The Past Impaneled

The publication of the second volume of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale in 1991 marked more than the completion of Art Spiegelman’s painstakingly researched comic book account of his father’s Holocaust experience and survival. It also marked, at least for those readers who were either unaccustomed to the medium or had relinquished it somewhere during their adolescence, the intellectual legitimization of the comic book. While some of the pictorial conventions used by Spiegelman, particularly his depiction of his characters as animals, left some critics uneasy (misunderstanding the device’s goal of subverting the racist tenets of Nazism), Maus received acclaim as an original and indisputably serious work of history–both in the story it told and in the graphical and textual waysof its telling. (For more reviews and commentaries about Maus, see “Maus Resources on the Web.”)

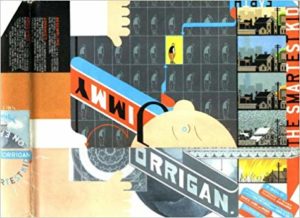

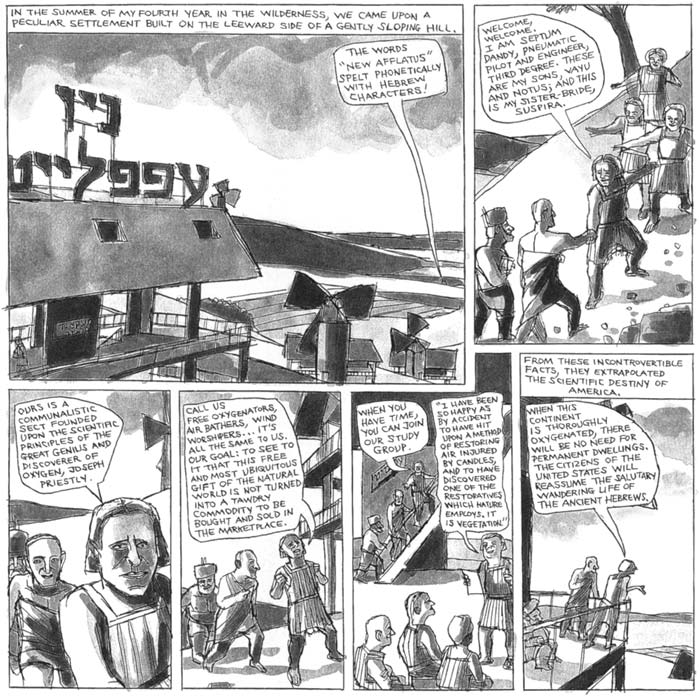

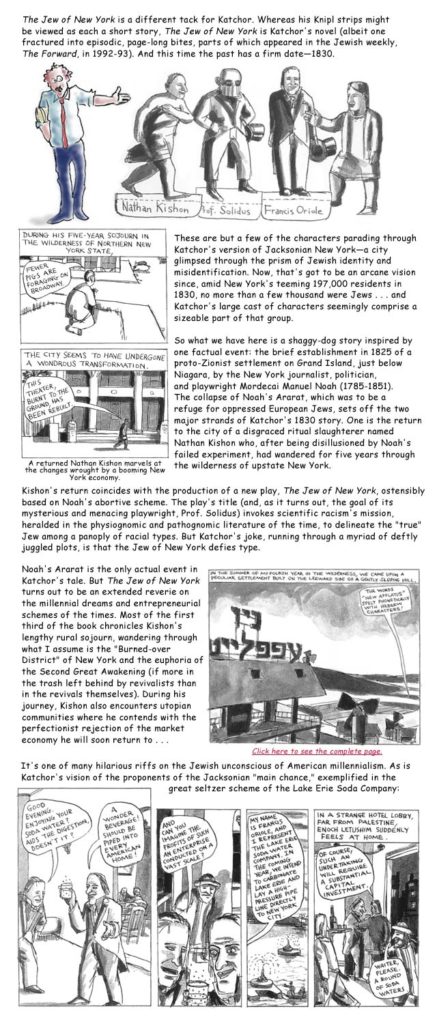

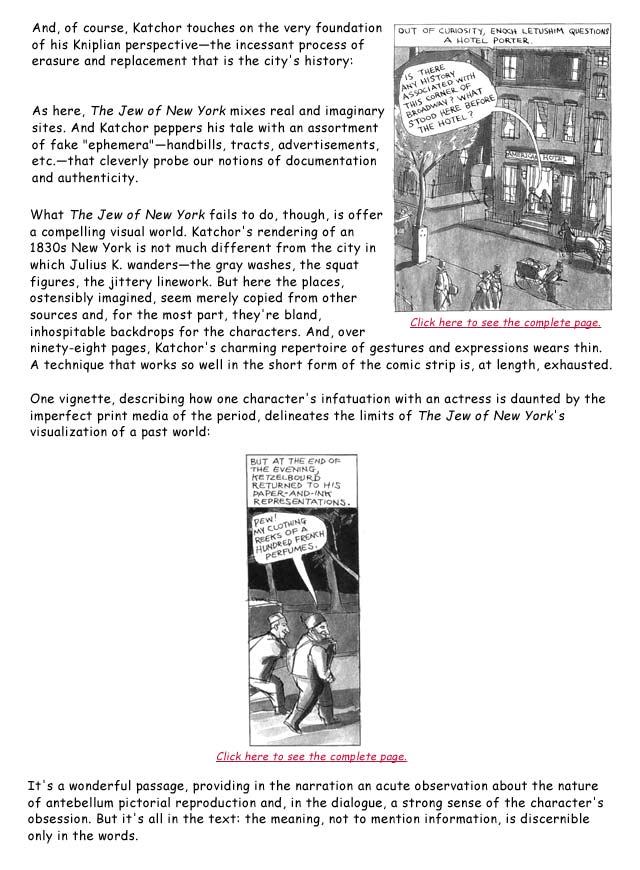

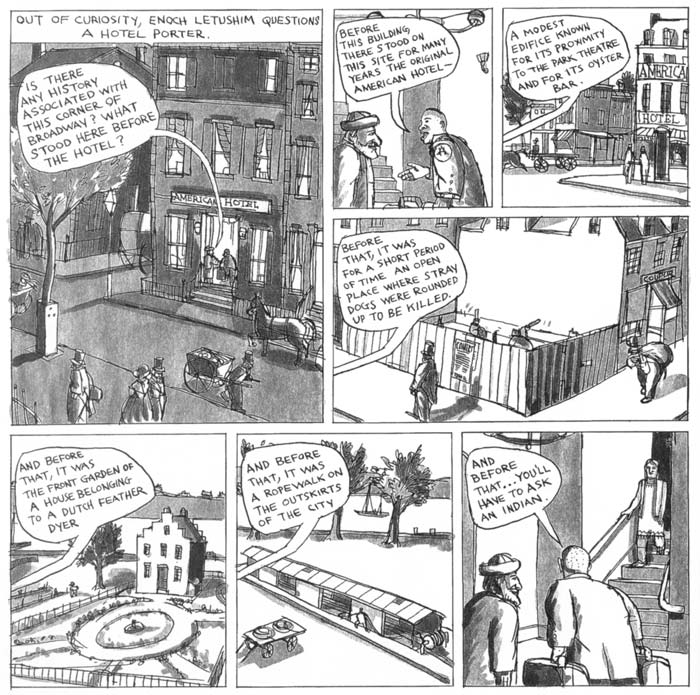

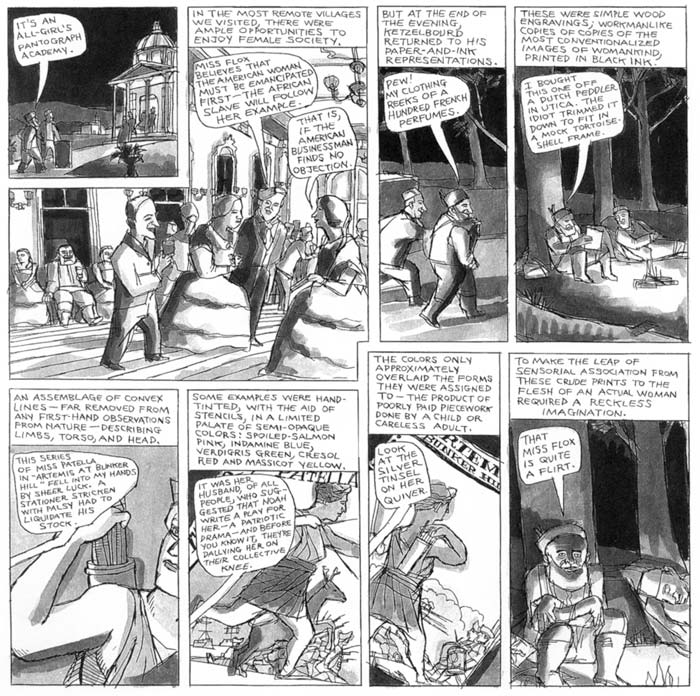

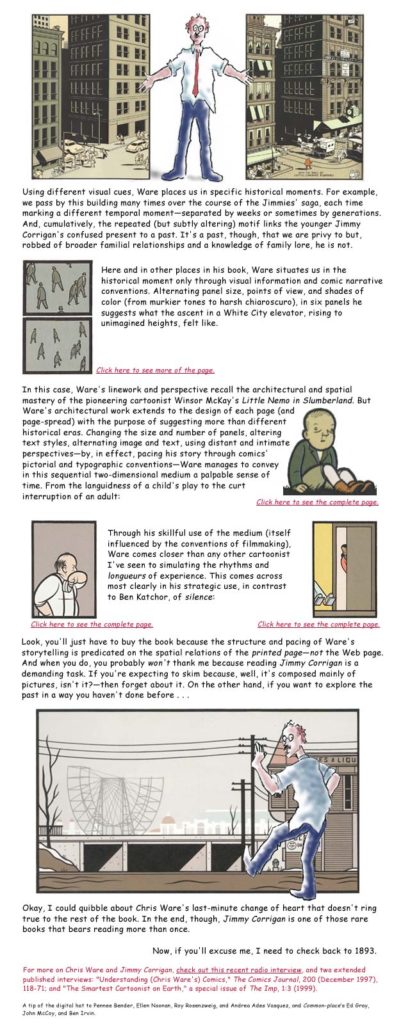

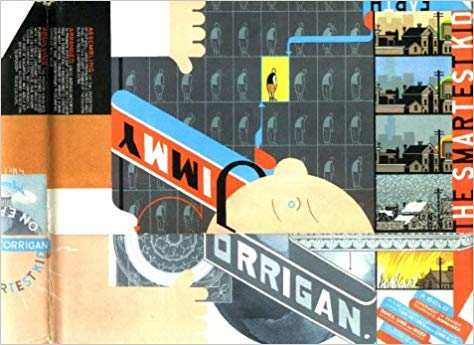

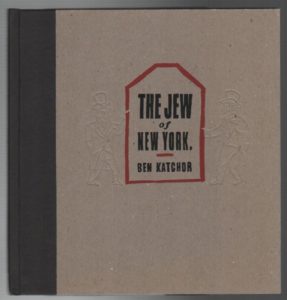

Maus‘s accolades notwithstanding, a certain air of irrespectability still lingers about the comic book as a medium for serious work about the past. Cartoonists such as Larry Gonick, Raymond Briggs, and Joe Sacco have been recognized for the quality of their respective graphical histories, memoirs, and journalism, but the fervent sales and serious critical attention engendered by Maus have not been repeated. Last year, almost a decade after it published Maus, Pantheon released a group of new comic books packaged in formats seemingly designed to belie their actual status: so sumptuous-looking–and expensive–that they

might be construed as art instead of comic books.

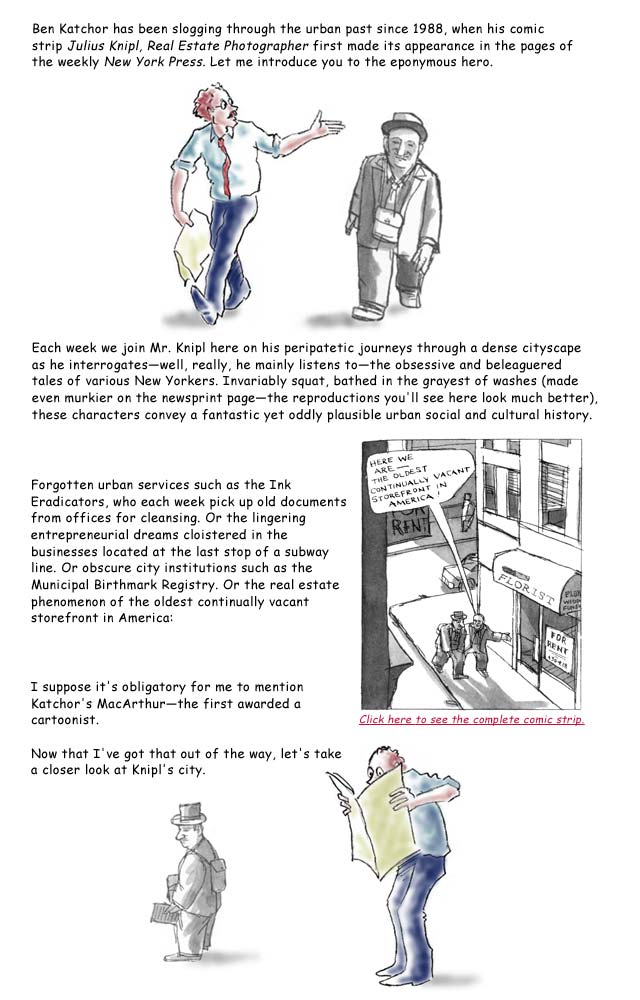

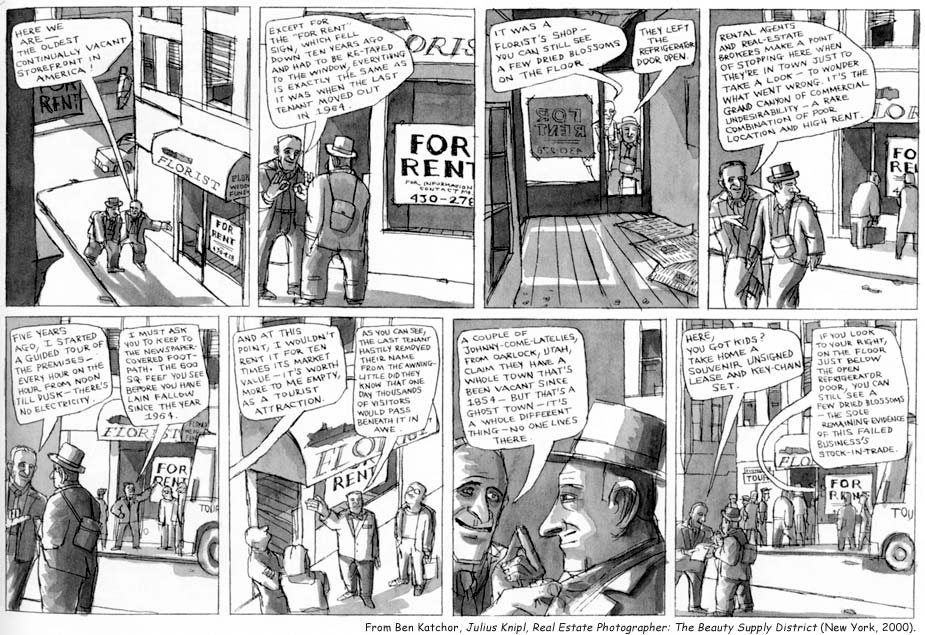

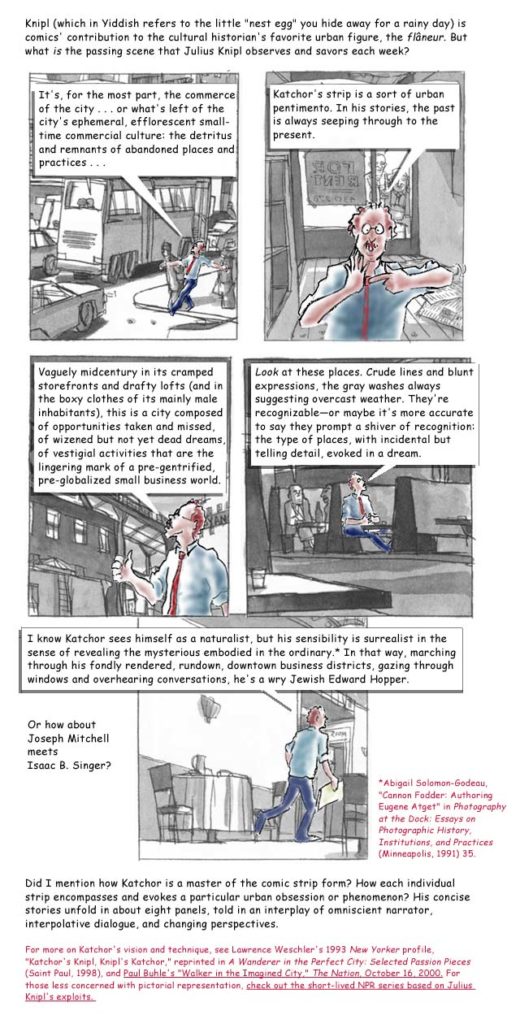

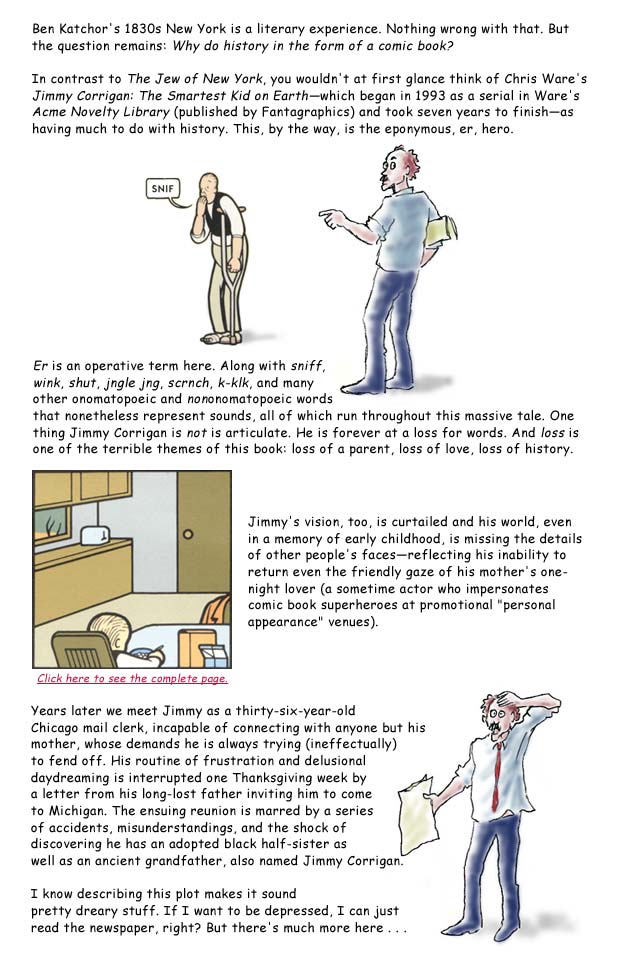

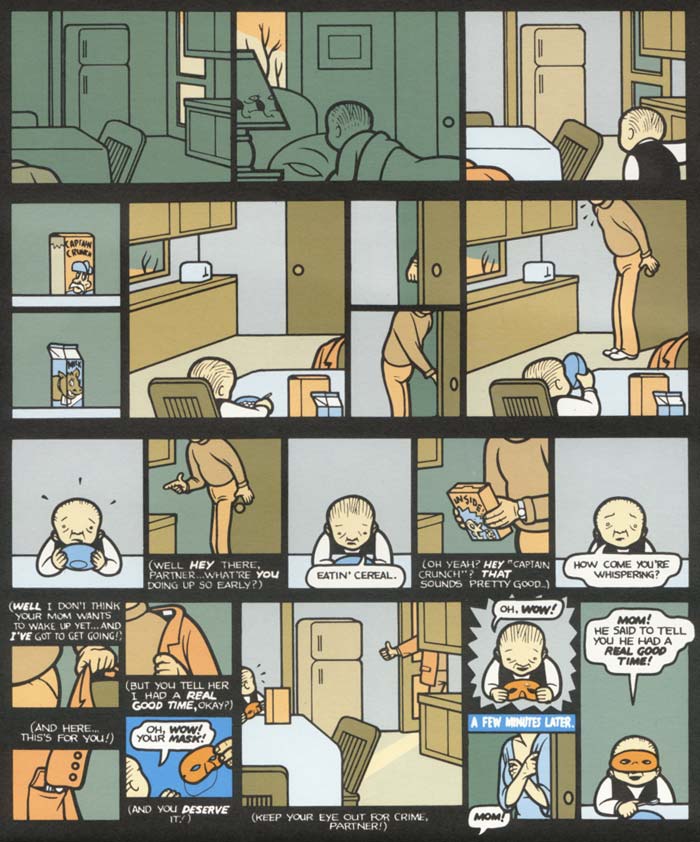

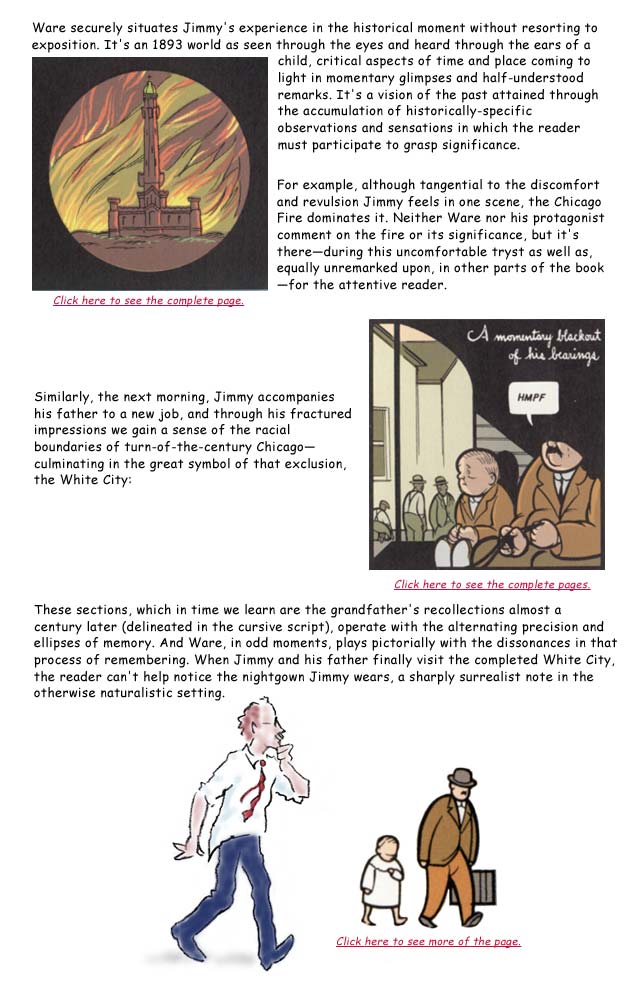

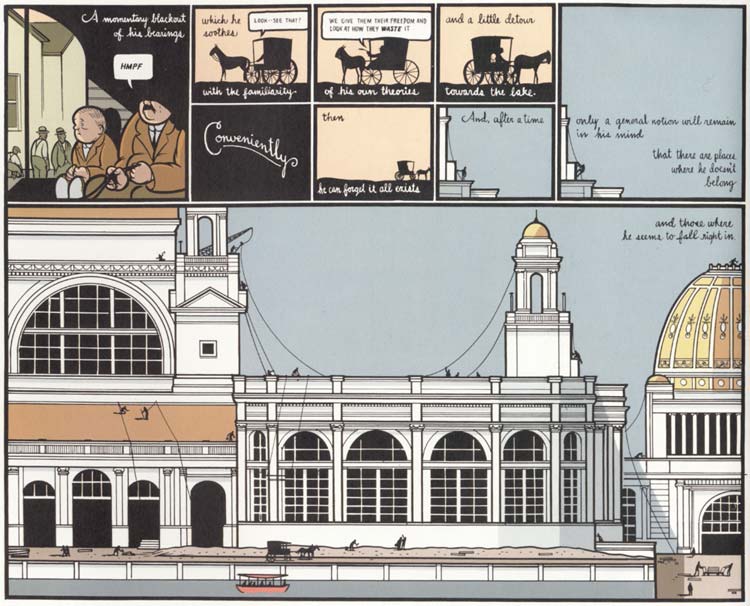

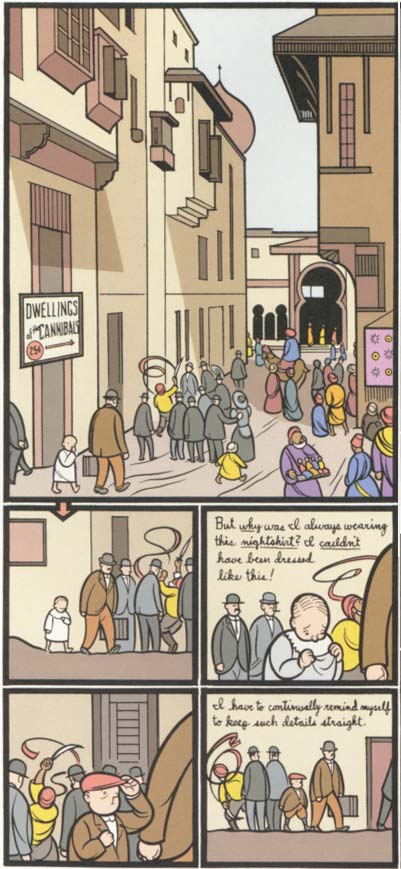

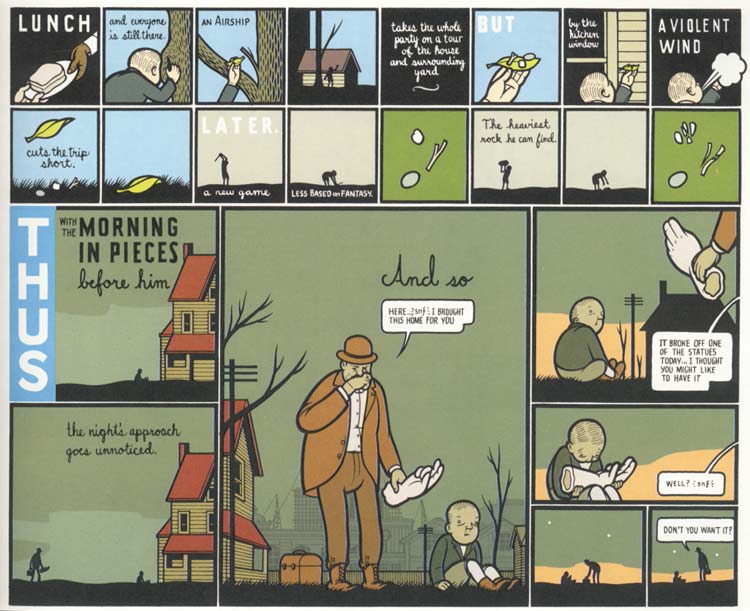

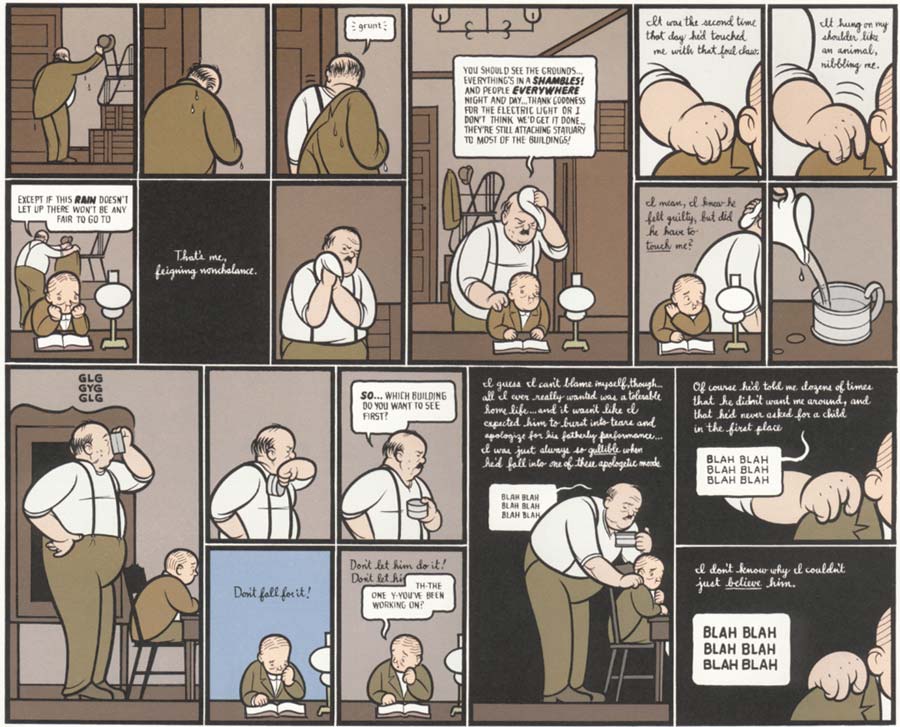

But, while two of these new books–Ben Katchor’s The Jew of New York and Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Boy on Earth–traffic in the past, unlike their predecessor they are works of graphic historical fiction. As such, their publication by a commercial American publisher might be construed as signaling a further maturation of the medium–at least in the sense that they have boldly relinquished the respectable trappings of scholarship, however crude that might at times end up being, in favor of exploring the past in more fantastical terms. But their status as fiction allows us to raise a useful question often overlooked when the pedantic and didactic virtues of “fact” are offered as the primary goal of a work: Why do history in the form of a comic book? Why use this particular medium as opposed to others? What can the comic book offer in the presentation of the past that is unique and compelling?

In the spirit of fantasy–or, at least, fiction–let’s step out of Common-place‘s ordinary mode and into, around, and through these works and their worlds.