The Hungry Eye, Episode 4

Author’s Note:

As I hope will become readily apparent, The Hungry Eye is a work of historical fiction. Some of its characters and incidents are pulled from the historical record–most particularly, the dueling “special artists” Peleg Padlin and Little Waddley. Their misadventures while touring New York’s netherworld originally appeared in an 1857-58 series of articles in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper written by New York Tribune reporter Mortimer Neal Thompson. That the pseudonymous pictorial reporters stood in for Leslie’s staff artists Sol Eytinge Jr. and a very young Thomas Nast should not be of concern to the present-day reader. Moreover, the mystery at the heart of The Hungry Eye, which entangles these and other characters and the constellation of their relationships, is my own invention. Much of what transpires here (and in the ensuing installments, which will appear in Common-place monthly between January and April) is utterly fantastic–and yet it also, I believe, remains true to the history of a specific time and place.

While I originally conceived of The Hungry Eye as a conventional novel (at least in the sense that it would end up as a tactile book printed on paper with a spine available for cracking) the chance to emulate the once ubiquitous format of serialization was hard to pass up. And wedding an older episodic approach to the still inchoate medium of the World Wide Web offered an intriguing narrative challenge. Aside from requiring some reconfiguring of the story’s structure to accommodate the start-and-stop pacing of extended and intermittent reading, I’ve tried to work with the Web to intermingle the visualization of the past–which plays a prominent role in the plot–with the telling of the story. That said, you won’t come across any state of the art programming here: what I’ve tried to do is enhance the reading experience on the Web, not replace it.

All original artwork © 2001 Joshua Brown.

Episodes 1 – 3 of The Hungry Eye first appeared in Vol. 2 No. 2.

Kit Burns (known to his long-dead mother and father, his as-good-as-dead wife, and the Fourth Precinct’s deadly Captain Thorne as Christopher Kilbourn) cherished constancy. Born in the windowless back of two rooms on South Street, his travels over thirty-six years had taken him no further north than Jones Wood and no further west than Hoboken. Instead of regret, Kit considered his circumscribed mobility as a noteworthy achievement: acquaintances, friends, and relatives came and went in peripatetic panic, leaving the city in search of the main chance only to return months, years later, sometimes shamefaced, sometimes pugnacious, always penurious. In contrast, Kit had hunkered down on the waterfront. And there he had prospered. Not that Kit’s static success set an example for his fellow citizens. Absence, it seemed, generated the adulation of the docks. Those who left and didn’t return, most particularly the lot of Kit’s peers who’d been drawn west by gold fever in ’48, fed the fantasies of those who remained. Sailors were always reappearing, randy and ready to lose their earnings, so the local optimists had turned to speculating about the likes of O’Leary, Hennessey, and Curtis, the most vocal of the b’hoys who’d preached the road to Californ-eye-ay. When years had passed without the trio’s reappearance, the stories began to circulate. They’d found the mother lode and were now leaders of the raw aristocracy of the West Coast; alternatively, they’d deferred that privilege for a purchased enthronement in some Edenic (when you discounted the malaria) Central American backwater. Whatever the story, it seemed to bear an equal portion of pessimism. At least that was the way Kit saw it. The local fantasists constructed fates for the b’hoys that permitted them, once they were deep in their cups, to wallow in the realization that refugees from the Frog ‘n Toe who gained success easily forgot those they left behind. However, when Kit was deep into his whiskey (the result of considerable effort, since Kit insisted on only imbibing the fare he served in Sportsmen’s Hall and that was well mixed with the waters of the River East), he was sure that O’Leary, Hennessey, and Curtis lay buried somewhere among the forests, plains, deserts, and savages he’d seen in the illustrated newspapers. His estimation of their fates back when they’d habituated the Fourth Ward docks had been low enough. In sum, Kit was a firm believer in planning and stasis, and he felt that he didn’t need public admiration to legitimate his dedication to this little spot in the universe that had served him so well. Kit was proud of his three-story kingdom on Water Street, viewing it as a landmark equal to the likes of John Allen’s dancehall just a few blocks away. On a good night, weren’t both establishments bursting with dockhands, sailors, river pirates, and errant swells? True, the penny press tended to dwell on the Bandbox’s badger baiting (and when the badgers gave out, rat baiting), while John Allen’s emporia came across as higher toned if more salacious, its buxom doxies being the staple of the newspapers’ descriptions. But if Kit’s place was deprived of the flash accorded to Allen’s dive, both men contended for the appellation of the Most Wicked Man in New York, a mark of notoriety among a select group of the city’s residents that made Kit’s barrel chest swell with pride. Nevertheless, Kit’s prosperity was burdened with the freight of vigilance. Having leased Sportsmen’s Hall a decade earlier, he maintained his position as a local entrepreneur through the careful marshaling of his resources. Indeed, Kit maintained a clutch of doxies on the second and third floors of his own establishment. The brothel drew a consistent clientele who, aroused by the pit’s blood and bar’s liquor, eagerly climbed into the girls’ open arms and legs, aware that Kit’s whores might not be as well groomed as his curs, but they put up less of a fight. The girls, however, bore a good dose of belligerence (among other things) and they seemed to reserve much of it for Kit, forever grumbling about the scarcity of meat and surfeit of water in their fare. Not to his face, of course: he received these reports from the dutiful Mrs. McMahon (better known as Mayhem), who responded to such criticisms with only a slightly lighter hand than Kit would have wielded. So, relieved from administering discipline, Kit was free to grumble himself, usually from within the formidable embrace of Mrs. Mayhem who reserved her own arms and legs for him in her ornate, if close, chamber on the top floor of the Bandbox. The damned whores, he’d groan into her cleavage, listing the costs of running Sportsmen’s Hall. What did they know about the pain of running the Bandbox? For example, had they any idea of the significant proportion of his earnings Kit was forced to invest in the ward’s constabulary? The cost of preserving his wary truce with Captain Thorne’s Metropolitans was a favorite gripe of Kit’s. It was a gripe, however, reserved for the Mayhem bed; general knowledge of his transactions with the police would only make many extremely untrusting and untrustworthy citizens nervous. The Slaughter House Boys, among other river-pirate gangs, might look unkindly upon news that Kit transferred a steady stream of cash and discrete amounts of information to Captain Thorne in exchange for the courtesy of running the Bandbox without the interference of the occasional raid. But Kit found his arrangement with the Fourth Precinct increasingly burdensome and nerve-racking, complicated as it was by recent reform efforts that had reshaped the police department. Captain Thorne was now answerable to the state, and Kit suspected that the Bandbox could easily become a negotiable item in one of Thorne’s transactions should the Fourth Precinct fall under the scrutiny of the Albany masters of the Metropolitan Police. Kit had other burdens to enumerate. When he wasn’t ensuring that the police were on his side, Kit had to guard his flanks from the covetous nipping and sucking of challengers to his realm. It was fear that he needed to cultivate, a necessary ingredient that had to be constantly attended to, like the feeding and grooming of the beauteous beasts in his kennel. To that end, Kit had surrounded himself with a small but dedicated squad of dock-rats who knew how to bloody a lip or break an arm or, when such measures proved to be inadequate, deposit a corpse in the East River. Among the nastiest of his crew was his very own son-in-law, whose disrespect for Kit’s daughter–the spitting image of her mother in both girth and temper–was outweighed by his peculiar talent with a razor, not to mention the entertainment he furnished the Bandbox clientele. Known locally as Jack the Rat, the boy often served as an opening act for the dogfights. For ten cents, the lad got the crowd’s blood flowing by biting off the head of a mouse. For two bits, he’d accept a mouthful of rat. The thrills and disgust generated by Jack’s act redounded, as it were, to Kit’s credit, contributing to his reputation as a man whom only the foolhardy or addled crossed. Surely, Kit thought as he now returned to the pit, surely the bearded cove who had tried to turn the fight, the one who was now harassing his bruised but victorious champion, surely he knew the terrible retribution he risked. Surely, Kit surmised, his pockets filled with Butts’s winnings, surely the beard had the backing of additional brawn and sinew if he’d come to smash the Bandbox or steal his dog. Always vigilant, Kit had already instructed Jingles and Brooklyn Johnny to take their usual positions in preparation for a muss. Part XII

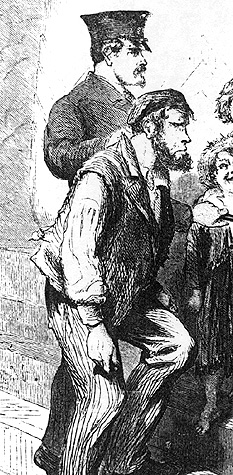

“Now, my boys, what have we here?” Padlin had not noticed Kit Burns’s approach. He seemed to materialize behind the dog, arms characteristically akimbo. Padlin glanced to his left. A rather large and long-armed man stood on the other side of Waddley. One broad and horny hand rested in a less than comradely manner on Waddley’s rigid shoulder. Padlin noticed the nails on the hand were bitten to the quick. The view in the other direction was equally, if differently, uninviting. Another associate of Kit Burns leaned against the pit wall, hands plunged in loose trouser pockets. Slovenly as his dress was, this man was in fact rather delicately made–which was probably why he removed one hand from its pocket to display a closed straight razor. He then took out his other hand so that he could more easily open that implement. A shout–no, a bark–brought Padlin’s attention back to the pit. Moving with admirable dexterity and speed, Burns had strapped a leather muzzle over Jakesy’s mouth. He held its short leash taut, forcing back the dog’s struggling head. Burns patted Jakesy’s jerking side, murmuring, “There, there, my beauty,” but to no avail. He stood up, holding the protesting Jakesy away from him. The dog skittered in a circle, making Burns’s stiffened arm dip and bounce. “What’s your game, mate?” Burns eyed Padlin from under the brim of his fine hat. When Padlin didn’t answer, Waddley cleared his throat: “We are merely Special Artists for Leslie’s Illustrated, sir.” His attempt to rise was intercepted by his captor’s heavy hand. “If you would care to examine my sketches . . . ” “Dry up,” Burns ordered, not bothering to look in Waddley’s direction. “What I care about, see, is some cove trying to dust my champion.” Waddley shook his head despairingly. “We had no intention of disrupting your sport.” Burns jutted his bristled jaw at Padlin. “What does hehave to say about that?” Waddley turned to his mum partner. “Padlin?” his intonation rising fearfully over the one word. Padlin’s repertoire was limited. “Jakesy,” he said. Burns merely squinted quizzically, but the dog suddenly interrupted his agitated dance and lunged toward Padlin. The master of Sportsmen’s Hall lurched forward. He threw out one leg to brace himself, his boot socking the dirt. Cursing, Burns yanked hard on the leash. He looped the lead around one fist and pulled the dog’s muzzled and bloodied snout up toward the rafters. Jakesy’s front paws clawed the air, his back legs prancing in place on the ground. “Johnny!” Burns shouted. Padlin considered how Burns’s anger seemed to coalesce around his wide, flapping mouth, like the limited passion expressed in the snapping jaw of a marionette. Something struck Padlin’s right sleeve. He looked down. The razor was sliding across his jacket arm. The lining winked out in the wake of the slice. The delicate razorman snickered in his ear. And Padlin said, “Mollie Maloney.” This time, Kit Burns visibly startled. His shoulders flinched, his trapdoor jaw gaped. Jakesy, on the other hand, ceased struggling. He sagged from Burns’s hovering fist, twisting slightly. Above the dark leather muzzle, the sky-blue eyes gleamed at Padlin. The reprieve was brief. Burns’s free hand balled into a fist. He stepped forward, dropping his leash-laden arm as he moved. The becalmed dog sank to the ground. Burns advanced to the plank wall, his head tilted back. Padlin watched his puppet mouth, heard “Johnny!” rattle out like a cough. But this time the blade never reached Padlin. Somewhere in its descent, Burns slammed against the planks. His eyes rolling, his hands tearing at the wall, he collapsed. Straddling Burns’s back, Jakesy fell with him and then on top of him. The dog’s paws clawed at Burns’s exposed neck. He pummeled Burns’s head with his muzzled snout. Burns was shouting, trying to turn over, the leash twisting about him like a writhing serpent. Johnny the razorman quit Padlin’s arm and vaulted the wall. The noise rising from Jakesy cut through the curses, a muffled, high-pitched sound that could be nothing else but a scream. It pierced to Padlin’s core and ricocheted up and down his spine. He covered his ears as the deceptively delicate Johnny fell to the pit floor and grappled for Jakesy’s spiraling leash. He barely heard the police whistle. The falsetto wail merged with the dog’s savage cry, only its trill denoting a new presence. A blow against Padlin’s shoulder sent him reeling. He fell between the bleacher seats. His hat struck the wall, driving the brim partly over his eyes. Boots and blue trouser legs trampled about his head, sprinkling the smell of the street’s shit and muck into his nostrils. He heard the familiar hollow thuds of wood against bone and the earthly howls of human pain. He was wrenched upright, shoved, slapped, and punched forward, out of the bleachers, up the aisle. Padlin felt cool, wet air against his cheeks and he caught the rankness of the East River. He managed to wrench one arm free and lifted his hat. A short, mutton-chopped cop grabbed his sleeve and pushed Padlin toward the open doors of a Black Maria. Waddley was already sprawled inside, his pants twisted up, exposing skinny, muscleless calves. Padlin wondered how such sticks could support the heft of Waddley’s torso. “You two,” the cop said, “wait in the wagon.” Padlin tried to twist out of the cop’s grasp. “Find the dog,” he shouted into the florid face. Dwarfed as he was by Padlin, the cop had a murderous grip. “Just get the hell in there!” He kicked out his leg, tripping Padlin who tumbled into the paddy wagon. Padlin pushed himself off the floor, away from Waddley. He leaned his back against the unpainted side of the wagon’s interior. Sensation was rapidly returning to him, an unpleasant trickle that augured a panicky flood. Padlin glanced out the door. Another black wagon was parked a few yards away. Two policemen dragged a man to its doors. One had him by the seat of his pants, the other by his collar. They released their hold and, like a well-trained circus act, the former collar-grabber swung one of the doors into the man’s face and his partner clubbed him into the wagon. “I lost my pad.” Waddley had worked himself up against the opposite side. “I can’t believe it,” he said, shaking his head. He began to straighten out his trousers, emitting little grunts as his stomach bounced against his knees. Padlin could feel the stream of dread growing inside him. “Did you see what happened to the dog?” Waddley looked up. A rueful smile twisted his little mouth. “He speaks! My esteemed colleague, the son of a bitch, speaks!” Before even Padlin, himself, was aware of it, he’d lurched across the wagon, grasped Waddley’s lapels, and thumped him against the wall. “Tell me!” Padlin shouted. “Damn you!” Waddley hollered into Padlin’s beard, his hands around Padlin’s wrists. “Damn you to hell! Leave me be!” Padlin fell back to his side of the wagon. Waddley ran his fingers over his crumpled lapels. “What right do you have to demand anything?” Contorting, he pulled a large plaid cloth from his trouser pocket and wiped his face. Waddley detached his spectacles and began polishing them. “You threatened me with bodily harm this morning. When that attempt failed, you disrupted the dog match to get me hurt. And when that effort failed, you went to the unbelievable extremity of attempting to destroy yourself to destroy me.” Waddley rearranged the wires around his ears and settled his head against the wall. He had regained his composure and his nasty smile. “The irony is that you have me to thank for your rescue. I doubt Quidroon would have called the police to save you.” Outside, in the street, as if cued by Waddley, the fine-boned razorman and his thicker accomplice came into view. His body sagging between two policemen, Johnny’s head lolled forward and the tips of his boots skittered behind. His friend was the greater burden, requiring the rough administration of four officers. He’d lost his derby, but he had a brilliant red stain covering the crown of his head as a replacement. The adjoining black wagon bounced as the two men were thrown inside. Padlin was through with talking. He climbed out of the wagon and watched the police push, pull, and pummel the few other Bandbox patrons who had had the misfortune to linger after the dogfight. Moans and protests emanated from the other Black Maria, momentarily rising with each new deposit, the cops making sure to also apply a few dubs of the club to the already incarcerated clientele.

Padlin slouched against the wagon and conjured his editor’s face in his mind, the expression of surprise and hurt that Quidroon would manufacture if Padlin confronted him, a variation on Waddley’s performance: That’s the thanks I get for rescuing you, Padlin? Yet, as Quidroon feigned distress, his eyes would retain the cold color of triumph, knowing that he had insured his control over the plot of the evening: no matter what Padlin did, it was Quidroon’s story and he had concocted its inevitable conclusion. And what a story it was! The readers of Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper would consume it with decorous glee: blood sport illustrated and avenged: evil and corruption brought to justice: morality preserved. Padlin watched the villain of the piece emerge from the storefront entrance of Sportsmen’s Hall, spread-eagled and struggling, a cop harboring each limb. Once, twice, thrice, the cops swung Kit Burns, a bellowing sack of potatoes, before the entrance of the Black Maria. He disappeared within, his howl trailing behind. Yes, the readers would love the story, duly illustrated by the observant and inventive Little Waddley. The doors of the wagon were slammed shut and the denizens of the Bandbox were carted off. The rattling of the horses’ hooves had diminished when the mutton-chopped cop returned. “Well, that takes care of that,” he said. He contentedly shaved his hands as if he was clearing the grime of crime from his incorruptible person. “We’ll be off now. You’ll inform Mr. Leslie that we performed admirably.” He wasn’t asking a question; he was reiterating the agreed rules of the game. Waddley jumped down and the cop began to walk around to the front of the wagon. Just as he rounded the corner, he turned back and faced Padlin. “You was asking about the dogs before, right?” he said. “You can report that the ones in the Bandbox’s kennel, and a mean bunch they was, are on their way to the pound.” He saluted, as if putting the seal to the bargain, and left. Waddley stood in the center of the street, forlornly looking after the second departing wagon. He scanned the dark fronts of the low buildings. The gaslights were few and far between on Water Street. The shadows of a hundred silent observers filled the windows above them. “I think it would be wise if we departed as well,” he said. Padlin started to walk away. Waddley quickly joined him, his head swiveling at each doorway and alley they passed. They turned off Water Street, moving away from the rough haunts of the seamen and stevedores around Peck’s Slip, toward the lights and traffic of Pearl Street. The prospect ahead seemed to relieve Waddley. He began to whistle. Waddley’s energetic, if off-key, fluting curled around Padlin’s thoughts, which were very much preoccupied with the whereabouts of Jakesy. Padlin knew where the Bandbox’s dogs had been taken, and he knew just as surely that there was no point in his visiting the pound. Among the brawny and battered curs, snapping and mewling as they awaited execution or Burns’s return–their fates teetering on how well he was immersed in the payoffs and favors of Democratic politics–one dog would be missing. Jakesy had escaped. Padlin was sure of it . . . and somehow that realization brought him close enough to the comfort he had been seeking. Jakesy was gone. Padlin embraced that certainty and the vague feeling of release it elicited. Jakesy was gone, taking Mollie Maloney’s unlearnable end and unattainable face with him. Padlin’s exhaustion rushed over him, stemming any further reflection. All he could picture now was the salvation of his unkempt room, littered by the remnants of his unsuccessful efforts of the night before. Tomorrow he would condemn them to the trash. Tonight, though, he would sleep. He was sure of that.

Two toughs were holding up the lamppost on the corner of Pearl and Dover. As Padlin and Waddley approached, they maladroitly detached themselves from their prop and stepped out onto the sidewalk. They were fairly large specimens, dressed for the evening in the beaver hats and red flannel shirts favored by rough sporting men. Their backs were to the gaslight, turning their faces into amorphous masks, featureless in the murk. To Padlin, his mind apparently not yet completely devoid of canine imagery, they suggested Cerebus, the two-headed sentinel of Hades, guarding entrance and egress to the underworld. Waddley bumped up against Padlin, trying to lose himself in the larger man’s shadow. Padlin picked up his pace, not to get by the toughs but to permit them to better spy Waddley’s diminutive aspect. “You,” one of the ruffians shouted, placing himself in Waddley’s path. Waddley hesitated. Padlin brushed by. “You want to fight me, do you?” The tough played with the greasy soaplocks that cascaded from under his hat, corkscrewing the long sideburns. “No,” Waddley said. The wrong answer in an old street ploy. Any answer was the wrong answer. The best response was silence. Walking into Pearl Street, Padlin pictured the bullboy behind him squaring his shoulders, cracking his knuckles in anticipation. “So,” he heard the tough say, “I’m a liar, am I?” Later, Padlin wasn’t sure if he’d actually heard the fist collide with Waddley’s jaw. Part XIII

Kit was a cruel master. His tongue could wag with the most gorgeous phrases–Yes, my beauty–Come to me, my champion–There’s a good boy–but the kind words were belied by sudden, savage blows. Kindness was only delivered after immediate and unequivocal obedience, a kindness limited to lavish meals, slabs of meat, hard and flesh-caked bones. He wasn’t the type to supply a soothing caress, a reticence reinforced by the wounds I applied to his hands and legs when he lowered his guard. After he muzzled me, though, he still kept his distance. The deal probably seemed fair and aboveboard to Master Kit. My pen was vast compared to the birdcages of his other curs; my neck was encased in a leather collar, its inner side padded with cotton, compared to the other curs’ ripping chains; my beatings were short and strategically placed compared to the maulings given the other brutes. On those occasions when Master Kit lost his senses and delivered me a manic onslaught, the stick coming down again and again, the pain reverberating up my spine, down into my testicles, rattling my teeth, on those occasions, invariably, a wave of fear suddenly wafted over his face, a washing of cold sweat that delineated the pits and holes in his face, and my torture suddenly seemed such sweet revenge. I hurt, but Master Kit was tormented, gripped in the terror that he’d done permanent damage to my fighting skills. Cruel masters have been my lot in life, short as that life has been. Before Master Kit, Master Bell exhibited an equally malign character–albeit manifested in a more devious manner. Their contrast, I’m sure, could only be appreciated by a singular creature like myself, one who has experienced the extremities of existence and, thus, knows all too well the spectrum of human cruelties. From nuances of abuse to gross applications of ill will. Master Kit beat me. Master Bell did not. But, whereas Master Kit imprisoned me in a cage and secured my loyalty by leash and muzzle and the occasional lash, Master Bell subjected me to a more terrible fate: he set me free. He set me free to roam the muddy thoroughfares of Gotham. Free to choose my company, free to cavort and consort. Free to achieve the horrible state I find myself in today. I won’t deceive you. I relished the freedom Master Bell permitted me–No. Let me amend that: the freedom Master Bell discarded and which, like any mischievous pup, I eagerly pounced upon. My tasks done, I’d lunge out the door, fleeing his shop. My exit might rouse an oath from his lips, but his rasping remarks were only occasioned by the unseemly tumult of my hasty departure. I couldn’t help but make noise; the anticipation of my nightly reunion with the other pups had mounted over the course of the workday like an irritating itch, blossoming into a maddening rash by evening, and I had to run full tilt like any flea-crazed dog in search of respite. Heedlessly, mindlessly, I swiped past pedestrians, challenging fate as I skittered around horse hooves and wagon wheels. I ran and ran, rapture engulfing me when that blessed street corner came into view. It was merely an angle of sidewalk, bracketed by a streetlamp and the whitewashed window of a policy shop, but it belonged to us. It was headquarters and home, even in the foulest weather, to our mangy squad, all refugees from workshops and stalls. We thought ourselves a remarkable pack. We battled and shoved and challenged each other, testing our mettle night after night against the surrounding traffic. When we weren’t batting one another, we slouched against the hissing streetlight, barking at dandies, howling at damsels, begging for favors from the immigrants and bullyboys emerging from the policy shop. When the numbers were kind, those bettors were an easy touch, throwing us cigar butts and coins along with their usual threats. We only relinquished our spot on special occasions. The clanging bell and clattering approach of the fireladdies sent us into a frenzy and we’d reconnoiter their steam engine as it rounded our corner, its belching smokestack our beacon, leading us to a fantastic conflagration and, if we were lucky, a marvelous battle. Allying ourselves with one company, we’d nip at the opposing fireladdies’ heels, dodging their boots and fists, not to mention brickbats and clubs. And then there were the forays into enemy territory, expeditions to raid another pack’s street corner–or, as often, to defend our own. Oh, those fights were the best, musses that raged for brief moments, a flurry of roaring, yowling, and biting. Victorious or vanquished, almost always dispersed by a cop, we’d return to our haunt, nursing and proudly displaying our rends, bruises, and shallow lacerations. Yes, I relished my freedom and Master Bell said nary a word. Many a morning I appeared in a sorry state, torn and scraped and sore from the previous night’s combat, but all he did was nod in the direction of my breakfast bowl. Only once did he comment and that was early in my wanderings, the one time I whimpered (having loosened a tooth in the evening’s muss). “Fool” is what he said, leaving his wife, my mistress, to crouch down, grasp my nose and extract the worrisome and dying object from my trembling jaw. What did Master Bell care, as long as I observed my duties in the shop, as long as I obediently harkened to his and his jours’ commands, dumbly following the repetitious tasks, as long as I limited my savagery to the after-hours. Only later would I understand the extent of his betrayal and the ignorance to which he had happily consigned me. But the bifurcation of my sunlight and shadow could not be maintained. Let loose and, through my master’s neglect, permitted cultivation, my wildness slowly gained precedence over the rest of my immature being. Slowly, and then with increasing rapidity, the savagery invaded my daylight hours. I barely noticed the change at first. All I knew was that, inexplicably, I’d grow tense, fearful. Soon, I located my unease in the increasing clarity of two of my senses. Smells and sounds would suddenly assault me in the shop, and I’d become confused, my eyesight contradicting the powerful messages entering through my ears and nose. Master Bell gave me an order, nothing unusual, calling me to his side, instructing me to assist him at some task. But his mundane words now sent me into a trembling fit and I stared aghast at his placid, pallid face from which a flood of ire and hate had been disgorged. Somehow, the timbre of his voice, the emphasis of his tongue, had taken on new meaning, and it was as if I looked into his exposed brain, pulsating with wrath, spewing his hatred of me. Smells were even worse. The usual stink of midday sweat coming off the jours cursing at their work became overpowering, rancid with frustration and, at my approach, malevolence. I’d never been popular among the journeymen; I reserved my obedience for my master alone and never displayed the kind of deference the jours felt due them. As far as I was concerned, they were a sorry lot, appearing and departing at a dizzying rate, inevitably dismissed by Master Bell after ruining some piece of work. But, increasingly, the smell of their anger unsettled me, imparting a blunt odor of meanness that enunciated the fate they would’ve given me if they had the chance. It rose off of them and slapped me, a physical blow of a smell, an undiluted odor of murder. I’d freeze before one of them, sure he’d hit me, sure he’d bellowed my doom. But nothing had been done, nothing said. And I took to sniffing, trying to ward off the assaults by catching the first traces of the smells. I’d sit up straight, trying to catch the preceding notes before the awful sounds appeared, my muzzle and ears twitching. It was Mistress Bell who first saw the signs of my increasing savagery. One morning I smelled the suspicion coming off of her and looked up from my bowl to see her standing vigilant beside the stove, her features set in their usual grimace. When she approached to take away my empty bowl, I suddenly felt an urge to nip her, to take advantage of the caution and dread coming off of her dry, cracked hands. Somehow, she must have sensed my purpose for, soon after, I heard her arguing with Master Bell and I was consigned that afternoon to sleep in the shed situated in the dirt yard behind the house. The end came shortly after that incident. I awoke one morning in the shed, startled awake. It was as if all the odors and sounds of the past weeks had coalesced in my head to form a dark warning that urged me, ordered me, to flee. The impulse was overpowering. On all fours, I scurried out of the yard and into the shop. The only way to the street was through the shop’s front entrance, but my escape was blocked by Master Bell, who’d risen early to finish some work for a demanding customer. I tried to control my breathing, to suppress the pants emerging from my throat. My mouth was thick with spittle, unable to contain it so that it speckled upon the wood floor. Master Bell heard me, whipping around from his work. The fear that crossed his face was nothing to the stench. He grabbed a hammer, brandishing it high over his sweating head. I growled. Master Bell yelled. I bared my teeth. He threw the hammer at me. Unthinkingly, I dodged it, the tool bounding off the floor and denting the plaster wall. I leapt for my master. I didn’t hurt him much. He was scrambling up onto the table when I reached him. I got hold of more fabric than flesh, but the taste of the meat of his buttocks was wonderful. My goal, however, was escape, so as quickly as I struck I released him. To the sound of Master Bell’s terrified bleats, I left his workshop forever. The first few weeks I did well enough for myself. The streets of the city being what they are, there was more than enough pickings to keep my hunger in check. All in all, the fare was less fresh but of greater variety than what Mistress Bell had served me in her kitchen. Amidst the garbage lining the curbs and cluttering alleys I found luscious bones, maggoty meat and, when all else failed, rotting vegetables. I quickly mastered the art of intimidation, honing the skills I’d learned in my former street corner pack. A brazen snarl usually did the trick when I found an attractive item already claimed by another cur. Before long I was forced to take more cunning measures; it was easy to fool my challengers–be they dog, pig, or goat–striking suddenly after feigning retreat. The other marauders grew to fear me. If I had wanted to I’m certain that I could’ve gathered my own following of scrawny, scurrying brutes. But the few occasions I permitted some sore-ridden mutt to dog my tracks proved hazardous: invariably, the stupid thing would make a racket, knocking over the barrel I’d led him to, attracting an outraged and armed groceryman. Numbers were a liability in the craft of scavenging. The sounds and smells of the streets augured a universe of opportunities. My senses were sharpened to perfection, directing me to my wants; I need only apply a measure of craft to win, to allow my wits to dissolve in delicious, thoughtless abandonment: the ravening hunger in my belly quenched as I burrowed into a mound of garbage, the pulsing ache in my loins quelled by a moment’s coupling in a vacant field. When the cold weather came, however, my prospects began to deteriorate. My short coat proved inadequate. I came to dread night, lying curled and shivering in doorways, finding meager shelter behind a pile of trash against the freezing wind and rain. As I began to hanker for more substantial fare, rats became my favored meal. Their oily and reeking skins opened to hot, pulsating joy as I broke and swallowed their brittle bones and pulpy organs. Yet, the reward was momentary, incapable of staving off my constant shivering and increasing sleeplessness. I seemed to be slowly shaking off my flesh, my ribs growing more pronounced, my skin tormented alternately by the cold air and the hot ferocity of the burrowing fleas. If I wasn’t scratching, I was gnawing at myself, incessantly pursuing the torturous raging in my filthy, pest-ridden coat. After the first snowfall, my circumstances grew worse. Until then I’d easily dodged and, where I could, menaced the hectoring boys who found sport in running down wizened strays. But that had been when I was in the full flush of my freedom, when I felt my coat was a shining suit of armor, my jaws powerful weapons, my limbs dependable. Now the enemy had an arsenal of ice and snow and a store of energy in direct proportion to my exhaustion. Day after day, hour after hour, tottering on my frostbitten paws, I nervously peered into every alley I passed, checked every stoop, dreading the ambuscades. Finally, one cold afternoon, the sky as gray as the soot-laden mounds of snow blocking the curbs, a squad of boys cornered me. I’d sniffed out a barrel filled with newly discarded refuse, redolent of bones and week-old meat, a delectable, glowing prize perched deep in a blind alley near the docks. How desperate I’d become, how foolish in my pursuit of food. Hesitating at the alley entrance, I raised my nose to the air, cocked my ears, seeking any sign of danger. I thought I caught the tinkle of evil laughter, the conspiratorial snuffling of hunters, the scent of treachery . . . but the cold played tricks on the senses, made the smells and sounds deceptive, near becoming far, far near. The barrel’s sweet stench was stronger than my caution and, impetuously, I darted into the alley. Before I was halfway to the barrel, the shadows of my enemies filled the narrow passageway, blocking any retreat. Screaming and hooting, the boys were upon me. In their ecstatic frenzy, their ice and stones mostly missed their mark. But I had nowhere to go and, as their range shortened, their aim grew truer. A stone knocked the wind out of me, another hit me square on the jaw, sending out a woeful yelp, the kind of sound I’d only heard other curs emit before. I turned, snarling, snapping my teeth, my vision blurred, pain rattling through me. If the girl had not appeared, I’m sure it would’ve been the end of me. In truth, I really don’t know what happened. All I was able to perceive was the sudden swirl of gingham skirts and her high-pitched, rankling voice somehow cowing the hunters, breaking them apart, sending them fleeing. She seemed to know my tormentors, knew their weaknesses and where to strike, not physically but vocally, her slight presence like a hot iron melting away their ice, returning their taunts with threats that forced them back, back, and away. Weak and confused, I cowered from her, snarling pitifully at her approach. Crouching at a safe distance, she met my low growls with fine phrases. She smelled of coal dust and woven rugs, and the gorgeous odor of warm meals came off her hands. Then she stood up, advanced to the barrel, and began to pick out the bits of food that had nearly caused my demise. Cradling the bones and meat in her hands, she built a pile before me and stepped back. She waited there until I relented and crawled over to her offering. In another time I would’ve snubbed her kindness (in another time I would’ve done worse than that), but I was in no condition to disdain her friendship. Once she left the alley I tracked her steps, cautiously following her through the dark, wet streets, halting when she turned to observe my pursuit. She shook her head, but I had learned long ago that appearances meant nothing. The sound of her voice beckoned me. In the following weeks, Mollie Maloney saved me. I insisted on staying in the streets, following her up to but not into the boardinghouse where she lived, going no further than the stoop of the mansion in which she disappeared every morning. Every evening, though, stiff and sighing from her domestic duties, her body thick with the scent of dirt, soap, and food, she graced me with the hearty remains of her employers’ meals. When I wanted it, there was a soft bed of straw in a sheltered corner of the yard behind the boardinghouse. After I allowed her to approach me, she scrubbed me with wet rags, sprinkled my hide with sharp powder, and then set to work with a hard brush. She engulfed me with her caresses, stroking my back until my haunches quivered and my tail ached with its rapturous wagging. And yet, as she stroked me and I gazed up at the flat planes of her broad, freckled face, my eyes inevitably moved to the pulse at the base of her neck. I think now I can say that I felt affection for her . . . an attraction, however, not that different from the impulse I felt when close to the lifeblood of any vulnerable creature. Not unlike what I felt before a kill. It was a confusion I cherished, the tension proclaiming our relationship as unique. Dependent as I might seem in Mollie Maloney’s embrace, I was, in fact, still free. My strength returned, my coat prospered and thickened, my belly no longer mewled. My idyll, such as it was, couldn’t last. I’d learned to avoid the brutal boys, but there were worse predators afoot in the city. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had gained an admirer, an observer who bided his time, lulled me into trust, and then took me as his prisoner. Worse still, my imprisonment would spell the end of the one human who had never betrayed me. At some point during the weeks I was, at least in appearance, Mollie Maloney’s ward, I came to the attention of Master Kit. I first spied him on one of my rat-catching forays on the waterfront. Despite Mollie’s meals, I had not surrendered my taste for rodents and the river’s edge was alive with them. They were particularly succulent along the docks, plump from the raided stores of the ships and warehouses. And easy to catch, their waddling flight no match for my newfound agility. One day I looked up from a catch, my mouth gory with rat remains, and espied a blocky figure on the pier above me. Standing arms akimbo, his legs spread wide against the pestering waterfront wind, he silently observed me. Taking no chances, I ran off, scrambling away from the river and back into the crowded streets. Within days I saw the man again. There was no doubt about it, he was looking for me and, in time, I was fool enough to let him come near. He was patient, an attribute he would relinquish once our association became more intimate. He didn’t try to catch me, always staying a respectful distance, after a while shouting kudos when I performed a particularly noble feat. Of course, Master Kit’s notion of nobility had its peculiar edge and I think it was that strange quality that lured me to him. You see, he seemed most admiring when I displayed my more bestial traits. I think it was on the occasion when I was attacked by one especially stupid boy that I finally came under his influence. Master Kit had shown up as usual, watching me from across a narrow, shadowy street, propped against the bins outside a shabby grocery. I wasn’t doing anything purposeful, I was just sniffing the air for possible diversions when a boy came lurching out of a doorway. He clearly thought he had me as he advanced, making no mystery of his purpose, snorting in anticipation, his upraised arms pressing back his ears, at their apex a large paving stone. I didn’t run; I waited. When he was almost on top of me, reeking with the utter joy of impending murder, I deftly slid between the little lout’s legs. Top-heavy already, my maneuver cracked whatever equilibrium he still maintained. The boy went over backwards, emitting a satisfying screech. Then, unable to deny myself complete triumph, I neatly turned and nipped his collar. I dragged him a few howling feet through the mud before I let him go. As I scampered away, I glanced toward Master Kit. He was laughing with such exuberance that he was bent double. “That’s showing him, Butts,” he shouted when he could control his mirth, “that’s my champion!” “Butts.” I’d heard him use that word before. Its intonation suggested that it could be another name for food, for fondling. Mollie Maloney used the word “Jakesy” in a similar manner. The distinction was arbitrary, at least that’s what I thought then. What was important was that here was a new ally, one who appreciated the subtler arts of my canine existence. Mollie Maloney gave me sustenance and the pleasure of a graceful touch, but I could never show her the gaslight side of my nature. Here was a human, I thought as I sauntered round the corner, who knew my essence and it gave him cheer. The art of Master Kit’s deceit was all in the preparation. Suffice it to say that his patience and distant praise succeeded in casting me in a trance. A few days later, he finally offered me a more material reward and, throwing all caution to the wind, I accepted the dripping slab of meat. I awoke to find myself in a dark stall, my head too heavy to raise from the layer of straw that covered cold, hard-packed dirt. The constriction of the collar around my neck should’ve sent me into a paroxysm of rage and panic, but the pain in my head took precedence. After a while, I worked myself to my feet and wobbled toward the faint smell of the river that wafted through the stall’s open front. It was only after I suddenly gagged, my neck snapped and I flopped back onto the ground that I discovered that the collar around my neck was secured to the far wall by a chain. Collapsed, muddled, miserable, spears of straw stabbing my lolling tongue, my drugged senses eventually discerned the sounds surrounding me in the dark, an uneven song composed of chanting barks and protesting yodels, a captives’ chorus. I was just another dog now, one of many in Master Kit’s basement kennel. In time I learned that, in truth, I was not just one of the mutts Master Kit lured to his prison. He’d marked my craft and agility, he had special plans for his “Butts.” I learned that each dog had his purpose in the Bandbox. The more docile ones, deluded by a regular supply of food and a bed of straw into believing imprisonment was no more than the domestication for which they had always hankered, those gentle and pathetically grateful mutts served as Master Kit’s decoy dogs. They were the only ones who saw daylight unhampered by collar and chain, let out to gather even more gullible strays and errant pets into a pack to be corralled, sacked, and dumped into the kennel. Out of this ever-gushing stream, Master Kit selected worthy candidates for the fighting pit, sending the scrawny and diseased to the pound to meet their deaths (collecting a bounty for each prospective carcass). As for the other dogs, they were divided into two categories, each destined for the amphitheater on the ground floor. The small and fleet ones were dispatched as rat-killers, the laborers of the pit, the clowns in the show. Those of us with brawn were reserved for the service of dog fighting. Of these dogs, the more brutish merely served their time as jours for the few of us who tempered strength with an equal measure of wits. My ears clipped, my hide marked by the slice of teeth and claws, I learned to kill. I learned that what I’d thought were heroic musses, my former street corner battles, were nothing more than a valueless apprenticeship. Once it became clear that any dog I faced in the pit meant me harm–and there was no mistaking that, no subtlety, just a riotous approach and snapping jaws–once it became clear that the kennel and the ring were my home, like it or not, I took to my studies. Master Kit trained me to kill precisely. Placed in the ring, my muzzle removed, I vaulted from his hands like lead shot fired from a musket: that was the sum total of what Master Kit wanted. But I brought something special to the craft, a bravado and daring that amazed Master Kit and made him, in his own way, appreciative. Reducing my talent to its simplest aspect, I brought a sense of time to the pit. It was a skill no one could’ve taught me; it was, I came to believe, my calling, the purpose for which the Almighty had created me as a singular creature. I, and I alone, could parry and thrust, could nibble and bite at the physique and the mind of my opponents, could draw out a fight like a blood-‘n-thunder performance until the surrounding faces were lusting for death. When I finally struck the fatal blow the chamber shook with the crowd’s cry, a rolling thunder of rapture, relief, and repugnance. To use Master Kit’s argot, I gave the crowd its money’s worth. I became the champion of champions, a legend. And now I am nothing. The riverfront is my haunt, at least for the present. I live, caked in the river’s slime, emerging only at night, like the other animals and men who emerge from their holes, from underneath the docks, out of the clay and muck once the sun sets. I can’t catch the rats any more, but it’s not due to any lack of strength. Maybe it’s because I lack the determination . . . because I’ve changed again. For now, I live off of the worst refuse provided by the city. It seems an appropriate reward for one who cannot find a place in the natural order of things. Keenly watching the offal ship moving out of the harbor in the low evening sunlight, the heavy air carries the hysterical flutter of the gulls’ wings and the promise of sustenance. Soon I hear the splash far off in the bay of horses, cows, pigs, and, yes, dogs, the sounds that promise to still the coiling emptiness of my own pit. I force myself to be patient, knowing that the cargo of corpses will return with the tide. My eyes scan the sparkling current of the river, searching for the glint of the bloated rafts in the moonlight, the slithering movement of floating entrails released from bellies burst by the hulls of riverboats. Soon they will drift to the shore. With eager anticipation, I await their arrival.

Go to The Hungry Eye, Episode 3

This article originally appeared in issue 2.3 (April, 2002).