Star-spangled Sentiment

O you up there! O pennant! Out of reach — an idea only — yet furiously fought for, risking bloody death — loved by me! So loved! O you banner leading the day, with stars brought from the night! Valueless, object of eyes, over all and demanding all — O banner and pennant! . . . I see but you, O warlike pennant. O banner so broad with stripes, I sing you only, Flapping up there in the wind.

—Walt Whitman, Song of the Banner at Daybreak

I. O you up there! O pennant!

In 1861, the skies of New York were filled with red, white, and blue cloth, waving defiantly at enemies of the United States. The Confederate assault on Fort Sumter might have been bloodless, but it produced the same flag-draped mixture of anger, sorrow, and anxiety brought on by the nearly three thousand deaths on September 11, 2001. At the outset of the Civil War, as in the months following 9/11, America was ready to follow Walt Whitman and “see but you, O warlike pennant” and to “sing you only, / Flapping up there in the wind.”

Patriotic fervor of the spring of 1861 reached a high point on April 20, when the oversized Stars and Stripes, recently evacuated from Fort Sumter, arrived in Manhattan. During a “monster rally,” U.S. commander Robert Anderson carried this banner into Union Square and placed it in the sculpted hands of George Washington himself. A photographer captured the scene by positioning himself above both the crowd and the first president’s huge equestrian monument. In this blurry image, the throng looked upward, gazing towards an emblem that would soon be carried into war.

A few weeks after this spectacle, Henry Ward Beecher tried to make sense of the incessant Union flag waving. “Our Flag carries American ideas, American history, and American feelings,” he explained, which had “gathered and stored” the idea of liberty ever since the colonial period. If Beecher overstated the Stars and Stripes’ age, he still captured the main sources of its appeal. Weaving together abstract values, past events, and passionate emotions, the American flag had already become a nearly religious presence across the North. By the end of this war, it would generate an even more powerful aura, which would be perpetuated through America’s uniquely flag-centered patriotism.

In recent years, the American flag’s mystical power has never been far from sight. Pledges from schoolchildren, pregame renditions of the “Star Spangled Banner,” and never ending controversies over flag desecration all testify to Americans’ regard for patriotic cloth. During periods of crisis, Americans’ flag passions rise to their highest levels of intensity. The past year and a half has made this clear, whether one considers the flag-draped coffins of New York or the Pentagon or the thousands, if not millions, of banners hung from windows and porches in the fall of 2001. In this most recent resurgence of patriotism, flags with special associations have generated the most attention, just as they did in 1861. A flag pulled from the Ground Zero rubble missing twelve of its stars gained headlines by traveling to the World Series, to the Super Bowl, and, in its last and most controversial public appearance, to the opening ceremonies of the 2002 Winter Olympics. Another, emblazoned with comments written directly on its cloth by visitors to the World Trade Center site, went via navy ship to Afghanistan, where United States troops raised it over Kabul.

It is worth considering why Americans have invested their flags with such importance and how the United States has become more saturated with patriotic color than any other country in the world. The comparative intensity of American loyalties is less noteworthy than the country’s fixation on a single symbol, which has come to be associated with a remarkably wide range of emotions. Americans’ devotion to patriotic cloth has its taproot in the American Civil War, when the cult of the Stars and Stripes intensified just as it broadened its range of associations. During the war for the Union, the flag merged popular energies with government power, while sanctifying the country’s idealism with the shedding of blood. As in the Union Square pairing of flag and founder, the national banner in these years also threaded together present emergencies with the country’s imagined past.

America’s emotional attachment to flags attests the country’s penchant for patriotic spectacle. But flag culture had larger significance, especially in helping the country modify the European path to nationhood. What made the United States’ case special, if not wholly exceptional, was that its flag cult helped to build collective authority on willing sacrifice rather than on sheer national strength. It was a combination of blood and cloth, rather than of blood and iron, that accounted for the star-spangled sentiment of the 1860s. This mixture gained potency as it was passed down to later generations, who would continue to use the flag both as a sign of inspiration and as an all-too-effective instrument against dissent.

II. Out of reach — an idea only . . .

Today’s patriots tell a very particular story about the history of the American flag. In this story, Flag Day marks the anniversary of the banner’s “birth,” with Betsy Ross its mother. The flag’s thirteen stripes document the initial size of the Union, just as its fifty stars tell of the nation’s growth. The flag’s story is always accompanied by rousing music and streaming banners, as the flag not only leads Americans through war but also presides over defining experiences like immigrants’ arrival at Ellis Island, African-Americans’ quest for voting rights, and Neil Armstrong’s landing on the moon. As omnipresent as Woody Allen’s Zelig, the Stars and Stripes seems to have missed few truly important events in American history.

It took considerable energy to create this tapestry of flag images and icons. In many cases, patriots had to retrospectively drape the past with stars and stripes, especially when portraying the flag’s earliest years. The Founders’ own comparative neglect of their new national symbols required later generations to fabricate—out of whole cloth, one might say—a series of legends that could project flag passions back in time. The best-known case was the Betsy Ross story, which was first presented to the American public in the 1870s. Other famous patriotic images, such as Emmanuel Leutze’s 1855 Washington Crossing the Delaware or Archibald Williard’s slightly later The Spirit of ’76, were part of this same process.

Specialists on American flag culture agree that the earliest roots of star-spangled sentiment lay not in the Revolution but in the country’s second war with England. The war’s most notable creation was Francis Scott Key’s “Star Spangled Banner” which would give the flag a name and the country a national anthem. Less lasting, though no less important to the 1810s, was Joseph Rodman Drake’s poem, “The American Flag,” which focused not on a particular scene, but on this symbol’s mystical origin, imagining the flag’s first heavenly appearance:

When Freedom from her mountain height Unfurled her standard to the air, She tore the azure robe of night And set the stars of glory there. She mingled with its gorgeous dyes The milky baldrick of the skies, And striped its pure celestial white With streakings of the morning light.

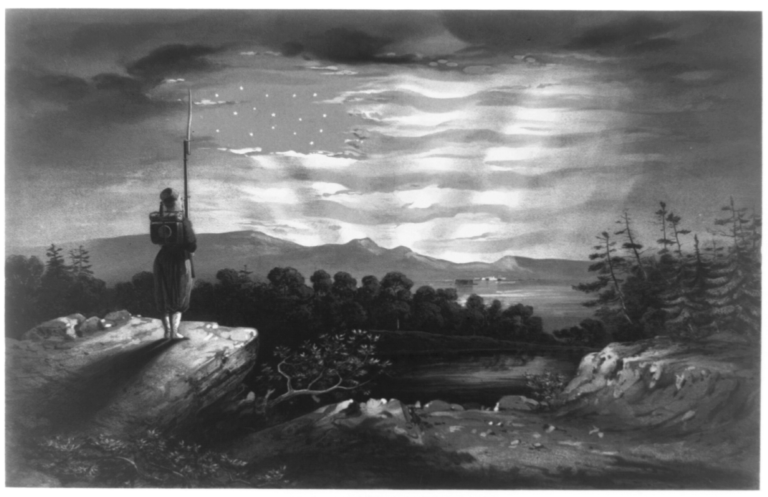

Drake’s association of the flag with the “Freedom” of heavenly stars lasted through the secession crisis, when his first stanza was placed directly beneath the 1861 lithograph Our Heaven Born Banner. The soldier in this picture, and all the viewers who were implicitly asked to follow his gaze, confronted a mystical image that was meant to change the way they saw the colored cloth suddenly waving in nearly every public place.

At the same time that Drake’s poem was accompanying new images, Key’s more famous tribute from the war of 1812 was generating criticism. Richard Grant White led a committee in 1861 to choose a more appropriate national song than the “Star Spangled Banner,” which he and other genteel critics associated with spread-eagle expansionism and anti-immigrant nativism. “Who cannot but wish that the spangles could be taken out,” White asked, “and a good, honest flag be substituted for the banner!” What the country needed, he believed, was a set of patriotic tunes and rituals that were less specific in their associations and less warlike in their imagery and tone. In 1861, Henry Ward Beecher echoed this view in associating the flag not with armies but with the noble ideas associated with its “bright morning stars of God” and “beams of morning light.”

The “Star Spangled Banner” survived the Civil War, of course, though it would be joined by wartime flag music that, while just as bellicose, would lend a new sense of purpose to the violence associated with flags. The only blood of Francis Scott Key’s anthem was that of invading soldiers and slaves, which, as Key explains in his largely forgotten third stanza, “wiped out their foul footstep’s pollution.” Drake had similarly emphasized how the American flag could blot out violence, as he urged the banner to “ward away the battle-stroke” and to turn soldiers’ eyes upward so that they might look away from “the life-blood, warm and wet” that had “dimmed the glistening bayonet.” In contrast to such lyrical gestures, Civil War poets like Julia Ward Howe focused far less on the triumph of killing the enemy than on honoring patriotic martrydom. By the end of the war, the patriotic ideal of looking upwards towards higher ideals would be joined to an even more solemn task of gazing downwards on fallen bodies.

III. [Y]et furiously fought for, risking bloody death —

Civil War bloodshed brought the American flag down to earth and made the cloth repository of national ideas into a powerful means of commemorating sacrifice. Caroline Marvin and David Ingle have recently explored this aspect of American flag culture from a sociological perspective, drawing attention to how death has endowed the Stars and Stripes with its sacred qualities. Their analysis helps to explain why veterans and their families have regularly taken the lead in protecting the sanctity of American symbols.

The roots of America’s blood-soaked flag cult lay in the ancient martial ideal of sacrificing one’s body for a banner. There was nothing distinctively American about soldiers’ willingness to be “sabred into crow’s meat” for “a piece of glazed cotton,” as Thomas Carlyle had put it in 1831. Indeed, for Victorian observers, this death-defying martial heroism was distinct from national loyalty and perhaps even in tension with it. John Stuart Mill considered that single-minded “devotion to the flag” was evidence that a country lacked other cohesive and inspiring ideas. With the Austrian Empire in mind, he denounced armies held together only by the colors of battle as “executioners of human happiness” whose “only idea, if they have any, of public duty is obedience to orders.”

While American soldiers nurtured a martial flag cult within their own ranks before the Civil War, the larger public tended to associate the national flag primarily with the country’s ideas rather than its armies. Significantly, the first attempt to bloody the Stars and Stripes came not from those hoping to glorify the flag but from abolitionists who sought to discredit American hypocrisy. The poet Thomas Campbell began the conversation in 1838, calling out from England:

United States, your banner wears Two emblems–one of fame; Alas! the other that it bears Reminds us of your shame. Your banner’s constellation types White freedom with its stars, But what’s the meaning of the stripes? They mean your negroes’ scars.

Garrisonian abolitionists picked up this image and made the sinister associations of the red, white, and blue part of their campaign against slavery. Their shift of attention from the flag’s heavenly stars of divine hope to its bloody stripes of guilt pricked at national pieties as effectively as their public burnings of the Constitution.

The flag would be changed more radically by the torrent of bloodshed that ended slavery’s massive violence. Through this crucible, white Americans imagined far more intensely than ever before how their country’s commitment to liberty rested on a set of violent underpinnings. Abraham Lincoln lent a vocabulary to this “new birth of freedom” which involved both a revolutionary dedication to principle and martyred soldiers’ dedication to a republic that they had valued above their own lives. In language tinged with the Christian hope of redemption through death, it was soldiers’ blood that regenerated the republic and allowed it to live up its own founding propositions.

An ever expanding cult of the American flag was a key part of imagining this secular counterpart of the Christian passion. During the spectacle of combat, banners inspired soldiers to acts of death-accepting patriotism, which were made a national ideal through poetry, song, and images. Common soldiers, and especially the mythically brave flag bearers, came to occupy a central place in the popular imagination. As casualties mounted, flags commemorated the heroism of those who had carried them into battle. Banners brought back from the front torn and tattered, covered with smoke, and riddled with bullets were cherished as sacred relics. A mystical aura even emanated from enemy banners, since it was only through acts of courage that these had become captured trophies.

African Americans best appreciated how Civil War bloodshed transformed the United States flag from a symbol of betrayed idealism to an emblem of liberation. Shortly after Confederate surrender, the Reverend E. J. Adams of Charleston drew the attention of former slaves to “the bloody crimson stripes” on the American flag to make a larger point. “Once emblematic of the bloody furrows ploughed upon the quivering flesh of four million of slaves,” he explained, these stripes became thereafter “emblematic of the bloody sacrifice offered upon the altars of American liberty.”

IV. So loved! O you banner leading the day, with stars brought from the night . . .

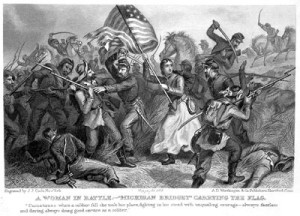

If the wartime Stars and Stripes began to resemble earlier martial flag cults, it never lost its wider associations with the national promise of liberty. Sacrificing on behalf of popular government and emancipation was, from the perspective of most Unionists, every bit as important as their own valor under arms. Just as importantly, the involvement of women in flag culture imbued the flag with other new meanings, creating a distinctly domestic allure evident in a skirt-clad “Michigan Bridget’s” supposed role as flag bearer in a contemporary illustration.

Women’s involvement in the war involved a wide range of flag activities, most of which were far less martial than those of Michigan Bridget. Female patriotism was staged with the greatest fanfare at flag presentation ceremonies, when local women unveiled cloth gifts of their own construction and, in many cases, of their own design. One writer noted that it was through such events that the “reverence for the flag amounting almost to worship” acquired a “human face or word.” Elaborately staged ceremonies were meant to give soldiers a set of memories that might sustain them under more trying circumstances. Marching off to war with a gift from home helped them to personalize devotion to country, cause, and their own sense of soldierly honor.

In an array of subsequent efforts, Union women took control of the flag’s sentimental meanings, which would coexist with the same symbol’s evocation of men’s willing sacrifice. They celebrated it in a flood of flag-related poetry in the daily press and in popular magazines. They made it a prominent part of the visual landscape by displaying it from windows in both cities and towns. John Greenleaf Whittier’s Barbara Frietchie was even bold enough to shame Stonewall Jackson into respecting the American flag his troops attempted to shoot from the second story of her home in western Maryland. As Whittier recounted, in a refrain that echoed into the twentieth century:

Quick, as it fell, from the broken staff Dame Barbara snatched the silken scarf; She leaned far out on the window-sill, And shook it forth with a royal will. “Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country’s flag,” she said.

The legendary daring of Michigan Bridget and Barbara Freitchie were matched by more secretive, if far less celebrated, efforts of loyal women in the deeper South to harbor American flags behind enemy lines. At the conclusion of the war, such contraband cloth was pulled out of hiding to prove that faith in the Union cause had never waned. The Vermont native Cyrena Stone waved her miniature Stars and Stripes when Sherman’s troops arrived in Atlanta. She had kept this sacred memento throughout the war, hiding it in jars of fruit and in her sugar container when not sharing it with her larger circle of Atlanta Unionists. Press reports also told of how an unnamed black woman in 1865 electrified a Virginia crowd by producing a banner that she too had hidden, at the risk of far greater reprisals, from white Confederates fighting for their freedom to keep her in slavery.

Women’s involvement in the Civil War cult of the Stars and Stripes broadened the range of daring war experiences while it also tinged this symbol with a distinctly domestic hue. Brought within Union households, American flags became part of the civics lessons that mothers had incorporated into the patriotic education of American children. A contemporary writer noted the ultimate effects of making the Stars and Stripes into a “household idol in every Northern home.” Children exposed to such shrines at home were “imbibing a strange love for [the flag] that will tell upon their devotion to country in their future history.” In a telling prediction, he also noted that a symbol “planted in the hearts of men” would be “readily received by them calling forth their love and veneration” thereafter.

After the war, women took on added flag responsibilities in grieving dead soldiers. Patriotic color was a centerpiece of commemorative activities that began in 1865, when black Unionists decorated the graves at the Charleston racetrack. In the tradition of Memorial Days that followed, flags that had been soaked with blood became imaginatively doused with tears. Female groups took the lead in the ceremonial bereavement that shaped how both Unionists and the Confederate would honor their dead. Such rituals depended for their power on the Victorian association of heaven with the virtues of home. But it also perpetuated what would become an instinctive reliance on flags to give solace during times of national tragedy.

Flags’ ever expanding uses in the postbellum period coincided with the growth of a United States’ bunting industry. Patriotic cloth entered nearly every aspect of Americans’ life in these years, with female consumers leading the way. Love for colors accordingly came to depend as much on the flag’s ubiquity as its special associations. This trend continued, despite efforts to protect patriotism from the effects of commercialization. Some feared that the cult of the flag might be diluted if the symbol was not harbored away except in the most solemn occasions. They need not have worried. In the first years of the twenty-first century, Americans have continued to treat the cloth form of flags with nearly religious respect, even while they have been busy pasting its image to every conceivable form of T-shirt, bumper sticker, or household decoration.

V. Valueless, object of eyes, over all and demanding all . . .

The Stars and Stripes emerged from the Civil War with a wider range of associations than any other national symbol. A vibrant flag culture honored the country’s ideals, its history, its fallen men, and its patriotic women. The war for the Union also bolstered the flag’s status as a symbol of supreme national authority. From the secession crisis through the final collapse of the Confederacy, flag-waving Unionists called on government power to suppress an internal threat. When Confederates surrendered, the same flag presided over the loyalty oaths that brought rebels back into a national community of the red, white, and blue.

The dynamics of rebellion, coercion, and sentimental reunion were as long-lasting as any aspect of Civil War flag culture. The Confederate threat against the United States passed quickly enough, aided by Northern whites’ fateful preference for national harmony over racial justice. But by the 1890s, the flag was taken up against the perceived threats posed by immigrants, political radicals, and other suspected dissidents. Civil War veterans played a key role in bringing the flag into the public schools and in popularizing new patriotic rituals such as Francis Bellamy’s Pledge of Allegiance. This period saw considerable innovation in matters of organization and codification, which would become a permanent part of how Americans subsequently treated their banners. Yet despite such innovations, the prevailing blend of martial drill, sentimental tributes, and historical tableaux of the 1890s clearly echoed trends first established thirty years earlier.

Francis Bellamy marveled during this late-century patriotic revival that the Stars and Stripes had “as great a potency to Americanize the alien child as it has to lead regiments to death.” Here Bellamy identified the crucial element of voluntarism enshrined in the country’s cult of the flag. By focusing on the willing sacrifices of soldiers, banners had both glorified and obscured wartime violence. The flag-draped repentance of former Confederates rested on a double evasion, turning attention away from the force used to suppress their rebellion and from the brutal racial order that accompanied the growth of sectional amity. Flag rituals meant to “Americanize the alien child” similarly replaced the coercive elements of nationality with a simpler, happier story. In each of these instances, Americans conceived individuals free from outside pressure succumbing to the flag’s inevitable tug upon their heart.

Idealizing patriotic consent has never meant an unwillingness to use coercion, of course. Blood was a vital part of America’s path to nationhood, even if the country’s love of cloth became a national ideal in the way that its blunt use of iron would not. When the country has come under attack, star-spangled sentiment may have brought solace and comfort. But it also has fanned the flames of war. The intimate relationship between patriotic pride, the thirst for vengeance, and the squelching of dissent, has been evident enough in the year and a half since September 11, 2001. On a practically daily basis, we are reminded of that imaginative color line that equates outward display with inner conviction.

Since the Civil War, Americans’ flag patriotism has rested on the uneasy coexistence of freedom and sacrifice, sentimental love, and supreme authority. Yet if the 1860s established these themes, it neither fixed their meaning nor established their relationship to one another. This has been clear in the long-running dispute over the flag’s sanctity that has roiled local authorities, the courts, and politicians for much of the twentieth century. Such recurring conflicts have raised basic questions about state-sponsored patriotism and the limits of dissent. In these, banners have both roused emotions and, ironically enough, marked the boundaries of government power by helping to establish official protection for even the most controversial forms of symbolic speech.

The latest flag flap has concerned the Pledge of Allegiance, and specifically the phrase “under God” that was added to Bellamy’s composition during the Cold War. This episode, which was as fierce as it was short-lived, tended to obscure the true nature of the flag cult’s religiosity. American patriots, both now as in the past, have regularly invoked the Almighty. Even Francis Scott Key ended his anthem with the rousing charge, “In God is our Trust” (words every bit as forgotten as the rest of his second, third, and fourth stanzas). Yet popular reverie for the flag has depended, in the end, on a more secular, if no less mystical, communion between the living and the dead.

What makes the American flag a religious object is evident less in the words of pledges and the lyrics of anthems than in the national rituals that frame such professions. These moments’ half-conscious gestures dramatize a transaction that temporarily makes a gathering of strangers into a community of sentiment. The red, white, and blue cloth that centers attention receives the praise of patriotic voices and the collective gaze of patriotic eyes. Yet in raising their hands to their chests, participants in these ceremonies acknowledge an even deeper set of commitments involved in America’s flag cult. As has been true at least since the 1860s, a flag-waving nation has expected something more than the loyalty of their citizens’ bodies and the devotion of their minds. It has also sought, with a success that earlier generations could scarcely have imagined, the love of their citizens’ hearts.

Further Reading: George Henry Preble’s voluminous The History of the Flag of the United States (Boston, 1880) has long been the starting point for understanding America’s nineteenth-century flag cult. His explicitly patriotic approach should be read along with Scot M. Guenter’s more analytical The American Flag, 1777-1924: Cultural Shifts from Creation to Codification (Rutherford, N.J., 1990), and with the more theoretical approaches of Caroline Marvin and David W. Ingle, Blood Sacrifice and the Nation: Totem Rituals and the American Flag (New York, 1999) and of Albert Boime The Unveiling of National Icons: A Plea for Iconoclasm in a Nationalist Era (New York, 1998). The following (which are listed in order of the periods they survey) provide historical context for the flag’s place in American patriotic expression: Charles Royster, “A Nation Forged in Blood,” in Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert, eds., Arms and Independence: The Military Character of the American Revolution (Charlottesville, 1984); Mark Wahlgreen Summers, “‘Freedom and Law Must Die Ere They Sever’: The North,” in Gabor S. Borrit, ed., Why the Civil War Came (New York, 1996); Mark E. Neely, Jr. & Harold Holzer, The Union Image: Popular Prints of the Civil War North (Chapel Hill, 2000); Robert E. Bonner, Colors and Blood: Flag Passions of the Confederate South (Princeton, 2002); Alice Fahs, The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861-1865 (Chapel Hill, 2001); Gaines Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South (New York, 1987); David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); Cecilia O’Leary, To Die For: The Paradox of American Patriotism (Princeton, 1999); Stuart McConnell, “Reading the Flag: A Consideration of the Patriotic Cults of the 1890s,” in John Bodnar, ed., Bonds of Affection: Americans Define their Patriotism (Princeton, 1996).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.2 (January, 2003).

Robert E. Bonner teaches American history at Michigan State University. He is the author of Colors and Blood: Flag Passions of the Confederate South (Princeton, 2002).