hidden double role of slavery in the salt-glazed stoneware savings bank, first in a family’s firm conviction that individual virtues were the reason for their rise even despite its patriarchs’ involvement in the West Indies trade, and second in the labor of the enslaved in raking the salt that gives the bank and its message its deceptive luster. Of course, just as another Richard Williams may have owned this savings bank, there could be early American stoneware that was glazed with salt from England or Europe. However, to insist on as much is to erase Venture Smith and Mary Prince’s experiences. Their voices make clear that the circulation of salt and salted fish between New England and West Indies slave plantations shaped everyone’s lives as indelibly as cobalt oxide seared in fire.

Further Reading

On New England pottery: Lura Woodside Watkin, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950).

On Connecticut River Shipbuilding and the Williams Family: Essex Historical Society and Essex Land Trust, Falls River Cove, vol. 1 of Follow the Falls, https://engage.overabove.com/follow-the-falls-volume-1-falls-river-cove/0627097001526997901; Shirley H. Malcarne and Donald L. Malcarne, “The Williams Building (Boat) Yard, 1790-1840: A Study of an Early Essex Ct. Enterprise and the Ships it Sent to the Sea” (1991); Wick Griswold and Ruth Major, Connecticut River Shipbuilding (Charleston: The History Press, 2020).

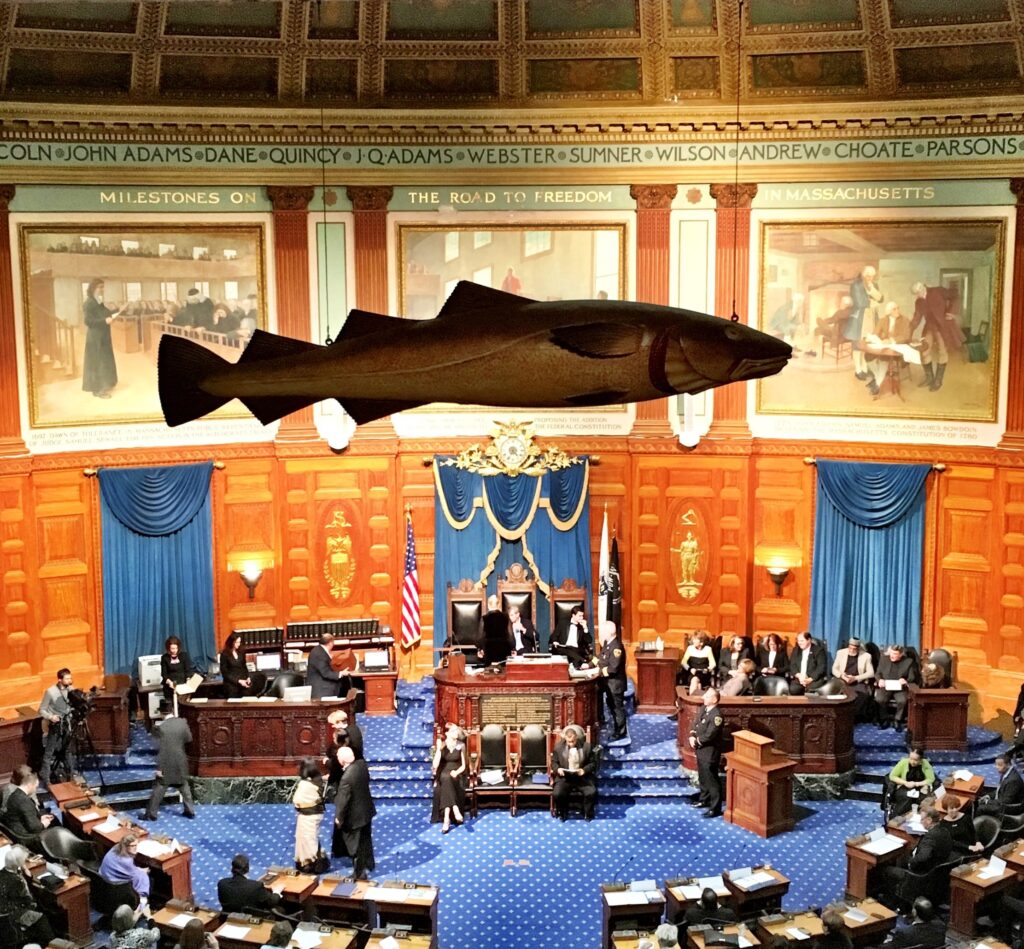

On salt: Konrad A. Antczak, Islands of Salt: Historical Archaeology of Seafarers and Things in the Venezuelan Caribbean 1624-1880 (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2019); Cynthia M. Kennedy, “The Other White Gold: Salt, Slaves, and Turks and Caicos Islands and British Colonialism,” The Historian 69 (no. 2, 2007): 215-30; Mark Kurlansky, Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World (New York: Walker and Co., 1997); Mark Kurlansky, Salt: A World History (New York: Walker and Co., 2003).

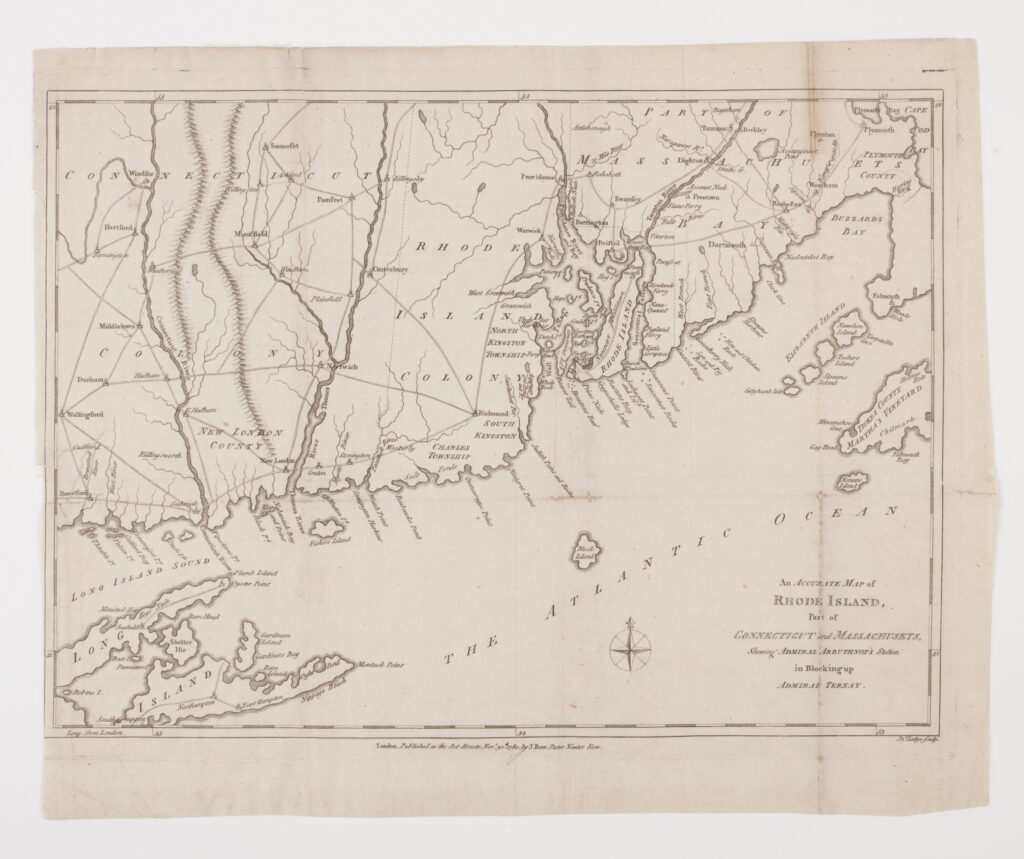

On slavery in New London, Connecticut: Taylor Desloge, “New London: A Fault Line in the Story of Freedom and Slavery in the Atlantic World,” Segregation and Community on New London’s Hempstead Street, https://segregationnewlondon.digital.conncoll.edu/why-new-london-a-fault-line-in-the-battle-over-slavery-and-freedom-in-the-atlantic-world/.

On Mary Prince and accounting, see Katrina Dzyak, “Atlantic World Accounting and The History of Mary Prince (1831),” Commonplace: the journal of early American life, accessed June 11, 2024, https://commonplace.online/article/atlantic-world-accounting/.

This article originally appeared in August 2024.

Elise Lemire is Professor of Literature at Purchase College, SUNY, and the author of Battle Green Vietnam: The 1971 March on Concord, Lexington, and Boston and other titles. Her book Black Walden: Slavery and Its Aftermath in Concord, Massachusetts is available on Audible.