The Awful Truth

Has a historian solved the mystery of Charles Brockden Brown?

The terrorists not only murdered but also mutilated their victims. They brained infants and burned men alive in front of their wives. In response, some on our side also began to kill and soon convinced the government to declare war. Anyone killing a terrorist would receive a bounty from the state. Only a small subset of our community remained calm enough to wonder why the terrorists were angry. To the consternation of their compatriots, this subset arranged a conference, where the terrorists explained why they had turned to violence: twenty years earlier, at the behest of a family whose role in our government was all but dynastic, we had taken their land by fraud.

In 1737, an agent of the Penn family, proprietors of the Pennsylvania colony, took advantage of a contract’s ambiguous wording to seize twelve hundred square miles of land from the Delaware Indians. Alan Taylor’s recent history of colonial America calls the act “perhaps the most notorious land swindle in colonial history.” The Walking Purchase, as the swindle has come to be known, got its name from the way it was perpetrated. Pennsylvania officials convinced Delaware leaders to sign away a tract of land along the Delaware River that could be walked in thirty-six hours. The Indians seem to have expected the walk to be roughly twenty miles, but one of the colony’s walkers managed to go roughly three times that far, because officials had arranged to clear the path ahead of time. Two decades later, when the once friendly Delawares attacked white colonists during the French and Indian War, only the most pious Quakers in the colony had the presence of mind to ask why.

The independent scholar Peter Kafer believes that the Walking Purchase is the dark but true history behind one of the first Gothic novels ever written in America, Edgar Huntly, by Charles Brockden Brown. He sees references to the fraud in the 1799 novel’s geographic details and in its plot, which involves Delawares who have turned inexplicably violent. Once Kafer makes its case, it is hard to disagree. The incredible thing is that it took two centuries for Brown’s fiction to yield its secret.

I.

Charles Brockden Brown is the undisputed father of American horror. He imported Gothic novels into our literary tradition by writing and publishing four of them in 1798 and 1799. I remember when I first heard of him, as distinctly as I remember my first cigarette. A friend of mine called to tell me that he had just read a novel where one character spontaneously combusts, and another receives a vision from God telling him to kill his family. “You’d like it,” my friend said. “It’s crazy.” This was a compliment in our vocabulary. It described an artist who knew how to go to pieces, a feat we admired more or less the way that New Critics had once admired poets who knew how to put things artfully together. I took this friend’s advice about everything. He had told me to listen to Big Star and Yo La Tengo, and he had been right about them.

His suggestion proved fateful. I quit smoking years ago, but I became a Charles Brockden Brown geek irrevocably. I always feel as though I have to apologize for this. Not one but two chapters of my book concern him, and when nonscholar friends volunteer that they have started to read it, those are the chapters I warn them about. It may be more than you want to know, I say.

But it is not more than I want to know. Brown’s prose style is clumsy, and his plots are ill formed, but my curiosity about him has seemed at times to be insatiable. He provokes it much the way Melville does: his novels are thick with allusions to the events of his day–glancing allusions that make you wish you were as familiar with them as he is. Like Melville, he seems to have lived out the tragic myth of the American writer, the bold experimenter who flies too high and is punished by a breakdown of some kind–possibly psychological, almost certainly financial–which leads, in turn, to a dramatic shift in style. There is the lure of esoteric meaning. Is Melville suggesting that Ahab was a Gnostic? Is Brown suggesting that Carwin belonged to the Illuminati? Maybe if you read the novels one more time you will figure it out. And most enticingly, Brown, like Melville, gives the reader the impression that he is playing with masks. You are not sure which mask is hiding his true intention, or whether he has any true intentions at all. There must be a reason the tree is an elm. There must be a reason the summerhouse has twelve columns. If only you knew a little more . . .

In 1799, it was already conventional for a Gothic novel to have lurid and bloody episodes, a plot full of abrupt dislocations, and characters mysterious even to themselves. As Brown himself admitted, he merely updated the genre for the New World by replacing such European devices as “castles and chimeras” with American ones like “incidents of Indian hostility, and the perils of the western wilderness.” And in 1799, it was already understood that Gothic novels were written with mysteries because puzzling over them was one of the pleasures they offered. Whether by design or shoddy workmanship, Brown’s Gothic novels have a generous number of loose ends and ragged seams, and ever since Brown was added to the canon, sometime in the last couple of decades, scholars have taken up his puzzles with a vengeance. Recently he has been examined in light of Federalist-era aesthetic theory, eighteenth-century nosology and etiology, the significance of land in America’s national myth, Philadelphia’s German community, and a well-documented 1782 murder. But although the circles of interpretation around Brown have been widening steadily, he himself has been strangely neglected. Surprisingly few researchers have looked in archives for documentary evidence about his life. There is a Library of America edition of his novels, but there has never been an adequate biography.

There still is not one, exactly. Peter Kafer has chosen to write something less conventional, though just as exhaustively researched. Beneath each of Brown’s fictions, Kafer believes, lies an episode of history at odds with national myth. “Brown embellished, exaggerated, transposed, fantasized,” he writes. “But what he wrote was grounded in verifiable experience. And in memory.” Kafer aims to unearth these memories, and so he has written not a chronological narrative of Brown’s life but, fittingly, a series of detective stories.

II.

For his alternative American history, Brown drew on what Kafer calls an “underworld of tribal knowledge.” The tribe in question was the Pennsylvania Quakers.

According to a family history, the first Brown to convert to the Society of Friends was a farmer in Northamptonshire, England, in the middle of the seventeenth century. He was convinced by a traveling Quaker who began his testimony with the words, “O Earth! Earth! hear the word of the Lord.” Later the same man prophesied prosperity in America, and between 1677 and 1684, two of the farmer’s sons emigrated.

The Society of Friends was not the only new and unorthodox religion in late-seventeenth-century Pennsylvania. As Kafer explains, the colony was a hotbed of mystics and seekers. While living in Chichester in the 1690s, the two Brown brothers nearly fell out when one was tempted to join a new sect led by George Keith. Keith had been converted to the Quaker faith by the same man as their father but had then moved on to Kabbalism and a belief in reincarnation. Keith’s group was allied with the Brethren in America, which also contained ex-Quakers and was led by Henry Koster, another student of the Kabbalah. Koster, in turn, had previously belonged to the Hermits of the Wissahickon, a group of mostly German pietists led by a mystic named Johannes Kelpius, who had come to Pennsylvania by way of London. If the Brown brothers attended the 1696 yearly meeting of the Society of Friends in Burlington–and Kafer suspects they did–then they heard Henry Koster defiantly assert that his sect was true to the teachings of Jesus Christ and the Society of Friends was not. Most in the audience were annoyed rather than persuaded, and in the end the Brown brothers remained Quakers.

To any reader of Brown’s first novel, Wieland, these stories of eccentric schisms and self-taught seekers will sound familiar. The novel’s narrator and heroine, Clara Wieland, explains that her family was German in origin. Like Johannes Kelpius, her father lived in London before coming to America. His more or less accidental reading of the words “Seek and ye shall find” in a history of the Camisards, a French Protestant sect, led to his religious awakening, which took the form of sedulous, idiosyncratic study of this Camisard history and the Bible. He emigrated to Pennsylvania because he came to believe that he had a religious duty to convert the American Indians, but he did not succeed as a proselyte. In his retirement, he built a temple where he worshiped alone, guided by his strict construction of the text of Matthew 6:6 (“But when you pray, go into your room and shut the door”). As Clara explains, “He rigidly interpreted that precept which enjoins us, when we worship, to retire into solitude, and shut out every species of society.” His retreat thus paralleled that of the Hermits of the Wissahickon, who recorded that they felt called “to live apart from the vices and temptations of the world, and to be prepared for some immediate and strange revelations which could not be communicated amid scenes of worldly life, strife and dissipation, but would be imparted in the silence and solitude of the wilderness.”

Here Kafer does some sleuthing that will take your breath away if you are a Charles Brockden Brown geek. In Brown’s novel, Father Wieland’s private temple is said to resemble a summerhouse. It is twelve feet in diameter, “edged by twelve Tuscan columns, and covered by an undulating dome,” and it sits on a rock beside a sixty-foot cliff overlooking the Schuylkill River, five miles outside Philadelphia. Kafer has discovered that in the nonfiction world, this location “turns out to be where the Schuykill meets the Wissahickon, and is where the Kelpius community lived.” Kelpius’s Hermits of the Wissahickon built a tabernacle on the site, with an architectural plan determined by Rosicrucian numerology. In the late eighteenth century, Brown could have toured the ruins. The portion still standing then was circular. Kafer prints a photograph of the riverside landscape as it appeared in 1999, eerily similar to Brown’s description of Father Wieland’s temple grounds. In a footnote, Kafer observes that Brown could have walked to the spot from the country home of a lawyer he studied with and that the adjacent property belonged to the family of one of Brown’s closest friends.

To a Brown fan, this is heady. It is equivalent to telling a Melville fan that the Pequod has been located and raised from the deep. Wieland’s temple is crucial to Brown’s first novel. It is where “a cloud impregnated with light” seized on Clara’s father and scorched him, in an episode of either spontaneous combustion or divine punishment. And it is where, years later, Clara’s brother bantered with his friends about Cicero, until he too saw a mysterious light, on the night he began to hear the voices that would drive him mad.

III.

In 1702 the two sons of the first Quaker Brown moved to Nottingham, Pennsylvania, near the Maryland border, where the land was fertile and the corruption of the city safely distant. In Nottingham, many of the Browns would become ministers, which was not a formal office among Quakers, but indicated a person who heard with some regularity the inner voice of truth and felt called to share it with others.

The following generation of Browns married into another devout family, the Churchmans, and by the middle of the eighteenth century, they were highly respected in Nottingham. Into this pious, rural community Elijah Brown, the novelist’s father, was born in 1740. At the time, the most celebrated person in the family was Elijah’s uncle, the minister John Churchman. So great was Churchman’s moral prestige that in 1748, when the Pennsylvania Assembly was debating whether to pay for a warship, they listened at length to his opinion even though he held no governmental office and spoke merely as “a country man . . . having something to communicate.” He told them, of course, that a colony founded on Quaker principles should not arm itself.

During the French and Indian War, Churchman was one of the Quakers who tried to restore peace with the Delawares, whom the Walking Purchase had embittered. The crisis so engaged him that it brought on a vision. Riding to a treaty conference in 1756, he saw a light as bright as a rainbow, in “a human form about seven feet high,” which he took to be an angel. (Shades of Wieland.) At a November 1756 conference, Churchman heard the leader of the Delawares declare that “this very Ground that is under me . . . was my Land and Inheritance, and is taken from me by Fraud.” According to Kafer, the money for the conference came in part from another of Charles Brockden Brown’s great-uncles and from the father of one of the novelist’s closest friends, both of whom probably also attended. In other words, to Charles Brockden Brown the Walking Purchase was not just an important piece of recent history but one that had touched his family particularly.

The fraud had originally come about this way. In 1737, to secure the rights to the southeast portion of Pennsylvania and to raise money for one of William Penn’s sons, Chief Justice James Logan pressured the Delawares to confirm what he said was a 1686 deed of land already sold to William Penn. In fact it was either the rough draft of a deed never executed or an outright forgery. The Delawares signed it nonetheless, perhaps because it seemed to involve land that had already been given to the Penn family by other treaties. It specified a tract extending north by northwest from present-day Wrightstown as far as could be walked in “a day and a half.” The Delawares were led to believe that this ambiguously worded distance was about twenty miles. That would have brought the whites not much further north than Tohickon Creek, which runs through present-day Point Pleasant and which approximated the Delawares’ sense of their southern boundary anyway.

James Logan intended to stretch the tract much farther, however. After the treaty was signed and before the land was surveyed, Logan had a path through it cleared. During the official “day and a half” that the land was measured out, two of the three men hired by Logan as “walkers” quit from exhaustion, but a third managed to go sixty-four miles before collapsing–some forty-seven miles beyond Tohickon Creek. When the Delawares protested that they had been cheated, Logan made a military alliance with the Iroquois, who drove the Delawares out.

IV.

Brown’s last novel, Edgar Huntly, is not, at first glance, about land fraud. Instead it seems to concern a young man in mourning who lives in the town of Solebury, Pennsylvania.

Edgar Huntly is distraught by the recent murder of a virtuous and wealthy friend. One night he visits the elm where his dying friend was discovered, and by the light of the moon he sees a naked sleepwalker digging and weeping. Naturally he suspects the digger of murder and decides to investigate. After watching a second night, he follows the sleepwalker into a wilderness area called Norwalk, described as “rugged, picturesque and wild,” where he loses him. Confronted by day, the sleepwalker confesses, but not to the crime of which Huntly suspects him. Then the man vanishes. In pursuit, Huntly returns to Norwalk, where he again sights his suspect and again loses him. Frustrated and agitated, he dreams of the “inquietude and anger” of his murdered friend. One night soon after, he goes to bed in Solebury and wakes up in a cave in Norwalk. He too has become a sleepwalker, and he has woken up in the middle of a bitter, violent war with the Indians. He picks up a tomahawk and begins to kill.

In suggesting a link between the Walking Purchase and Edgar Huntly, Kafer is following up a hint dropped by the amateur Brown scholar Daniel Edwards Kennedy, which was first mentioned in print by Sydney J. Krause in his historical note to the Kent State edition of the novel published in 1984. Kafer makes a compelling case. Some of the clues in the novel are explicit. When Huntly is surrounded by hostile Indians, he admits to the reader that “a long course of injuries and encroachments had lately exasperated the Indian tribes.” The bloodiest scenes in the book occur near the hut of Old Deb, an Indian who is said to have remained in the area after the rest of her tribe had departed and to have “originally belonged to the tribe of Delawares or Lennilennapee.”

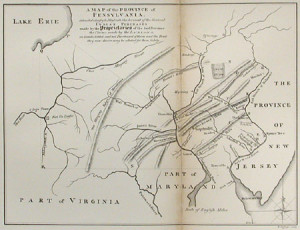

But it is geography that clinches it. Solebury, the hometown of Edgar Huntly, lies about five miles southeast of Tohickon Creek, well within the region that William Penn had legally purchased long before the 1737 fraud. (When I consulted a modern-day map, DeLorme’s Pennsylvania Atlas & Gazetteer, I came up with mileage slightly different from Kafer’s. Tohickon Creek bends and twists dramatically, which may account for the discrepancy.) Although Brown never lived in Solebury himself, he may have felt some kinship to it; Kafer reports that among the earliest landowners in Solebury were the family of Charles Brockden Brown’s mother and the father of the Charles Brockden for whom he was named. Huntly leaves Solebury, however, to pursue his murder suspect into Norwalk, where most of the action takes place. Brown consistently locates Norwalk to the north of Solebury, but he gives conflicting descriptions of its extent. He first describes it as “a space, somewhat circular, about six miles in diameter.” But later he writes, “Norwalk is the termination of a sterile and narrow tract, which begins in the Indian country. It forms a sort of rugged and rocky vein, and continues upwards of fifty miles.”

Norwalk is, therefore, a wilderness that either reaches six miles north of Solebury, which would put its northern edge roughly at Tohickon Creek, or reaches fifty miles north of Solebury, which would put it some forty-five miles beyond the creek. Sound familiar? As Kafer writes, succinctly, “‘Norwalk.’ North Walk.” On their way north in 1737, James Logan’s walkers would have passed by not only Solebury but every setting in Edgar Huntly.

V.

The Quakers’ exposure of the Walking Purchase fraud altered nothing for the Delawares. The treaty remained in force. Back in Nottingham in December 1756, a dismayed John Churchman told his fellow Quakers that he heard a voice saying, “I will bow the inhabitants of the earth, and particularly of this land, and I will make them fear and reverence me, either in mercy or in judgment.” The gloom of Churchman’s ministry must have told on his nephew, because two months later, Elijah Brown left small-town Nottingham for Philadelphia, where he hoped to become a merchant. Exactly nine months after that, Kafer reports, “his father and stepmother had another son; and at this point they did a most peculiar thing. They named their new son Elijah–as if the other Elijah, a healthy seventeen-year-old . . . were dead.”

It was not easy to move from pious Nottingham to worldly Philadelphia, and Elijah Brown never really succeeded at the transition. The one asset Nottingham might have been expected to provide, a sturdy moral compass, seems to have gone missing in his case. Kafer thinks the novelist may have been painting a portrait of his father in his third novel, Arthur Mervyn. The hero claims to be a nice boy from the country who has fallen in with bad company through no fault of his own, but he may, in fact, be as unscrupulous as Welbeck, the evil mastermind who is supposed to have misled him.

Some such ambiguity beclouded Elijah. He copied out extracts from the works of the atheist anarchist William Godwin and the deist feminist Mary Wollstonecraft in his commonplace books, which survive in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and so scholars have long known that his intellectual interests were not those of an altogether orthodox Quaker. Kafer has discovered that his career was not quite orthodox, either. His 1761 marriage to Mary Armitt brought him access to the good credit of her brother-in-law, Richard Waln, and he soon set himself up as a merchant. But in 1768 his fellow Quakers disowned him for failing to pay his debts and for misleading creditors about the extent of them, and he was never restored to their good graces. In the spring of 1770, in a desperate attempt to repay his brother-in-law, he went to the West Indies and smuggled tea. “Devious deliveries to one ‘Richd Somers’ at an out-of-the-way harbor in New Jersey would seem a long, long way from the Quaker principles of John Churchman and Nottingham,” Kafer comments. Elijah gave up on his ambition to be a merchant. Waln’s subsequent loans to his brother-in-law were acts of charity rather than business, and Elijah never repaid them. He continued to sell as a retailer until July 1784, when he was jailed for debt. The debt was of a “conciderable amount,” according to Waln, and it ended Elijah’s shopkeeping. After 1784 he worked as a conveyancer, copying legal documents and writing out the paperwork for real-estate transactions.

Charles Brockden Brown was born into this struggling family in January 1771. In Wieland, when Clara recalls the mysterious light and explosion that burned her father in his temple, she notes,”I was at this time a child of six years of age. The impressions that were then made upon me, can never be effaced.” Kafer notes that the novelist was six years old during the most frightening of his father’s travails, which came during the Revolutionary War. To a child, its sights and sounds may have been just as inexplicable and traumatic.

Quakers were sidelined from the Revolution by their pacifism and their refusal to swear oaths. It was not a sudden displacement, however, but the culmination of a decades-long process. The Quakers’ peaceable attitude toward the Indians had long ago wrong-footed them not only with the lordly Penn family and its allies but also with many of the common people who settled on the Pennsylvania frontier. In 1763 and 1764 a group of frontiersmen known as the Paxton Boys rioted. They murdered a score of Indians–in his Cultural History of the American Revolution (New York, 1976), the scholar Kenneth Silverman likened the massacre’s impact to My Lai’s–and then marched to Philadelphia, where they threatened to hang the colony’s most prominent Quaker politician.

The Paxton Boys, as Quakers noted at the time, were “principally of Irish extraction.” That is, they were Scots-Irish Presbyterians, an ethnic group that was immigrating to Pennsylvania in droves. Quaker politicians retaliated with what historian Patricia U. Bonomi has called “a virulent anti-Presbyterian campaign.” In the long term, the campaign did not serve Quakers well. The Paxton Boys were the sort of people to whom power flowed, in the form of committees and militias, when the Revolution came. When John Adams compiled a list of potential traitors in Philadelphia in 1777, he probably got his information from people like them; everyone on his list was a Quaker. Many of those he named had helped to fund the 1756 conference with the Delawares where the Walking Purchase fraud was brought out–an overlap that, in Kafer’s opinion, “is not a historical coincidence.”

Kafer believes that by the time of the Revolution, the Quakers, although usually too couth to spell it out, understood Scots-Irish Presbyterians as their tribal enemies, more or less. In fact, when the British army occupied Philadelphia from September 26, 1777, to June 18, 1778, some Quakers appreciated their presence. “We may expect some great suffering when the Englis Americans again get possession,” one Quaker confided to her diary. (Not all Quakers dreaded American troops, however. While waiting out the occupation in rural Gwynedd, Sarah Wister flirted with American soldiers gaily; when she reported in her diary that the British had abandoned the capital, she brought out her best faux French and called the news “charmonte.”)

After Adams’s 1777 list of traitors was expanded and refined, the people on it were rounded up. Quakers privately recorded the names of the men who made the arrests. Almost all were Scots-Irish. For example, at noon on September 5, 1777, Elijah Brown was arrested by James Loughead and James Kerr. (I can vouch for Kerr’s Scots-Irish genealogy, because I happen to be descended from him.) On September 11, 1777, Elijah Brown, sixteen other Quakers, and three outright Tories were driven out of Philadelphia in wagons. There had been no trials or hearings. When the prisoners applied for writs of habeas corpus, the Pennsylvania Assembly passed an act retroactively suspending the right to habeas corpus in their cases only. They were taken to Winchester, Virginia, where they were overcharged for their room and board. Over the winter, two Tories ran away and two Quakers died. Four of the exiles’ wives appealed personally to George Washington at Valley Forge, and at the end of April 1778, the exiles were finally allowed to go home.

The Revolution did not, therefore, mean to Charles Brockden Brown what it may have meant to other boys who were then six years old. It took away his father. In Edgar Huntly, the narrator, just before he begins to kill Indians, explains, “Most men are haunted by some species of terror or antipathy, which they are, for the most part, able to trace to some incident which befell them in their early years.” Huntly claims that he is haunted by the slaughter of his parents by Indians. But as Kafer points out, from the perspective of the Brown family, “the native Indians weren’t the ‘savages.’ The Revolutionaries were.” The Indians in the novel seem to be standing in for the Scots-Irish Presbyterians who were, in real life, the deadly enemies of both Indians and Quakers. Kafer finds a further clue in the high number of Brown’s villains who are “Irish,” from Jackey Cooke, the wife-beater in Brown’s earliest attempt at fiction, to the sleepdigger of Edgar Huntly’s opening scenes, who was born to peasants living “in the county of Armagh.”

In his novels, the son remembered the violence that had harmed his family when he was a child–violence that the rest of America celebrated every July 4 with cannons and fireworks. He did not take up his father’s quarrels, however, or his religion’s. If Arthur Mervyn, for example, is a portrait of Elijah, it expresses a deep ambivalence. It is a serious betrayal of Quaker ethics for Edgar Huntly to kill Indians. And it is perverse of Brown to have signaled the onset of madness in Clara Wieland’s brother with a vision of light like that seen by John Churchman in 1757.

Kafer may have solved these mysteries, too. Charles may not have been able to represent his father as a hero because it was not the case. It turns out that Elijah was not exiled on account of his Quaker principles. He was arrested because even though the Revolutionary authorities had fixed the price of flour and were regulating its sale, he sold it, illegally, on the open market. And after they warned him not to, he continued selling it. He was, in other words, a war profiteer–though a very unskilled one, unable to survive his exile without borrowing even more money from the brother-in-law who had once sent him smuggling.

Standing up for Quaker ideals would not have avenged Charles Brockden Brown’s father, and standing up for Revolutionary ideals would have betrayed him. Such was the genealogy of a new kind of American writing, which gave voice to confusion and terror.

Further Reading:

No Brown aficionado can afford to be without Peter Kafer’s Charles Brockden Brown’s Revolution and the Birth of American Gothic, published in 2004 by the University of Pennsylvania Press. Some of Kafer’s discoveries were revealed in two earlier articles: “Charles Brockden Brown and Revolutionary Philadelphia: An Imagination in Context,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography 116 (October 1972): 467-98, and “Charles Brockden Brown and the Pleasures of ‘Unsanctified Imagination,’ 1787-1793,” William & Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 57 (July 2000): 543-68.

Online, the Pennsylvania State Archives offers a transcription and a digital photograph of the Walking Purchase Treaty, and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission reprints a 1972 essay on the fraud by William A. Hunter. The fraud is also discussed in Anthony F. C. Wallace’s King of the Delawares: Teedyuscung, 1700-1763 (Philadelphia 1949; rpt. Syracuse, 1990) and in Appendix B of Francis Jennings’s The Ambiguous Iroquois Empire: The Covenant Chain Confederation of Indian tribes with English Colonies from its Beginnings to the Lancaster Treaty of 1744 (New York, 1984).

The authoritative text of Brown’s novels is the Bicentennial Edition, published by Kent State University between 1977 and 1987 and overseen by Sydney J. Krause and S. W. Reid. The historical essays in each volume are in many ways unsurpassed, and Krause’s annotations for Ormond offer an excellent opportunity to those who wish to dive down the rabbit hole and into Brown’s idiosyncratic intellectual world. Penguin, the Modern Library, and the Broadview Press publish paperbacks of several Brown novels, and the Library of America sells a volume containing three of them.

Brown’s nonfiction is harder to find, but Mark L. Kamrath, Fritz Fleischmann, and Wil Verhoeven are directing a supplementary edition of Brown’s reviews, essays, short fiction, letters, and poetry, to be published electronically and in six bound volumes. Scholarship on Brown has exploded in the last few years, and Bryan Waterman, a leading practitioner, offers an insightful overview of the field in “Charles Brockden Brown, Revised and Expanded,” Early American Literature 40 (2005): 173-91.

This article originally appeared in issue 5.4 (July, 2005).

Caleb Crain is the author of American Sympathy: Men, Friendship, and Literature in the New Nation (New Haven, 2001). He is at work on a history of the 1851 divorce of the theatrical couple Edwin and Catharine Forrest.