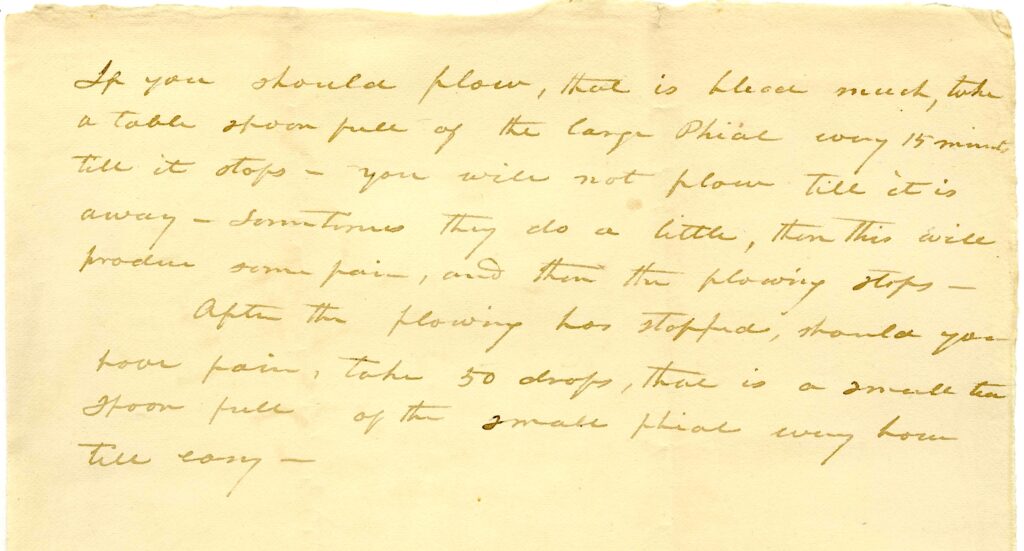

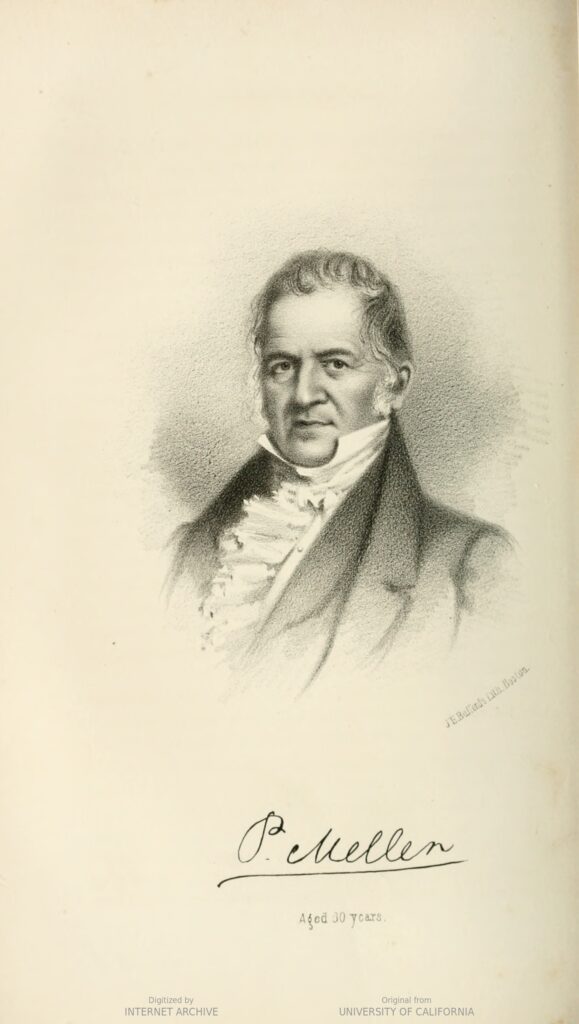

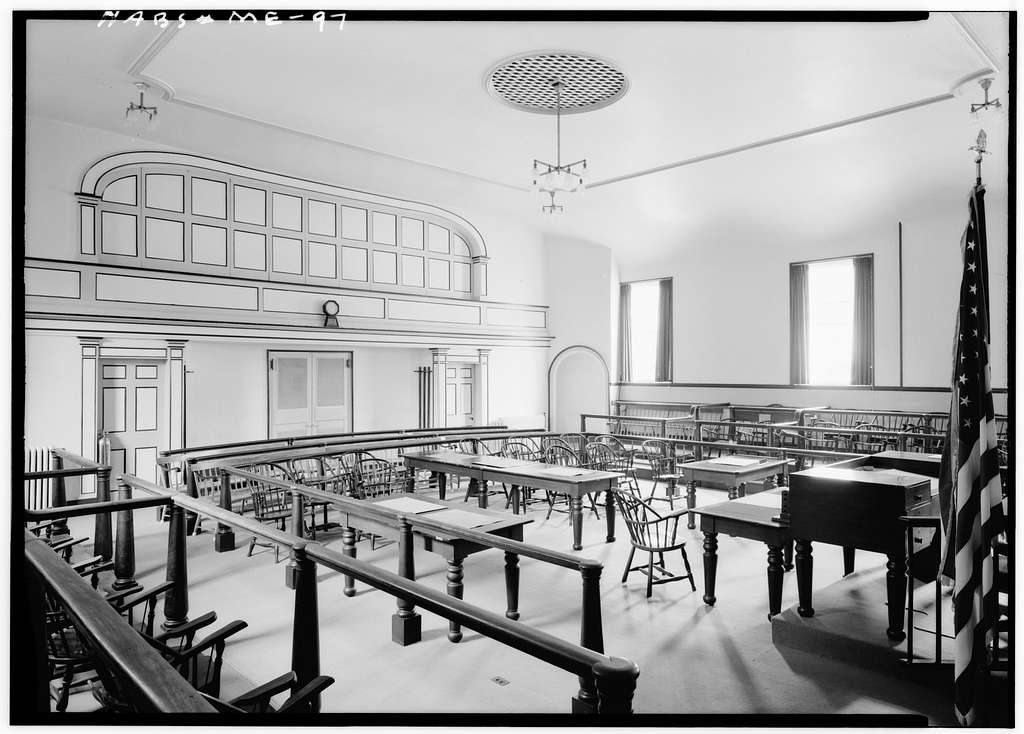

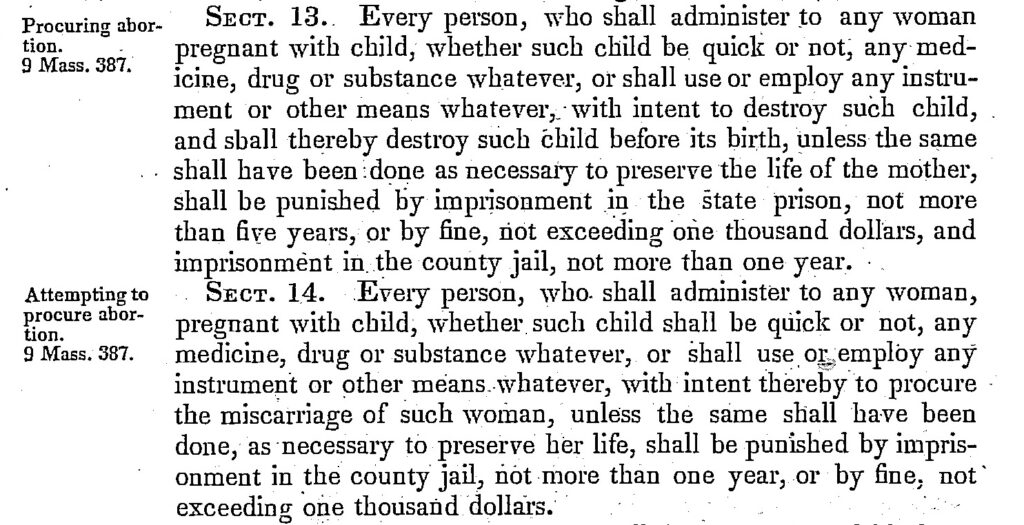

Only when the mother died did the charge escalate to second degree murder (in an abortion) or to manslaughter (in miscarriage). This escalation was a long-standing feature of Anglo-American law, when unintentional deaths occurred in the commission of a crime. Maine newspapers provide evidence of just two Maine abortion trials in the twenty years after the 1840 law, and both involved dead mothers and charges of second-degree murder. The first, in 1843, ended in acquittal. The second in 1851 led to the conviction of a mill-town doctor with a reputation for helping mill girls out. Dr. James Smith of Saco drew a life sentence at hard labor in the state prison; high public interest centered on an unusually horrifying disposal of the young woman’s body. But Smith appealed, hiring a top Portland lawyer (recently U.S. attorney general in the Polk administration, and soon to-be justice on the U.S. Supreme Court). The entire conviction was reversed on a technicality (a “writ of error”). The high court’s decision tied itself in knots parsing the words of the abortion section of the 1840 law, with paragraphs of confusing medical claims about miscarriage, fetal viability, premature births, and abortion, most of it not relevant to the writ of error. In the end, the reversal rested on the original indictment’s failure to include intent (“to destroy such child”). Dr. Smith was a free man, facing a hue and cry in the New England press.

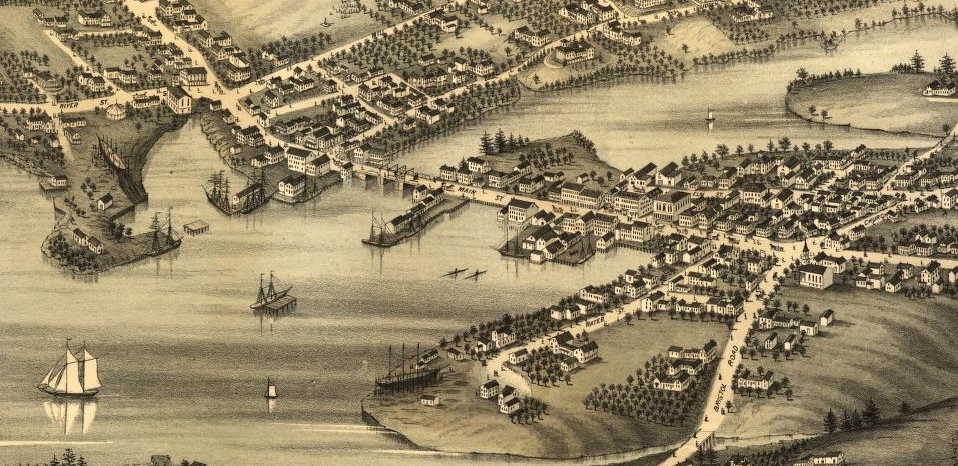

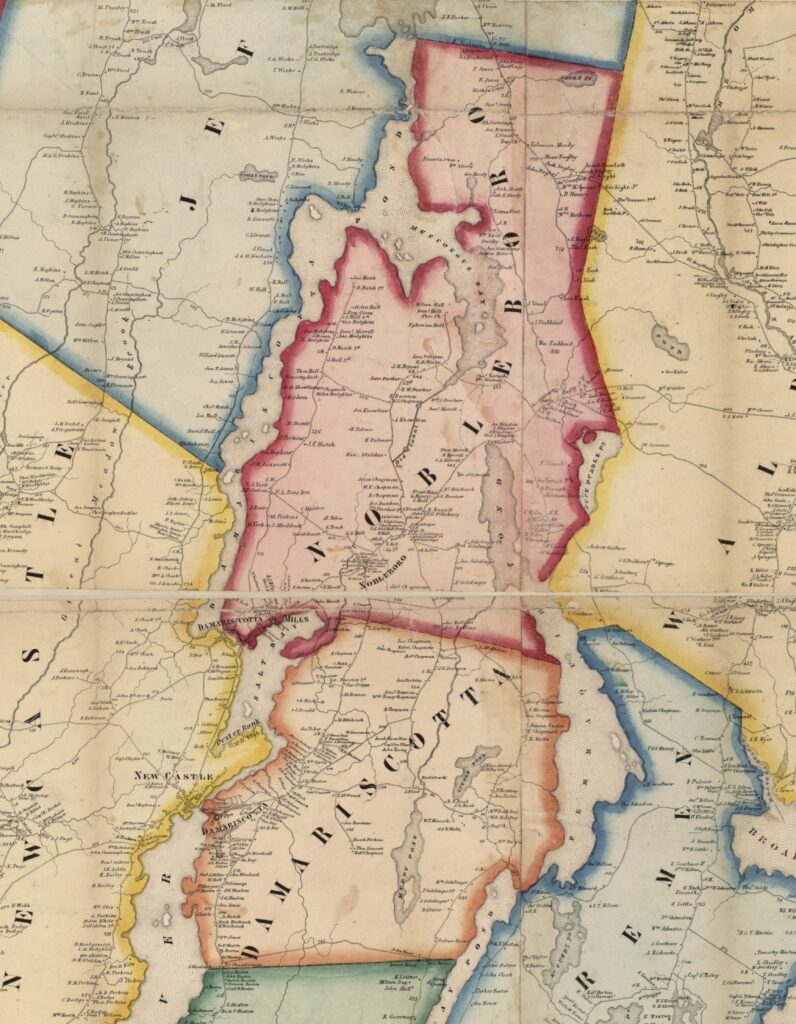

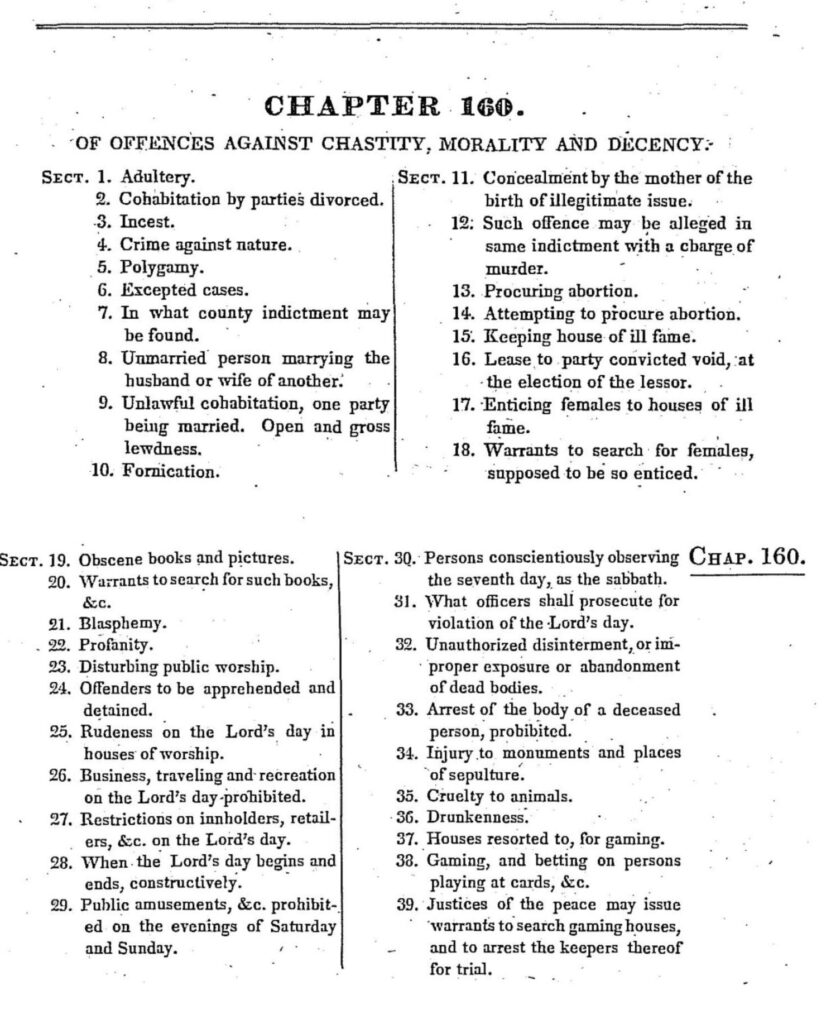

Just two newsworthy cases in twenty years suggests a thin record of enforcement. Perhaps there was a trickle of misdemeanor cases in the county courts, yet to be uncovered? Yet absent the death of the mother, abortions rarely came to light, when all parties concerned strive to keep it private. An unusual mid-century physician in Hallowell published statistics of 1,000 births in his two-decade career and noted with mild disapproval that “cases of abortion occur too frequently in this community. . . most of them among married women.” Physicians were the most likely to know about these things, either in hearing scuttlebutt from patients (like Doctors Clark and Ford in Lincoln County), from dealing with complications caused by inexpert abortions, or from doing the procedure themselves. It is no surprise, then, that the biggest push to criminalize abortion in the U.S. came at the behest of the American Medical Association, which lobbied every state government in 1860 to pass or tighten laws on abortion.

Meanwhile, Dr. Moses Call continued to practice in Lincoln County into the 1870s, making a splash in national news circuits when his considerably younger second wife filed for divorce. Among her complaints, in the nine-day trial, was her discovery that he was a convicted abortionist; after 40 years, the Call/Chapman case finally broke into newsprint! The estranged wife was awarded custody of a young son and an extraordinary alimony of $14,450, a further indication of a Dr. Call’s unusually profitable profession. Henry Chapman married, had five children, and lived out an obscure life into his fifties as a ship joiner. Deborah also married, but not until age 31, a long delay suggesting reputational fallout from the locally infamous trial. Her marriage lasted nineteen years, until her death. Most unusually, she never bore a child.

Further Reading

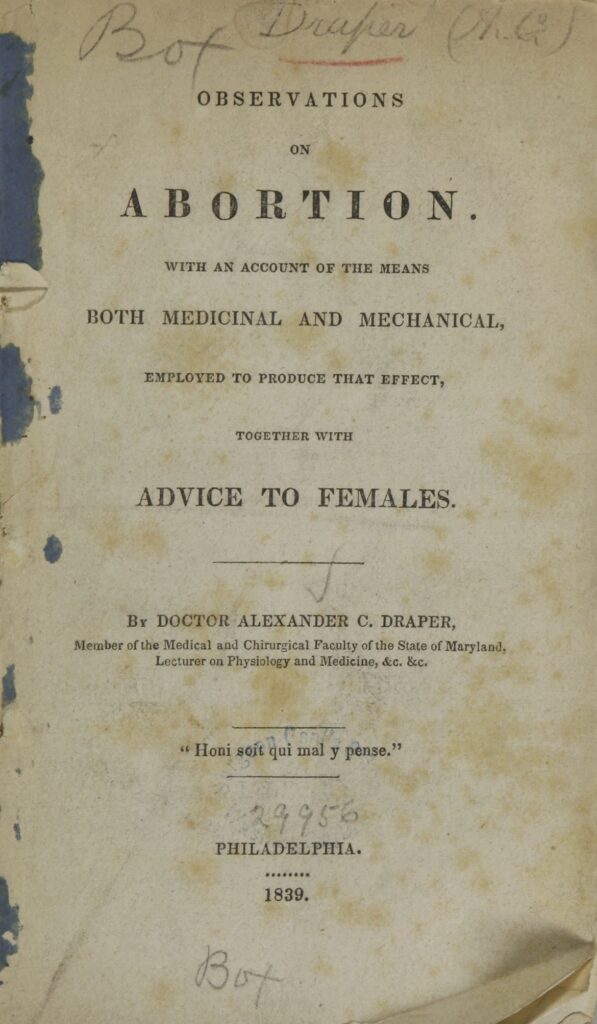

James C. Mohr’s classic, Abortion in America (Oxford University Press, 1978), provides an indispensable overview of the nineteenth-century criminalization of abortion.

Cornelia Hughes Dayton gave us the first microhistory of a 1740s abortion case in Connecticut: “Taking the Trade: Abortion and Gender Relations in an Eighteenth-Century New England Village,” William and Mary Quarterly 48 (Jan. 1991): 19-49. There is a rich companion website with original documents.

Brook Lansing Mai has a recent excellent addition to the microhistory genre involving a French immigrant in New York City in 1844: “‘The helpless French girl’: Seduction Narratives in a Nineteenth-Century Abortion Trial,” Gender & History 36 (July 2024): 313-26.

Aaron Tang, a law professor, offers the most comprehensive account of state statutes up to 1868: “After Dobbs: History, Tradition, and the Uncertain Future of a Nationwide Abortion Ban,” Stanford Law Review 75 (2023).

Maine Digital Repository holds the pardon file: Moses Call Files.

Ancestry.com and Genealogybank.com provided essential sources for scoping out the cast of characters.

This article originally appeared in October 2024.

Patricia Cline Cohen is the Edward A. Dickson Emerita Professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of The Murder of Helen Jewett: The Life and Death of a Prostitute in Nineteenth-Century New York (Knopf, 1998) and co-author of The Flash Press: Sporting Male Weeklies in 1840s New York (University of Chicago Press, 2008). In 2020, she embarked on a study of U.S. abortion practice and law from 1800 to 1860, and she continues to make progress on her joint biography of Mary Gove Nichols and Thomas L. Nichols, who in the 1850s notoriously advocated for women’s bodily autonomy.