Speed Reading in the Archives

“Wow, you must have a fun job! Archivists get to read everything in their collections, right?” This is a common question from individuals who want to know what I do on a daily basis as an archivist. I wish I could, and at one time I often did, read nearly every word of every document. Today, that luxury is just that—a luxury.

As Florence S. Marcy Crofut Archivist at the Connecticut Historical Society, I oversee manuscript collections numbering over one million items, accumulated since the institution was founded in 1825. Not surprisingly, given the extent and long period of collecting, these holdings are rich and varied, with locally and nationally significant items dating from the first experiences of European-Native American contact in Connecticut to present-day activities in the state’s cities and towns. However, it was not until recently that there was a trained archivist to manage those collections. When I arrived in 2004, one of my first major tasks was to inventory all of the manuscripts. The need to create a comprehensive record of holdings was given particular urgency by an impending heating, cooling, and storage renovation, which would require moving all of the manuscripts into temporary storage.

Over a third of the manuscript collections had no records in the online catalog; nine percent had no record at all; and ten percent had never been processed for researchers to use.

Armed with a pad of paper and several pencils, I systematically inspected every shelf in the manuscript stacks—43 ranges with approximately 1,276 shelves—which took a year to examine, record, and put into a searchable database of more than 18,000 records. That was while still doing my regular duties—answering reference questions and arranging and cataloging newly acquired collections. For the inventory, I opened every box and every volume to record very basic information, like the call number, the creator (author) of the collection, a brief title with dates (such as “Diary, 1750”), whether there was a record of this being a gift or a purchase, whether or not there was any organization to the collection, and a brief note on the size or extent (1 box; 30 volumes; 10 cartons). I also went through all 24 volumes of our accession records looking for manuscript gifts and purchases. Then I checked our card catalog and the online catalog (which has items added to the collection since 1984) to determine if researchers could find the collections using the tools already at hand.

What I found during the inventory both fascinated and appalled me. Some collections with obviously early documents had never been touched! The papers were still folded into little tri-fold bits, tied together with string or ribbon. Who knew what they contained? I was also fascinated at how carefully certain collections were cataloged, down to the item level—each letter had been individually described in the card catalog and sometimes in the online catalog. These records were for letters or documents related to individuals like Silas Deane, Oliver Wolcott and other great white men. Other important collections had no catalog record at all. This lack of access astounded me, even though several cataloging projects had preceded me, such as reporting collections to the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections, adding 96 finding aids (narrative guides) to Chadwyck-Healey’s National Inventory of Documentary Sources, OCLC (the national online database of library holdings) and 30 finding aids available on our website using special encoding, which was completed in 1999.

The inventory made it very obvious that over a third of the manuscript collections (5,542) had no records in the online catalog; nine percent (1,520) had no record at all; and ten percent (1,860) had never been organized (processed) for researchers to use. Unless you had access to browse the closed stacks, as I did, there was no way to know these collections existed, and there were no plans to provide non-staff access to the inventory.

The inventory did provide a good internal tool, allowing us to keep track of collection locations during the renovation project. The information it contained also allowed staff to draw upon previously untapped resources to answer users’ questions. However, we knew we needed to do much more to realize the potential of our holdings—no one outside the institution knew these collections existed. Fortunately, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) had recognized that similar processing and cataloging backlogs challenged archives all over the country, and had created a grant program designed specifically to address this challenge. In 2007, we submitted to NHPRC a proposal for a two-year project aimed at creating, with the assistance of a full-time Project Archivist, online catalog records for 900 of the largest 18,000+ collections in our library, plus more than 200 account books, one of our strongest yet little-known or used collections. That project was funded, and work began September 1, 2008.

The collections targeted for this project included records of the colonial era: Roger Wolcott (governor), Joseph Talcott (governor) and William Samuel Johnson (legal agent for Connecticut at the British Court from 1767 to 1771); documents from the Revolutionary War period: the papers of Oliver Wolcott Sr. (signer of the Declaration of Independence, delegate to the Continental Congress and General of the state’s militia), Jeremiah Wadsworth (Commissary General for the Continental and French armies) and diplomat Silas Deane; Civil War soldiers’ letters and muster rolls of Civil War regiments; and twentieth-century collections like the papers of Florence Crofut (20 linear feet), who was active in the Colonial Dames and helped preserve manuscript collections related to colonial Connecticut. If these collections were processed and cataloged in the usual fashion—unfolding each item, making sure everything has a date, copying newsprint so it does not continue to stain materials around it, putting fragile documents in clear Mylar protective sleeves, carefully reading each item, and organizing each item according to creator or recipient, and then by date—it would have taken at least six years, working full-time to achieve even minimal control over the collections. Other necessary functions, like assisting researchers, would have suffered.

Archivists love finding gems in collections they are processing, and the only way to do that is to read everything. However, in order to catalog 900 collections in two years, we had to implement what is called (and not necessarily widely accepted) in the archival field, “MPLP,” meaning “More Product, Less Process.” Using this approach, archivists do not remove every pin, paperclip or staple, do not copy newsprint, do not sleeve fragile items and do not read every item—only enough to get a sense of the type of document and the names that appear most frequently. The MPLP concept was originally developed by archivists at the Minnesota Historical Society, specifically for establishing control/creating access to modern, twentieth-century collections that already had some type of order and usually came to repositories in folders and boxes. Applying MPLP, the archivist processing the collection would make a list of folder titles, leave everything in existing containers, and create a collection level catalog record, which described the whole collection, and not individual items as my predecessors had done. What we proposed in our 2007 NHPRC grant application was applying the same approach to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century collections, which had traditionally been processed in the “old style,” or much more intensively organize down to the item level, catalog individual documents, and write a guide or finding aid in addition to the collection record. Item-level organization would require the archivist to look at every document in every folder and arrange those documents in some kind of order—usually chronologically. Individual items, such as a letter from Silas Deane found in the Oliver Wolcott papers, would, in the old style, have its own catalog record. A finding aid would provide a narrative biography of the creator of the collection (Oliver Wolcott) and another narrative, called a Scope and Content note, which would explain why the Silas Deane letter was in the Wolcott papers.

In contrast to twentieth-century papers, these earlier collections typically have no inherent organization since they were passed down from generation to generation, are rarely put into folders and certainly have no labels. The Town of Stonington records are a good example. The records were tied into bundles, each item in the bundle folded into thirds. One box might contain bundles dated from 1880-1885 mixed with other bundles dated 1840 and 1860. Because they were tied in bundles, we had no idea of the types of documents with which we were dealing. So, with volunteer help, we unfolded every document in the 24 boxes, made notes on the types of documents (mostly care for the poor and taxation) and organized them by year only. As a result, the collection grew from 24 boxes to 65!

MPLP is not embraced by the entire archival community. The primary concern is that using such a cursory approach will leave many important items “undiscovered,” to the detriment of researchers. There is also the possibility that personal documents requiring privacy restrictions could be overlooked. At CHS, Project Archivist Jennifer Sharp and I both found it initially rather difficult to adapt to the streamlined procedures dictated by the MPLP approach in the grant-funded cataloging project. The material we had to work with was more fragile than modern archives, implying the need for more care. Many collections had no logical order to them, requiring us to wade through documents in a folder or box in an effort to discern who and what the records were about. For example, the Meech and Huntington family papers (Ms 66235) consist primarily of the journals and correspondence of Preston, Connecticut, merchant and sea captain Appleton Meech (born 1790). It was not until we surveyed the collection that we realized these were mixed in with legal documents and financial papers of James Munroe Meech and Benjamin, Joshua and Andrew Huntington. Those additional individuals would not have been identified if we had not looked through the collection with some care. Most importantly, in order to write even the most basic catalog record, we still had to put our collections in context—determining where the people were located, when they existed, and perhaps what they were most noted for. For example, the collection of Baldwin family papers (Ms 67052) included letters between Elijah Baldwin, his son Elijah Baldwin Jr., and Elijah Sr.’s wife Hannah and their daughters Esther, Amy, and Hannah Baldwin Bishop. The only way to determine who was writing to whom was to gather the names that appeared on the signatures and the envelopes (if preserved with the letter), try to get a sense of the relationships, and then do some genealogical research to confirm those relationships.

Even though we are not scrutinizing every individual document, we still “discover” interesting items that no one currently at CHS knew we had in our collections. For example, in processing the extensive papers from the Clark and Hathaway families of New Haven, Connecticut, (Ms 98039) I was surprised to see detailed references to President James A. Garfield’s lingering death after being shot by Charles Guiteau in 1881. Frank wrote to My Own Dear Sweetheart, “The president had another taste of the knife today and it seems to have done him good. Such incidents keep me busy and anxious, and I so wish he was well and away from here, so that I could feel like getting away too” (August 8, 1881). I knew the collection contained the usual family letters containing news about daily activities such as who visited whom, the weather, etc., but I had no idea something as interesting as Garfield’s assassination would be included. Some research led to the discovery that the writer, Frank Trusdell, was a newspaper reporter most noted for his coverage of the Garfield assassination. While keeping watch at the White House until the President died, Trusdell wrote almost daily to his wife, Eugenia Hathaway Trusdell, in Haddam, Connecticut. About the same time as this discovery, I was reviewing scholars’ applications for New England Research Fellowships. D. Jaimez Terry, an undergraduate at the University of Maine, Farmington, was a successful applicant. His project was to research the changing public image of President Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau, by examining our holdings of Guiteau’s lecture transcripts. Now he had another resource, one neither he nor I had anticipated.

We occasionally get an “aha!” moment when we find the unexpected. In the 1852-1862 employee record book (Ms 73440) of Frederick Curtis & Co. of Curtisville (Glastonbury) we found reference to employee Albert Walker. We knew from his diaries (Ms 99732) that he worked for a silver spoon manufacturer, and here was corroboration! What is fascinating about this man is that we not only have his diaries and some correspondence, but we also have his magician’s paraphernalia. Walker was a puppeteer and magician in his free time, making him an unusual character study. We also went “aha!” when we discovered a reference to Prudence Crandall, the woman who ran a school for African American girls in Canterbury, in the account book of Stephen Coit, 1812-1835 (Ms Account Books).

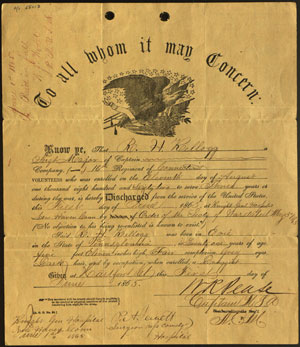

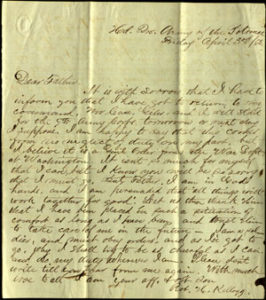

Another important part of our grant-funded cataloging is the active search for connections between archival material and museum collections. As an example, in the archives we have papers and diaries belonging to Robert Hale Kellogg (1844-1922), a Sergeant Major with the 16th Connecticut Volunteers in the Civil War. Kellogg enlisted from Wethersfield, Connecticut. He was an unmarried apothecary when he enlisted in the Union Army on August 11, 1862. He was mustered—in as a private on August 24, 1862, was promoted to sergeant in May of 1863, and promoted again to sergeant major on December 7, 1863. Kellogg was captured on April 20, 1864, at Plymouth, North Carolina. He was held at Andersonville prison, but was paroled in November 1864 and was discharged June 1, 1865. Kellogg wrote a book about his experiences in the war, entitled Life and death in rebel prisons: giving a complete history of the inhuman and barbarous treatment of our brave soldiers by rebel authorities, inflicting terrible suffering and frightful mortality, principally at Andersonville, Ga., and Florence, S.C., describing plans of escape, arrival of prisoners, with numerous and varied incidents and anecdotes of prison life. By Robert H. Kellogg … Prepared from his daily journal, which is available in our library. Some of his notes used in preparing the book are included in this collection. The diaries cover his time in the war, between 1862 and 1865. The letters were sent to his parents, Silas and Lucy Kellogg, of Sheffield, Massachusetts. Other Civil War—related items include his enlistment, promotion certificate, discharge, a New Testament Kellogg carried with him, and a prayer book. Also included are correspondence, writings, and photographs.

To complement the archival materials, in the museum is Kellogg’s forage cap, a gold locket with a fragment of the 16th Regiment’s flag, and an 1894 commemorative G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) medal. Think of the possibilities here: we could examine the role of religion among the soldiers by highlighting the New Testament and prayer book, and look for references to God and faith in his letters, his notes, and his published book. We also have a selection of fragments of regimental flags from the Revolution and the Civil War. Kellogg’s fragment would help us explore why the men took these souvenirs, and perhaps tell the story of the pride the soldiers felt in fighting for their country, or the bonds formed with fellow soldiers in the regiment.

As of March 1, 2010, we have cataloged 1200 collections, well beyond our expected 900. It has been an education for us, as archivists, to unlearn many years of common practice. However, I find that I apply MPLP to most if not all incoming collections now. Each collection, whether part of the grant or newly arrived, is assessed on an individual basis, and if items really need extra handling, we will put them in protective sleeves or acid-free folders.

We have used this project as a basis for future planning. NHPRC also has a grant program for detailed processing, where narrative guides are created and published on the web. As we cataloged the 900 records stipulated in the grant, and the additional ones we have examined, we noted which collections required more processing, which ones needed conservation, and which had documents with valuable autographs that should be scanned for researchers so that the originals could be removed for security. I cannot wait to get started on the detailed processing, which is the “bread and butter” of archival work and how I was trained. However, I think we have done an immense service to researchers by letting them know what we have, even if we’ve only offered them a teaser. And as more researchers use these collections, we will rely on their growing expertise to let us know more about the materials. Catalog records and even guides can change to reflect new information. We may come to the end of the grant period, but our work will never end!

Further reading

If you are interested in reading more about the controversial MPLP approach to archives, see Mark A. Greene and Dennis Meissner’s article, “More Product, Less Process: Pragmatically Revamping Traditional Processing Approaches to Deal with Late 20th-Century Collections,” in American Archivist 68:2 (Fall-Winter 2005), Ê208-63. More information about the NHPRC Archives—Basic Grants program is available at http://www.archives.gov/nhprc/announcement/basic.html. A manuscripts blog highlighting CHS discoveries can be followed at manuscripts.wordpress.com.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.4 (July, 2010).

Barbara Austen, Archivist at the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford, Connecticut, dove into the archives full time after earning Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in History and a Master’s in Library and Information Science. She worked at the Fairfield Historical Society and the Connecticut State Archives before settling at the Connecticut Historical Society, where she has been since 2004.