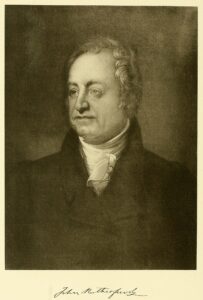

There, in 1771, Temple used the threat of publishing his letters on the Stamp Act to blackmail Thomas Whately (who had taken the followers of the late Prime Minister George Grenville over to Lord North), into creating the post of inspector-general of customs for England for him. Temple enjoyed this sinecure until 1773, when the Massachusetts House of Representatives published sixteen private letters between Thomas Whately (who had died in 1772) and Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver. The letters were political dynamite. The Massachusetts legislature petitioned the king to dismiss Hutchinson and Oliver. In England, Thomas Whately’s banker brother, William, suggested that Temple might have taken the letters from his late brother’s files. Temple took umbrage at this and challenged the banker to a duel. It was bloody and inconclusive. To head off another duel—and to protect his real source—Benjamin Franklin published an admission that he had been the one to purloin the letters. The result was that both Franklin and Temple lost their government jobs, and Parliament was in a vindictive mood when news arrived of the Boston Tea Party.

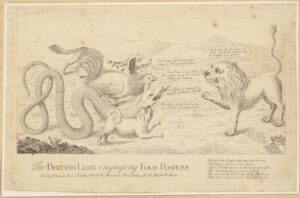

During the War for American Independence, John Temple went back and forth between England and America, trusted by neither side. He landed a post on the Carlisle Commission, created to end the war by granting America all its demands except independence. The commission failed, and Temple was notably dilatory in his duties to it. Lord North’s government decided that Temple had not earned a promised baronetcy. And in America, John Hancock, a bitter political rival of Temple’s father-in-law, James Bowdoin, got Temple placed under a heavy bond to behave properly. The debate over Temple’s status filled the Boston newspapers for nearly two years.

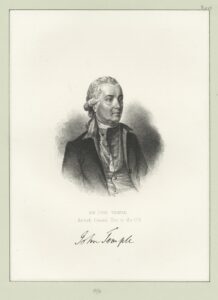

Realizing he had no political future in America, Temple took his family back to London. The British government was in no hurry to establish diplomatic relations with its erstwhile colonies, but merchants on both sides of the Atlantic were anxious to get trade moving again, which required the services of a consul general. Temple lobbied hard for the job and once again used his family connections (Prime Minister William Pitt was also related by marriage). He was greatly assisted by the fact that the man the government really wanted, Phineas Bond, was under sentence of death for treason in Pennsylvania, and the Confederation Congress was highly unlikely to accept him. The government likely saw Temple’s main value as a stalking horse. (If so, it worked: Bond was quietly accredited as the second British consul general in 1786, and he soon took over many of Temple’s responsibilities.) Congress accepted Temple as the first British diplomatic representative to the United States in December 1785. He styled himself “His Majesty’s Principal Servant” in the United States, and when shortly he succeeded to the Temple family baronetcy, his self-importance knew even fewer bounds. Thus John Temple was acting completely in character when he sought the indictment of Senator Rutherfurd.

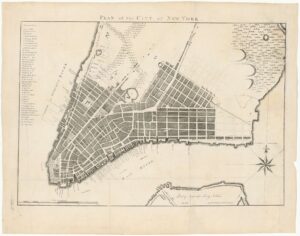

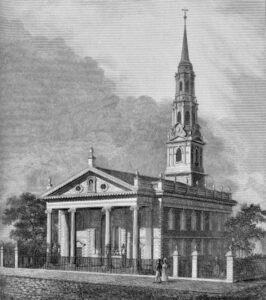

John Adams rather liked Temple (a sentiment Temple did not reciprocate) and was hopeful but wary about Temple’s appointment as the king’s representative. Adams feared that Temple would forget his primary responsibility to the king and try to be an American at the same time, causing conflict between the two nations. In this Adams was as prescient as he has proved to be in most things. In the perennial dispute between England and America over impressment of seamen, Temple took the American side. Lord Grenville ran out of patience in 1798 and ordered Temple back to England, undoubtedly to dismiss him. Before Grenville’s letter arrived, however, on November 17, 1798, John Temple died of an aneurysm. He is buried in the churchyard of St. Paul’s Chapel in lower Manhattan, the church where George Washington had been inaugurated as the first president of the United States.