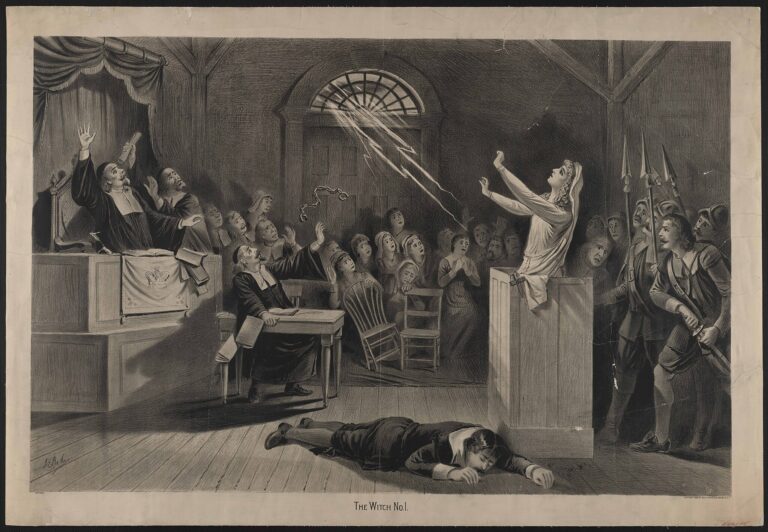

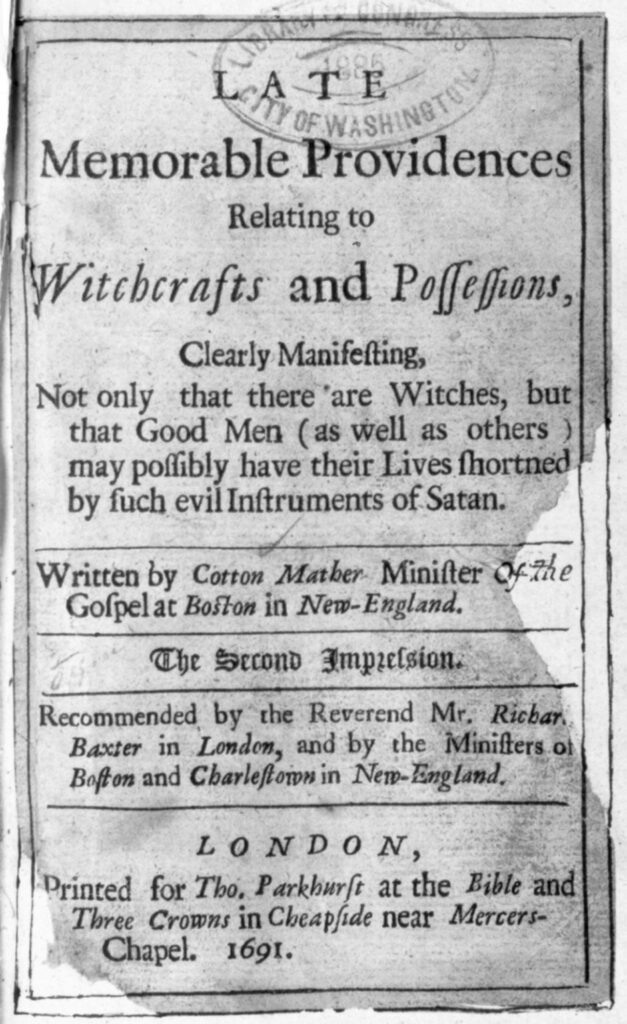

In 1949, freelance writer Marion Starkey pointed out in The Devil in Massachusetts that Samuel Parris owned a copy of Cotton Mather’s Memorable Providences, an account of witchcraft among the Goodwin children in Boston in 1688. Starkey also states that “the Parrises may have also had first-hand experience of the case, since they appear to have been living in Boston at the time.” She suggests that “the little girls might even have been taken [by Parris] to see the hanging.” No professional historian would make such a speculation today, but it is possible that the children in the Parris household overheard the adults talking about witchcraft and the hanging. The execution of Goody Glover on Boston Common in 1688 was the first witchcraft hanging in Boston in over thirty years. Griggs and his family were also in Boston when Dr. Oakes made his “hellish Witchcraft” diagnosis, and Griggs might have become interested. We do not know whether Griggs or Parris attended the hanging, but just knowing about such a remarkable event taking place in the town where they were living may have influenced Parris’s choice of Griggs to make the key diagnosis.

In 1998, Dr. Anthony S. Patton, who was Chief of Thoracic and Vascular Surgery in Salem Hospital for many years, wrote an important biographical sketch of Griggs containing new information about his grand jury work and the state of the medical profession in seventeenth-century New England. As a practicing physician, Patton became interested in Griggs’s medical competence and moral character. He asked the question: Did Griggs simply give a conventional medical diagnosis of the Evil Hand? Or should he have known better and followed the lead of more educated doctors in Boston, such as Thomas Thacher, whose treatments for smallpox and measles were based on the scientific work of the English doctor Thomas Sydenham.

Patton concluded that Griggs was clearly a doctor of his time, practicing like most other New England doctors. Patton also asked whether Griggs “had to know of the possible consequences of his diagnosis.” This question, like those of Upham and Tapley, relies on the benefit of historical hindsight, which Griggs did not have. John Hale emphasizes that Griggs and the other doctors were called in at the first stage of the Salem episode, which concerned only the two girls in Parris’s house: “[The] beginning of which [the Salem case] was very small, and looked on at first as an ordinary case which had fallen out before at several times in other places, and would be quickly over.” It seems clear that Hale saw the outbreak in the Parris house as similar to the small-scale Goodwin case.

On the other hand, Patton notes that Griggs “could have protested or halted his niece’s damaging and continuing testimony against innocent people.” This seems plausible. If Griggs had any misgivings at all, he might have controlled his young grandniece, Elizabeth Hubbard, and stopped her from making dozens of accusations. But the fact that Hubbard often became afflicted in Griggs’s house and, according to the records, at least once in her uncle’s presence, likely strengthened the doctor’s conviction.

Curiously, Griggs played no further role once the legal process began. A search of all 950 digitized court records does not turn up his name in any of the examinations, depositions, or grand jury hearings. But as the new doctor in Salem Village and an acquaintance of Samuel Parris, Griggs may have considered it both responsible and beneficial to assist Parris in this critical moment. Two years later, it is also clear that Griggs had firmly aligned himself with the pro-Parris, pro-witch-hunt faction in the village. He helped Parris’s friend and supporter, Thomas Putnam Jr., in his attempt to contest his stepmother’s will, which gave her large fortune to her son, Putnam’s stepbrother, who was aligned with the anti-Parris, anti-witch-hunt faction.

In placing judgment upon Griggs, it is also useful to consider, as Patton does, the state of the medical profession in New England at the time. There were no medical schools, training programs, or qualifying exams. Training was informal, and men apprenticed themselves to an established doctor and became acquainted with the medical books that described hundreds of herbal treatments for common illnesses. Although Griggs was literate and read medical books, Patton noticed in the documents that he was unable to write and signed his name with a mark.

In 1697, the Massachusetts government decided to accept responsibility for the Salem tragedy and issue a formal apology. A recent series of setbacks in the province—crop failures, a large outbreak of smallpox, and repeated losses in battles against the Native Americans—were believed to have been God’s punishments for the injustice of the Salem trials. The government’s apology, however, was perfunctory and mainly blamed Satan. Samuel Sewall, one of the trial judges, was asked to write it. His statement referred to “Mistakes” that were “fallen into” regarding the “late Tragedie” caused by “Satan and his Instruments, through the awful Judgment of God; He would humble us therefore and pardon all the Errors of his Servants and People that desire to Love his Name.”