The Tao of John Quincy Adams

Or, new institutionalism and the early American republic

Any political consultant worth their salt would see that John Quincy Adams had many liabilities, but the vision thing was not one of them. As the candidate who finished second in both the popular and electoral vote, Adams enlisted the aid of Henry Clay and a host of other allies to win the presidency after the election of 1824 was thrown to the House of Representatives. When the smoke cleared in February of the following year, Adams was president. One would think that a president elected by only 31 percent of the popular vote might ease into his first term. But this was John Quincy Adams. In his (in)famous first message to Congress in December of 1825, Adams forcefully outlined the philosophy of a group of like-minded politicians known to historians as the National Republicans. “The great object of the institution of civil government is the improvement of the condition of those who are parties to the social compact, and no government, in what ever form constituted, can accomplish the lawful ends of its institution but in proportion as it improves the condition of those over whom it is established.” For Adams and his followers this meant a dramatic new role for the national government. Federal funding for an ambitious program of roads, canals, and river improvements, a national observatory, a national university, a new naval academy, tighter patent laws, and even a new marble monument to George Washington all stood on Adams’s to-do list. After outlining these grandiose plans, Adams veered into a rhetorical ditch. As the president with perhaps the least electoral support of any in the young nation’s history, Adams stood before Congress and wondered if we were “to slumber in indolence or fold up our arms and proclaim to the world that we are palsied by the will of our constituents, would it not be to cast away the bounties of Providence and doom ourselves to perpetual inferiority?” With these ill-chosen words about the needs and wants of American voters, Adams offered his critics the choicest of political plums. Here was proof that the sixth president of the United States was out of touch with the nation’s increasingly expanded and fractious electorate.

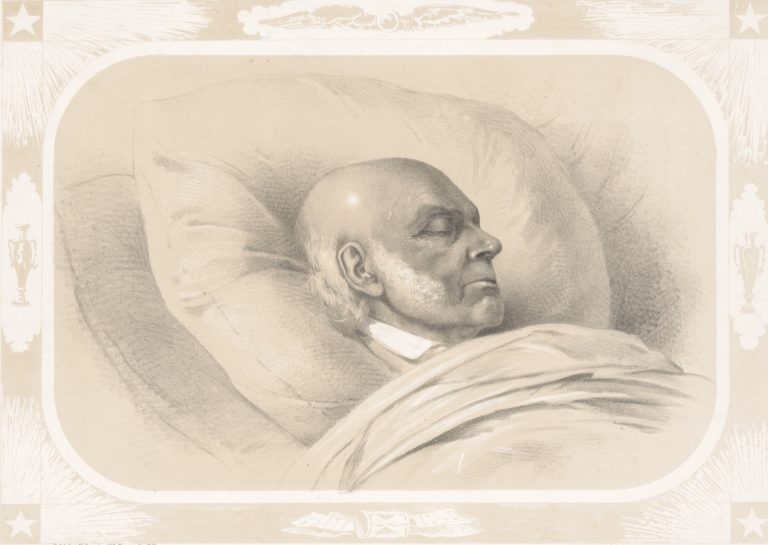

Adams’s apparent misreading of the political winds not only contributed to the demise of the National Republican agenda, it also helped transform a former ally, General Andrew Jackson, into Adams’s greatest ideological opponent and political rival. Once in office, moreover, Jackson’s policies rolled back any attempt by his predecessor to expand the government by building the sorts of institutions Adams had described shortly after taking office. Old Hickory vetoed the Maysville Road, slew the Monster Bank, and took the motto of the Washington Globe, “The World Is Governed Too Much,” generally to heart. If there was to be a bureaucracy at work in public life, Jackson’s followers argued, it should be a well-oiled party apparatus devoted to electing good Democratic candidates to office, instead of state or federal bureaucrats devoted to some fuzzy notion of “improvement.” Jackson’s historical legacy continues to overshadow that of Adams. After all, Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s classic book defined the period of Jackson’s political ascent as “The Age of Jackson,” and the general looms as the dominant figure in the work of such authorities on the period as Robert Remini, Sean Wilentz, Andrew Burstein, Harry Watson, and Charles Sellers. A quick perusal of the more specialized political history written on the period suggests that even when the general is not personally involved, the Jacksonian emphasis on party formation—as opposed to the formation of government institutions or the “state”—often dominates accounts of antebellum public life. Daniel Walker Howe’s recent Pulitzer Prize-winning survey of the early republic, What Hath God Wrought, is one important departure from this tradition—in fact Howe dedicates the book to Adams—but there is no mistaking the impact that Jackson and his followers left upon this pivotal period in American history. Andrew Jackson usually elicits a strong and divisive response among scholars; they admire or resent his strong personality and forceful policy decisions with only rare equivocation. Jackson’s hostile attitude toward public and private institutions, however, has been less a source of contention. Whether denouncing the antidemocratic tendencies of the business corporation or cataloguing the long history of unwanted and inefficient state regulation of the economy, Old Hickory’s ideological imprint still influences the way we Americans regard institutions, whether we admire Andrew Jackson or not.

Yet, as much as Americans of his time and ours might share Jackson’s deep suspicion of banks, corporations, and government itself, there is reason to doubt that—despite Jackson’s electoral victories—his anti-institutional vision has been as influential as is often assumed. Indeed, given its tendency toward antislavery, the preservation of Native American treaty rights, and expanded participation for women in American society, the perspective of Adams and his allies—a group that would coalesce as the Whig party—seems in many ways much closer to the values of modern-day Americans than, say, the proslavery and anti-Indian tendencies of many Jacksonian Democrats. Recognizing the persisting resonance of Adams’s institutional perspective, some historians of the early American republic, Howe being the best known, have begun rewriting that period’s history. In so doing, they have initiated a sweeping reassessment of American politics and their supposed anti-institutional bias.

What exactly are institutions? Many disciplines struggle with this question. Ask, for example, an economist to define a “firm” or a political scientist to explain “the state” and this quickly becomes clear. You’re much more likely to get a lengthy list of scholarly citations than a clear and distinct answer. Nonetheless, we have to start somewhere. For the purposes of argument, let’s call an “institution” a formal set of rules within a prescribed boundary of authority. For historians, formal institutions like legislatures, corporations, banks, or political parties are visible remnants of political and economic tussles, cultural assumptions, and both formal and informal power arrangements. These institutions are also remade countless times over the course of their existence, adding a healthy dose of contingency to the mix. Internal actors constantly reinterpret the ways policies are made and enforced, while external actors can expand, contract, or ignore an institution’s capacity for enacting those policies. Rather than static entities, institutions often undergo a process not unlike the kind of “punctuated equilibrium” described by evolutionary biologists: rapid changes in their internal structure or environment trigger small changes that, with time, come to constitute dramatic institutional transformations.

When scholars began recognizing these evolutionary qualities, they put the “new” in “new institutionalism.” In place of an older view of institutions as static, conservative entities, they substituted a new perspective that recognized the contingent and dynamic nature of institutions. Now, instead of antiseptic and ahistorical entities, institutions became intensely historical and capable of dramatic and dynamic change. This perspective should complement, rather than counter, the many insights made by an earlier generation of historians more concerned with the social and cultural lives of ordinary people. For these scholars, institutions such as “the state,” “firms,” or “slavery” often assumed cardboard-like qualities, standing as crude extensions of the interests of a particular group—the ruling class, managers, or slaveholders, for example. Indeed, the institutions of the early republic did often reflect the needs and desires of elites, but reducing them to pure instruments of their collective will lacks historical accuracy and replaces the complexity of institutions with a simple straw man begging to be knocked down. By emphasizing the dynamic and contingent nature of institutions, the new institutionalism offers a way to avoid this sort of instrumental reductionism and, more importantly, to expand the scope of our vision as we reconstruct the political, social, and economic landscape of the early republic.

The early American state is perhaps the most obvious place to look for the impact of the new-institutionalist approach. Not so long ago, the prevailing scholarly view was that there was no early American state—the government was a regime composed largely of courts and parties with little power beyond the collection of tariffs and the raising (barely) of an army and navy. The first serious revision of concepts of the American state began with a group of political scientists interested in what they called “American political development” (APD). Inspired by the call of the Harvard social and political theorist Theda Skocpol and other social scientists to “bring the state back in” to political analysis, APD studies argued that political scientists needed to emphasize the ways legislatures, courts, government agencies, and other political institutions are essentially historical constructions with all the contingencies, paradoxes, false starts, and inefficiencies associated with other historical actors.

Armed with the theoretical tools of APD, a new generation of political historians sought to reconstruct the antebellum political landscape. More specifically, they examined the ways state institutions were critical to economic development. Colleen Dunlavy’s comparative study of American and Prussian railroads looked at the “structuring presence” of the state in economic development. Richard John demonstrated how the antebellum U.S. postal system helped usher in a communications revolution and, in turn, made the federal government a crucial agent for binding together national markets. John Lauritz Larson traced the republican roots of internal improvements in the early republic. In doing so, he showed that early American canals, roads, and other improvements were not the products of an anti-statist, liberal, and Jacksonian ideology but rather owed their existence to an early republican vision. What this and similar work has shown is that the old idea of the passive and barely present state of courts and parties is unable to account for, in Richard John’s words, “governmental institutions as agents of change.” This insight not only reconfigures the political landscape of the early republic. It has the ability, as John’s work on the postal service demonstrates, to alter our conceptions of historical space and time.

The study of economic institutions is another significant area of new-institutionalist scholarship. Here Jackson’s legacy persists in modern American life as well. It is quite common to hear denunciations of banks, calls for “sound” fiscal and monetary policy, and the condemnation of large concentrations of wealth and power among contemporary pundits. Old Hickory’s populism might sell advertising space or boost polling numbers in the short run, but it offers a severely limited perspective for the historical study of these things. Take, for example, an institution that is quite commonplace: the corporation. Modern Americans are likely to view corporations, past and present, as the paragons (good or bad) of private-sector initiative, but this is an ahistorical view. In the early republic, corporations existed in a much more ambiguous sphere—neither purely public, nor purely private. And promoters of incorporation adeptly exploited this ambiguity, arguing that potentially profitable enterprises such as bridges and toll roads were fundamentally matters of public necessity. Such insights are evident in the work of a broad array of historians. Andrew Schocket’s recent book argued that elites used the corporate form of organization to forge alliances that crossed civic, business, and philanthropic lines to create a new “corporate class” in antebellum Philadelphia. John Majewski’s excellent comparison of economic development in Virginia and Pennsylvania stressed regional differences in public and private investment. As it turns out, the rural residents of both states enthusiastically supported banks and railroad corporations within their district but counted upon urban capital to fuel these critical ventures.

New-institutionalist studies have also incorporated the insights of social and cultural historians into their research. Naomi Lamoreaux looked at insider lending in banks in antebellum New England, allowing us to understand how capital formation can owe as much to informal social networks as to the invisible hand of the market. Edward Balleisen took a seemingly narrow institutional topic—the Bankruptcy Act of 1841—and turned it into a fascinating case study of the culture of failure during a formative period of American capitalism. More specifically, he examined the ways the antebellum surge in personal bankruptcies redefined the morality of failure and helped pave the way for the acceptance of corporate employment among middle-class Americans. Rather than narrowly focus on the corporation’s inherent or emergent economic efficiency—as many traditional business and economic historians were wont to do—these studies all place that critical institution within a wider social and cultural context.

Emerging research on other corporate entities such as savings banks and life insurance companies by Dan Wadhwani and Sharon Murphy promises to transform those reputedly stodgy institutions into accessible ones that are integrated into the mainstream scholarship on the early republic. Wadhwani studies the ways early savings banks—created with both philanthropic and financial objectives in mind—transformed the family economy by offering small earners a place for their savings. By allowing opening deposits as low as one dollar, the creators of these savings institutions sought to draw customers from a broad socioeconomic base. And, it turns out, they succeeded. Working families used these accounts for various purposes: to provide liquidity, smooth out the rough edges of seasonal employment, stabilize their household economy, and, in the case of many working women, save for old age. Murphy’s work demonstrates the significance of early life insurance companies in the construction of American middle-class values during the nineteenth century. In a recent article in The Journal of the Early Republic, she examines the ways slaveholders increasingly adopted life insurance policies for their “property.” In some of these cases, life insurance policies even facilitated emancipation by serving as a collateral loan while hired-out slaves earned enough money to purchase their manumission.

Although the new institutionalism has its roots in studies of the state, the approach also offers insights into topics that are of central concern to social and cultural historians. Consider slavery. One early-twentieth-century historian of Virginia likened slavery to “the watch which in spite of everybody persisted in keeping wrong time till the magnet secreted near the mainspring had been discovered.” His point was that slavery’s impact was often barely perceptible, but like the punctuated equilibrium that reshaped so many institutions, its long-term impact is difficult to overstate. These unexpected effects, like the “magnet near the mainspring,” suggest that even institutions as seemingly familiar and well-studied as slavery can have counterintuitive or little known consequences. Sally Hadden’s study of the slave patrol in the Upper South, for example, shows that American law enforcement as we know it owed a great deal to the antebellum slave patrols and their task of enforcing strict racial hierarchies in the countryside of Virginia and North Carolina. “The history of police work in the South,” she argues, “grows out of this early fascination, by white patrollers, with what African-American slaves were doing.” My own research on the early American coal trade explains how the wider political impact of slavery affected corporate chartering, transportation, and even scientific policies in antebellum Virginia. When the new state of West Virginia attempted to start their coal trade in a post-Civil War environment, they found it difficult to shake inherited institutional constraints on industrial growth—constraints that had been shaped by slavery in antebellum Virginia. The rise and fall of interstate highway signs touting West Virginia’s former state slogan, “Open for Business,” suggests that state policymakers still struggle to capture the coal industry’s elusive prosperity in the twenty-first century.

An exemplar of new-institutionalist approaches to the political economy of slavery is Robin Einhorn’s recent book American Taxation, American Slavery. Einhorn’s work brings tax policy—once the province of financial historians and the posse comitatus—to the historical forefront. She shows that tax regimes in southern colonial and state governments privileged slave owners at the expense of less wealthy whites. Once this aspect of government had been co-opted by slaveholding interests, any attempt to achieve a more just tax code became nearly impossible. Southern planters used the institutions of governance to empower themselves and achieve the political and economic ascendancy that has become so familiar a part of antebellum southern history. The remnants of these policy regimes are evident in modern-day southern politics, and just as recent historians demonstrate the persistence of social and cultural dialogues concerning race, Einhorn traces the institutional impact of slavery into the twentieth century and beyond. For those who live, work, and raise children in low-tax and low-service states, tracing the origins of woeful funding mechanisms for education back to the antebellum era might offer little comfort, but it nonetheless serves as a powerful example of the contemporary significance of institutional history.

There is much more to the new institutionalism than simply finding a state where previous scholars claim one did not exist. William Novak’s book, The People’s Welfare, establishes the strong role that public institutions played in regulating the lives of everyday Americans in the early republic through “overt policies of government and law [and] not the invisible laws of supply and demand.” For example, we often think of consumer protection as a product of the Great Society of the 1960s, but Novak demonstrates that basic consumer goods such as beef and pork, butter, bread, alcoholic beverages, leather, and gunpowder were all monitored by state officials much, much earlier. Massachusetts, in fact, passed regulations governing the production and sale of no fewer than twenty-six categories of consumer products between 1780 and 1835. When they shopped for their daily meals, traveled to other cities, or even unwound with an ale or cider at the end of the day, Americans of the early republic negotiated the institutional boundaries of public regulatory authority as much as they encountered the invisible hand of the market. New-institutionalist perspectives can link seemingly antiseptic concepts like “regulatory capacity” and “institutional context” to the contours of everyday life in the early nineteenth century. More importantly, this kind of scholarship demonstrates that the significance of institutions in shaping American life never quite faded away as much as Jackson and his ideological devotees would have liked.

The post-presidency career of John Quincy Adams, to come full circle, is perhaps the best indication of the limitations of Jackson’s anti-institutional posture. When he struggled to remake national institutions in 1825, President Adams witnessed firsthand the political and cultural context in which institutions form. In that case, he read the potential reception for the National Republican agenda poorly and failed to see the growing power of the ideology of the “common man,” so skillfully exploited by Jackson and his allies. But when Congressman Adams later confronted the dominant slave power in the House of Representatives, he knew exactly how to combat a powerful institutional barrier to his goals. Perhaps the most notorious of these was the “gag rule” of 1836, which—on entirely dubious constitutional grounds—allowed Congress to agree not to consider antislavery petitions. This bold measure contradicted a constitutional mandate that allowed citizens to submit specific grievances to Congress via petitions. To its architects, however, the gag rule was a way to conveniently dispose of an enormously divisive issue.

Rather than wither in the face of this questionable tactic, Adams insisted upon forcing his opponents to invoke the gag rule time and again, thereby repeatedly reminding the public that its representatives were not fulfilling their constitutional duties. Perhaps Adams lost in the short run, for few antislavery petitions found their way into the Congressional Record. But in the long run, Adams’s actions provided an invaluable boost to the abolitionist cause by eroding the House’s practice of ignoring the slavery issue. Through these sorts of parliamentary struggles, Adams tested the formal and informal power relationships that constitute the lifeblood of a core political institution. For the new institutionalists, Adams’s fight serves as yet another reminder of how institutions and their histories can offer fresh perspectives on the forces that have shaped the United States.

The author would like to thank Robin Einhorn, Ed Gray, Richard John, and Jeff Pasley for their patience and helpful comments on this essay.

Further Reading:

For a much more extensive and inclusive account of new institutionalism and the early American republic than space allows here, please consult the essays in Richard R. John, ed., Ruling Passions: Political Economy in Nineteenth-Century America (University Park, Pa., 2006), which originally appeared as a special edition of The Journal of Policy History 18:1 (2006). For a good brief overview of APD scholarship, see Karen Orren and Stephen Skowronek, The Search for American Political Development (New York, 2004) or Paul Pierson, Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis (Princeton, N.J., 2004). A recent forum in Polity 40:3 (July 2008), entitled “Politics, History, and the State of the State,” covers a wide range of new-institutionalist scholarship on the early American republic and beyond. Mark Wilson provides an excellent synthesis of antebellum institutional history in his recent essay entitled “Law and the American State, from the Revolution to the Civil War: Institutional Growth and Structural Change,” in Michael Grossberg and Christopher Tomlins, eds., The Cambridge History of Law in America, Volume II: The Long Nineteenth Century (1789-1920) (Cambridge; New York, 2008): 1-35.

Works cited in the essay as examples of the new institutionalism include: Colleen A. Dunlavy, Politics and Industrialization: Early Railroads in the United States and Prussia (Princeton, N.J., 1992); Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Cambridge, Mass., 1995); John Lauritz Larson, Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2001); Andrew M. Schocket, Founding Corporate Power in Early National Philadelphia (DeKalb, Ill., 2007); John Majewski, A House Dividing: Economic Development in Pennsylvania and Virginia, 1800-1860 (New York, 2000); Naomi R. Lamoreaux, Insider Lending: Banks, Personal Connections, and Economic Development in Industrial New England (New York, 1994); Edward J. Balleisen, Navigating Failure: Bankruptcy and Commercial Society in Antebellum America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2001); R. Daniel Wadhwani, “Citizen Savers: Family Economy, Financial Institutions, and Public Policy in the Northeastern United States,” Enterprise & Society 5 (December 2004): 617-24; Sharon Ann Murphy, “Securing Human Property: Slavery, Life Insurance, and Industrialization in the Upper South,” Journal of the Early Republic 25 (Winter 2005): 615-652; Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); Sean Patrick Adams, Old Dominion, Industrial Commonwealth: Coal, Politics, and Economy in Antebellum America (Baltimore, 2004); Robin L. Einhorn, American Taxation, American Slavery (Chicago, 2006); William J. Novak, The People’s Welfare: Law and Regulation in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1996).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Sean Patrick Adams is associate professor of history at the University of Florida and shares no relation (that he knows of) with John Quincy Adams. He is the author of Old Dominion, Industrial Commonwealth: Coal, Politics, and Economy in Antebellum America (2004) and is currently working on a study of domestic heating in nineteenth-century America and the history of an antebellum iron furnace community in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. Institutions, of course, figure prominently in both projects.