The Colored Conventions Movement in Print and Beyond

The minutes of Colored Conventions constitute one of the most important bodies of primary sources in African American history. The Colored Conventions Project website has brought together a large number of these documents for the first time ever. The necessary work of locating, scanning, uploading, cataloging, and transcribing builds upon the complex print history of the movement. This article offers an overview of the ways in which convention proceedings came into print in the nineteenth century, with the ultimate goal of demonstrating why the work of the Colored Conventions Project is vitally important for historians and for the rest of us.

The Importance of Print to the Movement

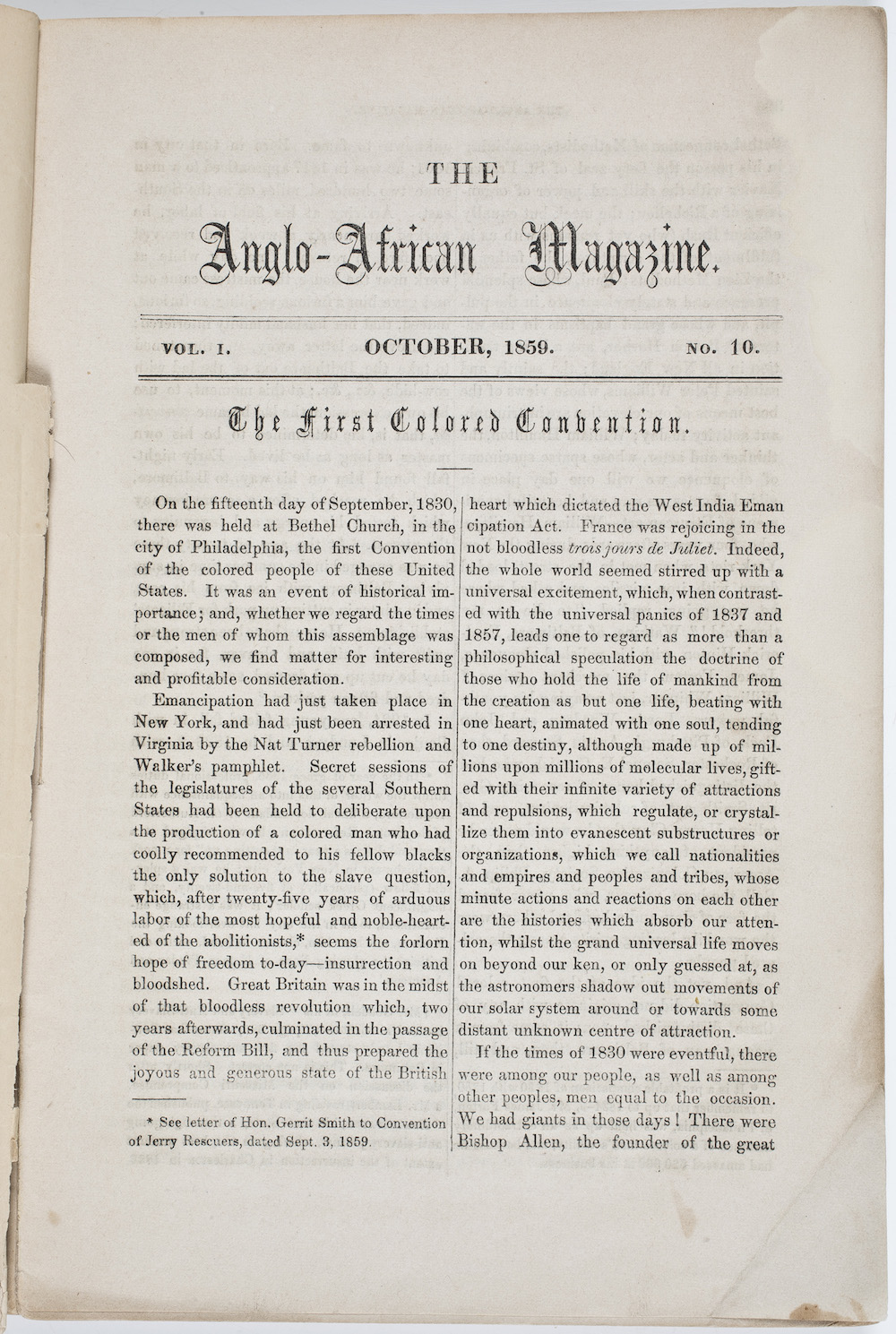

A resolution from the 1855 Colored Men’s State Convention in Troy, New York, proclaims, “This Convention strongly recommend(s) to the colored citizens to withhold their support directly and indirectly from all public journals that make it a point to misrepresent us as a people and the world but to use all means in their power to aid on the circulating of such papers as are ready and willing to do us justice.” The last part of this quote points to the well-known technological innovations that multiplied the production of newspapers and ephemeral documents in the nineteenth century. Scholars have shown how African Americans took full advantage of this democratizing trend for their own purposes. The Colored Conventions movement is an important example of this development. However, this fascinating quote also lays bare a surprising counter-strategy, involving a withdrawal from or refusal of certain kinds of print. The published record of the Colored Conventions movement unfolded in a violently contentious space of representation where the stakes were quite high. Print was to be used to further the movement, but it needed to be used in the proper fashion.

Derrick R. Spires writes that the conventions “began and ended in print, producing and circulating documents at each juncture in a way that kept their civic claims constantly in the public eye.” Print technologies offered a means of preparing the public for the debates and decisions that would take place at conventions, and for disseminating and commenting on those actions after the fact. Delegates knew that influencing Black and white public opinion was essential to the success of their political project. As weapons against racial oppression, the words of conventioneers were meant to be “heard” far beyond the walls in which they were pronounced. The print medium made this happen. Today, the Colored Conventions Project is using digital technologies to carry those voices even further. Individuals around the world are accessing the texts of convention minutes. The result is a growing understanding of the true importance of this massive movement.

Circumstances of Printing

With regard to the question of print, convention meetings were exercises in Black organizational autonomy. Printing committees were established alongside executive committees, business committees, and others. Delegates approved plans for the printing and distribution of hundreds or thousands of copies of the proceedings, and decided on the means of funding. In some cases, the title pages of the resulting pamphlets reveal the names of the printers involved. Printed copies of minutes were often given to attendees, who were expected to distribute or sell them, thus helping support the movement financially.

An exhibition on coloredconventions.org features interactive maps offering information about how national conventions planned for the printing of proceedings (“The Print Life of Colored Conventions Proceedings, 1830-1865 “). Drawing this information out of the minutes and placing it within maps allows viewers to easily absorb material that is spread throughout the minutes, while also providing a visual sense of the important regional dimension of the movement.

One section of the exhibit quotes plans to publish 1,000 copies of an address that had been delivered at the 1843 Buffalo, New York, convention. The speech in question was Henry Highland Garnet’s famous address to the slaves, which Sarah Patterson has discussed in an earlier essay. Frederick Douglass led the opposition to the adoption of Garnet’s speech, which invoked violent resistance as a path to freedom for enslaved Blacks. Based on another passage from the minutes, the exhibit also reveals that both Garnet and Douglass were named to the committee that was to oversee the publication of convention proceedings. The fact that both men sat on this committee suggests cooperation that cut across the lines of a disagreement that is the defining feature of the 1843 convention. However one is to interpret such details, their presence underlies the importance of the minutes as historical sources.

Newspapers

Before a convention took place, the publication of newspaper announcements (“calls”) was a necessary act of publicity that set the tone for the convention to come. Sarah Patterson’s essay explains the events surrounding the call that preceded the 1843 National Convention. Ten years later, the call for the 1853 Colored National Convention decried the recent passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, evoked other examples of discrimination, and announced the idea of a National Council, a permanent organization devoted to civil equality for Blacks. Championed by Douglass, this last idea was a direct response to the growing emigration movement, which Douglass opposed. The first significant document of the published proceedings of the 1853 convention elaborates on the topics announced in the call. In a lengthy address, Douglass again denounces the Fugitive Slave Act, calls for full citizenship rights for men of color, and gives details for the establishment of the National Council of the Colored People, which was envisioned as an expression of the democratic ideals that underpinned Douglass’s entire speech: the council was to be composed of free Blacks elected from each state, this at a time when the right to vote was non-existent for Blacks living in many of those states. The call had been used to announce the central feature of the coming convention.

In many instances newspapers published daily synopses of convention activities and reprinted the minutes afterward. Publications such as The Colored American, The Liberator, The National Anti-Slavery Standard, The Aliened American, The North Star, and The New Orleans Tribune are the only known sources for certain sets of proceedings. Although white-owned abolitionist periodicals such as The Liberator published minutes, many conventioneers aimed for autonomy of representation. The creation and support of Black newspapers became important goals, just as Black antislavery thinking began to diverge seriously from the Garrisonian approach, with its emphasis on moral suasion rather than voting and political activism. By the mid-1840s there was serious discussion of the need for a Black national print organ. At the 1847 National Convention in Troy, New York, “The Report of the Committee on a National Press” suggested:

Let there be, then, in these United States, a Printing Press, a copious supply of type, a full and complete establishment, wholly controled by colored men; let the thinking writing-man, the compositors, the pressmen, the printers’ help, all, all be men of color;-then let there come from said establishment a weekly periodical and a quarterly periodical, edited as well as printed by colored men; let this establishment be so well endowed as to be beyond the chances of temporary patronage; and then there will be a fixed fact, a rallying point, towards which the strong and the weak amongst us would look with confidence and hope …

The printing committee foresaw the financial difficulties of sustaining a newspaper such as this, which, they predicted, would require 2,000 regular subscribers. As an alternative, the committee recommended designating an existing paper to play the envisioned role. One year later, at the Colored National Convention of 1848 in Cleveland, Frederick Douglass’s recently established North Star was identified as serving the function of a national Black newspaper.

Between 1830 and the end of the nineteenth century, scores of proceedings were printed in newspapers and as pamphlets, and even as handbills around the country. The strategy worked to publicize the meetings as they were happening, but made it difficult for historians to get a full sense of the published minutes as a body of texts. The print record of the movement was characterized by dispersal. Some sets of proceedings made their way into the collections of historical societies, archives, and libraries. The lack of centralized records reflected the absence of an anchoring, permanent central organization. (The national organization that had been envisioned by Douglass in 1853 never came into being.) Rather, the absence of central records was a result of separate, though often related, decisions to call national, state, or regional conventions in response to events as they unfolded. A researcher working during the pre-digital era had to cover a lot of territory to consult all the minutes that were extant, and even the most intrepid researcher would have been unable to locate many. This situation prevented a comprehensive assessment of the movement by historians. This is the gap that the Colored Conventions Project seeks to fill.

Twentieth-Century Developments

Several volumes of collected minutes appeared during the second half of the last century. In 1969, Howard Holman Bell’s Minutes of the Proceedings of the National Negro Conventions brought together proceedings from the twelve national conventions that took place between 1831 and 1864. For some reason, Bell does not indicate the archival sources of his facsimiles, with one exception, thus leaving readers in the dark as to where he had located the facsimiles that constituted the book.

He gives a fuller accounting in his doctoral dissertation, A Survey of The Negro Conventions Movement (1953), published as a book in 1969. Like so many other scholars doing research on African Americans during the 1940s and 1950s, Bell acknowledges the contributions of influential Howard University librarian Dorothy Porter Wesley to his project. He names Howard as one of the repositories with the best collections of pamphlets, along with Yale.

Bell notes that the pamphlet reports are official accounts of the conventions, but that in some instances they lack pertinent information or become clear “only when supplemented by newspaper reports” (iii). However, he affirms the importance of printed minutes as sources of information. Minutes provide lists of attendees as well as committee rosters. They lay out plans that were outlined at the meetings and speeches attendees made for or against these plans. Even in the absence of other information, these details are invaluable to researchers and students of the movement. Often the minutes are the only source of information regarding the identities of those involved in the movement, as well as the principle strategies and debates. Bell’s observation about the suppression of certain details in the published minutes might be illuminated by an observation made by Spires, who explains that conventions sometimes refrained from providing full details of heated debates, for example, lest there be accusations of disunity in the ranks.

In the introduction to one of their two volumes of proceedings from state conventions (1840-1865), Philip S. Foner and George E. Walker lament Bell’s failure to indicate the sources of the minutes he republished. Foner’s and Walker’s volumes were published in 1979 and 1980 (the two scholars co-authored both volumes). They assemble transcriptions of 45 conventions from fifteen states. In 1986, the two also edited the first of a projected three-volume collection of proceedings of national and state conventions that took place between 1865 and 1900. Fortunately, all three volumes indicate the newspaper or other source of each set of proceedings. These details have been vital to the Colored Conventions Project, which has drawn from these sources, and gone on to offer a much larger number of minutes, which can be searched using keywords.

While the volumes produced by Bell and by Foner and Walker were valuable tools for scholars of African American history during the decades after their appearance, they are now out of print and hard to find. Also, even these capacious resources omit many sets of proceedings, particularly from the state conventions. The Colored Conventions Project drew on the published collections for the first scans that made their way onto coloredconventions.org. Since then, the site has added scores of conventions from archival or online sources. Many had been rarely cited, and some had never been cited at all. New sets of proceedings are being discovered and added continually by the faculty director of the program, as well as by the graduate students, undergraduates, and librarians who make up the project team. And there are more discoveries all the time. At the recent Colored Conventions Symposium in Delaware, scholars pointed us toward groups of proceedings from Texas conventions. We are in the processing of obtaining images of those documents in order to make them available. These minutes should allow researchers to get a sense of the distinctive features and concerns of the Texas conventions movement.

Reflecting on “Hybrid” Texts

Project co-coordinator Jim Casey and other scholars often point to the hybrid nature of the convention proceedings. As seen above, the conversation created by this archive includes preliminary announcements, minutes in newspaper or pamphlet form, and post-facto commentaries in the form of letters or newspaper articles. In some cases they also include resolutions and petitions such as the one that delegates from the 1840 New York State Convention sent to the legislature to protest the exclusion of Black men from the voting process. Bell’s remarks about the importance of the minutes as historical documents show that juxtaposing these linked, heterogeneous sources is necessary to historical reflection on the topic. Not only is the Colored Conventions Project disseminating the constellation of documents that come out of individual conventions, the project is also allowing researchers to read all the available minutes together, or to search across them for names or themes. This tool has the potential to revolutionize understanding of the conventions movement. Reactions from our 2015 symposium suggest that scholars strongly agree. One attendee proclaimed on social media that his research agenda was changing before his eyes.

The Next Phase

In her introduction to the online exhibit documenting the printing of convention proceedings, curator and CCP co-coordinator Sarah Patterson points out that a full publishing history of the Colored Conventions movement remains to be written. By assembling the largest collection of minutes in the world and making them searchable in new ways, the Colored Conventions Project is already contributing to the writing of that history.

Further Reading:

The Colored Conventions Project Website has an extensive bibliography of sources relating to the Colored Conventions movement and nineteenth-century African American political advocacy. Derrick R. Spires’s “Imagining a State of Fellow Citizens: Early African American Politics of Publicity in Black State Conventions,” from the book Early African American Print Culture, was particularly helpful for the writing of this article.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Curtis Small is a special collections librarian at the University of Delaware. Most recently he has been assisting the Colored Conventions Project with obtaining permissions and with tracking down and acquiring new sets of proceedings. Working with the project has inspired his interest in the print history of the Colored Conventions movement and in African American print history more generally.