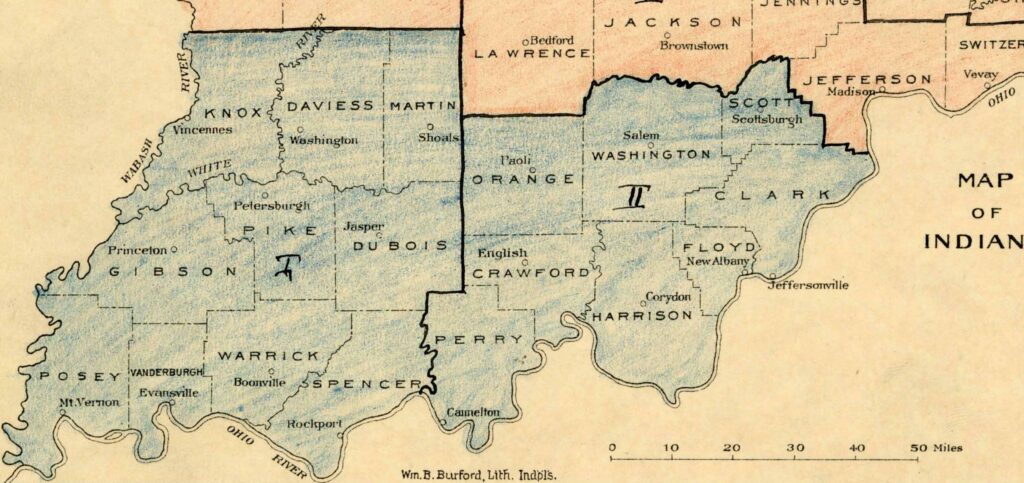

During the campaign of 1840, George H. Proffit and Robert Dale Owen faced off against each other to represent the First District in the U.S. House of Representatives. They traveled together across the Pocket’s backroads, as was the custom, for two long, hot months in the summer of 1839, riding together on horseback to speak before crowds at towns, county seats, and at impromptu roadside encounters. They would speak for hours at a time, notwithstanding interruptions from the crowd, followed by lengthy rebuttals.

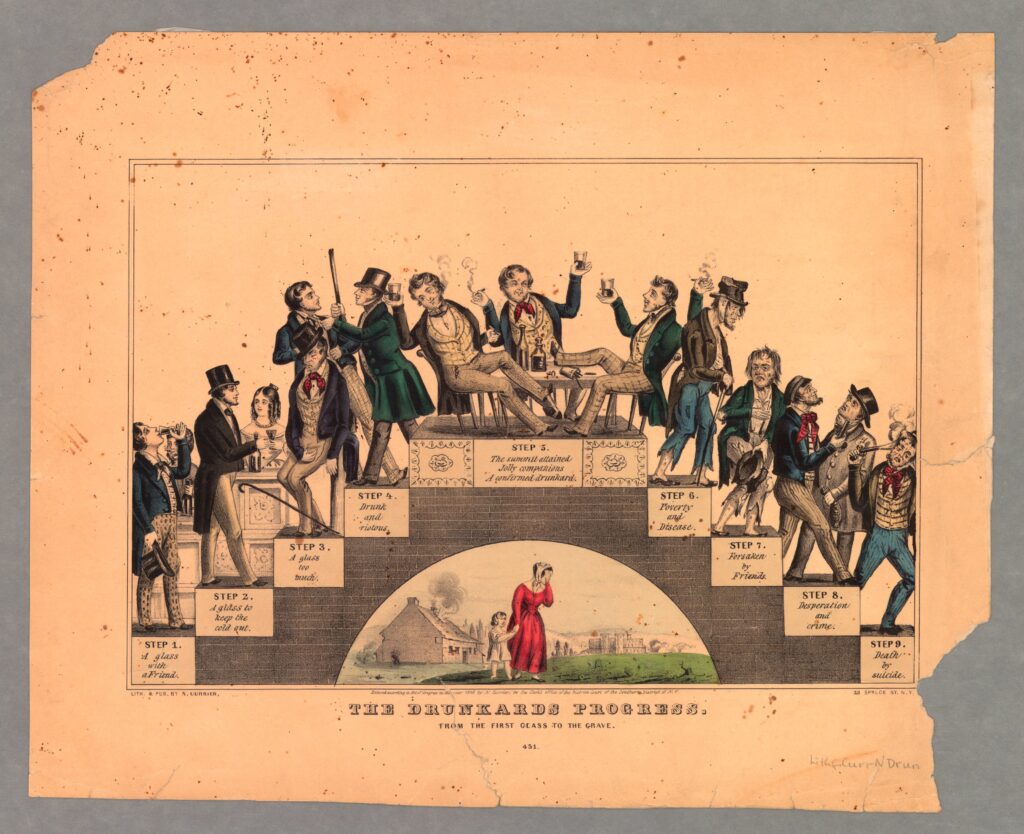

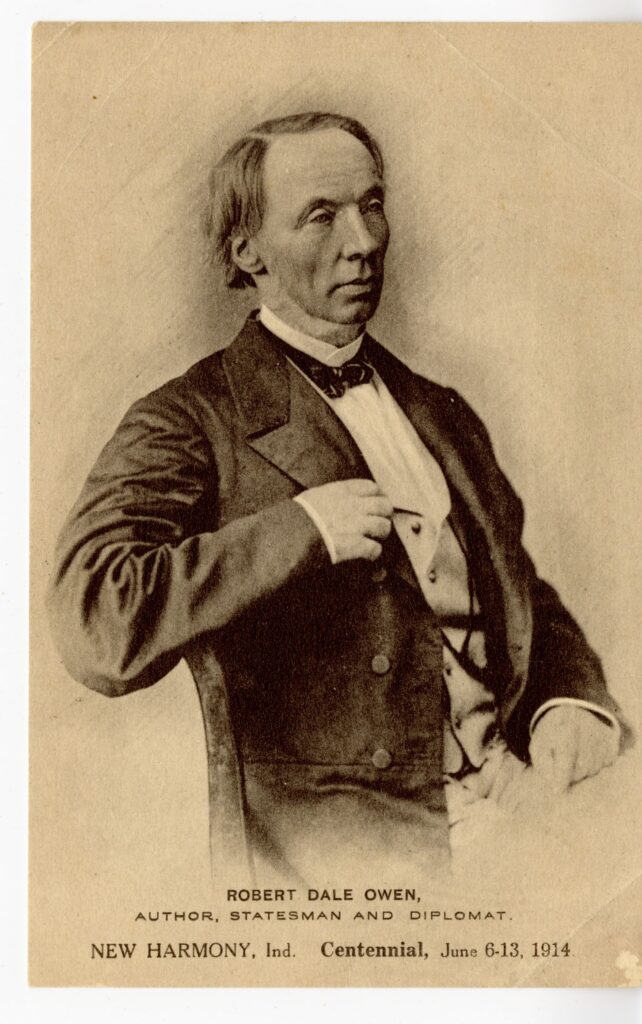

Proffit’s manner of speaking was honed at the country store. There, intimacy and mutual trust were the coin of the realm. Owen was at a disadvantage on the stump. He relied on a plodding style of argumentation—lecturing, really—developed during his years as a gadfly denouncing the ills of society to thin crowds at the Hall of Science in New York City, an assembly for radicals.

Owen was earnest on the campaign trail, not entertaining. He had the awkward habit “of keeping his hands in his breeches pockets,” a Whig paper observed. “As he warms and rises in the importance of his subject, deeper does he plunge his hands into his breeches.” By most accounts, Owen did himself few favors when delivering a stump speech. He lost to Proffit by a 13 percent margin, a rout that cannot be fully attributed to late entrance into the race.

Rather than fold after this harrowing defeat, Robert Dale Owen returned to the campaign trail time and again. He became a regular party speaker, aided in part by sheer availability. That is, he could afford to spend months away from business affairs focused on the election canvass, doing committee work, and attending conventions.

Owen traveled the electioneering circuit for Martin Van Buren in 1840, James Polk in 1844 and Lewis Cass in 1848, not to mention for his own U.S. House campaigns. Owen eventually learned to give a passable speech through workman-like practice and sheer force of will. He proved indefatigable, an advantage in party service during this era that was second only to skills at speechifying.

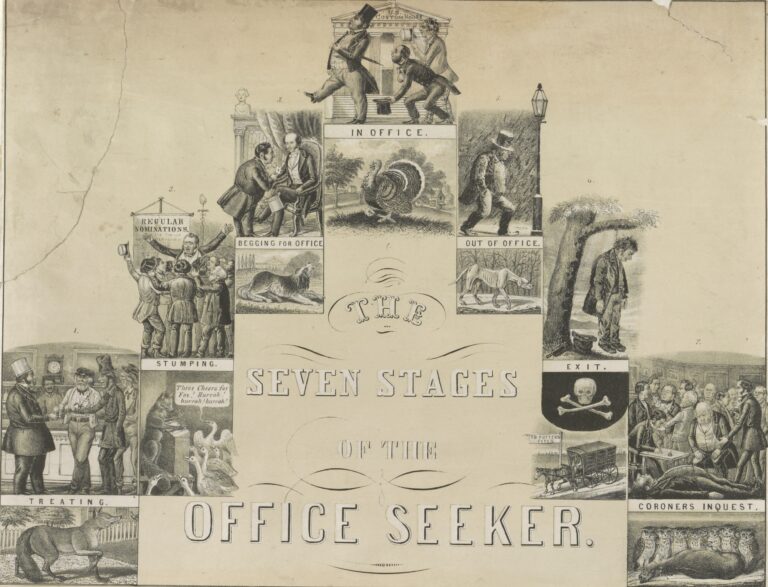

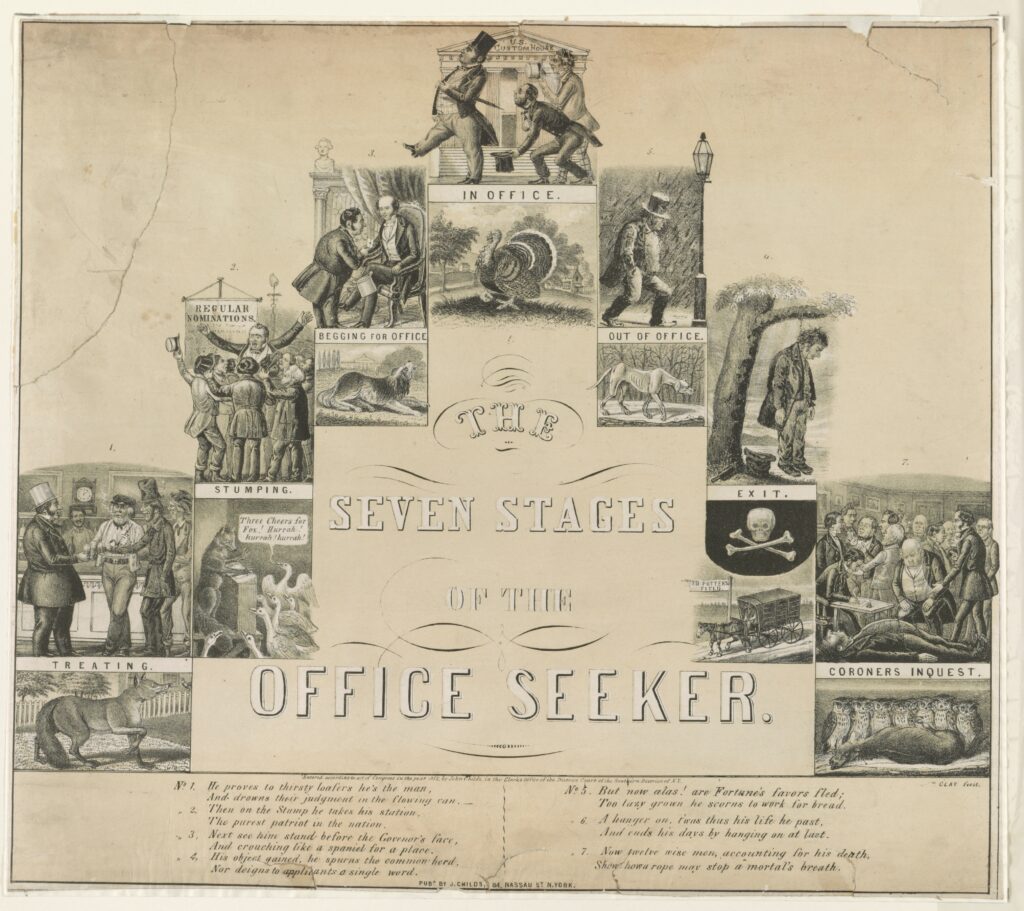

In and Out of Office

When George H. Proffit embarked in the Summer of 1843 for Rio de Janeiro on the USS Levant, a sloop-of-war that shuttled diplomats to their posts in Latin America, his appointment was the culmination of a long career in public life. Proffit was a popular congressman, and, before that, a state legislator. Now he was leaving the backwoods of southern Indiana, with its coarse manners and meagre living, to serve as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the court of Brazilian Emperor Pedro II. A group of New York merchants even organized a dinner celebrating the Hoosier’s departure for “standing manfully in defence [sic] of the President.”

The journey was not easy. It took two and a half months amid squelching heat to make the voyage from Hampton Roads on the Virginia coast to Rio, crossing the Caribbean and making port several times on the way. And then, after all these labors, Proffit’s tour of duty was over almost as soon as it began. He arrived in Brazil with an unfortunate status as a diplomat without the confidence of his own government.

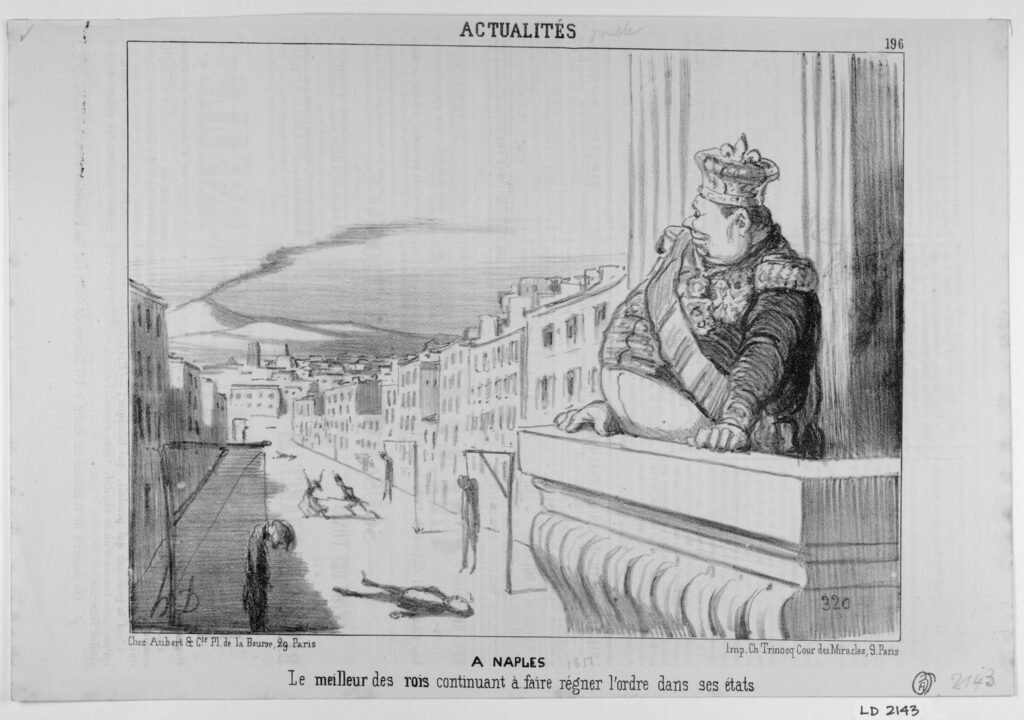

Mere weeks after disembarking, the U.S. Senate rejected George Proffitt’s confirmation as minister by a vote of thirty-three to eight. More than a disappointment, it was a humiliation. In 1842, John Tyler—an accidental president after the death of William Henry Harrison—had broken decisively with the Whigs after vetoing party-line measures on banking and the tariff. After waiting more than a decade in the opposition, Whigs lost a chance—their only, it would turn out—to govern as a majority on the party’s own terms. Congressman Proffit followed Tyler into political apostasy and received his just reward, a recess appointment for the Brazilian mission at $9,000 per year (or about $300,000 today).

The personal triumph was brief. Henry Clay, the Whig leader preparing to run for president, bitterly denounced Proffit on the Senate floor, along with other members of Tyler’s “corporal’s guard” of ex-Whigs seeking patronage. Following humiliation came disaster. On February 28, the twelve-inch guns of the USS Princeton exploded during official inspection. The accident brought a sudden and gruesome end to Tyler’s Secretary of State, Abel P. Upshur, who envisioned uniting pro-slavery forces in the Western hemisphere by forming a grand alliance with Brazil. The State Department was rudderless at the very moment that Proffit had been stripped of authority by the U.S. Senate. Essentially, he was stranded in South America.

A mere eight months after leaving home, then, acting-Minister Proffit slunk quietly back into the country on the USS Cyane. Earlier, during the heady moment of Whig triumph in the Election of 1840, he had been celebrated as a party hero. His frenzied efforts stumping on behalf of the Harrison-Tyler ticket were decisive in carrying Indiana’s Democratic-leaning Pike County by a razor-thin margin of 156 votes. “We have a whole team in the person of little George H. Proffit,” boasted a local party paper, marveling at the energy of a man who was but 5 feet and 4 ½ inches tall.

Upon returning from Brazil, Proffit was abandoned by longtime friends who believed that he dropped the Whig standard for little more than a patronage grab. He was hounded by local papers as “the little traitor.” Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, a longstanding antagonist, crowed that Proffit’s diplomatic tenure was so irrelevant that he was never formally received at court. In truth, the alleged slight was likely due to poor timing: the newly coronated Emperor’s feud with his brother-in-law, the Count of Aquila, had brought court affairs to a standstill. The palace of São Cristóvão also happened to be under renovation. Still, the charge appeared to confirm Proffit’s sudden irrelevance.