These Names Had Life and Meaning

Students document antebellum African American civic engagement

The high-school students in the extracurricular Project Apprentice to History (PATH) in Beverly, Massachusetts, are not your typical honors students, yet their achievements are extraordinary. From their work on a project on African Americans in antebellum Boston, these students obtained a sense of connection to real people in history whose lives seemed at times ordinary and at other times heroic. The PATH students’ willingness to engage in hard work with primary sources gave meaning to the contributions of people who have either been forgotten or never before appreciated. (Click here to learn more about PATH.)

The research project focused on African Americans’ civic engagement through membership in voluntary associations. Many of these, such as the Boston Vigilance Committee and the Boston Anti-Man Hunting League, were abolitionist groups actively involved in the Underground Railroad, while other voluntary associations focused on temperance, prison reform, and other reform movements in the first half of the nineteenth century. The project began as a result of a fieldtrip W. Dean Eastman’s U.S. history classes took to the African American Meeting House on Boston’s Beacon Hill. The visit triggered questions about the role of Bostonians in both the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement. “I was wondering if there was a way to find out who the fugitive slaves were,” one student said, “and who, if anyone, helped them.” Another student was “interested in social divisions at that time period in Boston. Who were the ‘upper-class’ African-Americans? Who was in the ‘lower-class’?”

By ultimately combining all we could find on each African American citizen and group, we focused on the point where public and private history meet, where local history intersects with broader historical trends and events. The students compiled a database of cross-referenced demographic data from the U.S. Census, Boston city directories, and Boston tax records. They also digitized and indexed hundreds of articles from William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. Eventually, they published the results of their original research on the Web. And the testimony of the students themselves is indicative of just how meaningful the project was for them.

Central to the success of our project was close collaboration with libraries, museums, and archives, including the Boston Athenaeum, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the Boston African American Historic Site. In addition to providing essential records of various voluntary associations, these institutions allowed our students to see where and how much of the most important research into the American past is undertaken.

At early, before-school sessions at the Beverly Public Library, students continued the research they had started on the previous Saturday in Boston. Students printed copies of the original enumeration sheets from an 1850 U.S. census CD-ROM. Using blank census forms, they then began the process of transcribing and entering into a spreadsheet all of the individual demographic data from the African Americans that was listed. This painstaking process involved deciphering the handwriting of the census enumerators. “I definitely got a lot better at reading primary documents,” said Alison Woitunski, class of 2004. “You would be surprised at how difficult it is to read someone’s handwriting on paper that’s over 100 years old.”

This process also helped students develop research skills. “The most important skill I learned was how to conduct primary research,” Ryan Morse, class of 2004, said . “Beyond that I learned how to organize a really well-written paper, and to organize my thoughts to come out in the best way possible.”

From the 1850 census, our database expanded to include categories such as age, sex, race, occupation, literacy, value of real estate, and place of birth. The 1848-53 Boston city directories listed names, occupations, and addresses of adult residents of Boston. Prior to the 1848 directory, the list was segregated, making it easier to develop an initial database that included street addresses. Starting with the 1849-50 directory, it was difficult to tell the race of the residents. And, although the 1850 census expanded the categories of our database, it omitted the important category of street address.

We found an answer in the 1850 tax records at the Boston city archives. In these manuscripts all adult names were listed by address, occupation, and race. We photocopied and digitized the records for Beacon Hill and then transcribed the data into a table. Now we were able to link African Americans from the 1850 census with their respective residences. By combining city directories, the census, and tax records, we could trace the lives of nearly two thousand African Americans through 1848-53 using our database.

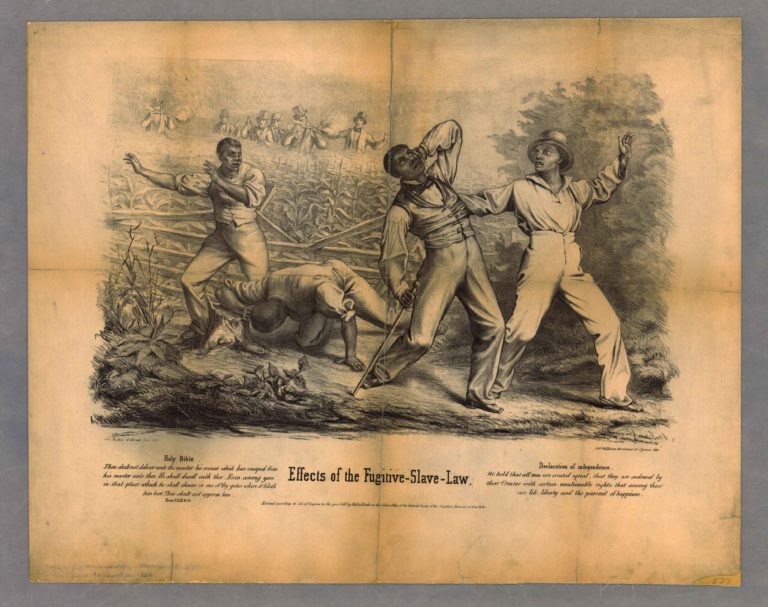

During the course of the project, students began narrowing their research to topics that could be answered through the database. What was the racial and gender composition of the members of the various abolitionist groups? To what extent had both slavery and the slave trade flourished in Massachusetts? How did segregation impact Massachusetts’s schools, marriage laws, and passenger train accommodations? We were particularly curious about the years 1850-53 because of the ramifications of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Who were the fugitive slaves living in Boston in 1850? Did the neighborhood population change in the ensuing years?

We found an invaluable source of information on voluntary associations in The Liberator. Students digitized nearly five hundred articles dealing with these groups between the years 1831 and 1855, discovering many names from our database appearing in these articles.

At the Massachusetts State House Special Collections, one of our students, Alison Woitunski, discovered an account book of the Boston Vigilance Committee listing fugitive slaves. From this account book she created a chart identifying both the fugitives and their benefactors. Again, many of these names could also be linked to our database.

At the athenaeum we discovered an 1852 map depicting every structure in the city. We began considering economical ways of accessing the database using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) technology. Having only a rudimentary concept of the capabilities of GIS, we enlisted the help of Roland Adams, GIS Manager for the City of Beverly, and the possibilities became clear. GIS integrates maps with data, so that points on a map are designated to correspond to a database. Under Adams’s direction students arranged the information from the database into GIS format. Through careful research comparing a modern GIS map to the 1852 map, students were able to match parcel ID’s from the Boston Tax Assessors Office to the Beacon Hill addresses in our database. Now by clicking on a particular building on the modern-day map, one could see who was living there in 1850.

The culmination of the project arrived when students presented the results of their research at the Downtown Boston Harvard Club on February 9, 2004, before historians, archivists, and their parents and peers. Of the project, Alison Woitunski said, “[L]ooking back, I am not quite sure how I managed to be at PATH meetings at 6:30 A.M. or spend so many Saturday afternoons doing research in Boston, but I’m glad that I did.” Molly Conway added, “[O]ne thing I learned from this experience is that history is about finding the truth in what happened; when we used the Latin word for truth, veritas, we meant it also as a virtue.”

Online visitors may now access the resources developed by the students in PATH by visiting our Website.

This article originally appeared in issue 5.3 (April, 2005).

W. Dean Eastman teaches history at Beverly High School in Beverly, Massachusetts, and has been the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the Disney American Teacher Award (1991), Harvard University’s Derek Bok Prize for Public Service (2000), and the Preserve America Massachusetts History Teacher of the Year Award (2004).

Kevin McGrath is a library teacher at Newton North High School in Newton, Massachusetts.