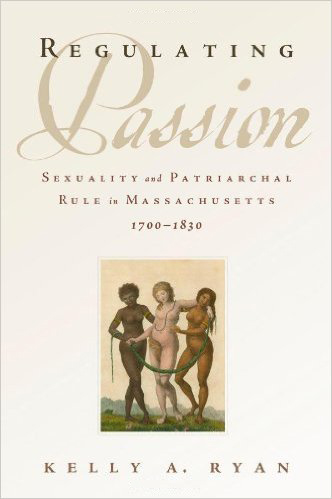

Sex and Social Order in Massachusetts

Kelly A. Ryan’s work, Regulating Passion: Sexuality and Patriarchal Rule in Massachusetts, 1700-1830, explores the intersections of patriarchal power and sexual regulation in Massachusetts from the late colonial era through the early national period. Drawing on a wide array of sources, including legal records, print culture, letters and diaries, and church records, she argues that the regulation of sexual behavior was one of the cornerstones of white men’s patriarchal authority. Ryan defines patriarchal power as the “authority of men in households, government, economics, sexuality, religion, and culture,” as well as “the direct power of male heads of household over their dependents’ sexual, economic, and religious choices” (2). She uses both anecdotal and statistical evidence to show that this authority was manifested in many ways, from the prosecution of white women for fornication in the court system to the control of enslaved people’s marital choices.

Although the close reliance of patriarchal authority on sexual regulation remained constant throughout the period in question, Ryan argues that the American Revolution and the emergence of the new nation facilitated challenges to patriarchal authority and contributed to shifting methods of sexual regulation. In the late colonial period, she shows, sexual regulation largely occurred through official channels of authority—the authority of fathers over children, of masters over servants and slaves, and of courts and public officials over the behavior of all residents. After the American Revolution, however, sexual behavior was less likely to be policed via official channels of power; instead, a new culture of virtue and reputation sought to shape individual behavior by emphasizing the importance of sexual virtue and self-regulation.

Ryan’s book is divided into two sections. The first part explores sexual control in the late colonial period and focuses on efforts to regulate the behaviors of white, Native American, and African American women and men. At a time when rates of premarital sex were increasing and when print culture depicted the dangers of women’s erotic power, Ryan shows that government authorities particularly focused on containing the dangers of white women’s sexuality within lawful marriage. Fornication prosecutions in particular sought to control women’s sexual behavior, and the courts made white women uniquely culpable for sexual transgressions. White men, on the other hand, enjoyed far greater sexual license. They were rarely prosecuted for fornication, and paternity suits were one of the few avenues through which white men’s sexual misdemeanors were brought before the courts and the public. Yet in spite of this sexual liberty, young white men and poor white men found that their behaviors and choices were constrained by the realities of dependence—dependence on fathers, masters, and the overseers of the poor.

At a time when rates of premarital sex were increasing and when print culture depicted the dangers of women’s erotic power, Ryan shows that government authorities particularly focused on containing the dangers of white women’s sexuality within lawful marriage.

In many ways non-white women and men faced similar constraints on their sexual behavior. White men believed that their patriarchal authority and responsibilities extended to Native Americans and African Americans, whom they viewed as racially and culturally inferior and therefore dependent. Ryan argues that over the course of the eighteenth century, white patriarchal authority over Native Americans increased. Systems of indentured servitude and guardianship, as well as missionary efforts, provided multiple avenues for imposing white sexual norms on Native communities and families. For African Americans the system of slavery provided white men even greater scope for sexual regulation. Of particular concern for white authorities was the prevention of interracial sex and marriage. Ryan reveals fascinating inconsistencies in the ways interracial sex was policed. White women were more severely punished when prosecuted for fornication with African American men than with Native American or white men. Conversely, like white men, African American and Native American men were rarely prosecuted for fornication with white women. Unlike white women, African American and Native American women were rarely prosecuted for fornication, whether or not they crossed a racial boundary. This gave white patriarchs considerable license to cross racial boundaries without having their behavior exposed in public. As Ryan explains, “By not prosecuting African American or Indian women for fornication, masters of servants and slaves were implicitly protected from any financial or criminal charges being brought against them for engaging in interracial sex” (78). Ultimately, Ryan shows that in virtually any situation, white women bore the burden of maintaining racial boundaries.

The second part of Ryan’s work examines shifts in sexual regulation that occurred during and after the American Revolution. Ryan argues that sexual regulation shifted away from legal and institutional avenues of power and toward cultural strategies by which sexual values could be explained and promoted. This shift was prompted by developments such as a new emphasis on equality that elevated the status of young men and poor men to that of virtuous citizens capable of governing themselves. Even churches, which formerly had emphasized public regulation of members’ behavior, moved away from rituals of public confession and repentance toward new values of self-regulation and private intervention. Moreover, legal prosecutions of sexual misbehavior such as fornication and adultery declined in this period.

In addition, one of the most significant changes in this post-revolutionary period was the emancipation of slaves in the wake of the revised Massachusetts state constitution in 1780. With legal authority over African Americans reduced, Ryan argues that “many whites drew on cultural strategies to sustain the racial hierarchy rather than institutional and legal controls” (105). Print culture, for instance, drew increasingly stark racial divisions by insisting that African Americans (and Native Americans newly eligible for citizenship) did not experience genuine feeling and attachment—they were merely lustful and uncontrolled. More practically, new social patterns of segregation emerged in towns and cities, thus drawing spatial boundaries in addition to cultural lines between the races.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, moreover, white women writers began to carve out a new role for themselves in the republic, emphasizing their moral and intellectual capacities. In particular, Ryan shows that white women intervened for the first time via print culture in the system of sexual regulation that sought to put the greatest burden on them. In essays, stories, and novels, they openly criticized men’s unruly sexual behavior and called for an end to the sexual double standard that held women more responsible than men for good sexual behavior. Seduction narratives in particular proved popular with readers and offered women a narrative structure for demonstrating that innocent women were in danger of being led astray by unscrupulous men who needed to be held responsible for their actions.

White women’s writings constitute one of Ryan’s most convincing examples of resistance to patriarchal authority; these writers effectively increased the scrutiny of white men’s sexual behavior and pushed readers to regard “fallen” women with greater sympathy. As Ryan argues, “middle and upper rank white women asserted a new place for themselves as the arbiters of sexual morality in their criticism of men’s sexual behavior and defense of women” (150). These women certainly did not unravel patriarchal authority, but they did shift some of the burden of sexual regulation away from themselves and onto white men.

Ryan’s work has many strengths, most notably her ability to analyze differences of race, class, gender, and age without losing sight of her broad interpretation of shifts in sexual regulation from the late colonial to the early national period. Moreover, her ability to address both changes in sexual regulation and continuities in patriarchal power is important and necessary in conveying the complexity and sources of white men’s authority. She emphasizes the constancy of white men’s patriarchal power during this period while still revealing the challenges posed by individuals, groups, and new ideological trends. By highlighting these challenges, Ryan is able to expose the ways in which patriarchal authority shifted and transformed to meet these pressures. Ultimately, she reveals the resilience at the heart of enduring systems of power.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.4 (Summer, 2015).

Nora Doyle is an assistant professor of history at Salem College. Her research focuses on women’s and gender history and the history of sexuality in early America.