Suffrage and Citizenship

Among the most cherished rights of American citizens is the right to vote. No wonder we hear cries of alarm when legislatures raise barriers to citizens’ voting. The right to vote is widely recognized as fundamental to citizenship; and its denial to non-citizens seems axiomatic. If we allowed “foreigners” to vote, many believe, we would endanger our democracy. But as Americans consider the proper way to qualify voters and how to apportion representation, it is worth being reminded that U.S. citizenship and suffrage have not always been two sides of the American coin. Indeed most Americans, Supreme Court justices probably included, would be surprised to learn that the voters who elected presidents from George Washington to Abraham Lincoln included many thousands who were not United States citizens.

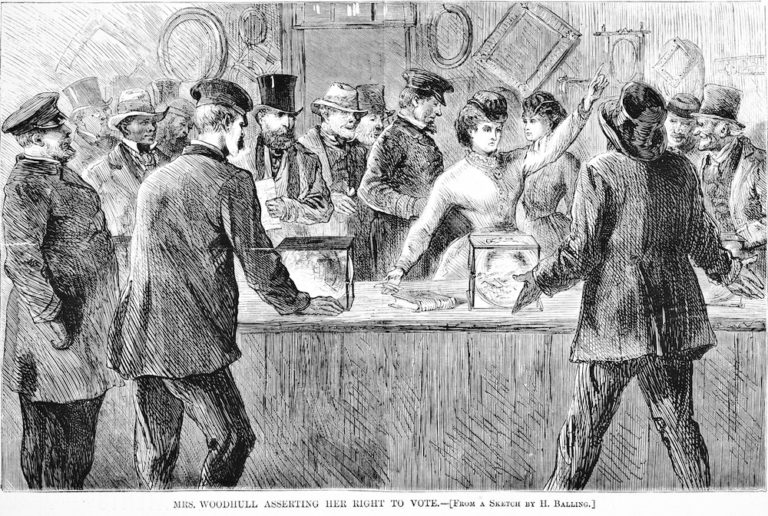

While Woodhull is denied a ballot an African American, an Irishman, and a German—identified stereotypically—vote, as well as a miscellany of other men.

In 1773, when Patriots dumped East India Company tea into Boston harbor, the colonists cried “No taxation without representation!” Though Parliament had cut the tax on tea, Patriots protested because no matter what the tax rate, Parliament did not represent them. Patriots were willing to pay taxes, and paid them every year, but only when voted by a majority of their elected representatives. No principle was dearer to American Revolutionaries than the bond between representation and taxation. They reasoned that if government could take their property arbitrarily, government could reduce them to begging food and shelter for themselves and their families. Secure possession of property was the necessary guarantor of liberty.

This is why twelve of the thirteen original United States stipulated that representation must belong to property holders, and denied suffrage to those who did not own property. After all, leaders reasoned, if poor men could vote they would seize prosperous men’s property. One state, Pennsylvania, thought otherwise, judging that every man paid taxes one way or another, and all, rich and poor, had a stake in society. Moreover, with warfare underway, why should men with no representation fight to defend rights they were denied?

In time, state after state came to adopt Pennsylvania’s reasoning. Americans learned that extending suffrage to poor men did not lead them to confiscate wealth or redistribute property. Instead, by ending property requirements for voting, states enhanced the legitimacy of governments. By the 1830s, free white men could vote in virtually every American jurisdiction. Those who were widely barred from voting—slaves, free African Americans, and women, like youths—were understood to be “dependents” subject to the will of others at the polls.

But for white men, the only generally required qualification for voting was one year of residency, two at the most. What began as a restricted republic of property holders became a white men’s democracy. Most remarkable from the perspective of 2016, there was no uniform requirement that voters be United States citizens, or even citizens of the state where they resided. As Alexander Keyssar reported in his The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (2000), as of 1855, though eighteen of the nation’s thirty-one states did require U.S. citizenship to vote, two (Ohio and Rhode Island) had only added that stipulation in 1851. Three states (Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin) explicitly stated that foreigners could vote if they intended to become citizens. And ten more, mostly the original states formed during the Revolution, demanded state citizenship only. When Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860, tens of thousands of foreign immigrants who were not U.S. citizens were voting in states from the Carolinas and Virginia to New York and Massachusetts, and west to Indiana and Michigan. The Revolutionary cry, “No taxation without representation,” remained central to voting rights, even more basic than national allegiance.

As American legislators ponder the regulation of suffrage, it would be well to remember that erecting barriers to the franchise does not reflect the long history of voting in the United States, and has instead been connected to efforts to shape the character of the electorate. Initially propertied people feared that their property-less neighbors would re-distribute wealth. Then there was a fear that women and non-whites would corrupt the integrity of the electorate. Later that concern shifted to foreigners. Whether or not we believe there is such a thing as “the integrity of the electorate,” we need to recognize that from the beginning the foundation of voting rights was taxation: the belief that those who are taxed should have a voice in the disposition of their property. How far we choose to honor that ideal has been more a matter of practical politics than a matter of principle.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.4 (September, 2016).

Richard D. Brown, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of History emeritus at the University of Connecticut, is the author of the forthcoming Self-Evident Truths: Contesting Equal Rights from the Revolution through the Civil War (Yale University Press, 2017). He is co-author of two microhistories: Taming Lust: Crimes Against Nature in the Early Republic (2014) with Doron S. Ben-Atar, and The Hanging of Ephraim Wheeler: A Story of Rape, Incest, and Justice in Early America (2003) with Irene Quenzler Brown.