Shivering Timbers: Sexing up the pirates in early modern print culture

“Now, men, I run a man’s ship. I will run it in a manful and masculine way! I will tolerate no men under my command who act in such a way so as to discredit their manhood and manliness!” So it was that John Belushi, as “Captain Ned,” introduced his ship in a Saturday Night Live sketch from 1979. The sketch had its Dickensian protagonist, Miles Cowperthwaite (a wide-eyed Michael Palin), encounter a bawdy world of sex, homosexuality, and masochism aboard the Raging Queen, a ship so wholly linked to a gay world at sea that the writers did not bother to let us know whether it was British Navy or merchant marine. Moreover, in the cheap homophobic tradition of television writing (which was, sadly, not unique to the 1970s), they have Cowperthwaite discover that the crew dedicates so much of its time to suntanning, enforcing corporal punishments, and searching, wistfully, for pirates that they make little forward progress.

Successful the sketch was not. The over-the-top gay cracks couldn’t make up for a fizzling conclusion. Nevertheless, Miles and Captain Ned earned a fond place in the hearts of many viewers because the skit’s founding gag relies on some of the obviously gendered and highly sexualized elements of the “man’s life at sea” that have become stock conventions in representing seafaring and piracy. Whether we think of Johnny Depp’s gender-bending Jack Sparrow or the courtship antics of The Pirates of Penzance, gender and sexuality play primary roles in popular portrayals of piracy.

Ubiquitous as they are now, these conventions have a long history, one that is rooted as much in the history of the book trade as it is in the history of seafaring. Familiar representations of pirates, in particular, were born during the “golden age of piracy” (from roughly 1670 to 1730) and were reworked and codified in numerous illustrated books published in Europe and circulated throughout the Atlantic. These volumes developed, reiterated, and augmented stereotypes about pirates to attract and titillate middling to elite European and American readers who could afford illustrated books and whose lives adhered to far more staid standards of behavior than the ones exhibited by the fictional pirates. Early modern readers encountered pirates as a series of literary and pictorial conventions that emerged in the late seventeenth century—books like Alexandre Exquemelin’s Bucaniers of America (1678) and Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates (1724), which earned immense popularity by combining mesmerizing narration with vivid, full-page illustrations of pirates. The pirates they depicted radiated a hyper masculinity, at once morally ambiguous and socially transgressive. Were these men admirable and manly rogues or cowardly, vicious villains? Books did not say. But whatever readers decided, their conclusions rested on texts, images, and the interplay between the two.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the pirates who disrupted trade in the Caribbean, West Africa, North America, and all points in between seemed to exemplify the dynamism made possible by maritime movement across the Atlantic Ocean. These men (and, famously, some women) formed international crews so fearsome that they proved to be major impediments to orderly European economic exchange. Just as European nations sought to create reliable and predictable means of drawing goods from the New World to enrich the Old, pirate ships became more numerous and audacious in their attacks, looting twenty-five hundred merchant vessels in the ten years between 1716 and 1726 alone. In fact, it’s surprising we hear so little about their devastating effects on European trade; one eighteenth-century commentator estimated that England lost as much to pirates during the early eighteenth century as it did to Spain and France during the catastrophic War of the Spanish Succession fought between 1701 and 1714. By the 1720s Parliament began to enact harsh new laws against piracy and to conduct well-publicized criminal trials to hang pirates for their misdeeds, seeking with this display of juridical force to discourage what had clearly become a highly lucrative line of work.

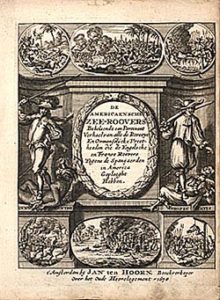

As important as piracy was to European and American political, economic, and maritime history, early modern print media developed modes of describing and representing pirates that sparked readers’ imaginations and that continue to shape pirate conventions today. The urtext is Alexandre Exquemelin’s De Americaensche Zee-Rovers(translated as Bucaniers of America shortly thereafter), an octavo volume with twelve full-page copperplate illustrations, or “cuts,” which emerged from Jan ten Hoorn’s Amsterdam press in 1678. Exquemelin’s own experience as a buccaneer in the Caribbean made his breathless narrative all the more authoritative. His first-hand reports of terrifying pirate leaders and his description of their lair on the tiny island of Tortuga provided European readers with new information about criminals as well as the Caribbean. But Exquemelin also supplied a narrative of action and adventure that went far beyond the more sober descriptions of travel common in the era. Bucaniersoffered an insider’s view of dramatic sieges, torture of Spanish leaders, and freewheeling pirate life.

Sales of the initial edition were so strong that the book shortly thereafter appeared in German (Nuremberg, 1679), Spanish (two editions printed in Cologne, 1681 and 1682), English (at least eight London editions between 1682 and 1704), and French (at least six Paris and Brussels editions between 1686 and 1713), as well as a second Dutch edition in 1700; it would be revived in the 1740s for publication through the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth by presses on both sides of the Atlantic. The book appeared in the libraries of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia and other wealthy American colonists as well as in the Social Library of Salem, Massachusetts, indicating that it had appeal far beyond the confines of England and northern Europe. The fact that the Dutch printer included twelve cuts in the book—four portraits, six action scenes, a map of Panama, and a fully illustrated title page—indicates his faith in the book’s success, for the cost of such work would have been considerable. Given the book’s octavo size, the engravers likely took several weeks or more to cut each plate; once completed, printing the images for a five-hundred-copy edition would have taken three laborers at least twenty-four days; altogether, each print would have cost the printer as much in labor and supplies as his own printing of twenty-four pages of text in letterpress. Clearly, the investment of time and money was rewarded: by any standard for the day, Bucaniers was a bestseller.

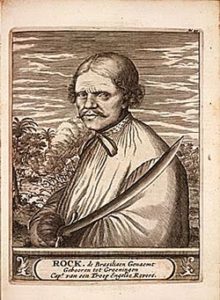

Printers were the first to puff the book as a novel and a thrilling read. A London printer confessed in the preface to his 1684 edition that he had never even heard the term “buccaneer” until this volume, nor had he been aware of the extent of Caribbean piracy. In recommending it, he stressed most of all that the book “informeth us (with huge novelty), of as great and bold attempts, in point of Military conduct and valour, as ever were performed by mankind; without excepting, here, either Alexander the Great, or Julius Caesar, or the rest of the Nine Worthy’s of Fame.” He went so far as to describe Exquemelin’s pirates as English national heroes because they so frequently outwitted the Spanish, who were cast as heavies in the London edition. (This was a stretch, for these men were so thoroughly non-national figures that one of them, “Rock. Brasiliano,” who apparently hailed from the Low Countries, obtained his name by means of a residence in Brazil.)

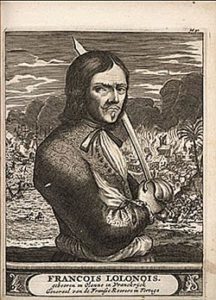

Even without the puffery, the book was an easy sell. Exquemelin used a breezy narrative style and light humor to describe his subjects. “After a fight of almost three hours, wherein they behaved themselves with desperate Courage, … they became Masters [of the city of Maracaibo, in Venezuela] having made use of no other Arms than their Swords and Pistols,” he explained of François Lolonois’s dramatic defeat of the Spanish. Invariably outmanned and outgunned, his pirates managed to take Spanish ships and entire towns; they escaped from custody no matter how tight the security. Sustained by an insatiable appetite for riches, Exquemelin’s pirates were alarmingly careless with treasure once they had gained it: they invariably gambled away vast sums or pissed it away on trifles. This occasioned no bitterness on the part of the pirates, who seemed to view such drastic reversals as incidental to their way of life. Lolonois and his men provide a case in point. After capturing Maracaibo, they stole “twenty thousand Peices of Eight, several Mules laden with Houshold-goods and Merchandize, and twenty Prisoners, between men, women, and children. Some of these Prisoners were put to the Rack, onely to make them confess where they had hidden the rest of their Goods.” Within weeks, the pirates threatened again to burn the town unless they received an additional ten thousand pieces of eight; this threat was followed up by yet another demand for thirty thousand lest the Spaniards’ homes “be entirely sack’d anew and burnt.” Yet upon their triumphal return to their home on the island of Tortuga, “they made shift to lose and spend the Riches they had gotten, in much less time than they were purchased by robbing.” How was the wealth redistributed? “The Taverns and Stews, according to the custom of Pirats, got the greatest part,” Exquemelin remarks wryly.

Although Exquemelin never paused to describe his antiheroes, he liked to include extensive depictions of the grisly tortures they inflicted on unlucky victims. Physical cruelty of all kinds threads through the pages of Bucaniers of America, marking a departure from narrative conventions of the day. Exquemelin explained that when the sadistic Henry Morgan and his men refrained from putting men to the rack, they liked “to stretch their limbs with Cords, and at the same time beat them with Sticks and other Instruments. Others had burning Matches placed betwixt their fingers, which were thus burnt alive. Others had slender Cords or Matches twisted about their heads, till their eyes bursted out of the skull.” In a rare moralizing moment he added, “Thus all sort of inhumane Cruelties were executed upon those innocent people.” He described sexual viciousness like the “insolent actions of Rape and Adultery” of “very honest women” to evoke the corporal horrors of Caribbean piracy. Indeed, Exquemelin’s descriptions of somatic cruelty veered close to a certain vein of late seventeenth-century pornographic writing that emphasized the erotic nature of flogging and the brutal ravishing of women, among other perversions.

Impulsive and volatile, brave and rapacious, the pirates who came to life on the pages of Bucaniers of America served up an alternative model of manliness. Readers didn’t have to venture far into Exquemelin’s chapters to figure this out. Editors made sure to underscore the pirates’ manliness and bravery when they composed prefaces advertising the book’s pleasures. They invariably highlighted the buccaneers’ “unparallel’d, if not unimitable, adventures and Heroick exploits,” as the 1684 edition put it. By 1704, the London printer heralded the book’s “wondrous Actions, and daring Adventures,” claiming that all but “the most stupid minds” could not help but admire them. Here the editor finessed the question of the pirates’ sexual license and propensity for rape, conceding half-heartedly that these men lacked the “Justness and Regularity” that marked a Christian man and even the “tolerable morals” of more run-of-the-mill citizens. Yet even taking their moral failings into account, the editor assured readers that “a bolder Race of Men both as to personal Valour and Conduct, certainly never yet appear’d” on land or sea. London and Dublin printers reiterated these themes (and even lifted some of the same sentences) when the book reappeared in print in 1741, reminding readers again that they ought to admire and even emulate the buccaneers for their courage and daring, particularly because so many of them were English. This seemingly contradictory group of repeated themes in the prefaces of various editions—the pirates’ admirable courage and alleged Englishness, on the one hand, and their rejection of conventional morality and hierarchy on the other—combined to depict a dangerous, exciting mode of masculine action and behavior. In none of these ways did pirates conform to prescribed models of European manliness of the time (and particularly of the middling and wealthy men who likely purchased the book)—ideals of masculinity that tended to stress fiscal responsibility, sexual control, and judicious understanding of one’s social place. Buccaneers did more than merely ignore such advice: they repudiated it.

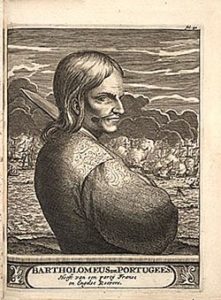

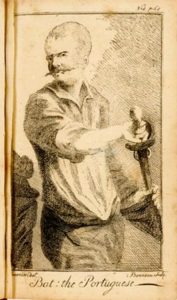

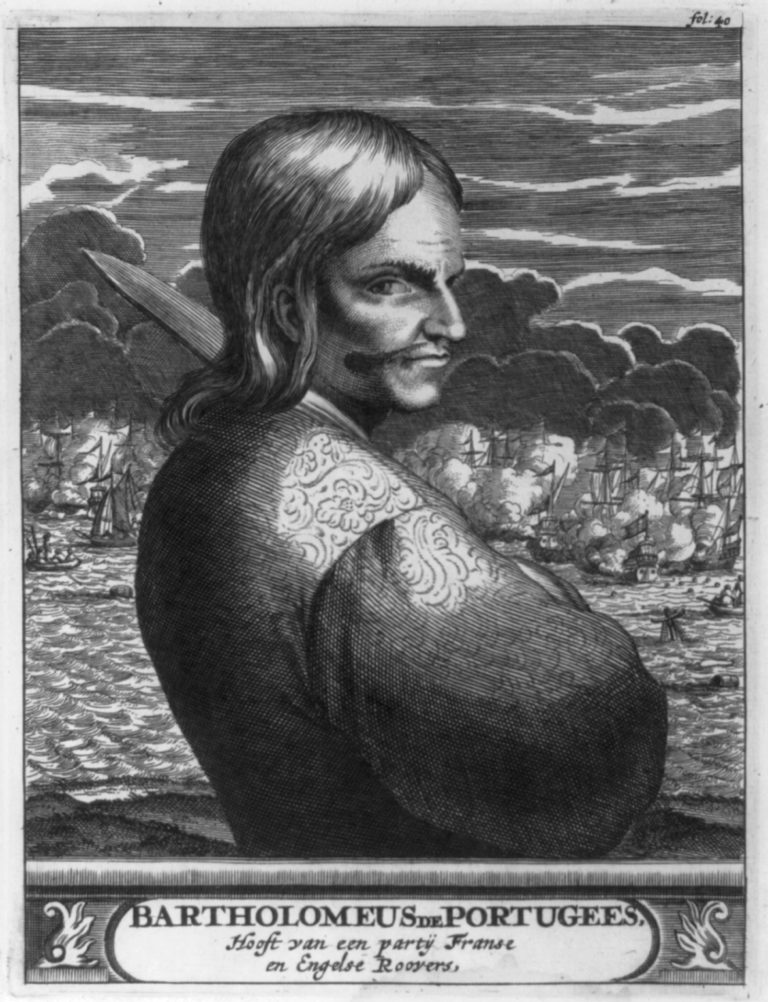

If Exquemelin took a certain glee in recounting pirate adventures, the book’s images underscored the pirates’ ferocity and masculine brazenness. The original 1678 Amsterdam edition presented dark, vivid portraits and “action” images of fights, battles, and torture. These portraits particularly established a visual repertoire that influenced all subsequent representations of pirates. The first of these provides us with a key to the images’ success. Bartholomeus de Portugees (fig. 1) is an iconoclastic figure, encompassing everything from menace to heroism. The anonymous engraver has rendered him with an immediacy that builds on but ultimately goes beyond the text’s breezy clip. He glowers at the viewer as if annoyed, distracted from his real purpose of watching his crew destroy a harbor full of Spanish ships. His drawn sword suggests his imminent participation in the attack; his dispassionate expression and the resolute set of his jaw signals an utter disdain for the panicked men glimpsed drowning in the foreground. Indeed, the image even hints at a smile on his face, although the viewer senses that one’s eyes might be fooled by the turn of his tidy mustache. His appearance is a mix of contradictions: his lack of a wig, matted hair, and crudely heavy brow assure the viewer that this is no gentleman, yet he wears a rich, billowing damask coat with a generous sleeve. His posture is reminiscent of Titian’s influential Man With a Blue Sleeve(ca. 1510), an image that had already inspired Rembrandt’s 1640 Self-Portrait at the Age of 34, among others. But Bartholomeus’s facial expression is radically different from that of either Titian’s or Rembrandt’s figures, granting new meaning to the posture. If Titian used it to convey his subject’s beguiling self-assurance and stability, Exquemelin’s anonymous engraver evoked his thoroughgoing malice and twitchy energy.

Despite the fact that most of the sheath of Bartholomeus’s drawn sword is concealed by his body, numerous details remind the viewer of its presence. All of the print’s movement directs the viewer’s gaze up the blade—beginning with the angle of the subject’s elbow and shoulders and mirrored in the shape of his nose, the shadow of his cheekbone, and the set of his jaw. Even the clouds of smoke from the burning Spanish ships in the distance become darkest and most ominous near the sword’s tip. Portugees’s exposed blade epitomizes danger, ruthlessness, prowess. Contemporary military portraiture often featured armed men but virtually never men whose swords were drawn and erect. The Dutch artist Van Dyck’s 1624 painting,Portrait of a Young General and his Portrait of a Commander in Armor, With a Red Scarf (ca. 1625)—again, images likely in circulation in Amsterdam in 1678—both evoke masculine power but not the brutal volatility of Bucaniers‘s illustrations. Each of the book’s subsequent portraits, including those of Rock. Brasiliano and François Lolonois (figs. 2 and 3), returned to similar themes: the scowl and heavy brow, the drawn sword (here the bright silver of Lolonois’s blade seems to shimmer against the image’s action), and a detached perspective on their victims’ suffering.

The images must have been potent: the same copper plates were recycled and reused for nearly thirty years after their initial use. Shortly after the book’s 1678 appearance in Amsterdam, the text was translated into German and issued by a Nuremberg press in 1679. The German printer paid to purchase the original engraved copperplates and transport them approximately 670 kilometers inland—potentially a very expensive undertaking since transportation and escort costs, tolls, and border levies increased an item’s cost considerably. Transport overland between Frankfurt and Nuremberg, for example—less than half the distance from Amsterdam—ballooned a book’s cost by an average of about 25 percent. The German printer had to worry that the plates would be damaged in transit, for even the smallest scratch in the copper would appear in subsequent prints; then he had to contract with an engraver’s workshop to find someone with the skills and equipment to print the images, as copperplates required a special press with extraordinary weight to coax the ink out of the plates’ tiny, subtle cuts. In addition, the pressure imposed by a copperplate press was so extreme that plates wore out; depending on the quality of the copper and the particular pressure of the press, this could occur as quickly as after only 125 impressions. In such cases, printers hired engravers to recut the plates by using a tool to carefully trace over and deepen the plates’ worn lines and restore their ability to produce sharp images.

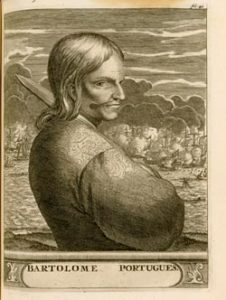

The move to Nuremberg did not mark the end of the plates’ travels. By 1681, they had been sold yet again to appear in a Spanish-language edition of the text produced by Lorenzo Struikman, a Cologne printer (located some four hundred kilometers back en route to Amsterdam from Nuremberg), who sought to take advantage of eager Spanish reading audiences willing to pay for high-quality books imported from Northern Europe. Struikman had the copperplate printer rub out the original Dutch text and retool the pirates’ names below—with mixed success, for we can still see the shadow of the original writing (fig. 4). He also used the Dutch plates for his second edition, issued a year later when the first quickly sold out.

It was the popularity of the Spanish-language edition that gained the attention of London printers. When William Crooke produced his own edition (translated from one of Struikman’s Spanish copies), he too decided that the original engravings were so superior that he purchased them. Yet again, the plates traveled nearly six hundred kilometers from Cologne across the Channel to London. This time the printer did a poor job reproducing the engravings, which appear decidedly worn (fig. 5) and display the shadow of the rubbed-out Dutch caption even more clearly. But the quality of its prints did not prevent the book from selling out; within two years Crooke produced two more illustrated editions of much higher quality, indicating that he had either found someone to retool the plates or located a more experienced copperplate printer to produce the prints (or both). By 1704, the plates had changed hands twice more to appear in four more London editions. Considering that the Dutch plates were ultimately used to produce nine separate editions of a consistently popular book, we might conservatively guess that at least five thousand copies of the book appeared with these images inside—and, more liberally, perhaps as many as thirteen thousand—radically testing the ability of copper plates to produce legible images.

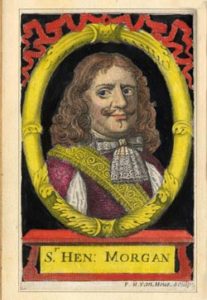

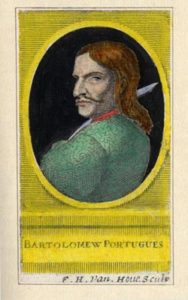

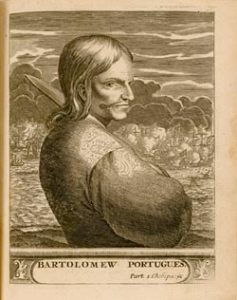

It was highly unusual for a single set of plates to appear in so many editions produced in so many different cities: later in the eighteenth century, printers would save themselves the costs and risks of purchasing worn plates by hiring local engravers to copy a book’s images. Why didn’t these printers do the same? I suspect the answer lay as much in the high quality of the original plates and the superior reputation of Dutch engraving as in English engravers’ poor reputations and the excessive time it took to produce a single engraving. When a different London printer, Thomas Malthus, produced his own, revisionist version of Exquemelin’s Bucaniers in 1684—a volume that described the recently knighted Henry Morgan in far more flattering terms than as the sadistic antihero of Exquemelin’s telling—he hired F. H. Van Hout (possibly a Dutch émigré) to copy the portraits. To help buttress Morgan’s reputation, Van Hout produced a heroic frontispiece portrait (fig. 6) that copied the Dutch version but eliminated the background view of a dramatic sea battle in order to festoon Morgan’s bust with elaborate curlicues and a heavy oval frame. Likewise, his version of “Bartholomew Portugues” (fig. 7) removed Portugues from the midst of battle. To be sure, such stripped-down images would have been easier and speedier for Van Hout to produce, the better to compete with the other editions of the book circulating in London. Whether Malthus’s flattering account of Henry Morgan proved unconvincing or his indifferent images simply failed to compete with the Dutch originals, his version of Exquemelin’s Bucaniers appeared in one edition alone; meanwhile, the Dutch plates continued to accompany the original text until 1704.

As Bucaniers of America circulated through Europe, one engraver after the next embroidered on the same themes of ominous danger and masculine bravado that originated with the 1678 illustrations. Take the Paris printer, Jacques Le Febvre, who produced four editions of Exquemelin between 1686 and 1705. With only three images (none of which were portraits) in the book, the French printer did not attempt to reproduce the visual richness of the original; but the images he commissioned nevertheless built on the themes laid out in the Dutch plates. His engraver, Bouttals, incorporated aspects of the original pirate portraits into a new title page. Where the Dutch title page relegated the theme of violence primarily to the tiny scenes that circle the central images (fig. 8), Bouttals opted for less peripheral detail in favor of a more focused center of action and vivid figures on either side of the calligraphed title. His buccaneers are hidden by shadows, avoiding the viewer’s gaze (fig. 9). He seems to have borrowed from earlier portraits of Portuguees and Lolonois to depict one pirate with shabby clothing signaling his subjects’ low origins (as in the images developed for the 1741 London edition [figs. 10 and 11]). In Bouttals’s interpretation, the pirates’ physical threats appear far more menacing than in the Dutch title page, with swords ready to slash throats and pierce breasts and the pirates’ visages intent on inflicting harm and less inclined to ineffective posturing. The European who looks hopelessly to the viewer for help in Bouttals’s version is about to suffer more than death, for the pirate appears prepared to level a far more serious kick to the groin than did his counterpart in the Dutch title page.

Kicking a man in the crotch while slashing his throat might seem gratuitous—adding insult to fatal injury. In fact, these kicks were emblematic of the kind of violence pirates inflicted. After all, a Lolonois or a Brasiliano challenged their victims’ manliness not merely by rendering them prostrate but by stealing their goods. Buccaneers’ rise from obscurity and the lowest social orders to possess terrific riches, their strict loyalty to one another, and the rough equality they cultivated depended on the fact that they targeted the wealthiest ships and cities for attack. These class inversions did not pose an open threat to the English social order (as paeans to the pirates’ Englishness attest). But the comparatively ragged clothing of the pirate and his conquest over the elegant European would have stood out to readers as a sign of the inverted hierarchies and alternative masculinities that could exist in the imagined locale of such exotic Caribbean islands as Jamaica and Tortuga. It signaled that not all men needed to follow the same path.

The fact that Bouttals had them lay their riches at the feet of the symbolic figure of America, the Indian princess, rendered these men even more dangerously capricious by suggesting that they robbed Europe to give to no one in particular—or worse, to savages. The image conveyed the extent to which they had stepped outside the norms of European manhood. Unlike the figure of Britannia, who represented the justice and law of England, the “naked” Indian princess evoked a cruder form of order. This image figured America as a place where riches could not be utilized in the rational fashion Europeans idealized. Exquemelin’s descriptions of pirates’ propensity to steal and then lose vast riches signaled their separation from the ideal of financial moderation as well as manly self-control.

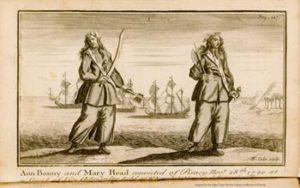

The central motifs in the Dutch images had a staying power that extended beyond the many editions of Exquemelin’s Bucaniers. By the time Captain Charles Johnson’s immensely popular General History of the Pyrates appeared in 1724, the London engraver B. Cole drew from a ready supply of pictorial conventions, including scowls, drawn weapons, and dramatic action. Even though Johnson’s text adopted a sternly moralistic tone almost entirely lacking in Exquemelin’s account, Cole’s illustrations—particularly the one of Anne Bonny and Mary Read, the female pirates who earned such infamy during the 1720s—evoked prurient delight with pirates’ sexual and violent transgressions. The portraits highlighted the pirates’ caches of weapons, depicting Blackbeard with not just an erect, drawn sword but six holstered pistols and a second sword seen hanging in its sheath between his legs; the women pirates hold both hatchets and swords (figs. 12 and 13). In fact, when another London printer issued a cheap reprint of the book the following year, he replaced the three copperplate engravings with ten woodcuts depicting each of the pirates in successively more provocative poses displaying their manly bravado and cocky virility (fig. 14). By midcentury and later, dozens of cheap woodcut-illustrated editions almost identical to the London original emerged from presses in Glasgow, Birmingham, Worcester, and elsewhere (fig 15). Pirates had become synonymous with ferocity, weaponry, action, and, more obliquely, sexual danger.

Although erect swords and angled hatchets might appear phallic to twenty-first century viewers, not all eighteenth-century readers would have granted the images such connotations. In fact, considering the overriding subject of physical violence in Johnson’s text, we might see such images as primarily emphasizing the pirates’ capacity to torture innocent bystanders as well as armed opponents. And yet considering that the books’ illustrations were partnered with a heightened interest in the pirates’ sex lives in the text, perhaps readers would see the images as phallic after all. Johnson lavished attention on the pirates’ marriages, interracial sexual liaisons, multiple children, and most of all their perverse or barbaric sexual violence against women. He left little doubt that a good number of the pirates’ outrageous acts had been sexual in nature. Captain Edward England and his crew, for example, often combined rape with pillage: they forced women “in a barbarous manner to their lusts, and to requite them, destroyed their cocoa trees and fired several of their houses and churches,” while Edward “Blackbeard” Teach forced his “fourteenth wife” to “prostitute herself” to members of his crew as he watched. Blackbeard was not the only pirate who refused to limit himself to a single wife in Johnson’s account; nor was he the only one to mistreat his wives to confirm his power over them. Captain Henry Avery and his crew “married the most beautiful of the Negro women, not one or two, but as many as they liked” in Madagascar, “so that every one of them had as great a Seraglio as the Grand Seignior at Constantinople.” Less sedentary pirates settled for perpetual “whoring” with women throughout the Caribbean and elsewhere. If Johnson had intended to debunk romanticized pirate myths that had circulated in London during the prior decade (as he promised in the book’s early pages), he went on to establish a new mythic canon revolving around the pirates’ sexuality and malevolent fearlessness, which would remain in print for over a century.

Such representations of male pirates are particularly thrown into relief when considered alongside Johnson’s portrayals of female pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read, depictions that placed even stronger emphasis on the women’s gendered identities and sexual lives. Johnson introduced the women dramatically: before informing his readers of the existence of female pirates, he described a scene in the Court of Admiralty that was trying and convicting a large number of men for piracy in Jamaica in 1721. Two of these were “asked if either of them had any thing to say” to mitigate the death sentences they faced. They stunned the court by revealing themselves to be women and announcing that “their bellies, being quick with child” should make them eligible for stays of execution—which they received. As it turned out, the women’s cross-dressing went beyond pirate costumes. Both had been born illegitimately and had found, throughout their lives, a degree of economic freedom in an array of male disguises. Still, Johnson focuses not on the material benefits of cross-dressing but on titillating (and almost Shakespearean) moments of sexual confusion. As a young recruit in the army, Read fell in love with one of her officers, continually risking life and limb to be near him—behavior that her peers found “mad” and perplexing. She was so distracted by her love that she neglected her duty: “it seems Mars and Venus could not be served at the same time,” Johnson comments philosophically. Read eventually contrived to let her officer “discover her sex” one night as they lay together in a tent. Even more risqué was the moment when Bonny and Read met aboard a pirate ship, each in full disguise. Taking Read “for a handsome young fellow,” Bonny took “a particular liking to her” and secretly revealed that she was a woman—presumably to solicit sex. Johnson allows the sexual confusion of the scene to play out for his readers’ enjoyment, delaying its resolution. He even indicates that Read at least considered the possibility of playing the paramour to prolong her ruse. But “knowing what she would be at” if she did not come clean “and being very sensible for her own incapacity” to play the man for Bonny’s sake, she revealed the truth to Bonny’s “great disappointment.” Eventually the two women confided in Bonny’s “gallant” Captain Jack Rackham as well, as he had threatened to “cut her new lover’s throat.” Replete with cross-dressing, sex (consummated and otherwise), and a disdain for gender propriety, these biographical vignettes emphasize exceptional choices and behavior and, in doing so, closely resemble those of male pirate characters. Narratives of both men and women cast pirates as outsiders who reject gender conventions and flout sexual propriety.

The book’s images of Bonny and Read reflect engravers’ struggle to portray the mix of conflicting gender codes and disguise represented in Johnson’s volume. In the original 1724 edition they are portrayed with flowing hair crowned with feminine caps and dressed in improbable loose-fitting culottes that suggest wide hips and possibly even the “big bellies” that saved these women from the gallows (fig. 13). Of course, if they had truly worn such outfits, they would have fooled no one as to their sex; the costumes help readers imagine the women’s disguise while confirming their sex. Yet the engraver did not hesitate to represent them as prone to the same ferocious violence as their male counterparts. Armed with swords, hatchets, and pistols, and angry facial scowls, Bonny and Read bear little resemblance to the women commonly idealized in contemporary English culture and literature. Cole’s images were so evocative that they were copied in virtually every one of the dozens of English reprints of the book, even those that featured only a small number of cuts.

When the book was translated and published in Amsterdam in 1725, the new Dutch engraver borrowed from Cole’s images and improved on them. He portrayed them in breeches, heavily armed, and striking jaunty and mildly threatening poses. Most striking, he sexualized them. The women’s long tresses, open shirts, and full breasts confirm their sexual appeal and availability. They have become Venuses with muscle and an almost pugilistic readiness for action (figs. 16 and 17).

How did readers make sense of the female pirates who fought and fornicated their way across the pages of Johnson’s Pyrates? It is tempting to imagine that readers might have seen them as strong rebels and volatile romantics, prototypes of a form of active female agency in matters of economics, sex, and self-protection that would contrast sharply with the passive women of domestic fiction. From another vantage point, Read’s and Bonny’s cross-dressing may have signaled that transvestism (which appeared in many forms in early modern Europe and America) offered promises of a more inchoate and far-reaching personal transformation and liberation. Yet again, perhaps vivid illustrations of erect swords and tales of nearly egalitarian comradery produced homoerotic fantasy, at least by some.

But our interpretations change if we focus on the full range of probable readers—not only the female or same-sex oriented male readers who sought out tales of gender or sexual transgression but also the middling and elite men who used their disposable income to purchase expensive illustrated books and patronize social libraries. Men who enjoyed comfort, wealth, and position had little need for liberation per se, as they were, by any measure, already the most “free” in society. Escapism was different: reading these tales might have helped men imagine escaping from their social, economic, and sexual responsibilities to live far more freewheeling lives and express their basest instincts. Of course male readers might well have found representations of pirates appealing. But liberating? If we consider the full range of probable readers, as well as the spectrum of subjects covered in books like A General History of the Pyrates—which included female pirates and hints of homoeroticism but focused most of all on gleefully brutal depictions of men unbound by gender expectations of sexual self-control and obligations to dependents—we come closer to understanding why hyper-gendered portrayals of pirates had such lasting appeal from the eighteenth century to the present and why specific conventions for representing them have become so ubiquitous.

If Exquemelin’s Bucaniers of America had been less popular, we might be skeptical of its role in establishing lasting conventions for representing pirates. But books from Captain Charles Johnson’s General History of the Pyrates to twentieth-century films continued to build on motifs established in the late seventeenth century. The themes of manly adventure, gender transgression, erotic violence, and moral ambivalence have recurred with such regularity over these centuries by successive writers and illustrators that we can’t help but see how early modern print culture came to rely on such conventions for selling books.

A counterexample from our own era underscores this point. Perhaps the best testament to our unwillingness to break from conventional views of pirates came during the spring of 2009 when, due to a series of impressively successful attacks, the subject of piracy off the coast of Somalia moved from newspapers’ back pages to the fore. In April, we were presented with a series of photographs of improbably small motorboats filled with skinny Somali men in t-shirts with mischievous grins on their faces. But for those photographs and film footage, it might have been easy to develop news stories that conformed to long-established responses to piracy. Surely we might have admired the audacity of men who used tiny boats, limited manpower, and very big guns to capture and ransom off ships belonging to the most powerful nations in the world. The story had all the elements necessary to tie the Somali pirates to a long history of daring attacks. The fact that they hailed from one of the poorest and least powerful nations on earth might only have elicited more wonder. But the photographs displayed men whose appearance ran counter to expectations conditioned by a long tradition of images. Journalists seemed almost audibly disconcerted as they sought a gratifying narrative for the story; in the end, they merely decried the Somalis’ thievery and made weak allusions to international terrorism.

What would it have taken for us to identify with the Somali pirates, as readers of Exquemelin and Johnson identified with the pirates they described? What kind of narrative would have enabled us to incorporate the Somalis into the pirate stories we have inherited? One can’t help but lament their lack of a good publicist. We have not yet seen the author who will characterize them as would-be Robin Hoods up against intractable Western powers or perhaps play up their heroic roles against the backdrop of Somalia’s lack of social and governmental order. At the very least new narratives will require a costume change. If tricornered hats would appear over the top, we need to see them in clothing other than the t-shirts that only exaggerated the Somalis’ slight frames and third-world poverty. That new narrative may be coming. Already photographs have appeared depicting them with machine guns held erect; visual representations featuring cocky poses and dramatic clothing will not be far behind, inviting newly enticing tales to captivate readers. This pirate story isn’t over yet. We can look forward to its gradual incorporation into a tradition of representing pirates as seductive antiheroes—men and women who have evoked that powerful combination of fantasy, revulsion, and identification so successfully for three hundred years.

Further Reading:

Some illustrations and pages from the original edition of Alexandre Exquemelin’s Bucaniers of America (Amsterdam, 1678) are available online by the Library of Congress; meanwhile, Captain Charles Johnson’s General History of the Robberies & Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates (originally published London, 1724) is still in print.

For recent histories of real-life pirates, see Marcus Rediker’s Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates, and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700-1750 (Cambridge, 1987) and his Villains of All Nations: Pirates in the Golden Age (Boston, 2004), as well as Virginia Lunsford’s Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands (New York, 2005). To accompany his review of Peter T. Leeson’s new economic history of piracy, The Invisible Hook, in the September 7, 2009, issue of the New Yorker, Caleb Crain offers a list his sources on pirates. On gender and sexuality in seafaring, see Margaret S. Creighton and Lisa Norling, eds., Iron Men, Wooden Women: Gender and Seafaring in the Atlantic World (Baltimore, 1996) and Hans Turley, Rum, Sodomy and the Lash: Piracy, Sexuality, and Masculine Identity (New York, 1999).

On the history of books and reading, see Adrian Johns’s The Nature of the Book (Chicago, 1998). See also Roger Gaskell’s “Printing House and Engraving Shop: A Mysterious Collaboration,” in The Book Collector 53 (Summer 2004): 221-24; Sheila O’Connell’s Popular Print in England (London, 1999); and Joseph Monteyne’s The Printed Image in Early Modern London (London, 2007).

Finally, the full transcript of Saturday Night Live‘s 1979 skit, “The Adventures of Miles Cowperthwaite,” is available online.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.1 (October, 2009).

Carolyn Eastman is assistant professor of history at the University of Texas, Austin, and the author of A Nation of Speechifiers: Making an American Public after the Revolution (2009) as well as essays in the William and Mary Quarterly, Gender and History, and American Nineteenth-Century History.