The Colored Conventions Project and the Changing Same

Beginning in 1830 and continuing for decades after the Civil War, Black communities sent thousands of delegates to multi-day state and national colored conventions. There, representatives considered resolutions to advance educational and labor rights, voting and jury representation and the role of the Black press. They debated the utility of jobs in the service sector, the power of owning one’s own land and businesses, and how to best support the self-emancipated, the still enslaved and the newly freed. They gathered and disseminated data about Black occupations, property and institutional affiliations. Earnestly, and often angrily, they questioned whether or not this country would—or could—ever deliver on its democratic rhetoric when it came to a people its national founders and founding documents disparaged and degraded. What options could advocacy and emigration offer, they deliberated over and again, if that answer were no.

Unlike any other nineteenth-century effort for racial justice, colored conventions speak to the ongoing issues Black people face as disenfranchised denizens of the United States and as global, diasporic, citizens of the world. The abolitionist movement, and in the U.S., the Underground Railroad, are the lenses through which scholars and the public almost habitually view nineteenth-century movements to advance Black freedom. Often viewed as symbols of interracial cooperation led by courageous whites and a select group of individual Black abolitionists, both abolition and the UGR formally end with slavery’s official demise, literally closing the doors of the institutions and print organs that supported their work as the Civil War waned and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were passed. Public narratives often repeat these tropes of white bravery and leadership and of interracial cooperation. The Black agency and the intra-group cooperation, complexity and heterogeneity that the colored conventions display across region, status, denomination, decades and interests, rarely take center stage.

The Colored Conventions movement shares the chronological genesis of the antebellum movement against Southern slavery. But though it begins in 1830 at Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel AME Church, it swells rather than stops in 1865. Indeed, in the churches and halls in which they met, attendees fleshed out issues that reached well beyond the thematic and temporal boundaries of slavery; they insisted on their claim to dignity and to full human and citizenship rights. They demanded that their children be free not only to survive the violence meted out by the state and its recognized citizens—but also to thrive and prosper. Far from being centuries removed from the pressing concerns of today’s Black organizers, parents, community leaders, and laborers, the scenes and scenarios discussed at these conventions speak directly to the value of Black lives and to the continuously necessary assertion that they do, in fact, matter, then as now.

When delegates to the 1865 “State Convention of the Colored People of South Carolina” met on Charleston’s Calhoun Street, they gathered “for the purpose of deliberating upon the plans best calculated to advance the interests of our people [and] to devise means for our mutual protection.” Convening in the heart of the Confederacy less than a year after its fall, among their first orders of business was a motion to appoint “doorkeepers” and a Sergeant of Arms. This six-day meeting was held in Zion Church, which stood “nearly opposite” to what was slated to become—that very month—Mother Emanuel AME Church’s first new building since it was forced underground after the famous revolt planned by one of its founders, Denmark Vesey. “Resolved,” they declared, “that we will insist upon the establishment of good schools for our children throughout the state.” In their “resolve,” they echoed and anticipated the issues that resonate in that state, indeed that still resound quite deeply, as we mourn the death of the Emanuel 9 and reflect on the ongoing fight for educational, legal, bodily and representational justice in South Carolina—and well beyond it—in 2015.

The Beginning of the Colored Conventions Project: Turning a Class Assignment into a Leading Digital Humanities Project

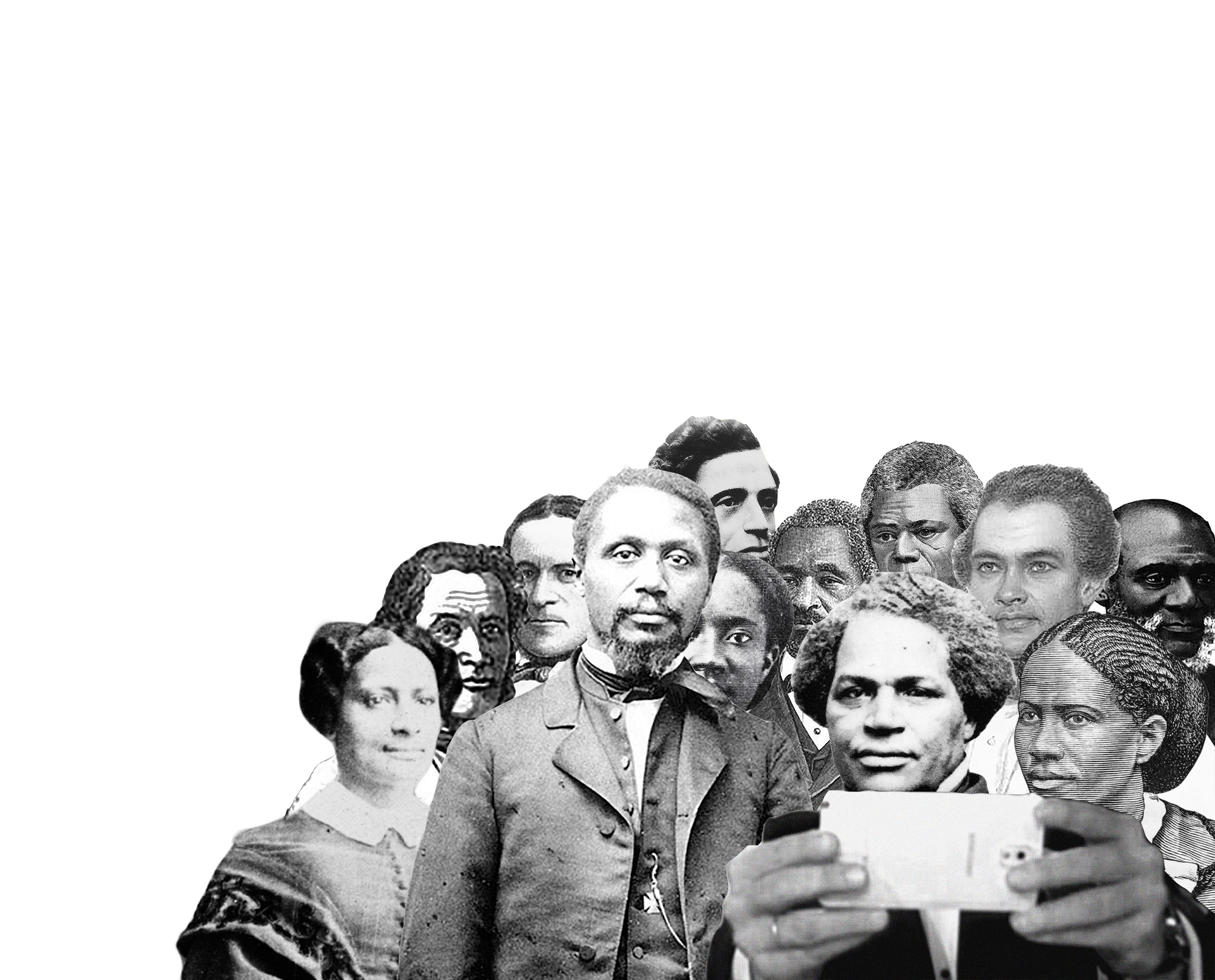

The Colored Conventions Project (CCP) started in a graduate class in 2012 when I assigned each student a delegate from the 1859 New England Convention and asked each to create a Facebook page, upload pictures and friend other delegates after unearthing, in relatively new databases, newspaper coverage, publications and images most of us had never seen (fig. 1).

As J. Sella Martin, George Allen, Jermain Loguen, William Wells Brown, and George Downing made their twenty-first-century appearance on social media, the minutes and delegates who attended that convention came alive: we could examine the frontispieces of their narratives, log their travel and see how their personal and professional circles overlapped. (This was before Facebook abandoned the sophisticated maps and apps that visualized social networks and geographic circuits.) After their seminar presentations, Sarah Patterson and Jim Casey, now CCP’s co-coordinators, asked questions that helped launch the project. Sarah posed, as politely as she could to a new faculty member known for making Black women’s roles in the nineteenth century central to her intellectual enterprise, “why replicate the exclusionary biases embedded in the minutes when we know that the history itself was richer and more complex?” What can we do to push against and resist the gendered limits of the archive—the minutes we were mining—she asked? Jim Casey pointed out that Facebook is a commercial site, not an educational one; as soon as its algorithms discerned that William C. Nell and Amos Beman weren’t consumers, but that their creators were, it would shut down those pages. This was too interesting not to continue, he added; why not shift to a platform not driven by capital production?

The class voted. We moved to Omeka. The semester ended. We continued to meet weekly. Recruited a design professor. Brought in undergraduate researchers. Added graduate students from across disciplines. Registered a domain name. Partnered with librarians. Created research guides. Located more minutes. Crafted a curriculum. Brought in national teaching partners. Continued working on top of our regular loads. Stopped sleeping. Convened a grants committee. Secured funding. Compensated student researchers and graduate leadership well. Facilitated a transcription initiative. Brought on a historic churches and community liaison. Partnered with the AME Church. Created exhibits. Brought on a computer scientist. Launched a major database. Crafted a generous permissions agreement with Gale Cengage. Became the subject of an NPR video.

Soon coloredconventions.org (fig. 2) was the first place to digitally bring together convention records that had appeared beforehand only in rare and out-of-print volumes or in repositories that had never made them available. In the three years since that assignment, almost a thousand students have been exposed to the conventions and engaged in original research writing cultural biographies about the locations in which they met, the songs conveners sang, associated women and the delegates themselves. In spring 2015, we held what we believe is the first symposium that took the convention movement as its focus—(think, if you will, of how many have been held on the Underground Railroad and abolition movements). We are now editing a volume, Colored Conventions in the Nineteenth Century and the Digital Age, that will fully interface with coloredconventions.org. Digital exhibits complementing the essays will be included in this collection, the first to address the movement, are also on the docket. We hope the database the project is launching will likewise support scholarly and independent research for decades to come.

Mapping Connections, Remapping Archives

The conventions themselves highlight the activism and interconnections between known and relatively unknown Black reformers, from the giants of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century to those who carried Black activism into the twentieth century. AME founder Bishop Richard Allen lobbied to have the 1830 inaugural convention held at Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel Church; and Abraham Shadd attended all five of the early conventions. Mid-century icon Henry Highland Garnet at 25 attended his first New York state convention in 1840 and continued to be present at a score of others until just five years before his death in 1882; Frederick Douglass, who made his debut at the famous 1843 national convention, was equally active. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, the last of the AME Church titans known as the “Four Horsemen,” called for a National Colored Convention as late as 1893. Newspapers such as California’s Mirror of the Times sometimes were founded in direct response to convention calls. And editors such as Douglass, Martin Delany and the Colored American’s Rev. Charles Ray were attendees alongside the era’s most prominent businessmen and pastors. Sometimes women appear directly in the minutes, such as the Provincial Freeman’s Mary Ann Shadd Cary, whose presence was debated before her speech at the 1855 Colored National Convention (it was reported in papers some twenty years after her father’s last appearance as a regular delegate). Author and activist Frances E.W. Harper gave the keynote at Delaware’s 1873 State Convention (fig. 3).

Despite this richly networked print and activist history, scholarship often reproduces the tropes that emerge from historiographical choices and archival structures that replicate neo-liberal modes of domination, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History brings home. For example, Rev. Charles Ray’s online biographies stress that he “dedicated most of his life to the abolitionist movement” and highlight the opportunities abolitionists (read: white patrons) opened up for him. This despite his role as an editor of the Colored American, as a prominent pastor, and his more than twenty years living and working beyond slavery’s official demise. Likewise, Douglass’s life often unfolds in relation to white collaborators William Lloyd Garrison, Julia Griffiths, and Ottilie Assing. In biography after biography, article after article, Douglass is embedded in the social relations that reproduce his connections to whites—when he also spent many important hours traveling to, and also in, the Black spaces in which the Colored Conventions movement is grounded. Mifflin and Jonathan Gibbs, brothers who excelled in the roles of newspaper editors, businessmen, reverends—each later became prominent Reconstruction state elected and nationally appointed officials—met or strengthened their relations to Douglass and figures crucial to their lives at conventions. As young men they accompanied Douglass to Rochester, where he became a mentor and patron. With antebellum abolition taking center stage, however, these stories of Black connection and Black sponsorship are relegated to the margins.

Creating a New Archive: Recovering Women’s Roles

Placing colored conventions at the center of historical discussions about African American justice and the nineteenth century raises the danger of women being shunted off to the margins if only in the name of fidelity to extant records—the minutes themselves. But the Colored Conventions Project’s mission, like the symposium it hosted, deliberately highlights women’s roles as we also interrogate the definitions of public and domestic space in relation to social and political networks. Early Black subjects participated in “shadow politics” in “the mimicry of formal political activity in black-controlled institutions,” as Richard Newman defines it. To modify the description, they participated in a “parallel politics,” that is, in a political practice actualized in the face of exclusion, derision, and violence at worst, and ambivalent and uneven access at best. The antebellum convention movement readied thousands upon thousands of convention delegates, and those to whom reports were read or disseminated, to actualize the post-War promise of democracy. Likewise, Black women were adept practitioners of a politics of influence outside of formal coordinates of power and inclusion, as Elsa Barkley Brown has made clear. It’s useful to broaden the spatial contexts of convention goers from the halls and organizations from which they were sent and in which they met to also include the question: “Where did they stay and what did they eat?” as Psyche Williams-Forson did in her Colored Conventions Symposium paper. This angle of vision inserts (hundreds of) women and children back into the political equation, recognizing the overlapping, augmented, and accreted spheres of activity and intellectual labor that happened in domestic spaces Williams-Forson redefines as “political meeting places before, during, and after the convention day” (fig. 4).

Tracing Roots, Forging Legacies and Today’s Changing Same

Though the genesis of this project, like the inauguration of the Colored Conventions movement itself, is clear, it doesn’t end as much as it streams into rich tributaries that flow from it. In the nineteenth century, the National Association of Colored Women, the Niagara movement, and the NAACP all can trace roots from the rich precedent (and in some moments, concurrent work) of the Colored Conventions. Later convention/association activists such as Frances E.W. Harper and Rosetta Douglass Sprague emerged from families that were active, or who were active themselves, in earlier conventions. W. E. B. DuBois, a founder of the Niagara movement and the NAACP, was a grandchild of Othello Burghardt, who was a delegate from Great Barrington, Mass., to the 1847 national convention. As the Colored Conventions Project seeks to identify as well as make public and searchable more (and particularly later) conventions, we also grapple with larger questions about convention contours and contexts which inform whether or not the decades of meetings have a defined “ending,” what sorts of the many (Black education, Black Republican, Black labor) conventions “count” for the purposes of this project, and whether or not they constitute a movement. What is clear is that the Colored Conventions Project is committed to making available the decades of Black organizing involved in this effort because this activism directly speaks to issues that occupy today’s movements, today’s concerns, today’s changing same. I wrote this during the weeks that mark the murder and day-after-day burials of the Emanuel 9.

Why embark on this digital project as Black people again must ask whether or not—in our everyday lives—the masses can be included in the broader body politic at this late date, while evidence mounts that the answer is still “no” (fig. 5).

This project is dedicated to recovering the history of the Colored Conventions movement and its participants as they advanced Black-visioned, Black-executed efforts that demanded that Black lives and Black equality and Black dignity matter. What we continue to learn from these minutes, from this movement, speaks across time and place, speaks to today’s violence and the need for perpetual mourning and movement-building in ways that make them relevant and resonant despite their obscurity, indeed despite their all but erasure as a major force in contemporary history and historiography. We #SayTheirNames as a commitment not just to healing but also to recovery that includes historical and activist redress.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

P. Gabrielle Foreman, faculty director of the Colored Conventions Project, is Ned B. Allen Professor of English and professor of history and Black studies at the University of Delaware. She is finishing a book called The Art of DisMemory: Historicizing Slavery in Poetry, Performance and Material Culture. She will also co-edit the collection Colored Conventions in the Nineteenth Century and the Digital Age.