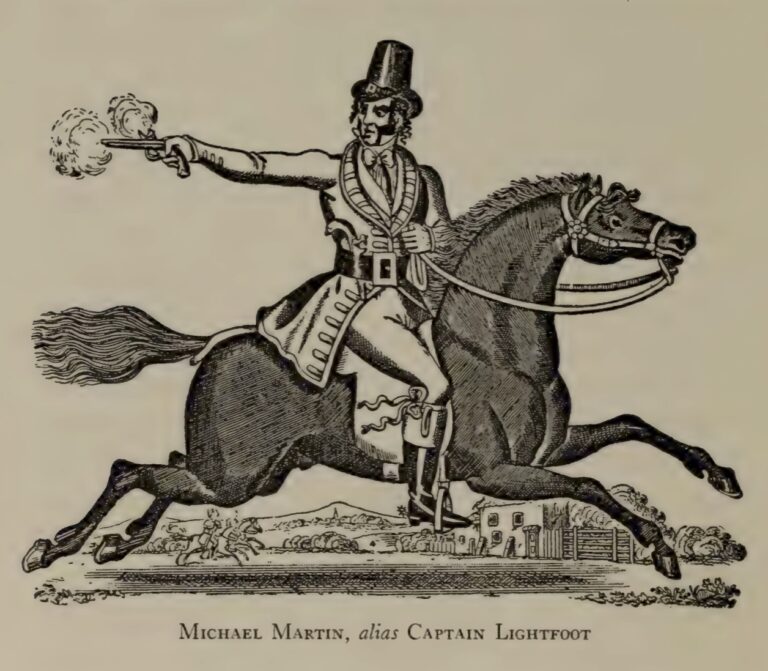

People today who have heard the stories of Captain Lightfoot and Captain Thunderbolt may be disappointed to learn that not only was “Captain Thunderbolt” never a resident of New England, but that he likely never existed at all, except in the fertile mind of Michael Martin. More amazing than the adventures of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is the story of what Michael Martin, condemned to death, did in prison in October and November of 1821. Within these two months, Martin created a heroic narrative for himself, and placed it firmly in the tradition of Irish outlaw lore.

Moreover, during these same two months, Martin and his outside accomplices devised a prison escape attempt that was highly technical—and which nearly worked. Martin was secured within his cell by leg shackles chained to a ring in the center of the room. Somehow, he was supplied with a crude saw, which he used to file a gap through one the links of the chain of his shackles. His shackles were inspected weekly, but he disguised the gaps by mixing ashes and wax to match the color of the chain. One day, when his jailor brought him his meal, he feigned weakness and asked the jailor to pick up something he had dropped. Martin then knocked the jailor over the head, slipped his shackles off the chain to the ring, and rushed out the open door. He pounded the locked outside gate until it burst open, and then ran across a field. However, there were still irons on his legs, and he was quickly chased down and subdued.

The sophistication of Michael Martin’s escape attempt suggests that he was very familiar with prison routines, yet there was no mention of any prior jailings in the account he gave to Francis Waldo. It can be conjectured that he had once been imprisoned in Ireland, where he had the time and access to collect or create tales of adventurous robberies, which he then offered to Waldo as the story of Captain Lightfoot and Captain Thunderbolt. As entertaining as those stories are, they hardly compare to the inventiveness and daring that Martin displayed in the space of two months, while waiting to be hanged. Michael Martin’s escape attempt failed, but his efforts to mythologize himself were a wild success.