The Capitalist Portrait

Collecting at the New York Chamber of Commerce

Though the collection of the New York Chamber of Commerce is now dispersed and the institution has faded into history, the extravagant Great Hall, located in the chamber’s headquarters on Liberty Street, was once the Olympus of American business (fig. 1). Looking at the thick installation of paintings hung in tiers on paneled walls, a viewer might simply isolate the portrait of an honored individual. But the overarching purpose of the Great Hall was instead to project onto the viewer the meta-impression of a cohesive family of professional fathers and brothers, the overall architecture of the display taking on the distinct look of a kinship, with all its suggestions of affinity, loyalty, obligation, power, and dynastic propagation. Matthew Pratt’s large “ancestral” portrait of Cadwallader Colden, the eighteenth-century New York agent for the chamber’s royal charter, always occupied the central position on the east wall, below which, on a dais, was positioned the chair and podium of the chamber’s current president. Flanking Colden on both sides were smaller portraits stacked in horizontal rows. Whatever the particular arrangement and density of the flanking pictures, which changed from time to time, they always had the look of being the “descendants” of Colden, giving the Great Hall a sense of both ancestry and succession.

Founded in 1768 and chartered by King George III in 1770, the chamber came to serve the small-scale antebellum merchants of the city. It did not begin to collect portraits, however, until after the Civil War, when powerful individuals dominated the economic landscape of New York. Eventually numbering more than three hundred (both commissioned and donated), most of them were installed in the Great Hall, a ninety-by-sixty-foot paneled room with a thirty-foot ceiling, set into James Barnes Baker’s beaux-arts building at 65 Liberty Street. The chamber’s collecting initiative coincided with the new bourgeois effort of other occupations that were also interested in their public reputations and wishing to use portraiture to project or stabilize a coherent new image. Doctors, for example, used portraiture to fashion themselves into men of letters or science as part of an effort to overcome the common stereotype of physicians as experimenters or butchers. Likewise, the chamber tried to rebut the negative stereotype of “robber baron” that dogged some businessmen by filling its spaces with images of thoughtful, polite, conventional, even noble men. Their inoffensive collective identity served the conformist—rather than transgressive—status aspirations of an ascendant professional group.

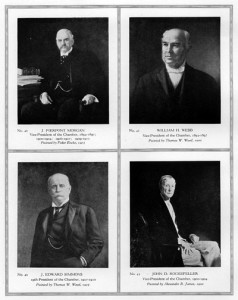

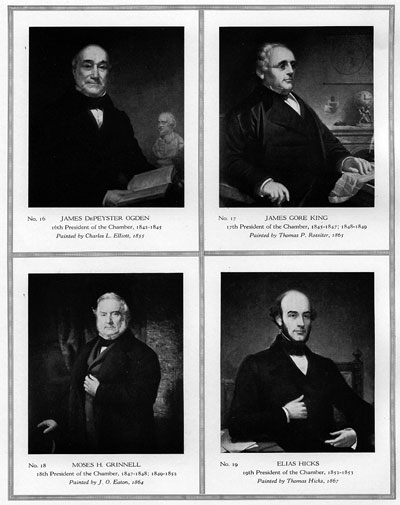

For the Great Hall to amount to an ersatz business family, the perception of individual identities had to yield to the visual network that conveyed the fiction of a unified fraternal community, its members positioned shoulder to shoulder. Though the portraits of merchants, capitalists, and financiers had been collected by or donated to the chamber over many years and painted by a variety of artists (notably Eastman Johnson and Daniel Huntington), most of the signs of individuation had been repressed and replaced by narrow typological templates. (One hundred and eighty of the pictures that are now in the New York State Library can be viewed digitally). Not surprisingly, then, most of the portraits downplay the sitter’s particular triumphs. Though there is the anomalous sight of merchant Peletiah Perit sitting between a stack of money and a view of a freighter loading up in New York harbor or that of railroad entrepreneur James Gore King (fig. 2) beside a clock held up by Atlas, over which is suspended a map of the world, the typology of mastery and power is uncommon in the chamber’s collection. Instead, the pictures concentrate, for the most part, on confidence, grace, intelligence, character, respectability, sincerity, some minor business activity, and rarely any personal life. They de-emphasize the specific attributes and behaviors associated with running a business or making money or even conspicuously giving it away and instead encourage viewers to focus on the generalized look of high character. These men are to be understood above all as gentlemen. For example, both banker Samuel Babcock and merchant Josiah Orne Low sit face forward and remove spectacles with their right hands in order to address the viewer with solemn earnestness. New York Stock Exchange president J. Edward Simmons (fig. 3), leather trader Jackson S. Schultz, real estate magnate Amos Eno, and Equitable president Henry B. Hyde stand like classical orators. Some, such as railroad financier John S. Kennedy and Equitable president Thomas I. Parkinson, handle letters and papers. A significant number, such as James DePeyster Odgen (fig. 2), hold or are engrossed in books or prints. And the great majority of pictures show even less. Mostly bust-length portraits (approximately 140 of them), they depict men emotionally uninflected and with few or no objects, even when the person portrayed was known to have led a high-achieving or flamboyant life.

In the Great Hall, there is such a sense of sameness in the men’s appearances that it does not take much effort to see that personality has been deliberately tamed for the sake of assembling an artificial society, a seamless superstructure open to being expanded, contracted, and reconfigured by house fiat. It was an aesthetic system that muted idiosyncrasy, as if all diversity could be checked like an overcoat at the chamber’s front doors.

Of course the impression that these businessmen were kin was, as Georg Simmel pointed out in his 1922 essay “The Web of Group-Affiliations,” a fiction. As a business organization, the chamber functioned well because disconnected individuals from “heterogeneous groups” (rural, urban, Protestant, Jewish, etc.) became newly “related” by a “similarity of talents, inclinations, activities, and so on.” These men, who might have been strangers or foes outside the affiliation, willingly and temporarily repress cultural differences in order to form “a group whose cohesion was based on purpose.” Yet for all the solidarity pictured in the Great Hall, few of these men would have actually wished to mingle or to export their in-chamber alliances to what Simmel called “every nook and cranny” of their “natural relationships.” Their real-life affiliation was collapsible, as men only occasionally assembled at the chamber for a specific purpose and then disassembled, moving back to other, more constant and entrenched social structures. Some of these men, especially those owning railroads, were actually in mortal conflict with one another, vying for markets, stocks, shipping routes, track rights, and patents. Commodore Vanderbilt, for example, considered his railroad rival and fellow chamber member James J. Hill to be a dangerous threat to his New York Central empire. Meanwhile, Jacob Schiff battled against chamber colleague J. Pierpont Morgan (fig. 3) in advancing Edward H. Harriman’s hostile bid to take over Hill’s Northern Pacific Railroad.

The solidarity pictured in the Great Hall was ultimately, then, a rhetorical expression of the institutional aims of the chamber. All identities, however complex and conflicted they might have been on the street, now flatten out, so as to “make it appear to others as a unified group.” Though the pictures in the gallery promise professional congruity and mutual order, the real-life logic of competitive individualism modified the possible pleasures of fraternal exchange. This is to say, the competitiveness of businessmen with each other was temporarily interrupted on the walls of the chamber for the sake of a common purpose and replaced by the aggregate image of a placid network, a family tree, a professional genealogy. If a pan-business brotherhood existed as an ideal or goal of the New York Chamber of Commerce, it was mostly manifested in the pictorial unity on the chamber’s walls and not necessarily on Wall Street. In the headquarters of American capitalism, of all places, the discourse of professional and personal rivalry, in which many of the businessmen reveled, was converted into the quiet visual economy of prestige and honor. However individualistic or idiosyncratic a Morgan or a Carnegie might have been, in the realm of the gallery their images conform to and share in the official visual norms of the chamber group, which in turn provides them with a share of the institution’s collective symbolic value.

Further Reading:

For an overview the chamber’s collecting, see George Wilson, Portrait Gallery of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York (New York, 1890). Many of the pictures can be viewed at the NYS Website. On the chamber in the city, see David Hammack, Power and Society: Greater New York at the Turn of the Century (New York, 1987). The negative image of the American businessman is thoroughly elaborated in Louis Galambos, The Public Image of Big Business in America, 1880-1940 (Baltimore, 1975); in Sigmund Diamond, The Reputation of the American Businessman (Cambridge, Mass., 1955); and in Matthew Josephson, The Robber Barons: The Great American Capitalists, 1861-1901 (New York, 1934). On the logic of collecting portraits of men in occupations, see Ludmilla Jordanova, Defining Features: Scientific and Medical Portraits, 1660-2000 (London, 2000) and her “Medical Men, 1780-1820,” in Joanna Woodall, ed., Portraiture: Facing the Subject (Manchester, UK, 1997): 101-15. Also see R. Burgess, Portraits of Doctors and Scientists in the Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine (London, 1973). On masculinity and fraternal action, see Dana D. Nelson, National Manhood: Capitalist Citizenship and the Imagined Fraternity of White Men (Durham, N.C., 1998). Simmel’s essay is published in Conflict: The Web of Group Affiliations (1922; reprint, Glencoe, Ill., 1955). For an analysis of the social structure of fraternal organizations, see Mary Douglas, In the Active Voice (London, 1982): 183-254; David Knoke and James R. Wood, Organized for Action: Commitment in Voluntary Associations (New Brunswick, N.J., 1981); and Eric J. Hobsbawm, “Fraternity,” New Society, 16:4 (27 November 1975): 470-73.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.2 (January, 2007).

Paul Staiti is professor of art history at Mount Holyoke College.