Tocqueville, Falling for America

Alexis de Tocqueville had a bad experience at Niagara Falls. Crawling onto a ledge behind the cataract, pressing his face against the cliff as the river fell from above, it was hard to breathe. The wind blew hard in the narrow passage between the sheet of water and the cliff. Sometimes “the blinding torrent of water” hit his face and the air felt thin. It was night and the darkness was “deep and terrifying” and meant that he couldn’t see the bottom of the chasm below him. The flickering moonlight was just enough, he said, to illuminate the “vast chaos that surrounds you” (when an entire river passes over your head) before leaving you again “to the darkness and din of the falls.” On his spit of rock, the iridescence of the falls and also the steam rising in a cloud from the abyss “envelop[ed] everything in a suspect white light.” A nocturnal rainbow above the mist looked like any other rainbow except that it was perfectly white. I know of one other vision of a nocturnal rainbow from the 1830s and it is equally frightening: the narrator of Edgar Allen Poe’s story “Berenice” becomes obsessed with his beloved’s teeth which appear to him, even in her absence, as a “white and ghastly spectrum,” overreaching “the wide horizon as the rainbow.” They are not unlike the all-consuming white spectrum that Tocqueville sees across the maw of the Niagara cataract.

“I assure you,” Tocqueville writes home to a friend, “that there was nothing at all amusing about the spectacle before us.” Needless to say, most travelers to America in the nineteenth century responded differently to Niagara Falls. The Irish poet Thomas Moore said the sublime view from below produced a sense of “delicious absorption” in nature that brought him closer to God, but it is just the feeling of absorption that Tocqueville feared. It is not hard to see that Tocqueville’s experience behind the “torrent” of the falls recalled to him his darkest feelings about the “democratic torrent” of the times that seemed to be “[sweeping] everything along in its course” in ways that aristocrats like himself could no longer resist. It was too hard to hold one’s ground when the progress of democracy was “universal” in its sway and when a “single current” of public opinion and thought “command[ed] the human spirit.” “Immersed in a rapidly flowing stream,” he writes in Democracy in America, “we stubbornly fix our eyes on the few pieces of debris still visible from the shore, while the current carries us away and propels us backward into the abyss.” In a democratic culture, claims to social or political distinctions are left behind as the landmarks of a shattered past while the individuals that survive it are “beaten onwards by the heady current which rolls all things in its course.” In America, the culture of sameness and “common obscurity” could seem as suffocating to Tocqueville as the “humid obscurity” that scared him from within the enveloping mist of the falls.

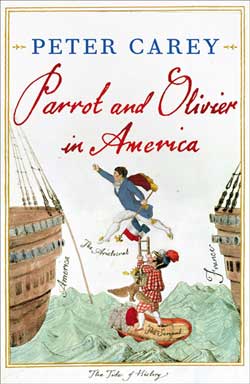

Tocqueville’s visit to Niagara inspires the climactic scene in Peter Carey’s remarkable novel, Parrot and Olivier in America, modeled on Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont’s travels in America in 1831. Like Tocqueville, Olivier de Clarel de Barfleur de Garmont goes first to Albany for a Fourth of July celebration and then to see the falls, except here they are Kaaterskill Falls in the Catskills, if only because they give Olivier the chance to remark, too, on the artist Thomas Cole who painted them around that time. Carey’s novel is deeply concerned with the possibilities for art in a democracy and also with the visual expressions of democracy that emerged within the new markets for art that supported them (but more on this in a moment). In Albany, Olivier finds, as Tocqueville might say, the “image of democracy itself” in the Independence Day parade of printers, mechanics, carpenters and other members of the trades and associations of the city bearing the badges of their professions. It lacks the martial “splendor, imperium,gloire” that would distinguish a procession in France and, to be honest, for an aristocrat, a float as big as an opera stage with a printing press turning off copies of theDeclaration—an eagle soaring on top of the whole insipid business—finally seems unthinkable. But, in the public reading of the Declaration and the return of a nation to the moment of its birth, “there was something deeply felt and truly great” and Olivier wonders if it might be possible to live his life “completely careless of how democracy might harm [him]”—to give way, that is, to the progress the parade represents and just be “one of the rivulets—nay, streams—that make the river of the people roar” (349-350). If only, Olivier says, the celebrations had stopped there: a lawyer steps up to deliver a Fourth of July oration and Olivier’s response is just the same as Tocqueville’s in Albany, since Carey takes his language directly from Tocqueville’s letters as they appear in George Wilson Pierson’s 1938 Tocqueville and Beaumont in America. The lawyer’s boorish, bombastic “harangue,” rehearsing the history of every single country in the world (which he names) in order to place America at the center of the world, makes clear that the revolution and “ascent of the majority” the day marks also marked, maybe most of all, an aesthetic revolution in the history of taste. “What makes democracy bearable?” Olivier asks (351)—and then travels on to the falls.

Olivier de Garmont is born in 1805 into a family of Norman nobles who manage to survive the French Revolution, though with varying degrees of depression and perversity after the Terror; the guillotine “cast[s] its diamond light” on the superannuated scenes of Olivier’s childhood at the Château de Barfleur (16). His mother keeps the desiccated corpses of family pigeons killed by peasants and sings laments for her lost king; Olivier, hearing them, gains a primal sickening knowledge of his mother’s attachments and the obscenity of the Revolution (which exasperates his asthma). When the Bourbons are restored to the throne, the family recovers some of its status, but after the July Revolution of 1830, Olivier, now a young lawyer at Versailles, is caught between loyalty to his family and to King Louis-Philippe, who has bourgeois sympathies and tenuous claims to the throne. The kings who follow upon Napoleon’s 1815 defeat are pitiable in the novel; royalty becomes showy and flagrant as it becomes merely symbolic. Charles X is “pigheaded,” believing that he can secure his power by restricting the rights of his citizens. But when he is overthrown in 1830, he sneaks past Olivier and the royalists who are defending his palace and slinks out of Paris “mud-smeared like so much shameful shit across the royal escutcheons” (84). Olivier, now under suspicion by the liberal government, leaves for the United States to conduct an official study of its famous penal system, just as Tocqueville and Beaumont did. Drawn to the lectures of François Guizot, who argued that the progress of democracy was irresistible and could not be turned back, Olivier wonders whether he will “drown swimming against the tide of history” or whether an aristocrat’s distinctive forms of understanding and belief can be made relevant to the present age (71). Could a democracy tolerate him?

In America, Olivier falls in love with Amelia Godefroy, the daughter of a governor of the Wethersfield Penitentiary in Connecticut, and it is at the insistence of Amelia’s father that he goes to Kaaterskill Falls. Neither Tocqueville nor Beaumont fell in love in 1831 (frustrated by the chastity of American women, they had no love affairs either), so Amelia is one of Carey’s many inventions. But Tocqueville does love Connecticut as much as Olivier because, for both—historical actor and character—the towns of the state represent model units of local self-governance. Run by their town meetings and voluntary associations, they show Tocqueville democracy at its most vital and quaint, perhaps because the stakes remain small enough to be particular, and aristocrats like to be particular. In the novel, the people of Wethersfield move to build roads and raise taxes for the school, but they also deliberate on whether to patent a Wethersfield onion, and the participatory nature of it all (or else the onion) brings tears to Olivier’s eyes. If “the great lava flow of democracy came inexorably toward us,” and if we went with the flow, then maybe the future could feel as careless as the Godefroy onion fields growing half-wildly in the deep alluvial soil of the Connecticut valley. “Your town meeting rather shook me to my bones,” Olivier tells Amelia. “I am still reverberating” (262). But he blushes and knows when he says it that he is talking as much about her effect on him as the meeting’s. It becomes increasingly obvious that the irresistible power of democracy—even the unsettling way it creates a “restlessness of spirit” and social activity and a craving for continual excitement—feels a lot like falling in love. “I thought, Miss Godefroy. Restlessness of spirit” (215).

It is only when Olivier stands on a bridge of rock behind Kaaterskill Falls, where Amelia’s father had brought him (crying into his ear, “Now you are American”), that falling in love, with democracy or Amelia, seems more like a self-annihilating plunge—a falling away into “a terrifying and foreign obscurity” (354). Olivier’s asthma returns: “There was no air in America,” he says, “only this great suffocating mass which would wash me clear away. I pressed my mouth against the rock behind me, and so could almost breathe” (354). At the falls, he remembers the July Revolution, just as Tocqueville did at Niagara Falls, when visions of the civil war at home seemed to slide, as Tocqueville writes, “between me and my surroundings,” so that only his attachments to an aristocracy that has outlived its use seem to save him from giving way to the “mass.” Olivier tells us that the trip to Kaaterskill Falls gives Mr. Godefroy a new excuse to praise the artist Thomas Cole, who had painted them, and whose picture Autumn on the Hudson hangs ostentatiously in the Godefroy foyer. So we come to picture the waterfall that sickens Olivier as if it were a Thomas Cole painting and then wonder whether—in the face of such a garish picture—we should be horrified too. Kaaterskill Falls are the beginning of the end of Olivier’s engagement to Amelia. He couldn’t bring her home to his mother. She loves “innovation” too much. She incorrectly uses the dewhen she addresses him as “de Garmont.”

So who, in Parrot and Olivier in America, is Parrot? Olivier’s friend Thomas Blacqueville, another Norman aristocrat, is set to travel with him to America, but the great ingenuity of Carey’s novel is to kill off his Beaumont before they set sail. Instead, Olivier (really a composite of Tocqueville and Beaumont) is accompanied by John Larrit, a.k.a. Parrot, an irreverent English engraver twenty-four years his senior whose first-person narration of the journey alternates with Olivier’s own. Olivier has bad handwriting, as Tocqueville did—Leo Damrosch tells us that Tocqueville called his illegible scrawl crottes de lapin (“rabbit turds”)—so Parrot acts as Olivier’s secretary, but also spies on him and reports back to the Comtesse, his Maman. Parrot has a history we learn slowly: when his father, a journeyman printer, is arrested for forging banknotes, Parrot (then orphaned at twelve) finds himself in the hands of a counter-revolutionary Frenchman (and the Comtesse’s lover), the Marquis de Tilbot, who abandons him on board a ship of convicts bound for Australia. Years later Tilbot returns for Parrot, who joins him on an expedition to engrave Australian plants for the Empress Josephine, and then follows him to Paris where he lives as his servant and trades in botanicals. By the time Parrot leaves for America with Olivier, we know that this bawdy, cocky mimic (“Parrot”), with his broguey idiom, is capable of illustrating whatever he sees as he sees it and will give us a fair account of the aristocrat he serves.

For Parrot, Olivier is Lord Migraine and Little Pintle d’Pantedly, who is fatefully unadapted to the energies of America, where people can start over as quickly as they can burn their homes and collect insurance on them. For Olivier, Parrot is a presumptuous copyist who thinks his time is his own (“His time? This was a very modern concept he had learned” [319].) Coming to terms with America is also Olivier’s way of learning to live with Parrot, who he comes to love a little too, and with a new set of relations defined by what we do, not what we are. There are no masters in America, just “bosses,” and sometimes they and their “help” shoot the breeze. If all this “malodorous égalité” depresses Olivier “awfully,” it is because he believes it is the opposite of his liberty to resist it and also because the restless, agitated society around him feels always, tyrannically, the same (199). “Variety is vanishing from the human species,” Tocqueville writes; he also means that democracy takes us beyond a political society, defined by its differences in opinion and thought, toward a commercial society that acknowledges only the differences a market can make. But, in the novel, Parrot finds his freedom in the market, where he eventually sells his engravings to great success and buys a house with his mistress on the Hudson. An undiscriminating public is less threatening for the artist who aims to please it.

Often Olivier and Parrot clash for aesthetic reasons; they can never agree on what constitutes art when they see it, since Olivier is never convinced that a democracy can produce it. Art in a democracy, says Olivier, “suit[s] the tastes of the market, which is filled with its own doubt and self-importance and ignorance, its own ability to be tricked and titillated by every bauble” (379). By the end of the novel, Parrot shows us how easily art in America accommodates itself to commercialism; art becomes a way of living, but its professionalism is never far from hucksterism and debasing forms of trade. Scenes of his mistress, Mathilde, painting portraits are also scenes of prostitution (her clients “ask her price” and then she sets out to “do” them). In New York, Parrot becomes the business partner of Algernon Watkins, an English artist who was also a forger during the French Revolution, by printing and marketing the pictures he engraves. Watkins is a fictionalized John James Audubon and his goal is to make the greatest book of life-size colored bird prints the world has ever seen. But really, Carey has divided the historical figure of Audubon between Watkins and Parrot, the artist and entrepreneur, since Audubon was both. Audubon’s The Birds of America was as much a marketing phenomenon as an event in the history of engraving, and Parrot’s prospectus for Watkins’ book of the same name reproduces Audubon’s pitch and secures his same subscriptions from European royalty. Audubon applied glazes to his birds to intensify the brilliance of the variegated colors of paint which he densely layered for a dazzling, animating effect. Parrot’s birds have a similar gloss, and the sample he proudly shows Olivier reminds the aristocrat of the surface splendor and glare of Thomas Cole’s painting. “It was nothing much more than a circus bird,” Olivier says, “but [Parrot] stood before me full of hope, like a boy in a fairy story, off to make his fortune in the world” (327).

But it is finally Mathilde’s later pictures that baffle Olivier most: abstracted landscapes made of colors and glazes she paints for pleasure, not business, and that experiment with the “luminous mystery of New York light” (376). “The paintings are awful,” Olivier says (377). Like luminist paintings of the mid-nineteenth century (by John Frederick Kensett or Sanford Robinson Gifford), Mathilde’s effort to “[paint] only the light” of a broad open space (246)—to create, that is, the effect of a diffused atmosphere—may feel to Olivier like being bathed in the all-enveloping iridescent haze of Kaaterskill Falls. The abstract paintings, which depict nothing in particular (“They are not exactly paintings”), may be the aesthetic correlative of the generalizing potential of democracy to softly permeate the total world around you (377). For Parrot they are the sign of the future of art, a lustrous, radiant vision of the New York horizon Mathilde sees from her house on the Hudson; but Olivier is near-sighted and can’t make them out. His myopia is a constant source of slapstick ridicule in the novel—he really can’tsee—and modeled on (what else?) Tocqueville’s own legendary near-sightedness that Beaumont describes during their travels in America: “He is very nearsighted, so when he came to what he thought was quite a narrow river, he did not hesitate to swim across. But he was wrong: in fact, the river was so wide that he was dead tired by the time he made it to the other bank.” The horizon is always receding and because Tocqueville misjudges the distance he would have to go to get there, he comes “close to drowning.”

Mathilde’s paintings are also a sign of American exceptionalism, since she tries to paint “New York” light; but Olivier says, “the same sun shines on everything” (377). Parrot believes that America is a place of progress that has superseded the antiquated world of France they left behind and that Olivier will retreat to in the end. Parrot has the last words of the novel, and they are canny because we learn, finally, that this story of democracy and progress is merely his own since he has written the whole of it (of course! Olivier doesn’t write because his handwriting is bad). Parrot looks into the future and says, in his final dedication to Olivier, that his fears have been “phantoms”: “Look,” he says, “it is daylight . . . There is no tyranny in America, nor ever could be. The great ignoramus will not be elected. The illiterate will never rule” (381). Still, as readers living now in the future he prognosticates, we are not so sure that the “great ignoramus” has not been elected, or won’t be, and anyway, Parrot is just a parrot. Parrot’s insistence on America’s democracy can never be final, because we know we’ve lost the sense of difference that Olivier made.

Further Reading:

Peter Carey draws on George Wilson Pierson’sTocqueville and Beaumont in America (New York, 1938). For more on Tocqueville and Beaumont’s American travels, including their letters, travel notebooks and sketches from 1831, see Olivier Zunz, ed., Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont in America: Their Friendship and Their Travels, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Charlottesville, 2010). Tocqueville famously describes his experience of democracy in Democracy in America(1835-1840); for critical views, see Sheldon S. Wolin,Tocqueville Between Two Worlds: The Making of a Political and Theoretical Life (Princeton, 2001) and Leo Damrosch, Tocqueville’s Discovery of America (New York, 2010). On John James Audubon as an engraver and entrepreneur, see Annette Blaugrund and Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., eds., John James Audubon: The Watercolors for The Birds of America (New York, 1993) and Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American (New York, 2004).

Elisa Tamarkin is associate professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author ofAnglophilia: Deference, Devotion, and Antebellum America (2008).