Storm of Blows

Follow the tabloid pages of the National Police Gazette of the 1890s as they move from right to left across the screen of the microfilm reader until your neck is sore, past the vaudeville pinups with their substantial thighs (“girls in tights!”), past the tales of murder, hangings, deadly stampedes, train wrecks, floods, whippings, and factory yard brawls; women acting out, smoking cigars, or dressing as men; past the dudes, dandies, slims, sports, and cranks. Before the classified ads for marked cards, restored manhood, rubber goods, cabinet photos of couples In the Act, counterfeit greenbacks, loaded dice, photographs of fighting cocks (choose between Billy of Missouri, Big Jim, Old Katie, or Billy of California), opium habit cures, remedies for sexual weakness and shrunken organs (“O Weak Man Do Not Despair!”) there is a relatively new and novel feature of journalism: the sports pages. And though the tabloid would cover baseball, cycling, pedestrians, even strong men (and women) contests, even yachting, and would publish challenges from checkers players and glass eaters and pie eaters (“Dear Sir—I Joseph McGivney, having defeated all pie-eaters in Harlem, am looking for greater fame . . .”) and solo guitar players, sports truly meant one thing to the Police Gazette: the world of boxing.

It was boxing, and also Fistiana, and Pugilistica. The fights were bouts, but also battles, mills, and set-tos. A pugilist might be knocked out or “put to sleep.” They all had nicknames. The Nonpareil, the Corkscrew Kid, Little Chocolate, many Youngs and many Kids, and, of course, the Boston Strong Boy.

The country of Fistiana was large then: it was bounded by England and South Africa and Australia, with the United States as its center. Depending on varying degrees of legality and local support, the American scene was continually shifting as the decade progressed, and the fighters were on the move, riding the rails to box, or second, or witness bouts. But this scattered fight scene once had a hub, the first true center of the vortex: the city of New Orleans. To travel to this stretch of boxing history is to go south, and catch a glimpse of the sport’s modern version as it struggles to emerge. Here in New Orleans, bourgeois Victorian men preoccupied with virtue, order, and “scientific” sport will openly adopt and attempt to legitimize an unforgiving, lower-class pastime. They will briefly succeed in shedding pugilism’s seamy stigma, but the move from saloon backroom to refined athletic club to consumer spectacle will prove to be risky and tumultuous.

I. The Fistic Carnival

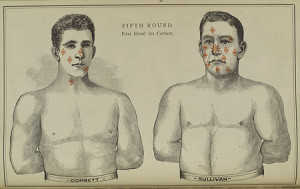

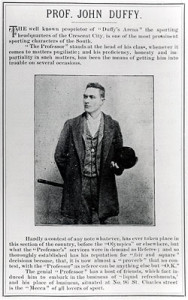

Start at the top: New Orleans, in its palmiest boxing days, circa 1892. It is the last night of the Fistic Carnival, three nights of championship bouts in stagnant early September, culminating in the Sullivan-Corbett heavyweight title fight. The host Olympic Club stands like a four-story ship with banners strung from gables, filling a long bywater block, bounded by Chartres and Royal, Montegut and Clouet. Every window is lit. Streetcars arrive constantly from Canal—the Levee and Barrack cars—and the streets around the club are clogged with hacks. There is the threat of rain, as always. Inside, in the rare quiet moments before the fight, is the clatter of telegraphs, and the sixty electric lights boasted of are spitting noise. When the referee, “Professor” John Duffy, steps into the ring, he receives a “deafening” ovation; he receives an ovation, in fact, before every bout. Duffy is presented with a silver punch bowl, in appreciation of his skill and rectitude. “Gentlemen, I am completely knocked out, or I would say something,” he replies.

The Fistic Carnival has driven the upcoming presidential election and Lizzie Borden and cholera from the front pages, and not only in the city of New Orleans. Instead this is news: trains have been arriving all week, specially booked Pullman cars, from as far away as Buffalo. The Illinois Central has advertised its special “Green Room” excursion from Chicago, a “solid vestibule train of sleepers” including “a special commissary car . . . serving lunches, wet goods, and cigars.” Twenty-five dollars roundtrip. The papers are full of minutiae. So this is also news: referee Duffy’s cousin Arthur has come to town. The gloves, ordered from New York, weigh five ounces each, and will be tan.

This night, September 7, 1892, is the pinnacle of the New Orleans fight scene, a scene that epitomized the struggles and the extremes of the sport during its four-and-a-half year reign. It is also a historic night, for the champion is dethroned. John L. Sullivan has reigned for ten years, but the younger James Corbett emerges victorious after twenty-one rounds. When the Boston Strong Boy goes down, referee Duffy is forced to pantomime the count, and the declaration of victory, amid the uproar. Corbett later recalled that belts, coats, hats, and canes, and flowers from buttonholes—the accoutrements of gentlemen—are all flung his way. A spectator wrote that the sound is louder than “a whole herd of Kansas cyclones.” A “hoarse roar,” is what another witness remembered. Despite the tumult, Duffy is able to quiet the crowd, and Sullivan staggers to the ropes and says:

Gentlemen, all I have got to say is this. I stayed once too long. I met a younger man, who proved too good for me, and I am done.

Or something like that.

Fights were reported in what John Kouwenhoven called the “syntax of momentum,” a peculiarly American and dynamic style of writing he found in an early transcontinental railroad guide. The headings will not slow you down; they are part of the rush. As the Sullivan-Corbett bout reels to its conclusion, here is how the New Orleans Times-Democrat titles its rounds:

SULLIVAN WAS SO THOROUGHLY SURPRISED CORBETT NOW BEGAN TO FORCE THE PACE CORBETT WAS THE AGGRESSOR HE FOUGHT WILDLY SULLIVAN STAGGERED BACK SULLIVAN STAGGERED BACK STORM OF BLOWS.

This is boxing as relentless progress, as the myth of late-nineteenth-century American life.

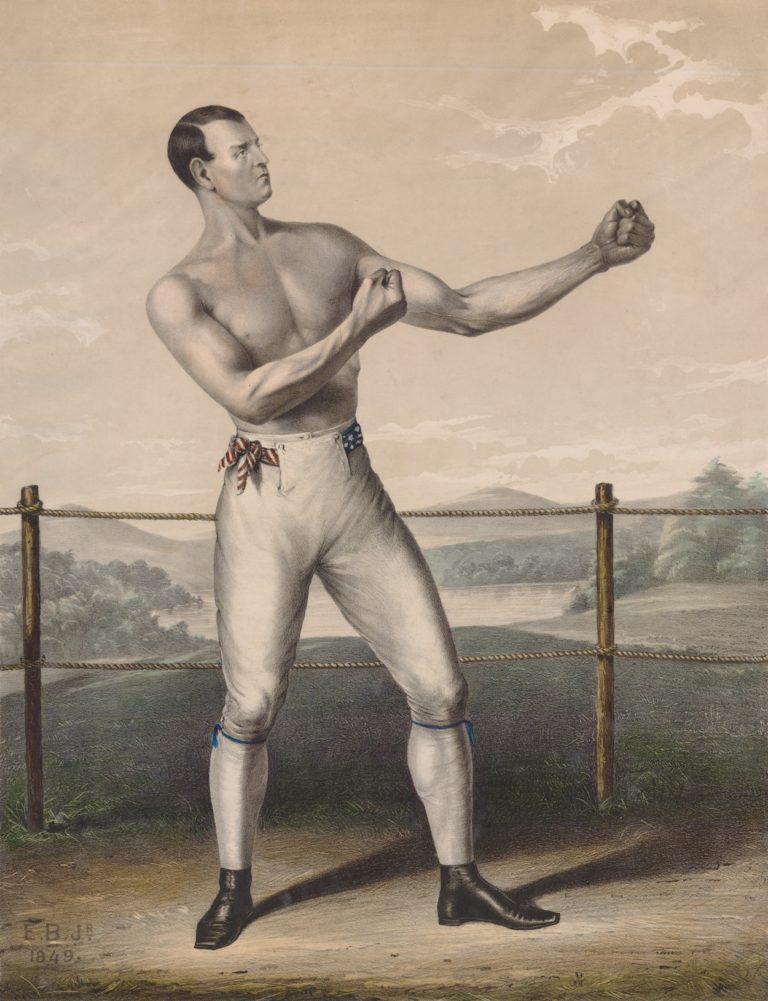

But no matter how progressive, or how much it seemed to reflect a vibrant spirit of competition, of Darwinian triumph and bootstrap optimism, boxing still suffered from an image problem. Though middle- and upper-class Victorian men took up the sport with enthusiasm in the era of rugged “manliness,” as both spectators and recreational participants, many still considered fistiana a “bloody and brutal” world. New Orleans, long a sporting city of “moral laxity” and leisure that worshipped the “gospel of play” (even on Sundays), was an ideal setting for boxing to thrive illegally in the years after the Civil War. The city would ultimately become the first in the country to attempt to truly legitimize pugilism by sanctioning it in 1890. Boxing’s proponents wanted more than mere legal acceptance, however; they sought respect, and hoped to sell the sport to civic leaders and to its myriad of local opponents (including the clergy and the Louisiana attorney general), and to rise above the sordid, illicit image that it evoked. Here in New Orleans is the knotty shift in boxing’s history from bareknuckled fighting (the London Prize Rules) to gloved fists (the Marquis of Queensberry Rules); from illegal rings furtively pitched by pine trees to reserved seating under electric lights in elegant athletic clubs.

It was these athletic clubs—a recent, nationwide phenomenon—that gave boxing its new veneer of credibility, and the Fistic Carnival’s Olympic Club epitomized the trend. “The Olympic Club is creating a respect for manly sports, a respect for honest, unafraid muscle,” the carnival program declared. Its officers moved in the city’s commercial elite: lumber, coal, cotton, real estate, insurance, “levee interests,” “capitalists.” President Charles Noel, for example, was a partner in a sawmill and sat on the city council, serving as committee chairman for streets and landings. The Olympic’s “renaissance style” clubhouse (costing $30,000) included a library and reading rooms, decorated with objects of art. Finances seemed unlimited—more improvements were planned, and purses were high. The club put $25,000 (the equivalent of nearly $500,000 today) toward the total $45,000 purse in Sullivan vs. Corbett.

New Orleans would support pugilism so long as its participants adhered to a number of conditions: professional fights must be held in chartered athletic clubs and conducted under police watch, $50 from each match goes to charity, there is no Sunday fighting, and no drinking among the spectators. And, of course, all fighters must now wear gloves. The image desired was one of order (a recurring word) and uprightness, of hatted men with canes calmly witnessing a “scientific” fight unfold. Boxing taught “manly, honest, straight up and down lessons on the right side of patriotism, of health, of decency and morality,” the Fistic Carnival program proclaimed.

Even the carnival’s heavyweight title fighters fit boxing’s redefinition scheme. The defeated John L. Sullivan, the bareknuckled champion of the sport’s illegal days, is a drunk; he has been arrested, he is a slugger of unlawful and hidden fields. James Corbett, the victor, is a bank clerk who appeals to the ladies with his pompadour, a “scientific” fighter, and a “gentleman.” “James J. Corbett lifted boxing out of the barroom slough,” Nat Fleischer later claimed. Corbett’s triumph in New Orleans seemed to seal the lofty claims of boxing’s proponents, and reflected the sport’s grand ascent.

To remain legal, though, boxing would need to sustain the support and esteem of the “better classes of people” who were patronizing the fights—the “doctors, lawyers, state and municipal officials and representative prominent business men, bankers and even public educators” who packed the stands at the Fistic Carnival. This precarious situation was exemplified by the attitude of the Daily Picayune, one of the city’s leading newspapers. Though its pre-carnival coverage enthusiastically filled nearly 20 percent of its Sunday content, an editorial that ran the next day made it clear the paper’s support of boxing was highly qualified. “The Picayune is by no means an advocate of prize fighting,” it began. But since the upcoming fights were “the most prolific and absorbing subject of conversation in this country,” no newspaper could “ignore their importance.” Only if the sport could maintain a sense of order and decorum, the editorial implied, would it retain the patronage of “men of culture, wealth and high social standing.”

New Orleans, perhaps, had something at stake as well. Successful boxing events like the carnival brought hoards of visitors, money, and much favorable national publicity to a city known to many as a haven of disease and debauchery. Strangely enough, in 1892, it appeared a sport long considered “bloody and brutal” would become respectable in the so-called “city of sin.”

II. Duffy’s Arena

The ubiquitous Professor John Duffy, the referee of the Fistic Carnival, becomes the hero of pugilism’s palatable new image. Duffy, who participated in every capacity within the New Orleans boxing world—as a fighter, instructor, saloon and arena keeper, matchmaker, and money holder—reached his fame as a leading referee, known for his unfailing honesty and skill; Duffy, in all reportage about him, is the pure embodiment of probity. An entire page of the Fistic Carnival program was devoted to his character, to his “reputation for ‘fair and square’ decisions.” The pro-boxing press, particularly the Police Gazette, promoted the figure of the “universally respected,” upright referee (others included Bat Masterson and “Honest John” Kelly) in its effort to sell the sport. Duffy’s sketched likeness appeared often, representing the new order of things.

He was the youngest son of Irish parents. An early fighting gig found Duffy as a warm-up act for John L. Sullivan’s touring vaudeville routine in 1884. At the age of twenty, at the St. Charles Theater, he sparred three rounds with Peter Burns: “toward the last, they warmed to their work,” the Daily Picayune reported, “and pounded each other’s faces until the gallery gods howled with joy.” Duffy continued to fight and spar (once against a fighter known as the Big Gas Man), then became an instructor of pugilism for the Southern Athletic Club, on the corner of Prytania and Washington. One of the new breed of athletic clubs, the Southern, like the Olympic, catered to an upscale crowd, boasting of its decorum and equipment, all dumbbells and horizontal bars and “lofty tumbling,” and athletic exhibitions for the ladies.

Duffy, “popular with the better element” and possessing “a host of friends,” soon opened his own boxing establishment: Duffy’s Arena, at 96 St. Charles Street. As the venture was not a chartered athletic club, fights could only be held there as exhibitions, with no prize money involved. The arena was also a saloon. Duffy often tended bar there, and boxing devotees from around the country, in town for the Fistic Carnival and other big events, congregated at his arena, “the ‘Mecca’ of all lovers of sport.”

In February 1893, six months after the carnival, Duffy arranged a routine, amateur glove contest. George Goodrich (a.k.a. Ed. Williams, as said his tattoo) was a mulatto steamboatman from Tennessee who purportedly frequented the Franklin Street dives. This was his first public ring fight; he had sparred before. Duffy matched him with his protégé, Joe Green, a bricklayer. The Daily Picayune would later describe the room where the fight was held as dark and dirty and little and close and bad smelling. Though both white and black spectators were allowed to view the matches they were admitted separately, and black patrons were relegated to the “dressing room,” the “unfinished space behind the stage, which had been separated from the stage by a flat of canvas, upon which had been painted rude pictures of Sullivan and Corbett,” through which a hole had been torn for viewing the fights. The Master of Ceremonies was George Queen (née McQuinn), the brother of a minstrel. A quartet’s singing began the night.

At some point in the second round, George Goodrich slipped on a patch of water (though the New York World reported it to be blood) while struggling to avoid a blow, fell, and broke his neck. No one yet realized that he was dead, though the rumors that he might be caused many patrons to quickly leave. Some of the men carried him to the dressing room and laid him on a pile of rags. Duffy was summoned, and he thought the man was fine and said so, adding that he would come around. “A crowd of bewildered and half frightened negroes and white men and boys crowded about the body of the fighter, and simply gazed at the prostrate man . . .” Then they tried to revive him. An ambulance arrived, the attendants held a candle over the body and declared the boxer dead while wax dripped onto his face.

“The grim reaper had played the part of time keeper and had counted the pugilist out,” the Times-Democrat melodramatically concluded.

SLIPPERY FOR MEN IN BOXING. HIS LEGS PARTED WIDELY, AN INERT PIECE OF HUMANITY. ENTERTAINMENT WAS RESUMED.

John Duffy, Joe Green, five accessories, and seven witnesses were booked at the First Precinct police station at 1:15 a.m. According to the record of arrests for the New Orleans Police Department, written in a fat scrawl and found at the city archives, Joe Green resided at 125 1/2 Perdido St., was colored, aged twenty, a slater, was single, and could read. He was charged with the murder of one Geo. Williams or Goodrich and remanded into custody without bail. The five additional accessories, whose occupations included laborer, porter, electrician, slater, and none, and the seven witnesses (all colored, ages fifteen to twenty-five) were held on a $250 bond each.

All pled not guilty at the arraignment. The Times-Democrat reported that when the Professor appeared before the judge, “his lips quivered visibly, and his cheeks assumed a fiery color foreign to them for many years. The hideous word ‘murderer’ was too much for John Duffy’s equanimity.” But the death was ruled an accident and all involved were acquitted of their charges in a well-attended hearing on February 8. “The prisoners were allowed to go and left the courtroom in cheerful spirits.” The dead pugilist, of whom “nothing was known” except that “he came from Nashville, and possessed a good voice,” was buried in potter’s field when no family came down from Tennessee to claim him.

Although Goodrich’s fatal bout was widely reported in New Orleans, the death of an unknown, black pugilist did not touch off any public clamor against boxing. Still, Duffy’s good name had been tainted, and the reportedly sordid conditions of his arena exposed. Complaints raised against his establishment by his landlady, Mrs. Bidwell, were divulged by the newspapers, complaints that included “exhibitions of his kids and other small boys.” Whether these were boxing exhibitions is not altogether clear; Duffy told his landlady that “it was an attraction by which he was enabled to sell a few drinks.” In addition, Mrs. Bidwell objected to the tobacco smoke and the noise and the “class of people attracted to the place.” Duffy survived all of this negative publicity, though he eventually moved his saloon, with his reputation more or less intact. He was, after all, acquitted.

III. The Death of Andy Bowen

The former lightweight champion of the South, Andy Bowen, was a local boxer who had worked as a blacksmith, and in cotton yards; he sparred on the levee in his early days, in between handling bananas; he worked the fruiters to Honduras. He was the unofficial champion of Annunciation Square. A “suspected mulatto,” in historian Jeffrey Sammons’s words, Bowen passed for white, was said to be of Irish-Spanish extraction, and purportedly denied all charges of colored blood, a denial that was accepted by the boxing community. To fight or witness bouts in the sanctioned, upper-class athletic clubs of New Orleans, which usually adhered to segregation practices soon to be institutionalized, one would have to be white. Reading the coverage of the local fight scene, it also becomes clear that the consummate boxer is implicitly Caucasian—note, for example, a description of heavyweight champion James Corbett: “CORBETT, TALL, BROAD-SHOULDERED and whiter in the pale rays of the electric light than a statue of ivory, looked an ideal athlete.”

Indeed, New Orleans’ athletic clubs became exclusively white after George “Little Chocolate” Dixon’s victory over the white boxer Jack Skelly for the bantamweight title, on the second night of the 1892 Fistic Carnival. This was the only night the host Olympic Club allowed black spectators, setting aside seven hundred seats in the upper gallery. Reaction to this interracial bout, and Dixon’s victory, made news. “The colored people on the levees are so triumphant over the victory of the negro (Dixon) last night that they are loudly proclaiming the superiority of their race, to the great scandal of the whites, who declare that they should not be encouraged to entertain even feelings of equality, much less of superiority,” the New York Herald opined. “They will become brutally insolent, and frequent and fatal collisions will be inevitable,” the Daily States (a local paper founded by a zealous Confederate major) editorialized. But hints of racial unrest are few in the coverage of the carnival and its aftermath; they do not conform to boxing’s claims to orderliness, and are generally missing from news accounts. Nevertheless, no black boxers would fight at the Olympic Club after that night.

Andy Bowen was a fixture of the New Orleans fight scene since its inception, and John Duffy often served as his referee. On December 14, 1894, Bowen lost an eighteen-round bout at the Auditorium Athletic Club to Kid Lavigne, the “Saginaw Kid.” Duffy, once again the referee, would later say that Bowen was not himself before his match, that he did not pay close attention to the usual details, and his enthusiasm was uncharacteristically low. The fight itself was increasingly one sided. In the first round, “Bowen’s left found a way to the nose, but failed to create much damage,” a harbinger of his weak showing; later “when he began working his arms like windmills his friends knew that he was gone.” In the last rounds of the fight “Lavigne did almost as he pleased with Bowen, though the latter would rally occasionally and land a rib-roaster. He had a habit of grunting pretty loud during the latter part of the fight, each time Lavigne landed a telling blow in the stomach, which he did pretty often, and the crowd laughed, which of course rattled him all the more.” In the eighteenth round, Bowen “staggered around like a drunken man,” clinched continually to save himself, and tried to avoid Lavigne’s blows. A right caught him in the jaw, though, and Bowen fell back and “his head hit the wooden floor with a thud which could have been heard a block away.” The ring, as it turned out, was not padded; it was simply wooden planks, with a canvas tarp stretched across the top.

In the early coverage of the fight, Bowen’s condition was reported to be improving, though he had not regained consciousness and “since the knock-out [had] not spoken a word.” Pokorny’s shoes ran their usual ad, in which the winning fighter was revealed to be wearing the local manufacturer’s boxing footwear (made from “the finest kangaroo”): “They stood him in good stead and carried him bravely to victory.”

No one seemed to anticipate that Bowen might die. His fall was compared to Jim Hall’s (who happened to be seconding Lavigne this night) the previous year, from which the fighter recovered. It was recollected that the Australian Young Griffo was once unconscious for four hours following a bout. Bowen showed signs of life in his dressing room—his hands continued to work, as if fending off opponents or delivering blows, and this was seen as a “favorable omen.” He vomited up undigested peas. Doctors administered whiskey, which raised his pulse rate from thirty-two to seventy. An ambulance was summoned, but fears that a hospital admittance might create negative publicity for the sport kept him from there. In one report, Bowen was passed through a hospital on his way home; in another, the unconscious pugilist was dispatched straight to his small house on Thalia Street; in both, his wife, Mathilde, waited anxiously.

Bowen lingered for several hours while a crowd gathered outside his gate. His wife implored him to speak to her, but he died close to dawn without having regained consciousness. “There was no further need of time-keeping for poor Andy,” the Picayune declared.

“PUT TO SLEEP” FOR ALL TIME THE FIGHT WAS TO A FINISH

The principal fight participants were brought in to the Tenth Precinct station while Bowen was still unconscious. Confident that the boxer would recover, “the prisoners took their arrest lightly, singing, joking and laughing over the style of work they would be put to if sent to the penitentiary.” At 2:45 a.m. Duffy was added to the group. After Bowen’s death became known, George “Kid” Lavigne was charged with his murder at 8:30 a.m., and held on a $10,000 bond; Duffy and six others were booked as accessories and held on $5,000 bonds. The group sent a telegram of condolence to Bowen’s wife, proclaiming that “no one regrets this fatal termination more than we do, and we hearby extend you our deepest sympathy in your bereavement.” They also made it clear they believed the wooden floor to be the culprit, not Lavigne’s fist. Indeed, the city coroner determined that Bowen’s death was accidental, caused by a concussion of the brain, and blamed on the hard floor; local newspapers published detailed autopsy accounts. Bowen’s autopsy is entered in the Coroner’s Office:—Record of Views (“Occupation: pugilist . . . Time in the City: Life”). The prisoners were eventually released.

There was no shortage of opinion over the cause of Andy Bowen’s death. Most held the unpadded floor responsible. (It was reported that Bowen had passed the club on a day prior to the fight and noted the lack of padding and thought it insignificant.) Some blamed Duffy for not stopping the one-sided affair, particularly the Daily Item: “[T]he referee and not the other principal is the person responsible to God and man for Andy Bowen’s death.” Duffy agreed that the fight should have ended sooner, but stated that Bowen’s seconds should have “thrown up the sponge,” and that he had no power to tell them to do so.

Duffy (among many) felt that Bowen was out of sorts from the get-go, and the fact that he vomited up undigested peas pointed to indigestion, thus causing his lackluster performance in the ring. This was a common argument that followed many boxing deaths at the time; one pugilist’s death, for example, was blamed on the “hearty dinner [eaten] shortly before he entered the ring” and its “resultant indigestion.” In another, a fighter’s “meningeal hemorrhage” was “occasioned by undue mental excitement and over exertion.” The ultimate failure of medical science to save lives within the pretense of a “scientific” sport threatened boxing’s progressive image.

Proponents of late-nineteenth-century boxing often found themselves defending their sport by blaming deaths on external causes, by citing the numerous accidents in the newer sport of football, and, though it contradicted a penchant for order, by pointing to the inherently accidental nature of their world at large. “Don’t men die by drowning and falling off of housetops every day?” Duffy asked. “A man at the opera, or dancing with his sweetheart, might fall and meet the same fate if the same combination of circumstances arose . . . Accidents are a part of the world, and death is waiting for all men as surely in one place as in another.” But Duffy was also a pallbearer, and despite his practical philosophy, lamented, “[N]ow I’m awful blue about this. Really I don’t think I could find words to say just how badly I feel, first for Andy and then for the women he leaves down here behind him.” He was also reported to remark, “[E]ver since the said affair happened I am literally all broke up.”

Despite his random and senseless death, Victorian visions of order still persisted in the press coverage of Bowen: his tidy cottage, where pictures hung neatly on the wall. That he was a family man, and lived an upright life, never drinking or gambling to excess; all these were published facts. But boxing’s image in New Orleans was decimated. Even at its height, the sport’s opponents had continued their crusade, particularly in the courts. Now the outcry over the popular Bowen’s death was enough to undo boxing in the city. “The killing of Andrew Bowen in a prize fight in this city Friday night should sound the death knell here of that bloody brutality misnamed ‘sport,'” the Daily Picayune declared. “The fistic carnival is over. It ended in a murder.” Bowen’s fatal bout would be the last legal, professional fight in New Orleans in the nineteenth century.

IV. Duffy’s Last Fights

John Duffy tried to revive the spirit of pugilism in early 1897, when he matched Joe Green (the black bricklayer who had been involved in the fatal fight at his saloon in ’93) against the “Terrible Swede” in a clandestine match on the banks of the Mississippi, somewhere upriver and out of Orleans Parish. About a hundred men paid $5 and boarded a steamboat (the Mabel Comeaux); when the bread and sardines ran out, many “tried to drown their hunger at the boat’s bar, and several succeeded in loading their stomachs with alcoholics.” At the first stop in Jefferson Parish, the sheriff would not allow the match to take place. Late in the day, the boat finally pulled onto the banks of Morgan’s Place, St. Charles Parish. Having no time to construct a ring, Duffy ordered the men to shake hands and fight. In the third round, a stranger appeared, “his face red with anger,” and demanded that the fight be stopped, reportedly blustering “the idea of niggers fighting white men. Why, if that darned scoundrel would beat that white boy the niggers would never stop gloating over it, and as it is, we have enough trouble with them.” The stranger, Henry Long, galvanized a group of supporters and the fight was halted, and the sports headed back to the city “sorry that they ventured on the trip.”

That October, a twenty-round charity exhibition match to benefit yellow-fever victims was arranged, with Duffy as referee, at the Tulane Athletic Club; no prize money was involved. Two amateurs, John Cummings, a motorman, and Walter Griffin, a clerk at the Illinois Central Depot, were matched to fight under a police watch. A speaker told the crowd that they “could not expect brutality and heavy slugging” and called for “perfect order” from the sports. Cummings received a rough beating, though he was still taking punches and staying on his feet or on his knees. Someone in the crowd cried out to stop the fight, but it continued until Cummings was knocked out; he died within hours from “many blows to the head, which probably ruptured a blood vessel.”

This was the third death on Duffy’s watch, and again he came under fire for not ending the bout sooner, but the referee later said that he “never thought for a moment such an end would come to the battle.” “I could not have afforded to have the mill continue, if I had dreamed of such a termination,” he explained. “Referee Duffy Would Rather Have Set Fire to the Building Than Forced the Fight to Death” the Picayune proclaimed. Griffin was charged with manslaughter but released since the fight had been under police regulations; he then promised his mother that he would never fight again, and said that he “would never get over the disaster which befell Cummings.”

It was clear the spirit of pugilism had left New Orleans. Indeed, professional boxing had already taken hold elsewhere: in Chicago and Buffalo and other cities, and, especially, in the athletic clubs of Manhattan, and the arenas of Coney Island. Title fights sprang up in random western outposts, like Carson City, Nevada, and across the Rio Grande from Texas. Rules and regulations were refined; weight divisions solidified. By the close of the century, the sport had been “absorbed into the hegemonic culture,” according to Elliott Gorn, as middle- and upper-class men, feeling an increased sense of powerlessness in the “tightly controlled” workplace and perceiving “the artificiality and stuffiness of modern life,” lived vicariously through the heroics of working-class, celebrity pugilists. By the 1920s, boxing would not only become an acceptable, even wildly popular, spectator sport for the bourgeoisie, it was big business as well, and fight promotion was a profession in its own right. All of these changes in the modern Queensberry realm of pugilism first publicly emerged, and took tenuous steps, in New Orleans.

John Duffy would not live to see his sport evolve; he took to bed in July 1898, and lay there for six weeks before he died, of cirrhosis, at the age of thirty-four. Captain Lee of Fire Company No. 5 tended to him in his sickness at his house on Julia Street (Duffy’s wife Kate had died in April of tuberculosis). His four children were sent to St. Michael’s Convent. Duffy had been supporting himself and his family with a job as lieutenant of night inspectors at the customs house; at the time of his death, the Professor’s friends (ninety-six of them) had been planning a benefit for him, which was then carried on for his children. “Even in his last days he was fully conscious of his approaching end, and thought of the famous ringside battles at which he had officiated.” Former mayor John Fitzpatrick, who had called for an end to boxing in New Orleans when Bowen died, was a pallbearer. At John Duffy’s funeral “there were men from all walks in life who had been his friends and admirers when he was at the zenith of his glory.”

Further Reading: For overviews of the New Orleans fight scene see Jeffrey T. Sammons, Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society (Urbana, 1990); Dale A. Somers, The Rise of Sports in New Orleans, 1850-1900 (Baton Rouge, 1972); William H. Adams, “New Orleans as the National Center of Boxing,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 39 (1956). Nineteenth-century boxing in the U.S. is explored in Elliott J. Gorn, The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting in America (Ithaca, 1986) and Michael T. Isenberg, John L. Sullivan and His America (Urbana, 1988). Gail Bederman’s Manliness & Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 (Chicago, 1995) uses the boxer Jack Johnson to explore issues of masculinity and race. For boxing history reference, see James B. Roberts and Alexander G. Skutt, The Boxing Register: International Boxing Hall of Fame Official Record Book (Ithaca, 1999) and Nat Fleischer and Sam Andre, A Pictorial History of Boxing (New York, 1959).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.2 (January, 2003).

Melissa Haley is a manuscript archivist at the New-York Historical Society. Her ancestor, Patrick “Patsy” Haley, fought professionally as a featherweight in the late 1890s.