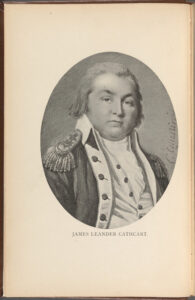

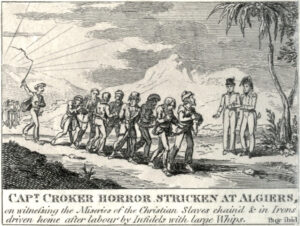

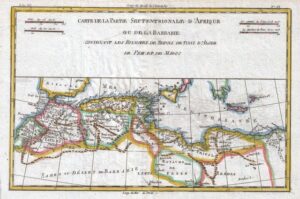

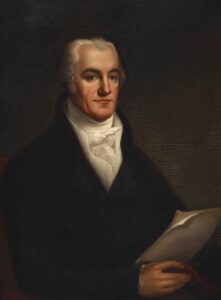

Cathcart’s abilities to understand and manipulate people, his capabilities with words, and his belief in the power of words are all clear in his experiences in Algiers in the late eighteenth century. And those same beliefs and capabilities influenced the creation of The Captives: Eleven Years a Prisoner in Algiers and of the hero at its center. Though Cathcart’s contemporaries dismissed him as, at best, a mediocre diplomat, the use of words in his personal narrative suggests a political understanding we still see today—if I write or speak something, it just might make it “real.”

Note on Sources:

Cathcart’s narrative was brought into print by his daughter, J. B. Newkirk, in 1899, and is available in online archives. It is also available through reprint services; the reprint referenced here is the unedited 2017 printing by Andesite Press. Some of Cathcart’s letters and original journal were also consulted, by way of the Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, vol. 64 (April-October 1954), pages 303-436, and additional letters were accessed through Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers (1939-1944).

This essay was informed by the theoretical work related to the concept of “performative utterance” of J. L. Austin, How to Do Things With Words (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962); Mary Louise Pratt, Toward a Speech Act Theory (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1977); and Jay Fliegelman, Declaring Independence: Jefferson, Natural Language, and the Culture of Performance (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993). It was also informed by the reading of sea narratives in Hester Blum, The View from the Masthead: Maritime Imagination and Antebellum American Sea Narratives (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). And finally this essay built upon several scholars’ treatments of the historical Cathcart: Lawrence A. Peskin, Captives and Countrymen: Barbary Slavery and the American Public, 1785-1816 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009); Robert J. Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World, 1776-1815 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995); Richard B. Parker, Uncle Sam in Barbary: A Diplomatic History (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004); and Martha Elena Rojas, “‘Insults Unpunished’: Barbary Captives, American Slaves, and the Negotiation of Liberty,” Early American Studies 1 (Fall 2003): 159-86.

This article originally appeared in August, 2022.

Julie R. Voss is Professor of English and coordinator of the English and American Studies Programs at Lenoir-Rhyne University in Hickory, North Carolina. She holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Kentucky, where she first encountered Barbary captives while researching her dissertation on Islam in early national American texts. In addition to this topic, she writes and speaks on women writers and on pedagogy.