The Wright Stuff

Stephen Douglas, Frederick Douglass, and the blackened reputation of Abraham Lincoln

The propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be denounced…lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

—Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852)

[The government] wants us to sing “God Bless America.” No, no, no, God damn America, that’s in the Bible for killing innocent people. God damn America for treating our citizens as less than human. God damn America for as long as she acts like she is God and she is supreme.

—The Reverend Jeremiah Wright, “Confusing God and Government” (2003)

It has become a commonplace of modern politics to bemoan the presumably sorry state of our election campaigns by comparing them with the 1858 U.S. Senate debates between Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln. The seven encounters around the state of Illinois exactly 150 years ago are often collectively regarded as the apogee of high-minded democratic discourse. “Lincoln-Douglas It Wasn’t,” reads the title of a blog entry on a George Bush-John Kerry debate in 2004. A suburban New York newspaper Website summed up its coverage of a 2006 debate for state senate with the headline, “It Wasn’t Exactly Lincoln-Douglas.” U.S. News and World Report described former presidential candidate John Edwards’s response to a 2007 video portraying him fussing with his hair by saying “it wasn’t the Lincoln-Douglas debates, exactly.” At one point in the presidential primary campaigns this spring, Hillary Clinton repeatedly called for Lincoln-Douglas styled debates with Barack Obama. “I think they would love seeing that kind of debate and discussion,” she said. The Obama campaign made a similar pitch to John McCain in response to the McCain campaign’s call for town meetings.

Of course, as anyone who has actually read the transcripts of the Lincoln-Douglas debates knows, they were characterized by often numbing repetition, mudslinging, and innuendo. The racial dimension of the innuendo was especially important. If patriotism is the last refuge of scoundrels, then racism—cloaked in the garb of anti-extremism—may well be the first.

Whether in fact Douglas was a scoundrel had become the key issue in American politics in 1858, and he was desperate to change the subject. That he was the likely Democratic nominee for president in 1860 was considered conventional wisdom by friend and foe alike. But Douglas was also widely considered damaged goods for the way he attempted to finesse the great political issue of his time, the expansion of slavery. In a time of increasing polarization, he consistently sought to seize the middle ground, a strategy that enhanced his political clout but that also generated suspicion that he would say or do anything for political gain. By the late 1850s, the key to his future lay in his reelection to a third term in the U.S. Senate. But, as Douglas well knew, that would happen only if he could shift the focus of the campaign away from his compromising legislative record to the record of an opponent who was not very well known outside Illinois but whom Douglas had the good sense to recognize as a mortal threat.

Douglas considered himself a patriotic nationalist, particularly compared with opponents he plausibly regarded as ideological and sectional. He had spent the previous decade navigating the treacherous slavery divide that had moved from a side issue before the Mexican War to the nation’s central problem. In 1850 Douglas crossed party lines to team up with Whig senator Daniel Webster, picking up the banner of the faltering Whig Henry Clay and getting the Compromise of 1850 through Congress and the White House. Many politicians and voters considered this legislative package the last word on the subject of slavery’s expansion. To be sure, proslavery advocates like John Calhoun and abolitionists like Harriet Beecher Stowe (who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin to protest the Fugitive Slave Act component of the compromise) would continue to carp about the national scourge. But they would do so primarily from the sidelines—at least until Douglas again leapt onto the national legislative scene.

Ironically, the man who undid the Compromise of 1850 was Douglas himself. Fishing for Southern support as he contemplated his presidential prospects, Douglas concocted a new bill, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he rammed through Congress in 1854. The new law broadened a concept of popular sovereignty (first championed by Democratic presidential candidate Lewis Cass in the 1840s) to allow the voters in a particular territory—rather than the national government—to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery. Douglas would claim for years to come that he didn’t care whether slavery was voted up or down and that his real commitment was to the democratic process. When the law led to a bloody guerilla war in Kansas territory and then a proslavery constitution there, questions arose about Douglas’s sincerity. If his real concern was democracy, could he rightly support a constitution that most knew to be the result of proslavery’s violent and intimidating tactics? The dilemma was made all the more difficult for Douglas by the fact that the Democratic Buchanan administration endorsed the largely fraudulent constitution. To claim, as he eventually would, that the process in Kansas made a mockery of popular sovereignty, Douglas would have to break with the president. Furthermore, this position would permanently damage Douglas’s standing among the very proslavery advocates the Kansas-Nebraska Act was supposed to attract. Douglas’s stratagem proved too clever by half and backfired. He returned to Illinois to campaign in 1858 with many Democrats fiercely opposed to him.

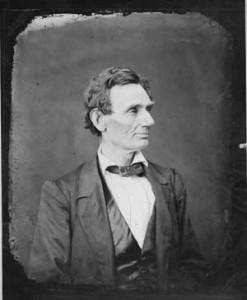

Douglas’s opponent for the Senate seat had his own intra-party divisions to navigate. Abraham Lincoln, nominee of the recently formed Republican Party, had lukewarm partisan support; in fact, some Republicans advocated exploiting Democratic divisions by making Douglas the Republican nominee. Moreover, the core of Republican support came from drifting fragments of the old Whig Party, many of whose members were deeply wary of abolitionist elements within the new Republican coalition. Lincoln would have to woo these skittish Whigs to prevent their defection to the Douglasite Democrats.

With its rickety coalition and little-known candidate, the deck appeared heavily stacked against the Republicans. Douglas was already a politician of national note and his party, though facing one of the greatest crises of its history, was venerable and established. So, when challenged to a series of seven debates around Illinois in the summer and fall of 1858, Douglas might well have declined, confident that his name and the party’s machinery would carry him to victory. But, of course, he did not. Why? The answer is that the pugilistic Douglas saw in the debates an opportunity to fatally fracture the fragile Republican coalition.

There were two core components of this strategy: The first, which Douglas unveiled in his opening remarks at the first debate in Ottawa, Illinois, and returned to repeatedly (in fact, the debates were more like a series of alternating speeches, not entirely unlike contemporary presidential “debates”), was an appeal to those he wanted to consider former rivals. Only a few years ago, he said, there were two great political parties, Democrats and Whigs. As a Democrat, Douglas battled worthy foes like the late Henry Clay. But whatever their differences, both parties were national in scope and patriotic in tone. Now, however, the nation faced the prospect of a splintered political system typified by the upstart Republicans, whose politics were overtly sectional and extremist. Lincoln’s famous 1858 “House Divided” speech, in which he asserted the nation could not indefinitely survive half slave and half free, was exhibit A in this line of argument. Douglas repeatedly used Lincoln’s words from this speech against him, citing it as evidence that he considered a civil war inevitable and even desirable. By contrast, Douglas presented himself as a voice of moderation, loyal to the sacred trust bequeathed to his generation by the Founding Fathers, insisting there was no good reason why the national experiment could not continue indefinitely.

This component was the high road. The low road was explicit racism. This is a white man’s country, Douglas said again and again. The problem with Abraham Lincoln is that he wants to make it a black man’s country, too. In debate after debate, Douglas repeatedly lumped Lincoln with an array of abolitionist leaders like Salmon Chase and Owen Lovejoy, whose brother Elijah had been murdered in Illinois in 1837 for publishing an abolitionist newspaper (as a state legislator, Lincoln sponsored and was one of the few signers of a resolution condemning the crime). Indeed, Douglas characteristically preceded any invocation of Lincoln’s political affiliation with the adjective “black”—he was the candidate of the “Black Republican” party.

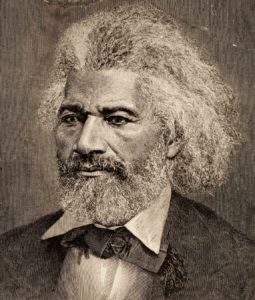

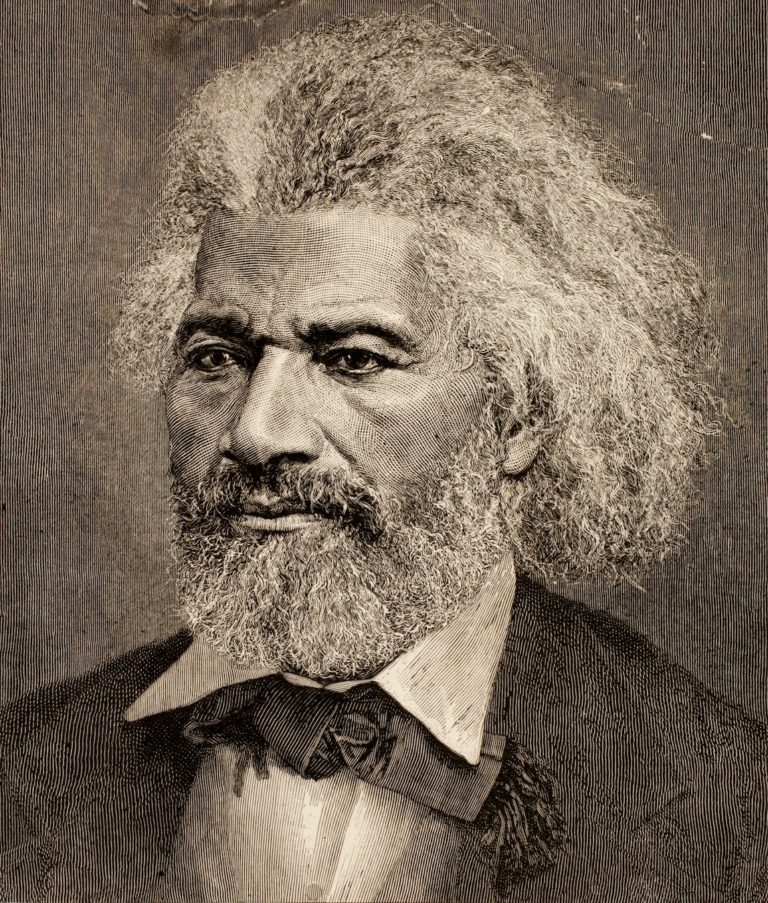

The quintessential Black Republican—the blackest of the black, as it were—was Frederick Douglass. By 1858, Douglass had established himself as the premier voice in American abolitionism. The former slave was now the publisher of an antislavery newspaper, and his oratory incited supporters and opponents alike. Nowhere was Douglass’s stirring oratory more potent than in his famous 1852 Independence Day speech, “What to the American Slave is the Fourth of July?” delivered before hundreds of listeners in Rochester, New York, and then widely republished. Douglass answered his question by saying “it is a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham…a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.” For Douglass, a civil war would be a matter of chickens coming home to roost.

Douglas invoked Douglass’s name a dozen times in the debates, most vividly in the second, at Freeport, when he offered his audience this (uncorroborated) masterpiece of race-baiting, accompanied by cries of “Black Republican” and “white, white”:

I have reason to recollect that some people in this country think that Fred. Douglass is a very good man. The last time I came here to make a speech, while talking from the stand to you, people of Freeport, as I am doing today, I saw a carriage and a magnificent one it was, drive up and take a position on the outside of the crowd; a beautiful young lady was sitting on the box seat, reclined outside, whilst Fred. Douglass and her mother reclined inside, and the owner of the carriage acted as driver. I saw this in your own town. All I have to say of it is this, that if you, Black Republicans, think the negro ought to be on a social equality with your wives and daughters, whilst you drive the team, you have a perfect right to do so.

Such rhetoric was appalling to some Americans in 1858, Lincoln among them. But for many, many others, it struck a chord—a chord too potent to be ignored by any politician. This is why Lincoln began the fourth debate, in Charleston, Illinois, with an avowedly racist line of argument that haunts his champions to this day. “I am not, nor have ever been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,” he said to applause. Lincoln went on to draw, as he would do repeatedly, a distinction between freedom for all African Americans (which he advocated) and equality (which he did not). He would make this case with crude humor, as when he pointed out that opposing slavery did not mean he wanted a black woman for a sexual partner (a dig aimed at Kentucky Democrat and former vice president Richard M. Johnson). He would also make his argument with great fervor, as he did in the fifth debate at Galesburg, when he accused Douglas of “blowing out the moral lights around us, and perverting the human soul and eradicating from the human soul the love of liberty.” His political fortunes depended on it.

In the end, however, Lincoln’s rhetorical powers were not enough to bring him victory. And while it’s impossible to know just how much of a difference Douglas’s racial rhetoric made, it almost certainly mattered. The history of political campaigns in the century and a half since have given analysts plenty of reason to think that appeals to white racial solidarity play well with the white majority, even when those appeals are more subtle. Or not, in the case of a 2006 political commercial used against U.S. Senate candidate from Tennessee, Harold Ford, in which a white woman lasciviously suggests Ford give her a call.

And what of Frederick Douglass? Actually, years before Lincoln, it was Douglass who went to Illinois, seeking a debate with Douglas on the merits of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. As Douglass biographer William McFeely noted, “There can never have been much hope that Douglas would share a stage with a black man, let alone this one.” In August of 1858, Douglass joked that Douglas’s recent troubles in his own party dashed the former slave’s hopes that the Little Giant would bring distinction to a name so similar to his own, concluding that Douglas’s fate was ultimately “in the hands of Mr. Lincoln” (his first public reference to Lincoln). Upon Douglas’s death in 1861, Douglass said that while he could not rejoice in the death of anyone, “I cannot but feel, but in the death of Stephen A. Douglass [sic], a most dangerous man has been removed. No man of his time has done more to intensify hatred of the negro.”

As far as Lincoln goes, Douglass himself would probably have agreed with his ally Wendell Phillips’s famous early Civil War description of the obscure Illinois politician as “a first-rate second-rate man.” Yet as is often the case in the most hateful of assertions—indeed, why some statements are hateful—there was a grain of truth in Stephen Douglas’s charge that Lincoln was a “Black” Republican. The depth of Lincoln’s commitment to white supremacy was suspect in 1858 and only became more so with the passage of time (indeed, by the end of his life, when he considered enfranchising black voters, Lincoln broached the possibility of the very kind of equality he explicitly denied advocating seven years earlier). After Lincoln’s death, Douglass described Lincoln as “the white man’s president.” But he also said after his first meeting with the Great Emancipator in 1863 that Lincoln “was the first great white man in the United States that I talked with freely, who in no single instance reminded me of the difference between himself and myself, of the difference of color.” If this was praising him with faint damnation, it is praise many of us would be glad to receive.

It would be a mistake to draw a straight line from Frederick Douglass to Jeremiah Wright and from Abraham Lincoln to Barack Obama. For one thing, Wright and Obama had a closer relationship than Lincoln and Douglass ever did, and for all his incendiary rhetoric, Douglass was too much the politician to offer up the sort of provocations that are Wright’s stock-in-trade (e.g., that the U.S. government deliberately infects African Americans with the AIDS virus). Nor can it be said that Hillary Clinton or John McCain has ever been as blatant in her or his racial appeals as Stephen Douglas—though New York Times columnist Bob Herbert has skillfully deconstructed the subliminal sexual subtext of an ad McCain ran last summer that showed Obama juxtaposed against Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, and split-second images of the Washington Monument and Berlin’s Victory Column in all their phallic glory. Nevertheless, the 2008 presidential campaign has been notable for the degree to which politicians have explicitly tried to discredit opponents by calling attention to their supposedly extremist friends and allies. No figure has been more prominent in this game of guilt-by-association than Wright—and no topic has been more cynically exploited for political gain than race. We have come a long way, and yet a vision of society in which there is truly malice toward none remains an unrealized—impossible?—dream.

Further Reading:

The Lincoln-Douglas debates are available in many editions, including online; I have long used the user-friendly versions included in the first volume of the two-volume set, Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, published by the Library of America (New York, 1989), themselves drawn from the standard source, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy Basler (New Brunswick, N.J., 1953). On Douglass, see Philip S. Foner, Frederick Douglass: A Biography (New York, 1964) and William McFeely, Frederick Douglass (New York, 1991) as well as David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Baton Rouge, La., 1989) and James A. Colaiaco, Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July (New York, 2006). Douglass’s work is anthologized in the Library of Black America’s Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, edited by Foner and abridged and adapted by Yuval Taylor (Chicago, 1999). See also James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York, 2007) and Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Changed America (New York, 2008). Bob Herbert followed his column “Running While Black” in the New York Timeson August 2, 2008, with a revealing television analysis of the McCain Hilton/Spears ad on Joe Scarborough’s Morning Joe program on MSNBC on August 4 (it can be viewed on YouTube).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Jim Cullen teaches history at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York, where he serves on the board of trustees. He is the author of The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation (2003) and Imperfect Presidents: Tales of Misadventure and Triumphs, recently published in paperback by Palgrave-Macmillan, among other books.