The Lincoln We Hope For

What we all believe about Abraham Lincoln is this:

The extraordinary thing about the life of Abraham Lincoln is how intensely typical it was. The son of a poor farmer, his honesty, diligence, and insatiable appetite for books and homespun witticism ensured he rose quickly from the log cabin of his youth to the relatively polished

It’s not that what we all believe about Lincoln is wrong. But what is actually extraordinary about the life of Abraham Lincoln is how intensely typical it has become. Lincoln has become the personification of the nation’s self-reinvention, its ceaseless quest for moral worth, not because he always already embodied in an angular six-four frame American ideals of diligence, democracy, and self-government, but because we all hoped so badly that he would that we have clothed those ideals in his image. We have taken Lincoln’s virtues and made them America’s. If George Washington is the father of the American civic religion, Lincoln is its savior, whose embodiment of virtues brought to his nation salvation.

This is the Abraham Lincoln of America’s monuments: the man whose rude and crude beginnings have been carefully enshrined, their roughness preserved—as it must be—but also somehow sanitized and sacramentalized, like the fingerbones of Catholic saints, into a vehicle of democratic self-determination. Because Lincoln made himself a president, we can grasp our dreams; because he saved the nation for us, we have that possibility.

The Smithsonian’s exhibit, Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life, stands in a small chamber just off of the National Museum of American History’s most popular exhibit, The American Presidency: A Glorious Burden. That exhibit takes up nearly a dozen overcrowded and brightly lit rooms in the center of the museum’s third floor, joyfully jumbling together Warren Harding’s pale blue silk pajamas with George Washington’s dress uniform, a filmed tribute to movie presidents (Kevin Kline as the cheerful klutz “Dave;” Charlton Heston curling his lip as Andrew Jackson; the paternal gravitas of Jed Bartlet) with recordings of key inaugural addresses (Kennedy, Reagan, Roosevelt; the usual suspects), and a dollhouse belonging to Grover Cleveland’s daughters with the bloody pages of the speech that survived an attempt on Theodore Roosevelt’s life. The walls of The American Presidency are a brisk pale orange, the display cases overstuffed, the lighting bright and cheerful. Children jostle for the chance to stand behind an inaugural podium and visitors fiddle with a computerized display that allows them to vote for their favorite presidents. The tone here is magnificently American: celebratory, confident, a bit playful, and not just a little triumphal. It’s the life which death made possible.

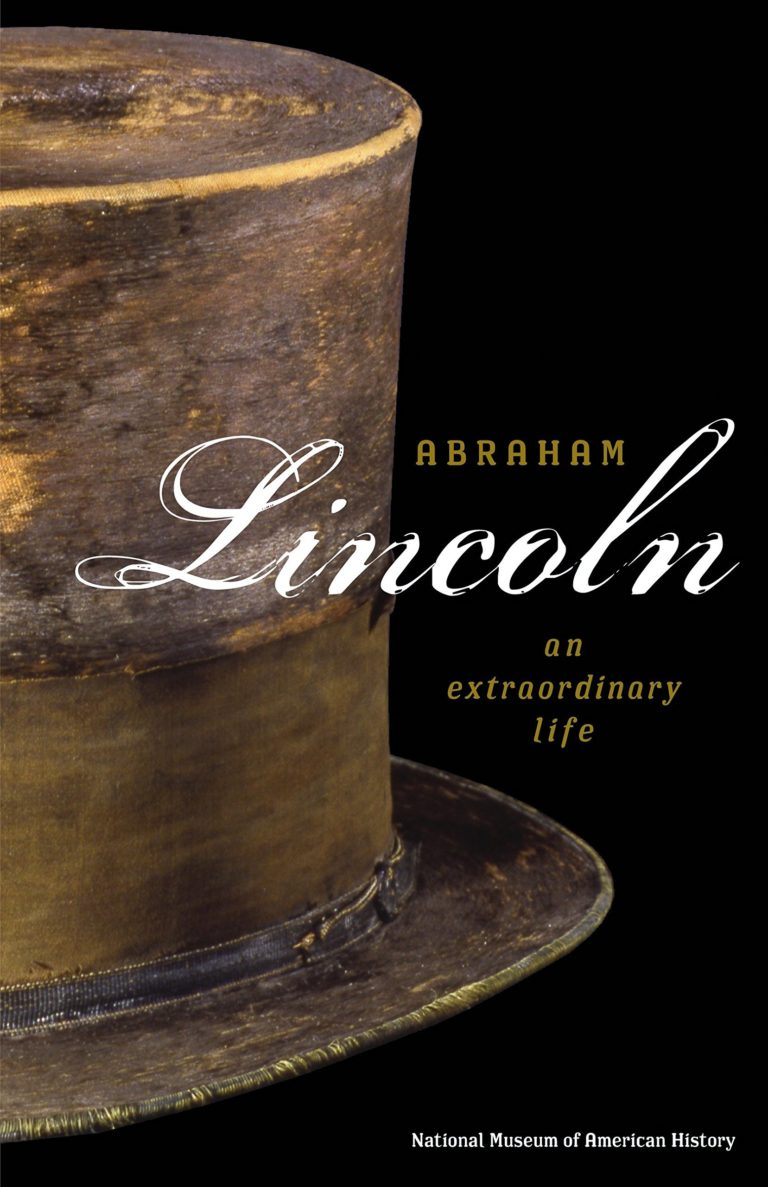

That death awaits next door. A sharp corner separates the two exhibits, and when a visitor steps across the small atrium into the memorial to Lincoln, her first impression is of darkness. The walls of Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life are draped in black, the lighting is targeted, the mood somber. This is a chapel as much as it is a museum, and we are to pay respects as much as we are to learn. And visitors respond; they speak quietly, and move slowly, and linger. The cheerful chaos of The American Presidency is absent here; while that exhibit lays largely open, allowing visitors to move as they will through its rooms, the Lincoln exhibit is a single, sometimes tight corridor snaking inexorably through Lincoln’s life. The narrative pace is well known and essential, and almost liturgical; we accept the irresistible slow progress from the stumpy fields of Kentucky to the White House to Ford’s Theatre. There are no buttons to push, no podiums to play with, only artifacts to ponder and words on the walls to read.

The items here exhibited, particularly in the early sections of the exhibit, tend toward the iconographic—single pieces, instantly recognizable and pieced into the great arc of Lincoln symbology, displayed and lit in solitary cases, separated by appropriately solemn swaths of the black back wall. Upon entering, visitors are greeted with the battered top hat Lincoln wore to Ford’s Theatre, followed in quick succession with a wedge Lincoln used to split rails, a rail which Lincoln split (presumably with the wedge next door), and the “mud circuit” desk the young lawyer sat at while serving the frontier courts of Illinois. We are told that Everett Dirksen, a Republican senator from the state in the 1960s, owned the desk and worked on civil rights legislation while seated at it; thus does the Lincoln legacy persist. The exhibit does here hold a few surprises. We’re shown, for instance, an 1848 sketch and model for an invention designed to lift boats out of shallow water for which Lincoln sought patent protection; this is helpfully contextualized in the industrious Jacksonian era, and in the faith in commerce and support for canal building that Lincoln’s Whig politics embraced.

Lincoln’s rise to the presidency—indeed, his life before the Civil War generally—is quickly but skillfully sketched over in a few exhibit cases. We’re shown a presidential suit, a shawl that he used to keep warm while working in his cold office, an inkwell; surprisingly intimate items that draw us into his life. Campaign memorabilia emphasizes the divided Republican party—an emerging theme in the Lincoln narrative, driven by Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. It also emphasizes the popular support for the lawyer from Illinois: even as the exhibit’s captions emphasize that Lincoln’s frontier image was carefully constructed, the artifacts present him, almost constantly, as a man of the people.

This is driven home when the visitor reaches the first item documenting the war: sheet music, produced in Philadelphia in 1862, for a tune called “We Are Coming, Father Abraham: Three Hundred Thousand More”—a rousing cry that almost immediately, only inches away, crashes into stark, large photographs of the battlefields of Antietam and Gettysburg, and a ceremonial rifle that one imagines Lincoln received from the New Haven Arms Company with mixed emotions.

Essential to Lincoln’s image, and perhaps unique to him among eternally optimistic American heroes, is a sense of tragedy. His triumphs are seasoned with martyrdom, his achievements with melancholy. With one exception, the exhibit handles the assassination with elliptical delicacy, showing us only heartbreaking snatches: a coffee cup which a White House servant retrieved from the president’s windowsill after Lincoln left for Ford’s theatre; the blood-dotted cuff of Laura Keene, lead actress at Ford’s that night; the surgical instruments used on Lincoln’s body. Many visitors round the corner from these fascinating trinkets and gasp upon seeing what comes next, strategically placed over mannequin heads: the hoods placed upon the nine conspirators as they stepped to the platform with nooses around their necks. It’s a rather shocking moment in an intentionally muted exhibit.

We trust that Lincoln had to suffer so the nation could survive; we’ve been told that over and over already. What is novel about Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life is its determined effort to place emancipation at the center of this achievement. Indeed, the exhibit’s tribute to emancipation sits at the literal center of the exhibit, a small atrium that bridges the two halves of the story of Lincoln’s life both spatially and metaphorically. Only here are there benches; only here is there any hint of the technology that The American Presidency relies on: a video, in which notables from scholar Ira Berlin to former president Bill Clinton discuss the social, political, and economic transformations that emancipation wrought. We are shown recruitment posters from the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments, emphasizing that African Americans helped take control of the emancipation process, fighting for their own freedom, an inkstand Lincoln may have used to write the Emancipation Proclamation, and its complete text in an 1864 print. Though the exhibit emphasizes Lincoln’s martyrdom, they are linked, hand in hand, with his accomplishments.

Visitors depart the exhibit past a row of photographs of Lincoln, from the earliest 1840s daguerreotypes to the last cracked and gaunt image captured only weeks before his death. The president’s aging is striking, and telling; we’re to leave with a sense of respect, a sense of debt, and a renewed conviction of the truth of what we believe about Abraham Lincoln.

This article originally appeared in issue 12.2 (January, 2012).