Stubborn Loyalists

Calling on the daughters of Dr. Byles

In 1776, the Reverend Mather Byles was a nuisance to the rebels, and his Loyalist politics got him fired by his congregation at the Hollis Street Church. In 1777, his puns and wisecracks about the rebel cause got him arrested and convicted of being a dangerous person. The Committee of Safety, charged by the citizens of Boston with maintaining civil order during the Revolutionary crisis, sentenced him to house arrest and posted an armed guard at his home. But by 1820, that war had long been over, and Mather Byles had long been dead. Only his two daughters, Mary and Catherine, unmarried seamstresses, one seventy, the other sixty-seven, remained in the old family house, living private lives with little money and no political influence. One might suppose that by then, nearly a half-century after Lexington and Concord, bitter memories in Boston of the Loyalism of the Byles family would have faded, passions cooled. Still, the Revolution was a civil war. Do the embers of civil wars ever entirely cool? Observe this anonymous letter, received by the sisters in 1820 and carefully preserved in their files.

Dear old maids,

You who are paupers yet profess the contemptable [sic] kingly opinions of your tyrannical father—you would be more proud to kiss the hand or great toe of the fornicator George the fourth than perform the command of Deity Increase and multiply and replenish the earth—you who think more of family descent than goodness—poor weak simple dried up old virgins who does not despise you and your contemptable [sic] opinions. The writer gives you notice that unless you alter your proud course of conduct within one month your old rotten house shall totter and your first warning will be broken glass.

My sister has a box of extraordinary things such as are not to be seen every day.

Shortly thereafter, Mary and Catherine awoke to find their property vandalized and their trees hacked. But such assaults only stiffened the backs of the stubborn sisters and made them increasingly defensive—many people said increasingly proud—about their family history and their father’s reputation. After all, they did have contemptible opinions. Through the presidencies of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Jackson, Mary and Catherine obstinately, fiercely stuck to their convictions, insisting until their deaths—Mary’s in 1835, Catherine’s in 1837—that they remained loyal and unrepentant subjects of the British Crown who had been robbed of their rights as Englishwomen and marooned on a hostile peninsula on the shores of Boston Bay.

Despite this ugly anonymous letter, a small circle of friends occasionally came to tea and now and then helped them financially with a gift or by bringing them some sewing. Lydia Maria Francis, the young novelist fresh from the publication of Hobomok, insinuated herself with these friends, gaining an invitation to call upon the sisters. She had planned to write a novel about the Revolution, and she turned to the sisters for family stories about the siege of Boston and about their father’s famous wit. Francis’s meetings with the sisters persuaded them that in this young American novelist they had finally found a sympathetic soul who would honor them and their parents for courageous adherence to principle and who would, at last, grant their father the courtesy he deserved. But when the novel appeared in 1825, Catherine and Mary found Mather Byles mocked and his enemies celebrated.

The novel, entitled The Rebels, was also a surprise to the young novelist; although she might have anticipated the Byles sisters’ reaction, she could not have imagined that some of Boston’s prominent families would turn positively frigid towards her. They thought that Francis had behaved unscrupulously by gaining the sisters’ trust and then abusing it. Making matters worse, several families found their own ancestors targets of heavy-handed satire in The Rebels. Politics aside, Miss Francis had unwittingly outraged old Boston’s sense of propriety, and Boston had its ways of punishing social offenders. Humbled, she wrote the sisters an apology. It is a strange rhetorical mélange of contrition and self-justification. Shortly thereafter, the young teacher Elizabeth Palmer Peabody noted in her journal that the Byles sisters had replied to Francis with “a very dry note, refusing to see her.” But they did assure her that “they hoped to meet her in another world”—and they made sure to keep Miss Francis’s letter.

In 1833, the well-known Philadelphia writer Eliza Leslie came to Boston, hoping to meet the now legendary daughters of Dr. Byles. A visit was arranged, but evidently nobody had briefed her about what to expect at the house on Byles’s Corner, near the Boston Neck and a short walk from the Hollis Street meetinghouse, where Mather Byles had been dismissed long ago. Burned before by a visiting writer, the sisters had not forgotten. Miss Francis had confirmed their belief that in a republic, the word of a lady or a gentleman cannot be trusted. Still, the friend who had asked them to receive Miss Leslie was a dear person, a Bostonian who had always generously assisted them. One could hardly deny her this favor. But be wary.

Eliza Leslie was shocked to see the old house on Byles’s Corner. Frame, plain, and black as iron, it looked forbidding among the other dwellings of modern Boston. Cracks and chinks gave the board fence surrounding it a dilapidated air; the gate dangled by a leather string. The front steps were decayed and collapsing. Yet, on that mild summer morning the lot was green, with wild flowers amid the grass. Two giant horse-chestnut trees threw deep, pleasant shadows on the roof and walls. As Leslie and her companion walked up the narrow path to the doorway, they thought they saw a female figure hastily flitting away from the front window.

Their knock was answered immediately by Miss Mary Byles, a broad-framed, smiling old lady dressed in a black worsted petticoat and a white short-gown with a muslin kerchief tucked at her neck. Her full-bordered white linen cap nearly covered her smooth white hair. She ushered her guests into the parlor, where they encountered bare floors and a few pieces of very old furniture. Miss Leslie’s companion inquired about the health of Catherine Byles, and Mary ruefully said that her sister was quite unwell, having passed a bad night with rheumatism. As Miss Leslie and her companion sat a bit nervously in the parlor, they expressed regrets at missing the chance to meet the younger sister, but while they murmured in disappointment the door suddenly opened and Miss Catherine swept into the room, greeting her visitors warmly and dismissing her rheumatism with a smile. She also wore a black bombazine petticoat, a short gown, and a close-lined, bordered cap, but her appearance differed markedly from Mary’s. Catherine, wrinkled and thin, had sharp, angular features.

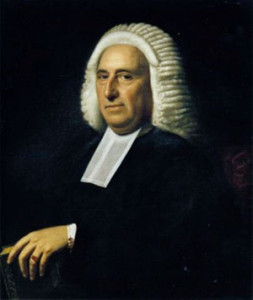

The sisters immediately directed their visitors’ attention to a magnificent portrait of their father done years earlier by John Singleton Copley, pointing to Dr. Byles’s signet ring with its splendid red cornelian—an exact likeness of the ring itself. They turned next to a self-portrait of their nephew, the now famous portraitist Mather Brown. Though the sisters lamented that they had not seen the poor boy for nearly forty years, they knew of his huge success in England. Why, Catherine had given him his first drawing lessons while he lived with them in the years before their father had lost his pastorate and salary. When the rebels convicted and sentenced Father, he had no money to keep young Brown, so the boy went off at age fifteen to follow the army camps, making his way as a painter of miniatures. Later, their father’s influence, and that of his boyhood chum Benjamin Franklin, got Brown to England, where he would study with the great history painter Benjamin West. He became so admired that he even painted the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York! But he never forgot his Aunts Polly and Kitty. Look closely at the self-portrait. In his hand he holds an open page containing the very words of a letter Kitty had sent him!

“What would have happened,” Catherine asked, “if we had been able to persuade Father to give up America and move to England at the end of the war?”

“Why, in that case,” Mary answered, “we should all have been introduced at court; and the king and queen would have spoken to us and, I dare say, would have thanked us for our loyalty.”

After showing her the paintings, Mary Byles invited Miss Leslie to sit in a great, black, oaken armchair, which had been sent from England more than a century earlier as a present to their maternal grandfather, Governor Tailer. It was elaborately ornamented, with a carved crown on the top of the back. Its velvet cushion, Mary explained, was always kept upside down to preserve it—but for her guest’s comfort, she turned it right-side-up so that Miss Leslie might sit upon velvet.

“Do you find it an easy seat?” inquired Mary.

“Oh, yes, indeed, quite easy,” replied Miss Leslie.

“I am surprised at that,” rejoined Mary. “I wonder how a republican can sit easy under the crown.”

Startled, Miss Leslie did not quite know how to reply to this unexpectedly political pleasantry—but then she saw Mary and Catherine exchange a smile.

Catherine next brought Miss Leslie to the very table where Dr. Franklin took tea on his last visit to Boston. While the guests admired the curious table, Mary dragged from a closet a huge, intricately carved, iron-and-timber bellows, which she judged to be two hundred years old and which she invited her visitors to work—but it was so heavy that only a very strong man could have done so.

Then Mary turned to Catherine and asked, “Have you no curiosities to show the ladies?”

“Nothing, I fear, that the ladies would care to look at.”

“To the contrary,” said Mary, “my sister has a box of extraordinary things such as are not to be seen every day.”

Thereupon, Miss Leslie’s companion begged the sisters to permit their Philadelphia visitor a glimpse of Miss Catherine’s collection of curiosities. After a little coaxing, Catherine produced a square bandbox. She took from it the envelope of a letter to their father addressed by Alexander Pope himself. There were four commissions, each bearing the signature of a different British sovereign at the top of the document—demonstrating, Catherine explained, that royalty comes before everything else. One bore Queen Anne’s signature; another, George I’s; another, George II’s; and George III’s graced the last. The next treasure was a piece of moss gathered from the roof of Bradgate Hall, the birthplace of Lady Jane Gray, whose brief nine-day reign preceded Queen Mary’s. The last was an artificial mulberry that looked surprisingly real.

“And now,” said Catherine, “I will show you the greatest curiosity of all.” She removed an inner pasteboard box that fit within the larger one, set it on the floor, and took from a round hole in the lid an artificial snake. With some mysterious twist, she set it in motion, and it ran about in the neighborhood of Miss Leslie’s feet. After all had remarked on its ingenuity, Catherine told the snake that it was time to go home. As she returned it to its box, it seemed to wiggle away.

“What!” said Catherine, giving the snake two or three smart taps, “Won’t you go in? Are you a rebel too?” Immediately, the serpent straightened and scurried back into its box.

“Now,” said Mary to Catherine, “won’t you show us your extraordinary trick, which always astonishes the ladies?”

“Oh,” replied Catherine, “if I were to do so, someone might learn of it and have me taken up and hanged for a witch.”

Everyone promised to keep the secret. Thereupon, Catherine tore a scrap of white paper into four small pieces and set them in a row on the table. Then Mary left the room, shutting the door tightly behind her. Catherine invited Miss Leslie to touch her finger to any piece of the paper. She touched the second. Catherine then called for Mary, saying as she entered, “Be quick.” Without hesitation, Mary advanced to the table and pointed to the second piece of paper. Miss Leslie, startled, asked to repeat the task. Again Mary identified the correct piece. And again. And again. Finally baffled by this non-witchcraft, the guests implored the two elderly sisters to reveal their secret. Delighted, they explained that the four pieces of paper denoted the first four letters of the alphabet. When the guest touched the second (B), Catherine greeted her sister with the phrase, “Be quick.” For the fourth, she said, “Do you think you can tell?” For the first, “Are you sure you can guess?” For the third, “Come and try once more.” The foolproof method never failed them.

Having been treated to the portraits, the easy chair, the table, the bellows, the museum of documents, the artificial snake, and the mystery of the papers, it seemed time for Miss Leslie and her companion to take their leave. Yet Mary and Catherine had a request for their visitors. Pincushions, needle-books, and emery bags covered a square table near one of the windows. This was their “charity table” where they sold items “for the benefit of the poor.” Miss Leslie thought that the Byles sisters were themselves their own poor, but kindly she decided to buy the ugliest needle-book she’d ever seen.

As Catherine exchanged parting pleasantries with her visitors, Miss Leslie glimpsed Mary slipping out into the short hallway leading to the house door and then back in again. Then Mary joined them and escorted them to the front door. Now, preparing for their final departure, the two visitors approached the front door. But it was locked! And it seemed impossible to unlock it! Mary turned the key this way and that, but the door would not open.

“Oh, dear,” said Mary. “The ladies will have to send home for their nightcaps, as they are likely to be kept here all night!” As the visitors exchanged alarmed glances at that prospect, Mary smiled slyly and gave the key a turn. The lock yielded; the door opened; Mary curtsied and smiled them out.

Making her way down the narrow path to the drooping gate, Miss Leslie remarked that she had just undergone one of the strangest experiences of her life. “Ah,” her companion replied, “I am afraid I have kept a small secret from you. I have had this experience before—precisely this experience. Every visitor has this experience the first time, without deviation. Miss Mary always receives guests at the front door; Miss Catherine always pretends to be indisposed but then makes her entrance. Visitors always see the Copley portrait and the cornelian ring, the self-portrait of Mather Brown is always exhibited and the letter noted, the new guest is always placed in the great chair to experience what it is like for a republican to sit under the crown, the sisters always take turns in producing one curiosity after another, culminating in Catherine’s box of documents, the trick snake, and the joke about the rebel snake; the astounding trick of the pieces of paper always occurs next, and whenever the visitors hint at departing, Miss Mary always slips out, locks the front door, and slips back in to conduct her little hoax and tell her joke about the ladies’ nightcaps! Only after you have survived this piece of theater will you have any chance for a conversation with them about Loyalism during and after the American revolution.”

“So you knew all along what they were doing? Even the trick with the paper?” Miss Leslie asked.

“Yes, of course. There is no other way. And now you know. You did very well. I am sure they will see you again if you ask to call.”

Miss Eliza Leslie did call again. Subsequently, she reported, the sisters “were infinitely more rational than when ‘putting themselves through their facings’ to show off to strangers.” In “the course of these quiet conversations,” Leslie recalled, “they told me many little circumstances connected with the royalist side of our revolutionary contest, that I could scarcely have obtained from any other source.” Mary and Catherine, she wrote, “gloried—they triumphed, in the firm adherence of their father and his family to the royalty of England—and scorned the idea of even now being classed among the citoyennesof a republic; a republic which, as they said, they had never acknowledged and never would; regarding themselves still as faithful subjects to the majesty of Britain, whoever that majesty might be.” In an upper room, they displayed portraits of themselves at ages seventeen and eighteen, painted by the famed English portraitist Henry Pelham. She saw the family silver, their father’s scientific instruments, and his extensive collection of rare books. They had rejected all invitations to sell anything, even to Harvard College.

Then there were the personal anecdotes. They recalled that as young women they walked on the Boston Common with General Howe and Lord Percy, and the regimental band serenaded them under the horse-chestnut trees. They knew George IV when he was in Boston as Duke of Clarence and an officer in his father’s navy. They had even written him a letter of congratulation when he became King, assuring him that they, the surviving members of the family of Dr. Byles, remained truly and fervently devoted to the rightful sovereign. They remembered fearing starvation during the siege, but they recalled that after they had given a hungry British soldier a piece of pork, he returned a few evenings later to slip Mary a packet of “the detested tea” as a token of his gratitude. They spoke of their pain in seeing the Hollis Street meetinghouse converted to a barracks and in seeing the Old North Church torn down for firewood. They recalled that during the last days of the siege they darkened their house and kept their shutters drawn because the American artillery used the house as an aiming point. They recalled their bitterness and anxiety during their father’s imprisonment in his own home, their lonely separation from their relatives in Halifax, and their isolation from the rest of the town. Living in the strictest abstemiousness, they subsisted on two hundred dollars per year and on the charity of friends. By frugality, they managed to save most of their two hundred dollars; they donated a portion of that, along with the proceeds from their charity table, to the poor. They seldom went out, except—bonneted and heavily veiled and always in the same Sunday clothes—to services at Trinity Church, and they continued to dress in the fashion—indeed, in some of the same clothes—of 1776. For years they had conducted a running dispute with the city of Boston, which wanted to open a street through their property. They resisted the pressure from city officials to sell their land as they had resisted offers to buy their treasure chest or box of curiosities.

Eventually, they lost that dispute. To make room for the street, Boston exercised its rights of eminent domain, taking half the Byles’s yard and half the house. The sisters refused to vacate during the demolition. “They mourned over the departure of every beam and plank as if each was an old friend,” wrote Eliza Leslie, “and deep indeed was the affliction of the aged sisters when they saw, falling beneath the remorseless axe, their noble horse-chestnut trees, whose scattered branches, as they lay on the grass, the old ladies declared, seemed to them like the dismembered limbs of children.” Within a year, Mary was dead. Catherine insisted that her sister had died of a broken heart. She had always hoped to die, as she had lived, in her father’s house just as he had left it. “Poor sister Mary,” said Catherine. “She soon fretted herself to death.” And Catherine knew the source of this final indignation. “Ah,” she said, “this is one of the consequences of living in a republic. Had we been still under a king, he would have known nothing about our little property, and we could have enjoyed it in our own way as long as we lived. There is one comfort, that not a creature in the states will be any the better for what we shall leave behind us—Sister and I have taken care of that. We have bequeathed every article to our relations in Nova Scotia, since our nephew, poor boy, was so unfortunate as to die before us. In all our trials it has been a great satisfaction to us to reflect that when everything was changing around, grace has been given to us to remain faithful to our church and king.”

And they had taken care of it. At Catherine’s death everything—including the Copley and Pelham portraits and the voluminous file of correspondence they had quietly conducted for sixty years—was crated and shipped to Halifax, where it was divided among members of the family and subsequently scattered all over Canada—a situation calculated to make a researcher fret himself to death.

Further Reading:

The anonymous 1820 letter and the 1826 letter from Lydia Maria (Francis) Child are printed from microfilm copies at the Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management (Almon Family Fonds, Series G, Subseries 2, No. 89 and Series A, No. 29; originals held by Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa). Mary Tyler Peabody discusses the Child/Byles incident in a March 22, 1826, letter to Rawlins Pickman (Horace Mann II papers, Massachusetts Historical Society). Mary and Catherine Byles’s reply to Child is mentioned in the journal of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody for September 22, 1826, as extracted by Mary Van Wyck Church in her manuscript biography of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody (Massachusetts Historical Society). Footnotes in Carolyn Karcher’s The First Woman of the Republic: A Cultural Biography of Lydia Maria Child (Durham, N.C., 1994) and Megan Marshall, The Peabody Sisters (New York, 2005) helped steer me to these unpublished sources. Child’s fiction has recently been rediscovered and freshly appreciated. Carolyn Karcher has edited a paperback edition of Hobomok and Other Writings on Indians (New Brunswick, N.J., 1986); she has also published A Lydia Maria Child Reader (Durham, N.C., 1997). Eliza Leslie, although she wrote voluminously in many forms, is best known for her nine cookbooks. One of them, Directions for Cookery, in its Various Branches (Philadelphia, 1837), was the best-selling cookbook of the nineteenth century. My account of her visit reconstructs events she reports in her article “The Daughters of Dr. Byles: A Sketch of Reality,” from Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine 20 (1842): 61-65; 114-18. Arthur Wentworth Eaton’s The Famous Mather Byles (Boston, 1914) and the biographical sketch of Byles by Clifford K. Shipton, reprinted in New England Life in the 18th Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1963), remain the chief sources of information about him. For Mather Brown, see Dorrinda Evans, Mather Brown: Early American Artist in England (Middletown, Conn., 1982). The standard histories of the American Loyalists are Wallace Brown, The Good Americans: The Loyalists in the American Revolution (New York, 1969); Mary Beth Norton, The British-Americans: The Loyalist Exiles in England, 1774-1789 (Boston, 1972); and Robert M. Calhoon, The Loyalists in Revolutionary America (New York, 1973).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.4 (July, 2007).

Edward M. Griffin is professor of English at the University of Minnesota. Having written a biography of a prominent patriot clergyman—Old Brick: Charles Chauncy of Boston, 1705-1787—he has now taken up the opposing side with a biography-in-progress of Chauncy’s Loyalist rival Mather Byles, 1707-1788. He is also editing the unpublished letters of Byles’s Loyalist daughters, Mary and Catherine.