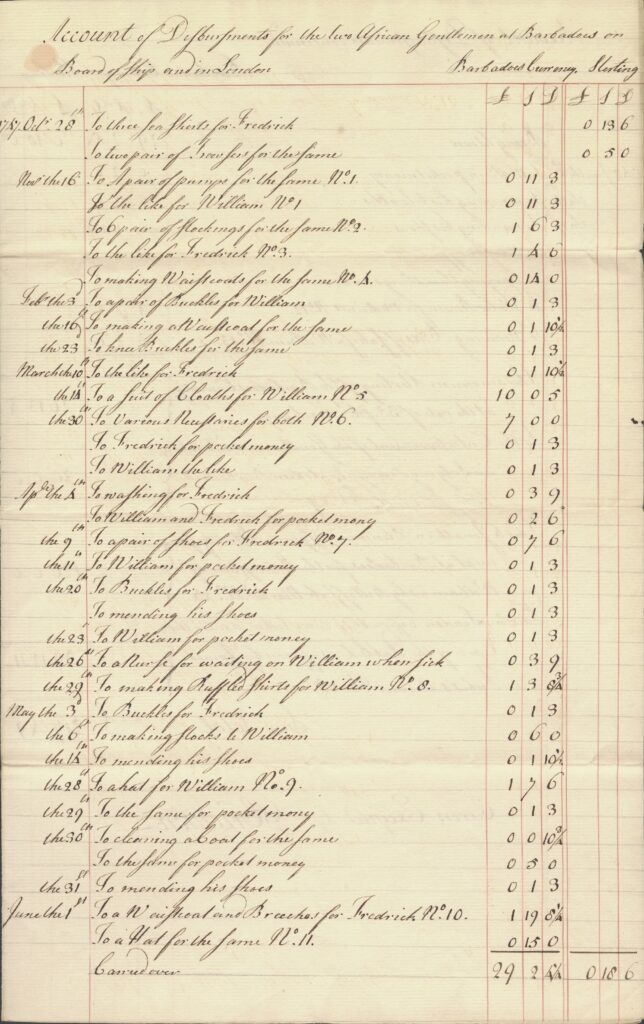

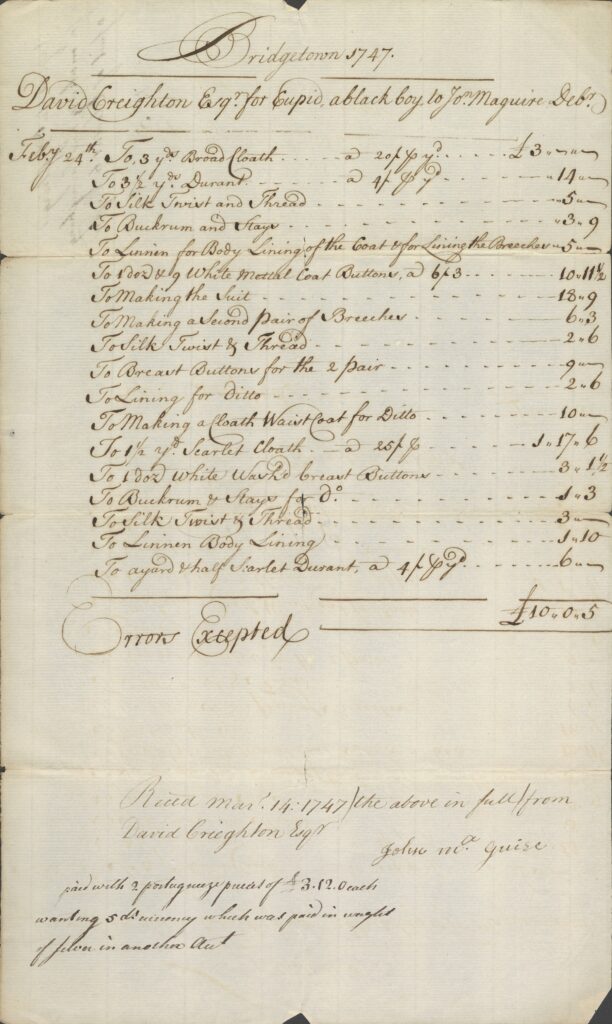

The bill of sale shows that Sessarakoo was formally redeemed on February 11, 1748, by the Royal African Company agent David Crichton for £120. The flurry of financial activity in June 1748 suggests this may have been close to when Sessarakoo and Frederick departed Barbados for England, as Crichton finalized plans and closed accounts. Receipts for lodging and clothing appeared again in England in August 1748, giving us a firmer date of their arrival. It was also previously unclear who Sessarakoo’s companion was, but the repeated presence of Frederick in these financial documents provides us with at least a first name. This clutch of documents in Charles Townshend’s papers, then, gives us a much clearer timeline of events, names of individuals involved, and potential for future research to more fully tell William Ansah Sessarakoo’s story while in Barbados. They also give us another window into just how entwined stories of human enslavement are to the histories of British empire, finances, and politics. Perhaps finding Sessarakoo and Townshend in conversation shouldn’t have felt as surprising as it was.

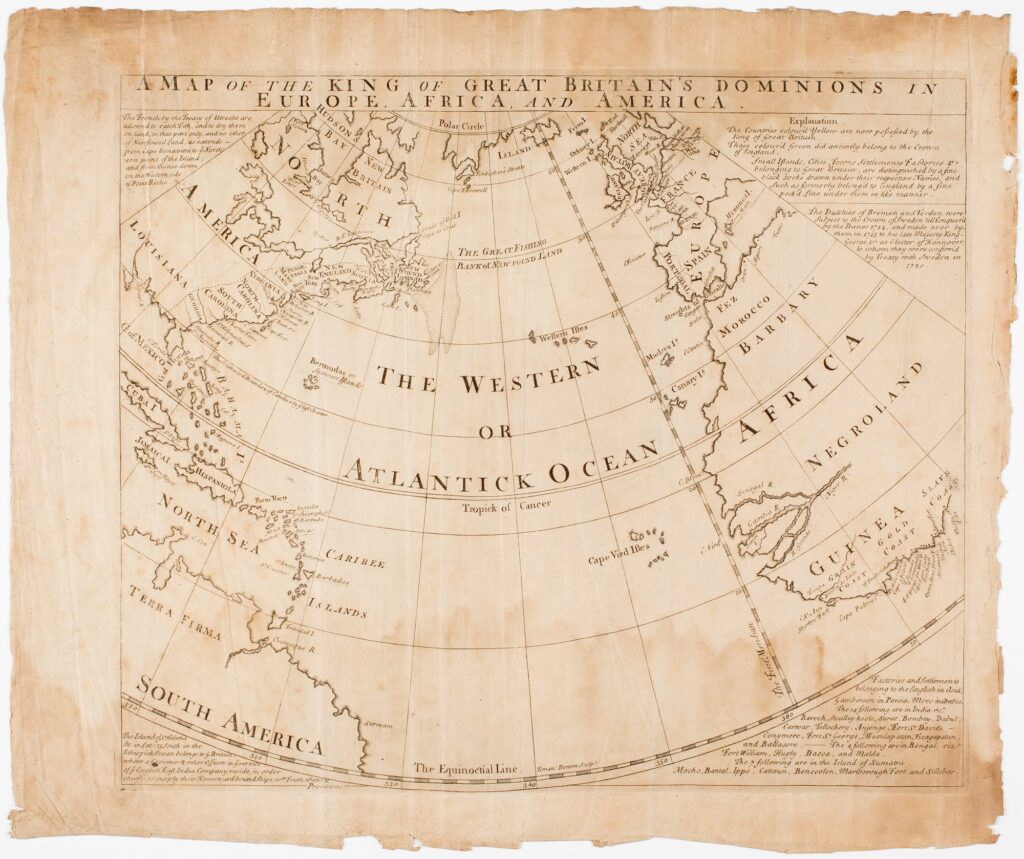

Indeed, by 1752, the Board of Trade put forth a memorial about rebuilding the fort at Anomabo, with the consent and aid of Eno Baise Kurentsi. They consulted a committee of merchants who asserted that “they considered Annamaboe as the Key to the whole Trade of the Gold Coast.” They conferred with David Crichton, “formerly Chief Agent for the old Company at Cape Coast Castle, and a Person well acquainted with the Situation and Circumstance of the Place.” The Board ultimately agreed to recommend the fort’s construction, because it would “tend to promote Trade—by serving the Friendship and Assistance of John Corrantee and his Family, upon which this Trade so greatly Depends.” On that committee sat Charles Townshend, who likely knew all too well the particular details of what it took to secure the friendship of the Corrantee family. And now, thanks to his papers, so do we.

The finding aid for the Charles Townshend Papers at the William L. Clements Library has been updated to include an explicit statement about the documents relating to William Ansah Sessarakoo, in the hopes they draw more researchers to them. Scans of this material are provided in the Further Reading section to encourage further study.

Further Reading:

“Mr. Crichton’s Papers,” Charles Townshend Papers, Box 15, Folders 21-36, William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan. (View Scans)

“An act for extending and improving the trade to Africa,” in Danby Pickering, The Statutes at Large, from the 23d to the 26th Year of King George II. Vol. 20. Cambridge: Joseph Bentham, 1765.

“Blenman of Barbados,” in Vere Langford Oliver, Caribbeana: Being Miscellaneous Papers Relating to the History, Genealogy, Topography, and Antiquities of the British West Indies, Vol. 5 (London: Mitchell, Hughes & Clark, 1919): 153-155.

Rob S. Cox and Shannon Wait, “Finding Aid for the Charles Townshend Papers,” William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan, Accessed November 8, 2024. https://findingaids.lib.umich.edu/catalog/umich-wcl-M-1773tow

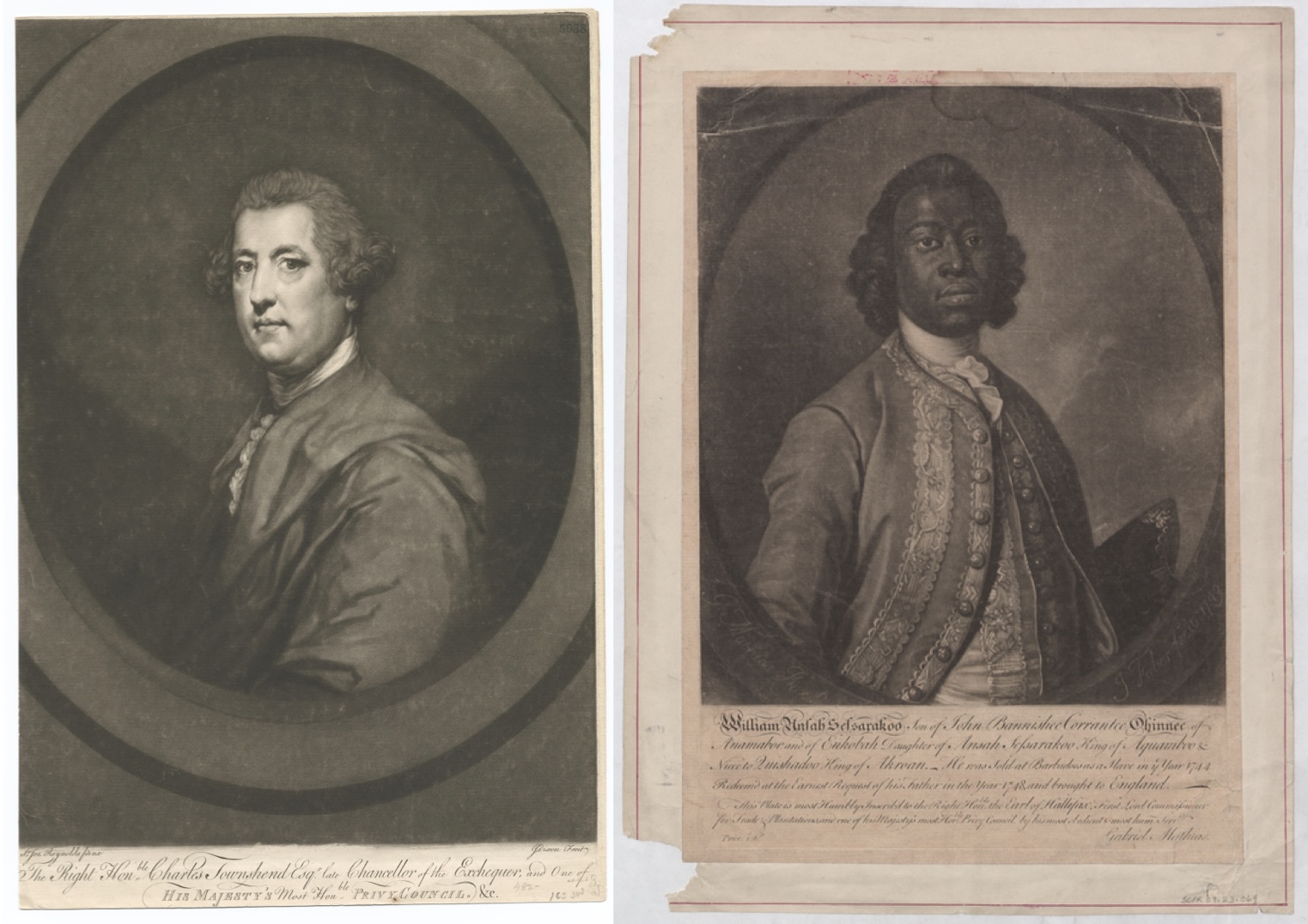

John Faber, eng., after Gabriel Mathias, “William Ansah Sessarakoo,” ([London]: [mid-18th century]), National Portrait Gallery, London, Accessed November 8, 2024. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw13960/William-Ansah-Sessarakoo

Ruth A. Fisher, “Extracts from the Records of the African Companies [Part 3],” The Journal of Negro History 13, no. 3 (July 1928): 343-367.

Ruth A. Fisher, “Extracts from the Records of the African Companies [Part 4],” The Journal of Negro History 13, no. 3 (July 1928): 367-394.

Ryan Hanley, “The Royal Slave: Nobility, Diplomacy and the ‘African Prince’ in Britain, 1748-1752,” Itinerario 39, no. 2 (2015): 329-47.

Journal of the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations From January 1749-50 to December 1753 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1932): 260.

Gabriel Matthias, Portrait of William Ansah Sessarakoo, son of Eno Baisie Kurentsi (John Currantee) of Anomabu, Oil on canvas, 1749. The Menil Collection.

The Royal African: Or, Memoirs of the Young Prince of Annamaboe (London: W. Reeve, 1749).

SlaveVoyages, Voyage ID 94787. Accessed November 8, 2024. www.slavevoyages.org

- D. Smith, Slavery, Family, and Gentry Capitalism in the British Atlantic: The World of the Lascelles, 1648–1834 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Randy J. Sparks, Where the Negroes are Masters: An African Port in the Era of the Slave Trade (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014).

“A Young African Prince Sold for a Slave,” The Gentleman’s Magazine, 19 (February 1749): 89-90.

This article originally appeared in June 2025.

Jayne Ptolemy received her Ph.D. in African American Studies and History from Yale University in 2013. She has since worked in various roles at the William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan, where she currently serves as the Associate Curator of Manuscripts.