The Scenographia Americana (1768)

A transnational landscape for early America

Visually retentive readers of Fred Anderson’s award-winning Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (2000) will recall its centerpiece, the Scenographia Americana: or, A Collection of Views of North America and the West Indies . . . From Drawings Taken on the Spot, by Several Officers of the British Army and Navy, a twenty-eight print series of North American landscapes from Quebec to Guadeloupe, published in London in 1768. It is unquestionably the most impressive representation of Anglo-American landscapes in the eighteenth century, with no subsequent rivals until the publication of William Birch’s Views of Philadelphia in 1800 or, more appositely, Joshua Shaw and John Hills’s Picturesque Views of American Scenery (Philadelphia, 1819-21). Anderson and his publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, performed a much-needed service to scholarship in reproducing the series in full for the first time since the eighteenth century.

Assiduous readers of this journal will recall that its first issue featured a roundtable on Anderson’s book. None of its participants mentioned the Scenographia Americana. Indeed, no reviewer of Crucible of War mentioned these landscapes, with the telling exception of my fellow Canadian historian Ian K. Steele. Something about the Scenographia Americana causes visual amnesia. The William and Mary Quarterly has never indexed the Scenographia Americana, despite publishing its prints as illustrations. My quixotic task here is to try to gain for this remarkable work more of the recognition it deserves.

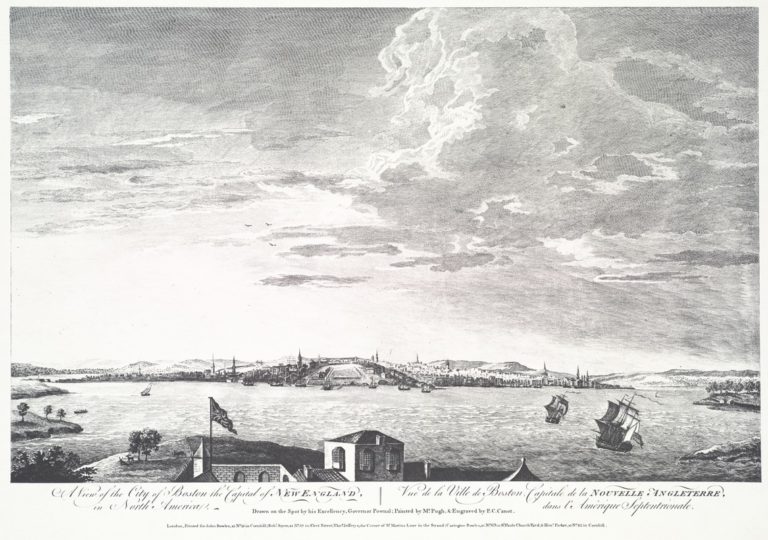

The Scenographia Americana begins with views from Canada: Quebec City, the Montmorency Falls, Cape Rouge, the Gaspé, Rock Percé, the Miramichi Valley, Montreal, and Louisbourg (fig. 1). Then follow four views of cities in long-settled British North America: New York (twice), Boston, and Charleston. Next are four views of dramatic riverine landscapes in New York and New Jersey: the Jersey Palisades, the Catskills as seen from the Hudson, the Great Cohoes Falls on the Mohawk River, and the Passaic River Falls (fig. 2). The next two prints show the Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and an imaginary scene of an American farm (fig. 3). The rest of the series shifts to the Caribbean, with four views of the harbor and city of Havana, two street scenes of Havana, one view of the British attack on Roseau, Dominique, and three scenes around Guadeloupe (one of a battle and two of the British occupation forces).

What view of the world could consistently include the fortifications of Havana, the Passaic Falls, and a village on the Miramichi River? The answer is: a global perspective on the vastly expanded British Empire that developed after the Seven Years’ War. Though some of its most striking scenes are of places in what would become the United States, the landscape of the Scenographia Americana does not fit an American national paradigm. (Perhaps for this reason, Crucible of War silently reordered the series, so that it began with the views of places that became parts of the United States: Boston, Charleston, and New York, and then landscapes in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—in defiance of the series’ table of contents.) The Scenographia Americana is implicitly an imperial travelogue through the British North American colonies, drawing eclectically on previously published visual narratives of events during the recently concluded war. While it has elements of a battlefields tour, its strongest emphasis was geographically scenic: how did places of British involvement during the Seven Years’ War look?

In defiance of the war’s narrative, the series takes the viewer down the Saint Lawrence from Quebec, passing by Louisbourg when chronology would dictate that it begin with the siege of that fortress in the year before the attack on Quebec. General James Wolfe’s aide-de-camp Captain Hervey Smith drew the Miramichi valley, the Gaspé coast, and the Rock Percé while the invasion fleet sailed from Halifax up the Saint Lawrence to Québec in 1759. The series privileges scenic itinerary over historical narrative.

As a commemoration of victory, the Scenographia Americana has an oddly tranquil, picturesque quality (fig. 4). Why have views of three long-British ports where no battles took place? Why the scenes of waterfalls? Why so much dramatic scenery along the invasion route to Québec? Why such emphasis on the exoticism of Havana’s peoples and vegetation? Why conclude with British military lounging at Fort Royal on Guadeloupe? For that matter, why remind British viewers at all that Guadeloupe and Havana had been given up in the Treaty of Paris after massive British losses to take them? The overall impression conveys satisfaction with the peaceful beauty of Britain’s North American realms, with an aversion to conflict and triumphalism (fig. 5).

Nearly all of the ScenographiaAmericana’s prints had already been published as parts of shorter series issued during or shortly after the Seven Years’ War. Captain Smyth had dedicated Six Views of the Most Remarkable Places in the Gulf and River of St. Laurence to prime minister William Pitt in 1760, when his war strategy still prevailed. Former Massachusetts governor Thomas Pownall had published Six Remarkable Views in the Provinces of New-York, New-Jersey, and Pennsylvania in North America/ Sketched on the Spot in 1761, shortly after his return from the colonies and just before he became commissary of British forces on the Continent. Lieutenant Archibald Campbell, royal engineer, had already published his views of Dominica and Guadeloupe in 1762 and 1764. In 1764, Elias Durnford, royal engineer, dedicated his Six Views of the City, Harbour, and Country of Havana to the Earl of Albemarle, commander in chief of the expedition to Cuba, to whom Durnford was aide-de-camp.

An apparent peculiarity of these earlier wartime series is their use of bi- and trilingual titles, including the languages of Britain’s defeated foes, France and Spain. This multilingualism signaled a profound shift in Britain’s cultural relations with the Continent: it had become a net exporter of graphic art. The publishers of the Scenographia Americana—John Bowles, Robert Sayers, Thomas Jeffreys, and Henry Parker—were among the foremost entrepreneurs of the British print industry, and Pownall’s artistic collaborator, Paul Sandby, was a successful promoter of topographic landscape art. In the same year that the Scenographia Americana was published, Sandby helped found the Royal Academy (an institution dedicated to the improvement and dissemination of visual art in Britain), and he became drawing master at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. In these roles he helped redirect British landscape art toward recording scenes “on the spot” and trained British officers to do so wherever they went in Britain’s newly global empire.

Students of early America may also neglect Scenographia Americana because its most powerful appreciations of distinctively American scenes were drawn by Thomas Pownall, erstwhile lieutenant governor of New Jersey, governor of Massachusetts, and appointee to the governorship of South Carolina—all provinces represented in the Scenographia Americana. Pownall secured these appointments as a favorite of Lord Halifax, president of the Board of Trade, and he actively supported William Pitt’s strategy of eliminating France’s colonies in North America. His governorships allowed him military ambitions on a continental scale, and he took a keen interest in the strategic implications of North American topography. In 1755 he sent survey parties up each of the major rivers of northern New England, with orders to pay particular attention to waterfalls and riverine defiles. In that same year, Lewis Evans published his Map of the Middle British Colonies in North America and dedicated it to Pownall. As the prints from his drawings show, Pownall’s military interest in topography was entirely harmonious with the practice of a landscape art that appreciated American scenery, especially its wondrous rivers.

Pownall was an arch exponent of a reorganized British empire that would have benignly integrated the American provinces’ social and economic development—including their representation in an imperial Parliament. In 1768, the year of the Scenographia Americana, Pownall, now a member of Parliament, reiterated and elaborated these views in the fourth edition of his Administration of the Colonies, first published in 1764.

The winter of 1767/68 was the highpoint of British governmental optimism about administration of its North American colonies. The year before, Parliament had rescinded the miscalculated Stamp Act. Under the leadership of Charles Townsend, Parliament then devised a hopefully inoffensive fiscal program for the North American colonies and a specialized bureaucracy to administer it. Revenue would accrue from duties on imports to the colonies and be spent solely on their imperial administration. A new American Board of Customs Commissioners, based in Boston, would collect the duties. Townsend died in September 1767, but the Duke of Grafton, who succeeded him as de facto head of government during William Pitt’s incapacitating illness, furthered Townsend’s strategy of Parliament’s systematizing colonial administration. New Vice-Admiralty courts in Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston would enforce and adjudicate the actions of the new customs service’s officers. A new Colonial Department, with Lord Hillsborough as its first secretary, would provide the colonies with a coherent administration for the first time. Lord Halifax had been urging such an administration since the late 1740s, and its program made sense to nearly everyone who thought about colonial government. Benjamin Franklin endorsed it. Vehement parliamentary denouncers of the Stamp Act, such as Colonel Isaac Barré and Edmund Burke, tacitly approved it.

The Scenographia Americana corresponded closely with this imperial optimism. Its sublime landscapes of the Middle Colonies linked them with those of the empire’s vast accessions in Canada; together they implied a reassuring familiarity with the territories to be governed (fig. 6). The scenes from Havana and Guadeloupe reminded viewers that prosperous peace had succeeded fiscally ruinous war. Though Cuba and Guadeloupe had been returned in the peace settlement, the Free Port Act of 1766 authorized trade with Spanish and French colonies from Jamaica and Dominica respectively. The rising sun in the last print provides a subtly optimistic symbol of these liberalized trades by visually echoing the sun’s rays in the stripes of the enormous Union Jacks flying off the transoms of three British ships returning home (fig. 7).

The optimism manifested by the Scenographia Americana was as ephemeral as the rising sun’s rays. The cold light of day shown when word reached London in April that the Massachusetts General Court had endorsed Samuel Adam’s circular letter condemning the Townshend Acts as taxation without representation. Lord Hillsborough, as secretary of the Colonial Department, instructed Governor Francis Bernard to require the General Court to rescind the circular letter, and he instructed the other governors to dissolve their colonies’ assemblies before they had a chance to approve the circular letter. Both directives backfired. In June, threatening protests against the customs commissioners’ seizure of John Hancock’s Liberty propelled them to take refuge at Castle William and to request military protection, which arrived in October. After the Boston Massacre seventeen months later, Paul Revere commemorated these developments by publishing A View of Part of the Town of Boston in New England and British Ships of War Landing Their Troops! 1768, with a sarcastic dedication to Lord Hillsborough’s “well plan’d expedition, formed for supporting ye dignity of Britain & chastising ye insolence of America” (fig. 8).

Revere showed no topographic interest in designing this print: he was creating iconic propaganda for anti-imperial militancy. British officials and military officers ceased constructing a landscape of the now-insurgent American colonies, though they continued to do so in other North American colonies. Yet to the bafflement of American cultural nationalists—such as Thomas Jefferson, the publisher Mathew Carey, and the painter Charles Willson Peale—indigenous efforts languished fitfully for decades.

In the development of a British global landscape, however, the Scenographia Americana was just an early example of a broadening effort. Over the next several decades many dozens of agents of empire—royal officials, army and naval officers, professional artists, and their respective spouses—made drawings of overseas scenes for reproduction back in Britain. From Quebec, military officers, cartographic surveyors, and officials’ wives sent home watercolors and sketches for reproduction as engravings to show the newly conquered province’s sublime rivers and picturesque countryside. Artists aboard Captain James Cook’s voyages also created transfixing images of the Pacific’s exotic scenery and peoples to feed a growing domestic appetite for images of global Britain. In the 1770s, for the first time British topographic artists extensively recorded Caribbean scenery and peoples. At roughly the same time in India, professional landscape artists were beginning to undertake systematic painting expeditions, and, in New South Wales (which would become Australia), naval and military officers and convicts began creating a visual record of antipodean peoples, scenery, and natural history.

Had the thirteen colonies remained a part of the British Empire their inhabitants would unquestionably have identified with this global British landscape. And they would have had a stronger, and earlier, visual appreciation of their landscape than would prove to be the case. Take Niagara Falls for an example. In 1760-61, while exploring Britain’s newly acquired territory, a young British officer, Thomas Davies, made the first recorded on-the-spot drawings of the falls. Two of these drawings were published in 1768; they established the classic view of the Horseshoe Fall from the Canadian side. A sketch that same year by another officer, William Pierie, inspired Richard Wilson, Britain’s premiere landscape artist, to paint The Falls of Niagara, which he exhibited in 1774 at the Royal Academy. A series of British officers in the 1780s and 1790s continued to sketch the falls, each seeking a new vantage point from which to represent them. In 1799, Ralph Earl, a proscribed Loyalist, would render the falls from his own observations, the first American to do so.

American landscape art of the early nineteenth century was largely a by-product of this late eighteenth-century British global landscape. This is something historians of American art have generally overlooked, tending as they have to focus on burgeoning American nationalism. But in doing so they are liable to the anachronism of neglecting the inherent cultural contingency of revolutions: revolutions depend on overthrowing a political regime, but the previously sustaining culture still has ineffable force. Appreciating the visual development of an American landscape depends on a transnational perspective on Anglo-American landscape art, an appreciation that attention to the Scenographia Americana may encourage.

Conversely, the Scenographia Americanais a stark reminder of the challenges facing British authorities in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War: they now possessed an empire that would require the accommodation of French Roman Catholics, the appropriation of an existing empire in India, the expansion of a slave regime throughout the Atlantic, and the quelling of rebellion within the most thoroughly British of Britain’s overseas realms, the original mainland colonies of North America. By creating harmonious images of Britain’s colonial periphery, the Scenographia Americana deflected attention from the growing burdens of empire.

Further Reading:

The Scenographia Americana can be viewed at a number of libraries, including the American Antiquarian Society, the Boston Public Library, the Library of Congress, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the New York State Library, and the William L. Clements Library.

For an exceptional discussion of the Scenographia Americana, see Bruce Robertson, “Venit, Vidit, Depinxit: The Military Artist in America,” in Edward J. Nygren, Bruce Robertson, Amy R. W. Meyers, Therese O’Malley, Ellwood C. Parry III, and John R. Stilgoe, Views and Visions: American Landscape before 1830 (Washington, DC, 1986), 84-87; this collection is the best book on early American landscape art, but see also Karol Ann Lawson, “A New World of Gladness and Exertion: Images of the North American Landscape in Maps, Portraits, and Serial Prints before 1820” (Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia, 1988) and Lawson, “An Inexhaustible Abundance: The National Landscape Depicted in American Magazines, 1780-1820,” Journal of the Early Republic, 12 (Fall 1992): 303-30. The most comprehensive survey of topographic art of the United States and its colonial predecessors is Gloria Gilda Deák, Picturing America: Prints, Maps, and Drawings Bearing on the New World Discoveries and on the Development of the Territory That Is Now the United States (Princeton, 1988). The fullest description of the Scenographia Americana is still I. N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909, 2 vol. (New York, 1916), 1: 281-95.

On the development of a global British landscape, see John E. Crowley, “A Visual Empire: Seeing the British Atlantic World from a Global British Perspective,” in The Creation of a British Atlantic World, Elizabeth Mancke and Carole Shammas, ed. (Baltimore, 2005), 383-403; Crowley, “‘Taken on the Spot’: The Visual Appropriation of New France for the Global British Landscape,” Canadian Historical Review, 86 (March 2005): 1-28; Crowley, “Picturing the Caribbean in the Global British Landscape,” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, 32 (2003): 323-46; Barbara Maria Stafford, Voyage into Substance: Art, Science, Nature, and the Illustrated Travel Account, 1760-1840 (Cambridge, Mass., 1984); Bernard Smith, “Art in the Service of Science and Travel,” in Imagining the Pacific: In the Wake of the Cook Voyages (New Haven, 1992), 1-40; Michael Jacobs, The Painted Voyage: Art, Travel and Exploration 1564-1875 (London, 1995); Timothy Clayton, The English Print 1688-1802 (New Haven, 1997).

On the Scenographia Americana’s political context, see Lawrence Henry Gipson, The Triumphant Empire: The Rumbling of the Coming Storm, 1766-1770 (New York, 1965); C. A. Bayly, “The First Age of Global Imperialism, c. 1760-1830,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 26 (1998): 28-47; P. J. Marshall, “Britain Without America—A Second Empire?” The Oxford History of the British Empire, vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century, (New York, 1998), 576-95; Eliga H. Gould, The Persistence of Empire: British Political Culture in the Age of the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, 2000). On the inherent instabilities of imperial hegemony, see Anthony Pagden, Peoples and Empires: A Short History of European Migration, Exploration, and Conquest (New York, 2001).

On the reorientation of early Anglo-American history from its proto-United States teleology toward transnational perspectives on the Atlantic World and beyond, see David Thelen, “The Nation and Beyond: Transnational Perspectives on United States History,” Ian Tyrrell, “Making Nations / Making States: American Historians in the Context of Empire,” Nicholas Canny, “Writing Atlantic History; or, Reconfiguring the History of Colonial British America,” Journal of American History: The Nation and Beyond: A Special Issue, 86 (December 1999): 965-1155, 1015-44, 1093-1114; “AHR Forum: The New British History in Atlantic Perspective,” American Historical Review, 104 (April 1999): 426-500; Heinz Ickstadt, “American Studies in an Age of Globalization,” American Quarterly, 54 (December 2002): 543-62. Common-place demonstrated the potential of such approaches in its special issue on “Pacific Routes” (January 2005). The best history of British America from a transnational perspective is Stephen J. Hornsby, British Atlantic, American Frontier: Spaces of Power in Early Modern British America (Hanover and London, 2005). Hornsby’s analysis uses a rich array of graphic evidence, including the Scenographia Americana.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.2 (January, 2006).

John E. Crowley is professor emeritus at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is writing a book, tentatively titled Counterfeit of Empire, about the development of a global landscape in British visual culture in the period from the Highland Rebellion of 1745 to the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. In rough chronological and geographic order, it studies the relationships between artistic and political interests in representations of landscapes in Scotland, England, Canada, the Pacific, the Caribbean, the United States, India, and Australia.