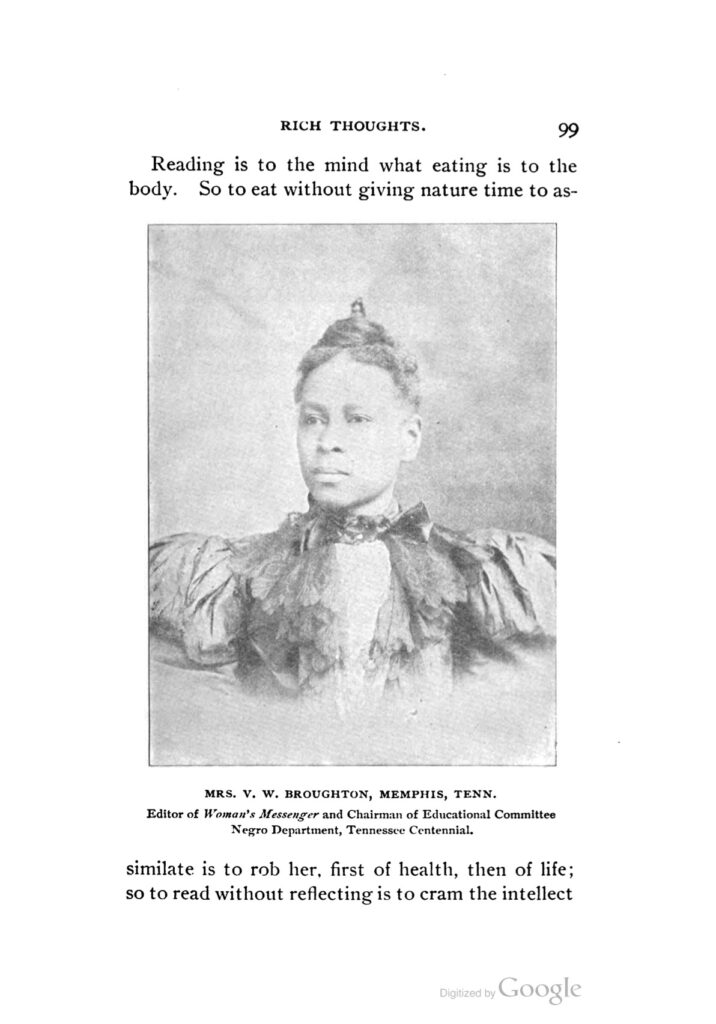

The Black Christian Womanhood of Virginia W. Broughton

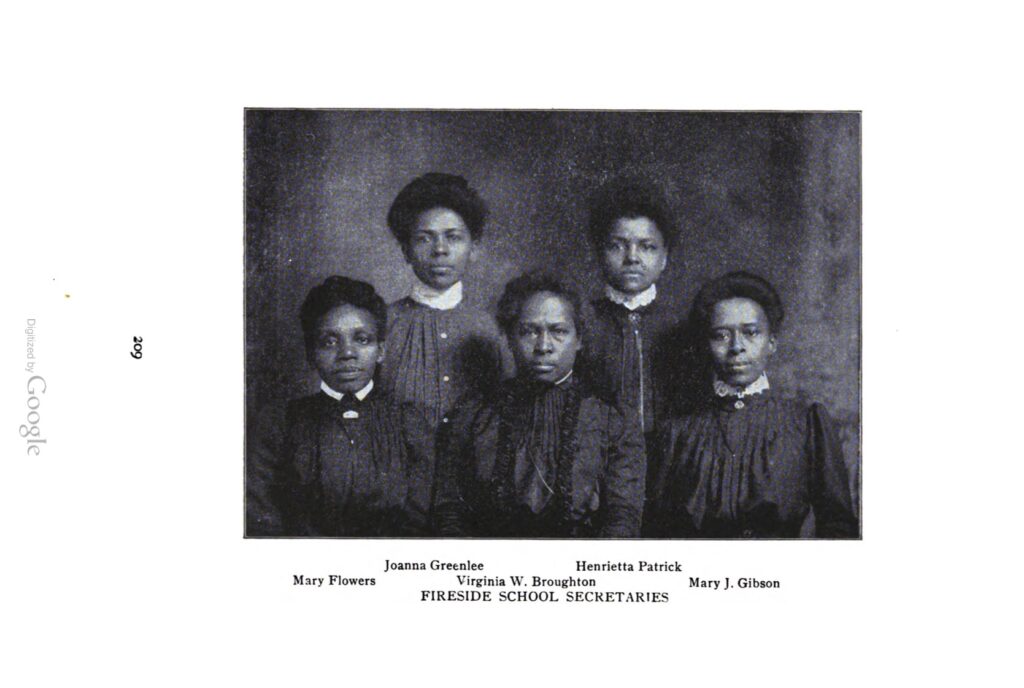

In this beginning of organized missionary effort[s] among Negro women in Tennessee the following fundamental principles were emphasized as necessary to our Christian development as women: First, simplicity, cleanliness and neatness in dress and in our home furnishings. Second, wholesome, well prepared food. Third, the temperate use of all good things and total abstinence from poisons, tobacco and liquors being specified. Fourth, the education of heart, head and hand. Fifth, above all things, loyalty to Christ as we should be taught of Him through the daily prayerful study of His word.

—Broughton’s autobiography, Twenty-Years’ Experience of a Missionary (12–13).

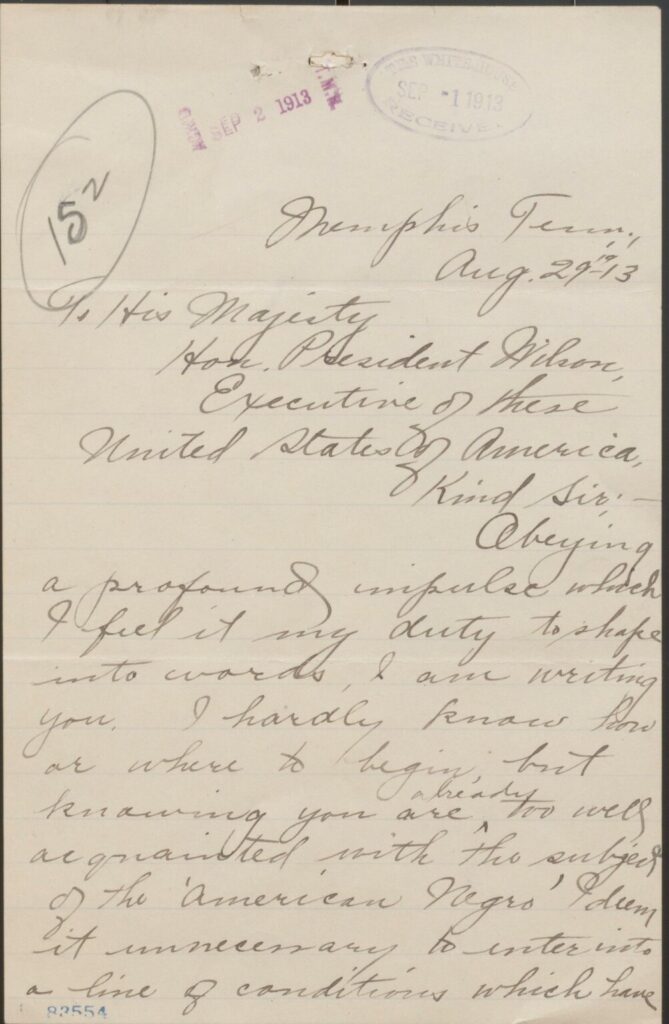

Though Virginia W. Broughton (1856–1934) is commonly recognized as an educator, missionary, writer, and feminist dedicated to the uplift of the Black race during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow Era, she was also a theologian who crafted an empowered and independent vision of Black womanhood. This article explores how Broughton presented a model of Black Christian womanhood that developed women’s roles not only in the home but also in the church and in educational settings. In particular, it shows how this Holiness Baptist woman and Black American intellectual employed Spirit-centered language, biblical typology, and oppositional rhetoric in that work.

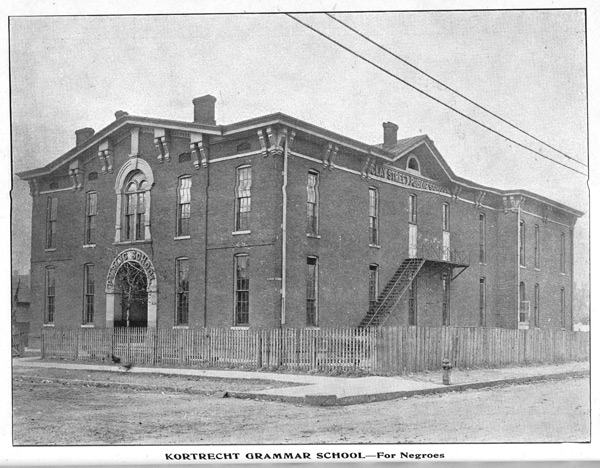

She was first influenced by her father, Nelson Walker, an educated freedman —a rarity in the early 1860s when roughly 95 percent of Southern Black individuals could not read and write. Thanks to her father’s support, Broughton had access to early educational opportunities, eventually becoming the first Black woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in the South in 1875. She later worked at public schools in Memphis, rising to the position of assistant principal at the Kortrecht Grammar School, Memphis’s most advanced public school for African Americans.