The Heart of Audubon

“Please take my good friend to my

Father’s old plantation of Mill Grove,

and show him where first American Ornithology

grew in the heart of Audubon!”

(Letter IV, 1827)

Few figures in American history have weathered as intense a scrutiny of their written work as the celebrated ornithologist and artist John James Audubon (1785–1851). Nearly every scrap of his writing has been transcribed and debated in numerous biographies and articles spanning more than a century, each revisiting the same primary sources in search of a new angle. The first half of his life is generally obscure because his journals and letters have been lost or destroyed, or because there were few to begin with. This is especially true prior to 1826, when Audubon, after ironically failing to find an engraver or publisher for The Birds of America in the United States, crossed the Atlantic to pursue the same goal.

Known primary sources from 1824–25 provide almost no information about his artistic vision for the book. This is especially unfortunate because the genesis of The Birds of America can be traced to this period. Audubon later confessed that he had not thought seriously about publishing until he met Charles Lucien Bonaparte (1803–1857), the French ornithologist, in Philadelphia on April 10, 1824. Four days later, Audubon’s paintings were examined by Philadelphia’s foremost engraver, Alexander Lawson (1773–1846), who was unimpressed and refused to engrave them. A second engraver, Mr. Fairman, felt that Audubon’s artwork was beyond his ability to engrave, and suggested that the ornithologist find someone with superior skill in Europe. (This may also have been the unexpressed reason that the proud Lawson rebuffed Audubon.) On April 15, Audubon wrote in his journal, “I had now determined to go to Europe with my ‘treasures,’ since I was assured nothing so fine in the way of ornithological representations existed.”

Audubon’s journal from this period was deliberately destroyed by his granddaughter Maria in 1895. She later admitted to biographer Stanley Arthur that she had “copied from it all [she] ever meant to give to the public.” The destruction of the journal made it impossible to verify the scattered excerpts that she published two years later in Audubon and His Journals (1897). Indeed, she refused to transcribe most of the journal, feeling that “the mental suffering of which it [told] so constantly . . . the very heart of the man,” should be shielded from public scrutiny. Journal excerpts that appeared three decades earlier in The Life and Adventures of John James Audubon, the Naturalist (1868), and The Life of John James Audubon (1869), also became impossible to verify when the original journal was destroyed. These works had been produced from the same manuscript, prepared by Audubon’s widow, Lucy, and did not differ with respect to the 1824 excerpts.

Five unpublished Audubon letters, unknown to most scholars until now, are reproduced and annotated below. Passed down for nearly two centuries by the descendants of their recipient, the Quaker naturalist Reuben Haines III (1786–1831), the letters fill critical gaps in our understanding of Audubon’s early artistic vision for The Birds of America, and include the only known copy of the original (American) prospectus. Audubon proposed a collaborative and patriotic work that would be a symbol to the world of the strength and agency of the new American Republic. He envisioned a text in which “the idea of each man of judgment and truth being inserted would go toward increasing the imitation of God’s work . . . [Only] then the book would positively contain America and its birds.” But rejection in Philadelphia and New York left him no choice but to abandon that lofty goal for one more practical: to publish on his own without the support of the American scientific community. When The Birds of America was eventually financed and published in Europe, Audubon’s move was perceived by many in America as having been driven by personal gain, and his original (rejected) vision was lost to history. The letters that outlined that vision were held in the Haines family’s private collection, and thus escaped the notice of Alice Ford, whose otherwise comprehensive bibliography in John James Audubon (1964) is still used by modern biographers. I came to know of the letters in 2010, during my tenure as resident caretaker of Wyck, the historic house and garden where Audubon was hosted in July 1824—the home of Reuben Haines.

Reuben Haines was an agricultural scientist, meteorologist, and philanthropist whose role in the early development of American science has been largely forgotten. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society (APS) on October 16, 1813, where he later served as secretary (1814), member of the auditing committee (1814–16), and curator (1819); and to the Academy of Natural Sciences (hereafter, the Academy) on November 16, 1813, where he served as corresponding secretary for 17 years (1814–1831). In that capacity, Haines played a pivotal role in the early success of the Lyceum of Natural History in New York, and kept written correspondence with an extraordinary number of naturalists, including Audubon.

The Return to Mill Grove

Audubon spent his final days in the Philadelphia area at Wyck, the country estate of the Haines family in Germantown. The rural landscape that surrounded Wyck in 1824 has long since been consumed by the expanding city, but the house still stands and now functions as a living museum and urban farm. Haines kept and bred a captive flock of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) at Wyck for over a decade, of which he wrote that the males and females were “so much alike that I could not distinguish them from each other until the breeding season when I could distinguish the males from their motions and voice.” The flock was composed of seven birds by early 1824, but they did not breed as they had in previous years. Haines was concerned and sought the advice of an expert. On July 25, he made the following entry in an unpublished research journal now housed at the APS Library:

John J. Audubon of Louisiana visited me at Germantown. He states he has reared many wild geese, wood ducks, &. &. and has no doubt that my confining them all together prevented their breeding. Had I put one pair alone in the pen he has no doubt they would have bred as usual. He evinced great knowledge of these birds, picked out almost instantly all the males from the females and old pair from the others, and the 1 year from 2 year old.

The next day, Haines took Audubon on a carriage ride to his old home at Mill Grove plantation, where the ornithologist had lived from 1803-05. A note in the margin of Haines’s financial ledger, also housed at the APS Library, reads, “[July 1824] 25. With J. J. Audubon Naturalist . . . to Mill Grove (at the junction of the Schuylkill & Perkiomen). Dined at Wetherills with Isaiah Lukens . . .” Mill Grove and nearby Bakewell Plantation were dear to Audubon, for it was there that he met and wooed his future wife, Lucy Bakewell, and where his ornithological talent and artistry first began to flower. Audubon wrote in his journal of the nostalgic experience:

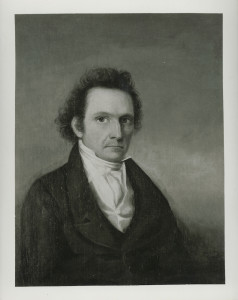

July 26. Reuben Haines, a generous friend, invited me to visit Mill Grove in his carriage, and I was impatient until the day came. His wife [Jane], a beautiful woman, and her daughter [Sarah], accompanied us. On the way my heart swelled with many thoughts of what my life had been there, of the scenes I had passed through since, and of my condition now. As we entered the avenue leading to Mill Grove, every step brought to my mind the memory of past years, and I was bewildered by the recollections until we reached the door of the house, which had once been the residence of my father as well as myself. The cordial welcome of Mr. Watherell [sic], the owner, was extremely agreeable. After resting a few moments, I abruptly took my hat and ran wildly towards the woods, to the grotto where I first heard from my wife the acknowledgment that I was not indifferent to her. It had been torn down, and some stones carted away; but raising my eyes towards heaven, I repeated the promise we had mutually made. We dined at Mill Grove, and as I entered the parlour I stood motionless for a moment on the spot where my wife and myself were for ever joined. Everybody was kind to me, and invited me to come to the Grove whenever I visited Pennsylvania, and I returned full of delight. Gave Mr. Haines my portrait, drawn by myself, on condition that he should have it copied in case of my death before making another, and send it to my wife.

There seems to have been some genuine affection between Audubon and Haines, but there was also a conflict of interest. Audubon had been ill-received by Haines’s Academy colleagues, especially ornithologist George Ord (1781–1866), sitting vice president of the Academy and secretary of the APS, who was financially invested in publishing a second (updated) edition of American Ornithology, the foundational work of his late friend and mentor, Alexander Wilson (1766–1813). Ord was hostile to Audubon from the outset, and his enmity increased dramatically after Audubon accused Wilson (posthumously) of academic fraud in 1831. One year after his trip to Philadelphia, Audubon made a personal appeal to Haines, trying in vain to garner formal support from the Academy despite Ord’s disapproval. Haines’s role as intermediary (or rather, Audubon’s wish for him to be) was foreshadowed in the final paragraph of a letter to Thomas Sully on August 14, 1824, in which Audubon wrote: “Should you see honest Quaker Haines, beg him to believe me his friend; should you see Mr. Ord, tell him I never was his enemy.”

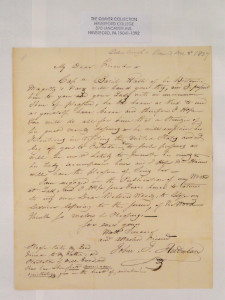

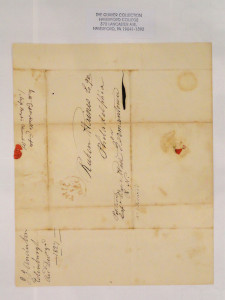

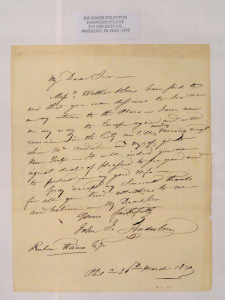

In 1825, Audubon penned three letters to Haines, in which his tone progressed from hopeful (Letter I), to discouraged (Letter II), to near despair (Letter III). Letter II contained an embedded copy of a prospectus for The Birds of America that (Audubon claimed) was sent to the president of the New York Lyceum of Natural History, the botanist John Torrey (1796–1873). To my knowledge, this is the only known prospectus that predates Audubon’s departure for Europe in 1826. Haines did not respond to Letter III. Audubon wrote to Haines again two years later (1827), apparently unsolicited, to inform him that he was “engaged in publication of [his] work at last,” but this letter also received no reply, or Haines neglected to make a note of it on the opposite letter face, as he was in the habit of doing. Letter V was a brief response to an invitation, written during the Audubons’ visit to Philadelphia in 1830. Letters I and V have never appeared in print. Bowdlerized excerpts of Letters II–IV appeared in the late W. Edmund Claussen’s Wyck: The Story of an Historic House (1970), an independently published and locally distributed book that is now rare and out of print. A brief excerpt from Letter III appeared in Patricia Stroud’s biographies Thomas Say: New World Naturalist (1992) and The Emperor of Nature (2000). The following is the first complete, annotated transcript of the letter series.

Mary Troth Haines (1893–1983), the ultimate proprietor of Wyck, transferred the deed for the house and its collections to the Wyck Charitable Trust in 1973. Most of the Wyck documents were deposited at the APS Library in Philadelphia in 1987, but the Audubon letters had been separated from that collection and passed down through the family of Reuben’s great-grand nephew, Robert B. Haines III. Today they are found in a collection bearing Robert’s name in the Quaker and Special Collections of the Haverford College Library, which may explain why these letters have not been previously exposed by Audubon biographers. With a stationary stand, I took perpendicular digital photographs of the original documents, and then, referring to the digital images, carefully transcribed the complete text of each letter. I deciphered confusing words by comparing their letter shapes to those of known words, and retained whenever possible Audubon’s orthographic conventions including (often inconsistent) spelling and punctuation, underlining, and breviographs. Illegible words were denoted with an ellipsis in brackets, and any words for which my transcription was uncertain were enclosed in brackets. Contractions formed with superscript characters were retained, but punctuation marks that appeared below the superscript were omitted. Digital scans and hard copies of this manuscript have been deposited with the Wyck Association for use by future researchers.

The Wyck Audubon Letters

LETTER I