Soldiers’ Tales: “What Did You Do in the War, Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandpa?”

In 1818, a good war story could fetch you eight dollars a month–and survive you by two hundred years. In the second decade of the nineteenth century, when Congress first granted pension benefits to Revolutionary War veterans from the enlisted ranks who were “in need of assistance from [their] country,” grizzled and destitute exprivates began flocking to their county courthouses to claim their due. Documentation, being rare, wasn’t required, but stories were: to prove their service the veterans were expected to regale the honorable justices with forty-year-old memories of military actions, to impress them with the names of commanding officers, and to supply them with details on places and dates, all of which were taken down on paper for the claimant’s signature or mark. To this day in the National Archives in Washington, thousands of old soldiers remember the war of their youth.

Two of those old soldiers were ancestors of mine. Both William Wharton and Ralph Collins had arrived in the colonies shortly before the war, both ended up in Kentucky soon after it, and both were chronically, sometimes operatically, unlucky in their pursuit of happiness. Their war stories, however, suggest they found very different ways to handle their disappointments. While one forebear apparently forbore talking about himself even when he had tales of high adventure to share, another revised the story of his very low military escapade with such gusto and such success that a version of it was still being actively told a nearly century later. One, it seemed, felt his unhappiness deserved no stories. The other told stories to earn his happiness.

The unhappiest of my ancestors, my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather William Wharton, couldn’t seem to hang onto anything. Not his freedom; he may have arrived in Maryland as a transported convict. Not his land; soon after the Revolution he bartered away the military warrant his painful army service had so painfully earned him. Not his civic responsibilities; he was always on the run from the taxman. Not even his children; in 1805 exasperated officials in Pendleton County took his two youngest daughters away and bound them out. By the time the pension act passed, seventy-one-year-old William Wharton was apparently so desperate he applied twice, submitting a statement to the county court in June 1818 and another, essentially the same, in September. In the financial inventory he filed two years later to confirm his need he added that he was supporting an illegitimate orphaned granddaughter, that he was “very infirm and totally incapable to pursue” his work as a weaver, and that his only asset was a forty-five-dollar horse. Persuaded of his indigence, the government allowed him the standard private’s pension of eight dollars a month.

Although William Wharton’s pension claims lay out a history of losses, they remind us that in spite of the odds against it, he managed to keep hold of one precious possession: his life. This unhappy man had apparently been either phenomenally skillful or phenomenally lucky during his seven years as a private in the Eighth Pennsylvania. If he was indeed with his regiment whenever he was supposed to have been–a reasonable if unverifiable assumption, since the skimpy contemporary records confirm a period of service but not his whereabouts during that period–then he managed to survive not just the nasty battles of Brandywine and Germantown but also the action at Paoli that the Americans, with reason, called a massacre, not a battle. If he was with his regiment, then he also numbered among the rare genuine members of what would, over the years, become the most honored band in the Revolutionary army, as well as the most overcrowded. He was (or at least the Eighth Pennsylvania was) among the eight or ten thousand soldiers who actually served with Washington at Valley Forge during that awful winter of 1777-78 and survived the hunger, cold, and disease that killed thousands more of their comrades before the dawn of spring.

Even though America’s romantic re-engagement with its past hadn’t yet hit high tide, by the end of his life William Wharton had plenty of incentive to tell stories of wartime adventure, sacrifice, and courage. A nation still too fresh and hopeful for a history needed heroes, at least, if it was to succeed in figuring out who and what it was, and heroes of the Revolution were naturals to fill the bill: they had fought in a great cause; they had won a great victory; they had fathered a great nation; and in the early years of the new century, they were beginning to die off.

The greatest of these heroes, of course, was George Washington, dead (and Weems-deified) two decades earlier. Washington’s reputation had become so lustrous that many who could not legitimately claim its reflected glow simply appropriated it, spinning yarns of how they or their fathers had known Washington or served with Washington or–as the story would go about another of my ancestors from a different branch of the family–had left bloody footprints in the snow during doughty service as Washington’s courier at Valley Forge. (In fact “Tough Daniel” Maupin did not enlist until 1781 and never left Virginia, but he was far from the only claimant to those iconic tortured feet.) But by the time the country decided to deliver pensions to indigent soldiers, Revolutionary herohood was actually open to almost anybody who had picked up a musket. Even some of the most ordinary soldiers were publishing narratives of their own experiences in which they presented themselves as authentic, conscious, and worthy actors in a drama whose outcome they helped determine.

But when he filed for a pension, Wharton, whose regiment had fought with Washington, did not bother to say he had seen action with the great man.

“Early in the beginning of the war, and amongst the first Recruits of the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment,” he said in his pension application, he’d enlisted in Westmoreland County under Colonel Aeneas Mackay (who, along with dozens of his ragged men, died early in 1777 during their march over the wintry Alleghenies to join Washington in New Jersey), and had re-enlisted when his first three-year stint was up. By then he had a new company captain, too, because the first, he recalled tersely, had been “killed by Indians.” Wharton declared he had been “mostly engaged in the spy or scouting service on the western waters”; the only specific action he mentioned was “the taking of the Muncey Indian town” on the upper Allegheny River in 1779 after the Eighth’s return to Fort Pitt. Though it afterwards rated barely a footnote in the history books, that brief expedition under Colonel Daniel Brodhead was a rare romp for the Eighth Pennsylvania; the regiment took no casualties and spent most of its time burning the Indians’ villages and hacking up the Indians’ corn. Offered the wide-open opportunity to talk about his military service, former Private Wharton entirely neglected to mention his presence at the epic battles near Philadelphia and at the wintertime camp at Valley Forge.

It might have been old age that dimmed his memory and robbed him of a garrulousness that likely tired his grandchildren. It might have been the diffidence of a habitual loser unaccustomed to telling officialdom something good about himself. It might have been a posttraumatic reluctance to delve too deeply into old memories of terror and pain.

Or even as some old veterans boldly accepted the nation’s invitation to refashion themselves as heroes, Wharton may have remained firmly enmeshed in more traditional ideas about the ordinary individual’s right–and ability–to control and narrate his own fate. He could have believed those long-ago years spent being harried and clobbered by enemy invaders were not particularly important or interesting, not especially different from the rest of a long life spent being harried and clobbered by creditors and courts and tax collectors and daughters pregnant out of wedlock. Unlike those marquee battles his unit had barely survived, after all, the Indian skirmish William remembered for forty years had been a resounding victory for his side.

In fact, Wharton probably remembered every victory he’d ever participated in, whether personal or military; victories were probably easier to count than his children. Unlike his many children, however, for whose creation, at least, he could take credit, history remained entirely outside his control. America’s great founding epic had been to Private Wharton just a dirty job that brought him only servile misery, a very tardy eight dollars a month, and no closer to happiness than he’d ever been, or expected to be. Some stories are suppressed; some are embroidered or altered. But some–including many of the ones that to a historian with hindsight seem irresistible–simply feel more like life than stories to those who inhabit them most closely.

Ralph Collins’s prospects seemed no more promising than William Wharton’s; he did, after all, choose William’s oldest daughter to marry, and he had problems of his own with the tax collector, which in 1790 landed him on the roll of defaulters in King and Queen County, Virginia. By the time he took young Margaret to wife in 1803, Collins was a veteran twice over, though neither time entirely by choice. The young and illiterate immigrant had been drafted into the Revolutionary army in the closing months of the war, but found postwar Virginia so unappreciative of his talents that in 1791 he resorted to an expedient that testifies to the leanness of his options: enlistment as a short-term “levy” in the tiny and disreputable federal army Congress had authorized for duty on the Ohio frontier. The pay was lousy–a private like Collins cleared two dollars a month after deductions for his clothing and supplies–but at least he was supposed to get steady meals, and he got himself whisked beyond the reach of the tax man besides.

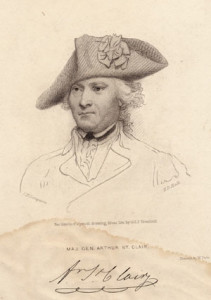

He also got himself whisked straight into the battle that is still considered the American army’s worst defeat ever, the Indians’ best day ever against U.S. troops. In a single day marked by a string of misfortunes, iniquities, and idiocies, most of the U.S. military force was lost on the banks of the Wabash in a battle so awful it earned the rare distinction of being named not for its locations but for its loser: St. Clair’s Defeat.

In the fall of 1791 Arthur St. Clair, the new governor of the Northwest Territory, took command of a motley group of local militiamen, six-month levies, and nearly all of the U.S. regular army on an expedition north from Fort Washington near the village of Cincinnati. The stated goal was to build a chain of forts all the way to the Miami Indian towns for the purpose of “awing and curbing” the local tribes who were continuing their bloody resistance to white settlement north of the Ohio. The mission was hexed from the start. The secretary of war had figured that three thousand men should be plenty, but even though enlistments had fallen far short, there was so little flour on hand that the men were on short rations most of the time. The flimsy tents welcomed in the wind and rain, the clothing supplied by an inept quartermaster disintegrated on the men’s bodies, the gunpowder had been soaked in a riverboat accident, and nobody was getting paid. “March” sounds too festive a term by far for how this army moved: hacking its way with bad axes through forest and thicket, hauling the big field guns through swamp and mire, prodding the drooping baggage horses, the column might, on a good day, lumber its way five or six miles forward. Everyone suffered in the constant rain and sleet, but St. Clair himself was so tormented by gout and what he called his “rheumatic asthma” that he couldn’t endure the saddle and had to be ignominiously lugged on a litter.

Few of the men seemed any more promising as fighters than their plump and prostrate general. Colonel Winthrop Sargent, the notoriously haughty adjutant general, was openly contemptuous, dismissing most of the corps as “the offscourings of large towns and cities; enervated by idleness, debaucheries, and every species of vice . . . An extraordinary aversion to service was also conspicuous amongst them.”

Ralph Collins shared that aversion to service. After a journey of 480 miles by foot and riverboat from Winchester, Virginia, Collins and his companions arrived at Fort Washington on August 29, 1791. Almost immediately they hit the road again–or rather, they made the road, chopping their way eighteen miles in three days to the banks of the Great Miami, where they were set to work building a fort. There, Collins lasted about a week. The orderly book of Adjutant Crawford shows that on September 20 Collins and nine others were court-martialed for desertion and sentenced to one hundred lashes each, the maximum permissible corporal punishment.

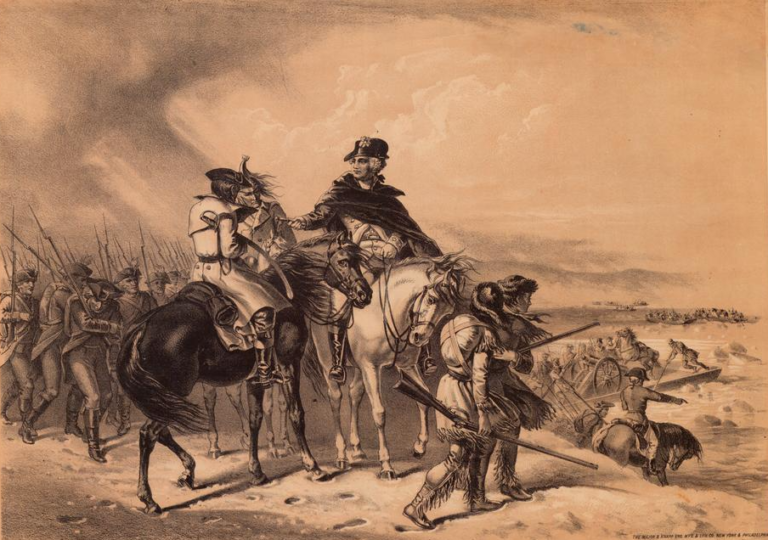

The expedition continued to toil north, and continued to leak men, as deserters wilier than Collins slipped away night after night. On November 3, two months and one hundred miles out of Fort Washington, the fourteen hundred or so remaining soldiers, servants, followers, and hangers-on stopped for the night at an old Indian campground perched above the banks of the Wabash River. Early the next morning, not long after reveille and before the sun had quite risen, some sharp ears caught a peculiar noise whose meaning soon became appallingly clear: it was the war whoops of one thousand warriors from a number of tribes, led by Little Turtle of the Miamis and Blue Jacket of the Shawnees, who were surrounding the camp.

It was not a battle; it was carnage. The fierce and determined Native warriors knew how to use the woods and ground for cover while constantly moving, never shooting from the same place twice. With ruthless efficiency they concentrated their fire on the officers, most of who were on horseback and easily distinguishable by their gaudier dress. Left leaderless, the green troops had neither the skill nor the grit to stand up to a massive surprise assault and most simply milled about in panic. When a retreat was finally ordered, groups of soldiers managed to escape by fixing their bayonets and rushing through a line of attackers too surprised at the sudden outburst of bravado to stop them. Ahead of the exhausted and shell-shocked survivors–many of them bleeding, hobbling, clamping their hands tight over jagged edges of oozing wounds–lay a hundred-mile slog through the rain back to Fort Washington. There they would find no room to sleep, nothing to eat, and not much to do other than to go to Cincinnati and get drunk. Which they did.

In the three-hour battle as much as half of St. Clair’s force had been killed and at least another quarter wounded, more than half of his officers had become casualties or gone missing, and most of his equipment and provisions had been lost. Among the Americans killed or captured were dozens of women and children, family members who had accompanied their men. Estimates of the Native American dead ranged from 150 down to twenty-one.

Ralph Collins’s unit, the First Regiment of Levies under Lieutenant Colonel William Darke, was in the thick of the action and endured a high proportion of the casualties. Colonel Darke himself, who emerged as something close to a hero in the action, led (and survived) two game but futile bayonet charges. Again and again, as Darke reported on November 9, 1791, in a letter to President Washington, he had tried to rally his stunned troops on the field, but they “would not form in any order in the confution,” and “the whole Army Ran together like a mob at a fair.” Some of the officers had behaved bravely, Darke allowed, as did a few of the men and even one resolute packhorse master; it was the levies who suffered most of the casualties. “And indeed,” Darke told Washington with a brutality only slightly excusable by his grief over his own mortally wounded son, “many of [the levies] are as well out of the world as in it.”

How the particular levy I’m interested in managed to stay in the world through the awful battle we have no clue. Ralph’s service record in the National Archives reports no wounds, nor did he “los[e] his arms in action,” the mishap (or more likely the choice, the faster to run or the lighter to travel) that was charged against the meager pay of so many of his surviving comrades. All his record says is that he was discharged on November 11, a week after the action, leaving wide open the question of whether phenomenal soldier’s luck ran in the family–or whether the convicted deserter had made better use this time of his “aversion to service.”

But unlike his father-in-law William Wharton, Ralph Collins talked about his war, often. In the pension application he submitted under the modified regulations of 1832, when he was seventy-two, he made a point of telling the Grant County court that in addition to serving in the militia during the Revolution–when he had participated in the siege of Yorktown–he’d also taken part in “what is generall[y] known as St. Clairs Campain he was under Captain Dark for nine [i.e., six] months, and with him at the defeat of St. Clair.” He must have known that postwar enlistments did not count toward a pension, but as a short-term draftee during the Revolution he seems to have fallen just short of the required six months’ service. His story won him no pension.

Ralph Collins also shared his war stories with his children, who were themselves happy to spread the tale of their father’s survival in so dramatic and lethal a battle. In 1836, Ralph’s sixth child, twenty-three-year-old John Collins, emigrated with his new wife to what would become Scotland County, Missouri. John ended up making a very respectable life for himself as a self-taught judge and seems not to have kept in close touch with his Kentucky kin; his name was not even mentioned in his father’s 1847 will.

But in a local history of Scotland County published in 1887, the short biography of Judge John Collins, doubtless written with the collaboration of the subject, carefully mentioned not just his son the congressman but also his father the soldier who “took part in the battle in which Gen. St. Clair was defeated.” As inexplicable as Collins’s own unscathed survival is the persistence of a story about a brief century-old battle fought by a man three hundred miles distant and forty years dead, a humiliating butchery of a battle redeemed by no heroics and won by the wrong side, a battle that possessed none of the historic luster of the Yorktown siege in which Ralph had also taken part and that had long since been eclipsed by the monumental conflict in which two of Judge Collins’s own sons had defended the Union, one at the cost of his life.

We do not know exactly what Ralph Collins had told his family about his war, though their enduring pride in his participation certainly suggests an emphasis on something a good deal nobler than one hundred lashes for desertion, something a good deal more complimentary than Colonel Darke’s report. So we can presume that whatever the tale, Ralph Collins had felt freer than William Wharton did to put his own mark on his history.

Knowing nothing about the characters of the two men, we can only guess at what made the difference. Time and sentiment doubtless had something to do with it. There is no record of exactly when Wharton died but it seems to have been right around 1832, that epic year when the coincidence of the death of the last Signer of the Declaration of Independence and the centennial of the birth of the sainted Washington helped inspire Americans into a peak of nostalgia for the heroic era that was so visibly slipping away. So in the final indignity to an undignified life, poor Wharton died just when his stories would have made him most interesting. Collins, on the other hand, survived by seventy-two years the shot heard ’round the world, and died a relic as rare as he was doubtless venerated.

But there seems to have been more to Collins’s mythology than mere survival, and in the lives of the children of Wharton and Collins lies a suggestive clue. William Wharton’s only son died before his father, leaving an impoverished widow, and William’s daughters neither loved more wisely nor chose more fortunately than their mother had: one was “sullied,” one left no trace past childhood, one married the unprepossessing Ralph Collins, and the last married a husband even poorer.

But Ralph’s children were different. John, the self-made judge, was not the only Collins offspring to leave his father in the dust. In 1850, John’s youngest brother, Joseph, a thirty-four-year-old farmer, reported a respectable net worth of two thousand dollars; ten years later he was worth more than three thousand, and by 1870 a handsome $12,575. Another Collins brother, William, valued his property at only three hundred dollars in 1850, but a decade later reported a tenfold increase in wealth. Their sisters Mary and Jane married into solid farming families, and Jane’s husband was elected twice to the state legislature.

Since much of his children’s success seems to have flowered only after his death, it could not have been their rising fortunes that emboldened Ralph into some ex post facto raising of his own. Perhaps the relationship between his stories and their happiness was something a bit subtler and more intricate. William Wharton’s children never did any better than their father had any reason to expect. But Ralph Collins, who from somewhere had found the self-assurance to tell his own story his own way, was in effect laying claim to his right to damn the Colonel Darkes of the world and to create not just a story but also a life of his own choosing. Maybe a man with the spunk to recalibrate the justice of his own deserts could provide the jolt of inspiration his children needed to believe they too could succeed in their pursuit of happiness. Maybe creating a family memory had the power to shape the family fortunes as well.

Further Reading:

The pension records are in the Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (Record Group 15) and Collins’s service record in the Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers who Served from 1784 to 1811, U.S. Organizations (Record Group 94), National Archives, Washington, D.C. Adjutant Crawford’s orderly book is in the William D. Wilkins Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. See also Lorett Treese, Valley Forge: Making and Remaking a National Symbol (University Park, Pa., 1995); Wiley Sword, President Washington’s Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman, Oklahoma, 1985); Winthrop Sargent, “Winthrop Sargent’s Diary While with General Arthur St. Clair’s Expedition Against the Indians,” Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 33 (July 1924): 237-73; Ebenezer Denny, Military Journal of Major Ebenezer Denny, an Officer in the Revolutionary and Indian Wars, with an Introductory Memoir (Philadelphia, 1859); Michael Kammen, A Season of Youth: The American Revolution and the Historical Imagination (New York, 1978).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.3 (April, 2004).

Andie Tucher, an assistant professor and the director of the communications Ph.D. program at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, is the author of Froth and Scum: Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and the Ax-Murder in America’s First Mass Medium (Chapel Hill, 1994). She is working on a book for Farrar, Straus, and Giroux about the intersections of history, memory, and story in one family’s four-hundred-year-long American experience.