The Refugee’s Revenge

Part I

On August 3, 1692, Elizur Keysar of Salem Town testified before the grand jury considering possible indictments of the Reverend George Burroughs of Wells, Maine, for witchcraft. Keysar, who believed that Burroughs was “the Cheife of all the persons accused for witchcraft, or the Ring Leader of them all,” described a “diabolicall apperition” he and his maidservant had seen on the evening of May 5, after he had conversed uneasily with Burroughs in a tavern then serving as the clergyman’s makeshift prison. Back in an unlighted room in his own house, Keysar told the grand jury, “I did see very strange things appeare in the Chimney, I suppose a dozen of them, which seemed to mee to be something like Jelly that used to be in the water, and quaver with a strainge Motion, and then quickly disappeared.” Next he saw a light up the chimney “aboute the bigness of my hand . . . which quivered & shaked.” As Keysar completed his statement to the jurors, another witness offered an unusual interjection. In the words of a court clerk, “Mercy Lewis also said that Mr Borroughs told her that he made lights in Mr Keyzers chimny.” (The crucial words “told her that” exist in a manuscript copy of the deposition only; they were omitted when the witchcraft documents were transcribed for publication.)

Mercy Lewis’s own sworn testimony to the grand jury that day disclosed that she “very well knew” George Burroughs; indeed, she indicated that she had lived with Burroughs and his family, surely as a maidservant, at some point in the past. Burroughs’s specter, she declared, had appeared to her twice in early May, torturing her and insisting that she sign a “new fashon book,” which he claimed she must have previously seen in his study. Mercy, though, refused the request, recognizing the volume as the devil’s book. She also reported that the malefic cleric had confessed bewitching other people and recruiting a Topsfield teenager, Abigail Hobbs, into the ranks of the witches.

In the oft-told tale of the Salem witchcraft trials, neither the nineteen-year-old maidservant Mercy Lewis nor her former master usually receives much attention. Abigail Williams, the eleven-year-old niece of the Reverend Samuel Parris (the Village pastor), and Ann Putnam Jr., the twelve-year-old daughter of a prominent Village family, have seemed to scholars and popularizers alike the most important of the afflicted accusers. Likewise, historians have concentrated on the large number of women charged with witchcraft, rather than the smaller though still substantial number of men so accused. Yet Elizur Keysar was just one of many contemporaries who thought that George Burroughs was the “Ring Leader” of the witches. So vast a conspiracy, many New Englanders concluded, could not be led by women. The witches’ most likely master was, instead, a minister, a well-educated man who could subvert God’s church from within.

And one of those best situated to uncover that man’s alliance with the devil was someone who “very well knew” him and had once lived with his family, maidservant though she was. Mercy Lewis’s addition to Elizar Keysar’s grand-jury testimony revealed her extraordinary eagerness to support the charges against her former master. In only a bare handful of other instances are similar unsolicited interjections preserved in the Salem records.

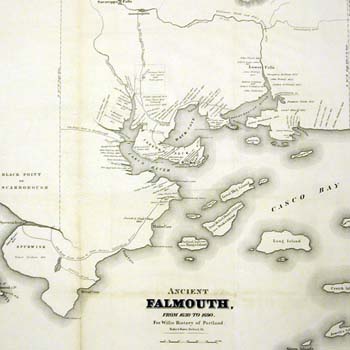

Who was Mercy Lewis, and why did she hate George Burroughs? And who, for that matter, was Burroughs? Both have primarily been known as residents of Salem Village–Lewis as the servant of Thomas and Ann Carr Putnam, parents of the afflicted Ann Jr., and Burroughs as a one-time and angrily dismissed pastor of the Village church. But in fact, Lewis and Burroughs knew each other so well not in the Village but in another time and place: in the 1670s and 1680s in the little town of Falmouth (now Portland), located on Casco Bay, Maine.

Mercy was born there about 1673. Her grandfather George Lewis had brought his wife and three children to Maine from England in the mid-1640s; four more children–including her father Philip–were born in America. For a time in the 1660s Philip Lewis lived on Hog Island in the bay, superintending the livestock herds of the Falmouth community, but whether his daughter Mercy was born on that island is unknown. In the mid-1670s, all Philip’s siblings and his parents owned farms in the Casco region.

George Burroughs, who was born in Virginia but raised in Roxbury, Massachusetts, attended Harvard as a member of the class of 1670. In 1674, when Mercy was still an infant, he moved his new wife and young child from Roxbury to Casco, where he began to minister to the small congregation of settlers, including the many members of the extended Lewis clan. Neither then nor later did Burroughs achieve ordination as the leader of a formally organized Puritan congregation. Consequently, at no time during his pastoral career could he baptize babies or administer the sacraments, although he could both preach and instruct children in religious precepts. In fact, he probably taught Mercy Lewis, who knew her Bible well.

Suspicions of Burroughs first surfaced in mid-April 1692, after Abigail Hobbs confessed that the devil had recruited her as a witch about four years earlier while her family, too, was living in Falmouth. Abigail did not initially name the minister as Satan’s agent, but about thirty-six hours after her confession, Ann Putnam Jr. did.

Thomas Putnam reported to the Salem magistrates, John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin, that on the evening of April 20 his daughter “was greviously [sic] affrighted and cried out oh dreadfull: dreadfull here is a minister com[e]: what are Ministers witches to[o]”? The specter tortured Ann while she carried on a dialogue with him. “It was a dreadfull thing,” she told the apparition, “that he which was a Minister that should teach children to feare God should com[e] to persuad[e] poor creatures to give their souls to the divill.” After repeatedly refusing to tell her who he was, the specter finally revealed his identity: “[H]e tould me that his name was George Burroughs and that he had had three wives: and that he had bewitched the Two first of them to death: and that he kiled . . . Mr Lawsons child because he went to the eastward with Sir Edmon and preached soe: to the souldiers and that he had bewitched a grate many souldiers to death at the eastward, when Sir Edmon was their [sic]. and that he had made Abigail Hobbs a witch and: severall witches more.” During the day on April 21, Abigail Williams also saw the specter of George Burroughs and conversed with it, but her vision lacked those elements of Ann’s that referred to “the eastward,” or Maine, nor did she mention Burroughs’s role as a teacher of children. Those omissions suggest that Ann Jr., but not Parris’s niece, had been talking to someone who knew the clergyman as a religious instructor, and who also knew a great deal about recent events in Maine–talking, in short, to the Putnams’ servant, Mercy Lewis.

What had happened “at the eastward,” and what valence did those events retain in Salem? The references in Ann Jr.’s vision cannot be understood without a brief discussion of happenings on the Maine frontier during the preceding four years. “Sir Edmon” was Sir Edmund Andros, the governor of the Dominion of New England from 1686 until he was ousted in the Massachusetts phase of the Glorious Revolution in April 1689. During the winter of 1688-89, Andros led a large militia force to Pemaquid, northeast of Casco Bay, in an attempt to quash a burgeoning conflict between the Wabanaki Indians and English settlers that had begun the previous August. Andros failed; and by 1692 Wabanaki victories in the struggle that has become known as King William’s War (called the Second Indian War in Maine) had led to the abandonment of Falmouth and all the other Anglo-American settlements north of Wells.

The “Mr. Lawson” whose child Burroughs had reputedly killed was the Reverend Deodat Lawson, Burroughs’s immediate successor as minister in Salem Village. Lawson had served as the chaplain to Andros’s troops at Pemaquid; his first wife and child both died at about that time (evidently during his absence). Others too later repeated Ann’s charge that Burroughs had bewitched them.

But why were these matters relevant to the charge that George Burroughs was a witch, and what, other than the fact that she had once been his servant, caused Mercy Lewis’s animus against George Burroughs?

To answer those questions it is necessary to go back nearly two decades, to the moment when the lives of a little girl and a young minister first began to intertwine.

In August 1676, the three-year-old Mercy Lewis and the twenty-three-year-old George Burroughs were both living in Falmouth, when their world suddenly collapsed around them. The previous fall, violent clashes had erupted between English settlers and the Wabanakis, all of whom had until that time lived in relative peace, engaging in trade that benefited everyone. (In southern New England, related hostilities were known as King Philip’s War; Maine residents eventually called it the First Indian War.)

On Wednesday, August 9, some Wabanakis killed a cow belonging to Captain Anthony Brackett. An Indian named Simon, who had been hanging around Brackett’s farm for several weeks, said he would find the culprits. Early on Friday morning the eleventh, Simon returned with the men responsible for the killing. They invaded Brackett’s house, took his weapons, and asked him “whether he had rather serve the Indians, or be slain by them.” Faced with that choice, Brackett surrendered, along with his wife and children. But his brother-in-law tried to resist and was killed.

The Indians moved through the area called Back Cove, striking one farm after another on the mainland north of the peninsula on which the town of Falmouth was situated. At Robert Corbin’s, they surprised him and his brother-in-law Benjamin Atwell while they were haying in the fields, killing both men and capturing their wives and several children. They next slew James Ross and his wife, taking some of their children captive. Two men traveling by canoe managed to warn the town, but the numbers killed and captured mounted as the day wore on. Mercy’s parents escaped with her to an island in the bay, along with George Burroughs and others, but her father’s extended family was hard hit. The dead men Benjamin Atwell and James Ross were her uncles by marriage, the captured Alice Atwell and the dead Ann Ross her father’s sisters. Her paternal grandparents numbered among those slain. Many of her young cousins were killed or captured, including all but one of the children of another of her father’s sisters, Mary Lewis Skilling. One more uncle and his wife died later in the war.

Altogether, wrote a survivor five days later, eleven men died and twenty-three women and children were killed or captured at Casco on August 11. “We that are alive are forced upon Mr. Andrews his Island to secure our own and the lives of our families[.] we have but little provision and are so few in number that we are not able to bury the dead till more strength come to us,” he told his mother-in-law in Boston, pleading for assistance of any sort. The help the refugees received permitted them to leave. Mercy and her parents probably moved temporarily to Salem Town, where her uncle by marriage Thomas Skilling died a few months later, possibly from a wound suffered in the attack. A treaty ended the war in 1678, and former residents thereafter slowly filtered back to Falmouth and the other towns abandoned in 1676. By 1683, the Lewises had returned to rebuild their lives in Casco Bay. Mercy was then ten years old.

Part II

That same year, George Burroughs, too, returned to Falmouth. While the Lewises had been sheltered in Salem Town, he had lived first in Salisbury (then the home of Ann Carr, prior to her marriage to Thomas Putnam) and later, from late 1680 to the spring of 1683, in Salem Village. In Salisbury, Burroughs witnessed, and almost certainly took sides in, an acrimonious dispute that divided the town’s minister, the elderly John Wheelwright, and Major Robert Pike, its magistrate and militia leader. The town split into two factions; Ann Carr’s family sided with Pike, whereas Burroughs, who served briefly as Wheelwright’s assistant and occupied the town pulpit for a time after the minister’s death in November 1679, in all likelihood supported the aged clergyman.

If Burroughs ever had thoughts of succeeding Wheelwright as the leader of the Salisbury congregation, the affray (and perhaps his role in it) would have rendered that unlikely, if not altogether impossible. Accordingly, George Burroughs had to look elsewhere; and so too at the same time did Salem Village, following the less-than-amicable departure of Lawson, its first minister. The Village hired Burroughs in late 1680, but his tenure there was both brief and unpleasant. By the summer of 1682, dissatisfied Villagers were refusing to pay his salary. In early March 1683, Burroughs moved his family back to the recently reoccupied Falmouth, which was protected by Fort Loyal, newly constructed to help defend the region.

To advance the resettlement efforts, Falmouth took possession of 170 of 200 acres previously granted to Burroughs, for his property was close to the new town center. The remaining thirty acres of his original holding, which lay approximately half a mile west of the new fort, were confirmed to him. Later that year, he exchanged seven acres of his land for John Skilling’s house and lot, conveniently located near the meetinghouse, which was sited to the east of the fort. John Skilling’s dead brother Thomas had been Mercy Lewis’s uncle by marriage. Philip Lewis’s own house lot in the resettled community, where Mercy lived, lay approximately a quarter mile west of the fort and thus less than half a mile from Burroughs’s new dwelling.

Philip Lewis’s town lot lay near Joseph Ingersoll’s. And here Abigail Hobbs reenters my narrative. In her 1692 confession, Abigail indicated that she knew Joseph Ingersoll’s maidservant “very well” during her residence in Falmouth. Accordingly, the Hobbs family (which seems to have rented property there between 1683 and 1689), probably lived in close proximity to Ingersoll and thus to the Lewis household, which was situated on a neighboring lot. Mercy Lewis and Abigail Hobbs (who was five years younger) would have seen each other regularly in Falmouth village. Another quarter-mile west of their homes lay Burroughs’s remaining twenty-three acres. Since he undoubtedly farmed or cut wood on that land, the clergyman would have passed the Lewis and Hobbs households as he moved between his house (to the east of Fort Loyal) and his land on the west side of town. Thus in Falmouth George Burroughs, Mercy Lewis, and Abigail Hobbs must have seen each other frequently in the mid-1680’s, perhaps even daily.

The lives of all three people changed dramatically after a second Wabanaki attack on Falmouth, which occurred on September 21, 1689, during the Second Indian War. This time the English settlers received a timely warning of the impending assault, and Boston authorities reinforced Fort Loyal with a sizable contingent of militiamen under the command of the elderly, experienced Benjamin Church, who had achieved fame during King Philip’s War. Sylvanus Davis, the fort’s commander, later reported “a fierce fight” lasting about six hours, in which the New Englanders “forced them to Retreate & Judge many of them to bee slaine . . . there was Grate firings on Both sides.” The English lost eleven soldiers killed and ten wounded, some of whom died later. How many townspeople were among the casualties went unrecorded; they might have included Mercy Lewis’s parents (her father is last known to have been alive in April 1689). But the Reverend George Burroughs again survived the attack; on September 22 Church declared himself “well Satisfied with” Burroughs, who had been “present with us yesterday in the fight.”

In the aftermath of the battle, the Hobbs family returned to Topsfield, whence they had come, and the by-then orphaned Mercy Lewis moved in with George Burroughs, almost certainly as his servant. Since her father and his extended family had owned a great deal of land prior to August 1676, her new dependent status must have been a shock. How long she lived with his family is unknown, but it was probably no more than a few months. When Burroughs, seeking a safer place to live, moved south to Wells some time during the winter of 1689-90, Mercy seems to have gone to Beverly, again as a servant. After about nine months there, she moved on to Salem Village, where her recently married sister lived, and where she was yet again hired out, this time to the Putnams.

Consequently, none of these former residents of Falmouth–neither Burroughs, Hobbs, nor Lewis–was present when the Wabanakis launched their third, and most devastating, attack on the little settlement in mid-May 1690. After a siege of five days, during which almost all of its male defenders were killed or wounded, Fort Loyal surrendered to a combined force of French and Indians. Promises of quarter were not fulfilled, and most of the two hundred or so survivors were slaughtered on the spot, with a few carried off into captivity by the Wabanakis. Among the dead and captured were three more of Mercy Lewis’s relatives.

Now it is possible to return to Ann Putnam Jr.’s vision of April 20, 1692. Ann Jr.–whose source of information, recall, was Mercy Lewis–charged Burroughs with killing his successor’s child because Deodat Lawson had been hired as chaplain to Andros’s men. But why would Burroughs care? In September 1689 Benjamin Church alluded to a possible reason for the purported malefic act. In his remarks on the minister, he commented that Burroughs “had thoughts of removing” from Falmouth because “his present maintenance from this Town by reason of their poverty, is not enough for his livelihood.” So, Church declared, “I shall Encourage him to Stay promising him an allowance from the publique Treasury for what Service he shall do for the Army.”

That observation suggests a motive for Burroughs’s possible anger about Lawson’s employment with Andros: perhaps he had wanted the job himself. Did Burroughs express jealousy or frustration about Lawson’s chaplaincy in the hearing of Mercy Lewis when she lived in his household? She could later have passed that on to Ann Putnam, who incorporated the information into her spectral vision of the minister.

Burroughs’s specter also told Ann Jr. that “he had bewitched a grate many souldiers to death at the eastward, when Sir Edmon was their [sic].” The malevolent killing of soldiers in Maine during Andros’s campaign could have had only one purpose: assisting the Wabanakis in their war against God’s people. But why would Burroughs do such a thing? And why would that treachery help to reveal his identity as a witch?

New Englanders had long thought of Native Americans as devil worshippers. North America had been “the Devil’s territories,” Cotton Mather later wrote, before the Christian English settlers arrived. That George Burroughs had indeed spectrally allied himself to Satan and the Wabanakis could well have appeared likely to anyone who contemplated his uncanny ability to survive the attacks on Casco in August 1676 and September 1689, followed by his remarkably prescient decision to leave Falmouth sometime in the winter of 1689-90, mere months before the town fell to the Wabanakis in May 1690. And the “anyone” in that sentence was not, of course, just anyone–it was a very specific someone, Mercy Lewis, whose large extended family had essentially been wiped out in the same devastating attacks from which Burroughs had so stunningly and completely escaped.

He was, therefore, a witch. Mercy Lewis knew it because of her experiences on the northeastern frontier, and she, Ann Putnam, Abigail Hobbs, and others said it. They accused Burroughs at his formal examination on May 9, 1692, and they repeated their charges at the grand-jury proceedings on August 3 and at the clergyman’s trial two days later. Much of the testimony offered on August 5 pertained to Maine, and to Burroughs’s role as the witches’ leader. Deodat Lawson, who attended the trial, later recalled that the eight unnamed confessors who testified (almost certainly including Abigail Hobbs) described “some hundreds of the society of witches, considerable companies of whom were affirmed to muster in arms by beat of drum.” Burroughs summoned them to the meetings “from all quarters . . . with the sound of a diabolical trumpet,” and “did administer the sacrament of Satan to them, encouraging them to go on in their way, and they should certainly prevail.”

The confessors’ use of military imagery was not coincidental. People, especially refugees from the Maine frontier, were all too well accustomed to the sounds of trumpets summoning militiamen to battle, and to the sight of forces mustering to oppose the enemy. The wars that had begun in the visible world in 1675 were continuing in 1692 in the form of struggles in the invisible world as well.

The hanging of the Reverend George Burroughs on August 19, 1692, can best be seen, therefore, as the wartime execution of a traitor. Mercy Lewis, the refugee who had lost everything but her life in the war, thereby exacted her revenge.

Months earlier, in mid-April, Ann Putnam Jr. had turned Abigail Hobbs’s confession, which generally described deviltry on the Maine frontier, into a specific accusation of George Burroughs, whom she was too young to have known personally. But Mercy, the family’s maidservant, had undoubtedly filled Ann’s head with tales of the mysterious clergyman she had previously served. The link between the Maine frontier and Salem Village, first identified by Abigail Hobbs and then forged firmly by Mercy Lewis, altered the course of the burgeoning crisis, causing an explosion of accusations outside the confines of Salem Village and spreading witchcraft charges throughout all of Essex County. The event known today simply as “Salem” in reality, then, involved much of northern New England.

Further Reading: The records of the Salem witchcraft trials were transcribed by the WPA in the 1930s and can be found in Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, eds., The Salem Witchcraft Papers: Verbatim Transcripts of the Legal Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Outbreak of 1692, 3 vols. (New York, 1977), available on the Internet at the Website “Witchcraft in Salem Village“. Information on the family of Mercy Lewis comes primarily from Sybil Noyes, Charles Thornton Libby, and Walter Goodwin Davis, Genealogical Dictionary of Maine and New Hampshire (1928-33; reprint, Baltimore, Md., 1996). There is no detailed published account of the Indian wars on the Maine frontier, but much of the relevant evidence is included in James Phinney Baxter, ed., Documentary History of the State of Maine, in Collections of the Maine Historical Society, 2d ser., vols. 4 (1889), 5 (1897), 6 (1900), 9 (1907). Information about Falmouth in the seventeenth century is contained in William Willis, The History of Portland, from 1632 to 1864 (Portland, 1865).

This article originally appeared in issue 2.3 (April, 2002).

Mary Beth Norton is the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of American history at Cornell University. Interested in the relationship of gender and politics in early America, she has just completed a book on the Salem witchcraft crisis, In the Devil’s Snare (New York, forthcoming in October 2002), from which this article is drawn.