Tragedy, Welfare, and Reform: The Impact of the Brooklyn Theatre Fire of 1876

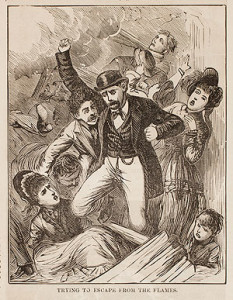

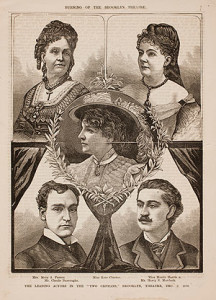

December 5, 1876, was the second night of the Brooklyn Theatre’s production of The Two Orphans, a popular French melodrama that had taken New York by storm. The Brooklyn version of the show had received rave reviews too, with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle calling it “a near approach to the common idea of perfection,” while Kate Claxton, a rising actress seemingly on the verge of stardom, played Louise, one of the titular characters. Perhaps because of these attractions, nearly 1,000 people, about two-thirds the theater’s capacity, braved the bitter winter cold to see the show. The spectators and actors alike found themselves at the center of one of the deadliest fires in New York history (fig. 1).

The infamous Brooklyn Theatre Fire became a legend in theatrical circles, spawning popular songs and melodramas and making Claxton one of the most popular celebrities of the day. Yet the Brooklyn Theatre Fire also left a longer-lasting legacy. After an investigation into the causes of the fire revealed negligence and lax conditions in most theaters in Brooklyn and New York, the local press, led by the New York Mirror, campaigned for regulations that helped transform the physical space of the American theater. Moreover, the voluntary relief efforts to aid the “destitute widows and orphaned children” encouraged municipal reformers in Brooklyn to challenge the city’s existing charity structures and eventually end public outdoor relief in Brooklyn, a move that transformed the nature of welfare in the nineteenth-century American city.

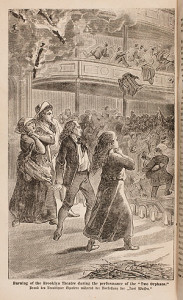

On this December night, when a cross-section of Brooklyn society turned out to see The Two Orphans, the primary concern was whether Claxton and her fellow actors would be able to capture the audience’s imagination. The play proceeded without incident until the beginning of the last act, shortly after eleven o’clock. A piece of painted scenery, improperly secured by the stagehands, had strayed too close to one of the gaslights used to light the theater and caught fire. The blaze spread rapidly, and it seems the actors were the first to become aware of the danger. Sensing that a panic would be dangerous, the actors attempted to continue with the play amid a growing sense of unease. Claxton herself was forced to break character and assure the audience that “There is no fire. The flames are part of the play” (fig. 2).

Yet almost immediately as she reassured theatergoers, pieces of flaming debris began to fall onto the stage, leading the actors to scatter and causing a full-fledged panic. Though the largely middle-class patrons seated on the main floor were able to easily escape, the working-class men and women in the cheapest seats, the top-level family circle, and parquet seats nearest to the stage were less fortunate. Hundreds of people crammed the narrow stairways down to the main exit, and dozens were trampled as the panicked throng attempted to reach the exits even as the fire spread to the theater’s upper levels. One witness reported to the New York World that he saw “women screaming, pushed aside by rough-looking men and boys… I saw a large rough man who appeared to be blind from excitement jump over the heads nearest to him and come down on the face of a fallen woman. The sight sickened me” (fig. 3).

Only twenty minutes elapsed between the first signs of fire and the immolation of the entire building, hardly enough time to evacuate the theater. Lingering flames prevented the fire department from entering the building until the early hours of the next morning. Though it would take weeks to sort through the wreckage, it was immediately clear that the fire had caused casualties on a scale previously unimaginable. A coroner’s report listed 283 confirmed fatalities, though some reports place the death toll as high as 350. Among these were several actors in The Two Orphans, though Kate Claxton survived; police found her wandering about in a state of shock the morning after the fire, still clad in the flimsy dress from the performance.

Regardless of the number of dead, the Brooklyn Theatre Fire was the deadliest fire in a public building in the nation to that point, and is still the third deadliest in American history (behind the 1903 Iroquois Theater Fire in Chicago and the 1942 Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire in Boston). The scale of the disaster staggered Brooklyn, the nation’s third-largest city (the consolidation of New York City would not take place until 1898), a place that styled itself as “the city of churches and homes.” While the police began to gather survivors at the First Precinct station house on Washington Street near the back of the theater, the coroner’s office and the fire department began the arduous task of removing the charred remains of the deceased from the theater’s ruins. Over the next few days city officials were besieged by families of potential fire victims seeking news of loved ones, or just as often, temporary financial support. City Mayor Frederick W. Schroeder, a well-to-do cigar manufacturer elected on a pledge to curb city spending, admitted ruefully that he had “drawn from the city treasury” to meet the demands of aid-seekers. Similarly, church officials, charity aid workers, and even agents of Brooklyn Democratic “boss” Hugh McLaughlin provided money indiscriminately to those affected by the fire. The entire system was, in the words of Brooklyn Theatre Fire Relief Association member Simeon Chittenden “entirely disorganized … [causing] an undue strain on public finances.”

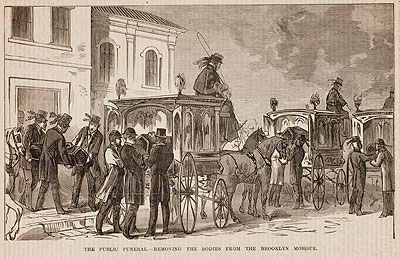

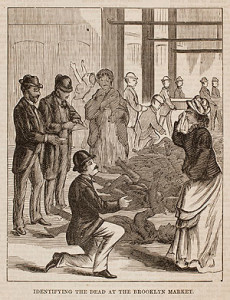

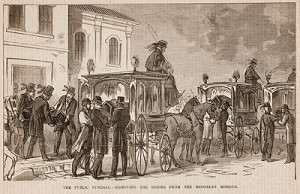

Furthermore, there was the problem of identifying the bodies and determining what to do with them. The coroner set up viewing galleries so that families of potential victims (and curious spectators) could see many of the remains and items that could possibly be identified (fig. 4). 180 bodies were eventually claimed in this way. The remaining 103 victims, most of whom were unidentifiable or unclaimed, were buried in Brooklyn’s famous Green-Wood Cemetery in a mass grave during a public funeral (fig. 5). Later, the city would erect a thirty-foot-high obelisk at the site to commemorate the victims. The obelisk still stands today, and is the only visual reminder of the tragedy in Brooklyn (fig. 6).

As bodies were still being pulled from the rubble, the local paper the Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran an article chronicling widespread dishonesty among supposedly “bereaved” families affected by the fire. Mayor Schroeder cut off public relief for fire victims immediately. Conscious that legitimate relief was required, Schroeder instead utilized the occasion of a memorial service for the deceased on December 12 to call for the creation of a private organization that would “systemize the work [of relief] through one central organization.” The privatization of disaster relief in Brooklyn was part of a larger effort by municipal reformers in the 1870s to refine urban welfare, giving the administration of aid to upper-class “experts” with experience managing charitable organizations. Schroeder and his fellow reformers feared that if the machine-controlled Brooklyn Common Council were given charge of fire relief efforts, “Boss” Hugh McLaughlin would use the funds to buy political influence while the “virtuous poor” would be ignored. Given the scale of the disaster and the severity of the 1876-77 winter, Schroeder and his colleagues demanded that aid efforts be controlled by experienced administrators. Though the privatization of Brooklyn fire relief seems at odds with the narrative of urban reform in the Gilded Age, the privilege granted to expertise and the fear of the power of the urban machine puts these efforts in line with similar reform efforts of the time. At a public meeting at the Brooklyn Academy of Music a few days before Christmas, that organization, the Brooklyn Theatre Fire Relief Association (BTFRA) came into being. The brainchild of Ripley Ropes, a wealthy merchant and the president of the Brooklyn branch of the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (AICP), the BTFRA followed procedures developed by the AICP to streamline relief efforts. All prospective aid-seekers were forced to visit BTFRA offices and undergo a home visitation before receiving relief, and recipients faced strict accounting procedures and a number of other anti-fraud measures afterwards. Appealing to the hearts and pocketbooks of prominent Brooklynites, headlining speaker Henry Ward Beecher explicitly cast relief efforts as a struggle against creating more public dependents. “How will you provide for those whom God has made your guest?” Beecher asked, demanding to know if the elite of Brooklyn would let the fire victims and their families “fall into the degrading and brutalizing position of public dependence.” Donations streamed in from Simeon Chittenden, Seth Low, Henry Evelyn Pierrepont, and other rich Brooklynites, as well as hundreds of smaller donations from all over Brooklyn and beyond. Indeed, theater companies nationally took up the cause of the disaster. Companies from as far away as Charleston, South Carolina, held impromptu fundraising performances in urban theaters across the country, with the proceeds donated to fire relief. By the end of 1876, the BTFRA had over $28,000 in their account to distribute for the relief of fire victims and their families—particularly widows and orphans, the stated focus of the BTFRA’s relief efforts.

Ripley Ropes recruited many other wealthy Brooklynites to join him on the board of the BTFRA. Daniel Chauncey, president of the Mechanics’ Bank, served as treasurer. More importantly, Ropes’s close friend Reverend Alfred Putnam, the pastor at Brooklyn’s First Unitarian Church (where Ropes was a member), became the association’s secretary and managing director. Putnam was responsible for the day-to-day operation of the BTFRA and became the organization’s “face” to the public. The volunteer “visitors” who affirmed a family’s suitability for relief were drawn from the ranks of the AICP’s staff, which had experience in sorting out the “worthy poor” from the unworthy residuum.

Indeed, the very structure of the BTFRA seemed to be skewed against aid-seekers from the very beginning. This is perhaps best observed in the rigorous screening process that potential relief recipients were forced to undergo. First of all, most men were excluded from making a claim unless they could prove that they, through reason of age or disability, relied upon the income of their wife or child. Most men who applied for aid were summarily dismissed, revealing the BTFRA’s lack of understanding of the economic structures of families in the city’s working class. BTFRA clients needed first to provide the BTFRA with a reference attesting to their character and to the fact they lost a relative who provided for them and their family. Then, “their family circumstances were investigated by case workers who spared no pains to acquaint themselves with the character and needs of the numerous applicants and with the merits of their claims.” If found worthy by the visitors, the Executive Committee would set a biweekly stipend appropriate for the family’s lost income. Visitors kept copious notes about each home, and particular attention was paid to family arrangements and suspicions of alcohol consumption. The visitor for each ward would also be able to adjust the biweekly stipend at their discretion (and often did). These adjustments most frequently drew letters of complaint from aid recipients.

During any step along the way, applicants could be judged ineligible, and many of the other charities took it upon themselves to police the distribution of relief. For example, when Reverend S.B. Halliday, Beecher’s assistant at Plymouth Congregational Church, heard that the mother of 22-year-old Irish laborer William Kennedy had applied for aid, he wrote to the Executive Committee to warn them that “Mrs. Kennedy is addicted to drinking … no money should be given to the mother.” In another case, the visitor assigned to the widow of vegetable seller Jacob Allen felt “she is not telling the truth [about her lost income] and [he] could not recommend any help.” Indeed, there was a near-obsessive fear among members of the BTFRA that their assistance was not going to the most “worthy” families. Robert Foster, the president of the Union of Christian Work, wrote to Rev. Putnam on January 4, 1877, nearly a month after the fire, to warn him, “It is possible some of [the aid-seekers] have not been so far purified by fire that they will not falsify.”

Yet in spite of such a fear of fraud, the BTFRA was motivated by a genuinely humanitarian impulse, and the organization proved remarkably effective in aiding victims of the theater fire. Of the 278 confirmed victims, the BTFRA ultimately provided an average of $250 per family to 188 families over the course of its two-and-a-half years of existence. Though the audience the night of the fire was a mixture of middle and working-class patrons, the dead had been disproportionately working-class immigrants, and they received the bulk of the BTFRA’s financial support. Only a handful of families were rejected as being unworthy; for the most part, families not receiving aid either did not ask for it, or were rejected on the grounds of having other means of support. Moreover, there seemed to be little ethnic or racial prejudice in determining who received aid. Families of Irish descent made up nearly a third of those receiving aid, while immigrant families from Germany, Italy, and Poland were also represented on the BTFRA’s relief rolls. The children of the only two African American victims of the Brooklyn Theatre Fire, William and Hannah Brown, were among the last people to be taken off the relief list; even after they moved to Oswego, New York, to live with an aunt they continued to receive a biweekly stipend. The Executive Committee was often willing to hear arguments of aid recipients who felt their stipend was wrongly reduced or discontinued, and in at least a handful of cases restored payments if family circumstances changed.

There were certainly missteps as the BTFRA groped with the scale of the disaster. For example, the BTFRA began by providing every family a $20 stipend every two weeks, a sum that the BTFRA Executive Committee later acknowledged “would have completely depleted our treasury within one year.” Generally, however, the BTFRA proved to be an effective relief measure. Recipients of relief were genuinely grateful for the aid they received. Mary Jackson, whose husband, Robert, perished in the theater fire, was one such recipient. The mother of eight children (one of whom was born after the fire), Jackson became a media sensation in the wake of the disaster. Journalists hungry for stories of heartbreaking tragedy reported on Jackson endlessly in the weeks after the fire, and in many ways she became the face of the Brooklyn Theatre Fire for Brooklynites and people around the nation. She remained on the books of the BTFRA for two years, and credited the BTFRA with her salvation. The aid she received, she wrote to the Executive Committee, “allowed me to provide for my children without sacrificing my womanhood … I will remain forever in the debt of the fine citizens of Brooklyn.”

As time passed, and donations to the Brooklyn Theatre Fire Relief Association began to dwindle and the number of recipients decreased, the organization moved to dissolve itself. On March 17, 1879, the BTFRA issued a check for $317, the remaining money in its treasury, to the widow Jackson. A week later, on March 25, the Executive Committee presented its final report to the public, declaring “it is believed that time has been given for nearly all of the families to find some other resources which may enable them to meet the necessary expenses of life.” Reverend Putnam and the BTFRA had distributed nearly $50,000 to Brooklyn families affected by the fire in a little over two years. With the dissolution of the BTFRA, the Executive Committee felt that “the most tragic and impressive event in the annals of Brooklyn” had been finally overcome, thanks to the charity of citizens from around the nation and overseas, as well as the efforts of the “best men” making up the BTFRA.

After seeing the success of the BTFRA in solving the problems of disaster relief, however, Putnam and Ropes began to wonder whether private charity would be a more appropriate means of dealing with all of the city’s destitute. After being appointed to the state Board of Charities, Ropes recruited Putnam to assist him in an investigation of the structure of relief in Brooklyn, and their findings horrified middle- and upper-class citizens. Ropes and Putnam revealed that Brooklyn’s spending on public welfare had climbed steadily. Between 1872 and 1877, relief spending increased from $95,771.43 to $141,207.35; moreover, relief rolls had increased dramatically in that time, with an estimated 50,000 people receiving relief in 1877, double the amount from five years earlier. Part of this increase was surely due to Brooklyn’s growth during the 1870s. The city’s population grew from just under 400,000 in 1870 to 566,000 at the end of the decade. Moreover, the Panic of 1873 introduced a further element of economic uncertainty that surely added to Brooklyn’s relief rolls. Yet, Ropes and his colleagues ignored these structural causes and instead saw the increasing number of aid recipients as a challenge to Brooklyn’s image as “a city of homes and churches.” At a meeting of Kings County Supervisors, Ropes described Brooklyn’s public relief system as “exceeding expensive” and “encouraging to pauperism.” Ropes proposed that outdoor relief should be limited to coal, with private charities taking responsibility for issuing any direct financial aid. Ropes also suggested that nearly 46 percent of outdoor relief in the current system went to “expenses” paid to the Supervisors and the Charity Commissioners—charges which the Kings County Charity Commissioners Thomas Norris and Bernard Bogan and members of the Board of Supervisors (led by Supervisor John Byrne) angrily denied, instead accusing Ropes and Putnam of trying to “punish the worthy poor.”

The same split between the genuine desire to aid the poor and the suspicion of charity that lay at the center of the BTFRA similarly animated those in favor of abolishing outdoor relief. The Brooklyn Eagle spoke for many when it outlined the objections to outdoor relief. In an editorial dated December 18, 1877, the Eagle argued that the outdoor relief system encouraged pauperism, hurt private charity efforts, was too expensive, served the unworthy poor rather than those most deserving and, most seriously, “had a political side which [was] unconditionally vicious.” Democrats like Bogan and Byrne who had relied on “Boss” McLaughlin’s machine for election were portrayed as abusing public funds to serve the interests of McLaughlin while at the same time encouraging the virtuous poor to fall into permanent pauperism.

In contrast, men like Ropes and others who supported his proposals, including key members of the BTFRA Executive and Financial Committees, including Putnam, Mayor Schroeder and future mayor of both Brooklyn and New York City Seth Low (fig. 7), portrayed themselves as seeking to remove politics from the distribution of outdoor relief—and in the process “save” the worthy poor from pauperism. Their accusations were supported by an investigation by the Eagle into the Commissioners of Charity that led them to brand outdoor relief efforts “a sham” and a “damnable fraud.” Later that month, Winchester Britton, former district attorney of Kings County (no relation to the author of this article), advised the Board of Supervisors that the program of outdoor relief was illegal in the form that had been established by the supervisors. Despite vociferous opposition by members of the Board of Supervisors and the Charity Commissioners, the board formally voted 17-12 to eliminate appropriations for outdoor relief from the county budget in July 1878. Frequent attempts to revive the system were made in the next few years, but never got very far in the face of adverse public opinion.

What happened to the nearly 50,000 Brooklynites who had been receiving outdoor relief? It is difficult to say. Despite reports by Seth Low and others that private charity had more than met the needs of the city’s poor, it is clear that their suffering had not been eased. Historian Michael B. Katz notes an increase in the number of children handed over to asylums and agencies as well as a general increase in the number of petty larcenies in the years 1878-1880. He suggests that the money saved by the elimination of outdoor relief was lost in the increased expenditures to operate city, county, and state orphanages, poorhouses, and asylums.

So what connections can be drawn between the BTFRA and the move to privatize all benevolence in Brooklyn? Certainly, the personnel and organizations involved in the two movements were nearly identical. Ripley Ropes, the leader of the movement to abolish outdoor relief, was president of the Brooklyn AICP, the group that provided the professional framework for the Brooklyn Theatre Fire Relief Association and took over the responsibilities of outdoor relief. Ropes also helped establish the BTFRA and served on its executive committee. Reverend Alfred Putnam, the key figure behind the BTFRA, aided Ropes in his investigation of the Charity Commissioners. Mayor Frederick Schroeder, the former president of the BTFRA, strongly supported Ropes’s efforts and later, as a state senator, led the efforts to indict the Charity Commissioners on charges of malfeasance. These men and the host of supporters they brought together all were staunch Republicans and members of the elite establishment in Brooklyn.

However, the BTFRA cannot be described as the sole inspiration behind the private charity movement, as that crusade predated the theater fire. Instead, the Brooklyn Theatre Fire Relief Association provided these elites with a model for and experience in private charity that they could transpose upon the entire city. Proving that the private model as represented by the BTFRA had succeeded in providing for the families of fire victims, these same elites sought to expand the system to cover all 50,000 people on relief in Brooklyn.

Henry Ward Beecher, the favored religious leader of many of these elites, made the connection explicit. Beecher had been a tireless fundraiser for the BTFRA, but in November of 1878 he transferred his efforts to making appeals for Ropes’s AICP. “Within the past two years, a change has been made in the system of relieving the worthy poor, and the change seems to be a good one,” Beecher said, calling the AICP “a very wholesome and desirable substitute for the old system.” To those who questioned private charity, Beecher pointed to “the money subscribed by a grieving city for the relief of sufferers by the Brooklyn Theatre fire disbursed by philanthropy … in a most satisfactory way.” For Beecher, speaking for his well-to-do parishioners, the evidence of the BTFRA’s success demonstrated the efficiency of private charity.

Behind the congratulatory plaudits and political power these elites gained from their work privatizing charity in Brooklyn in these years, there was a recognition, at least by some, that the power of private charity was limited. Dr. Thomas Norris, one of the Commissioners of Charities who opposed the abolition of outdoor relief, observed the shortcomings of private philanthropy in his year-end report for the Board of Supervisors. Private charity was appropriate on a small scale such as the theater fire, Norris wrote, but in cities the size of Brooklyn, “very many more cases require help than private benevolence can reach.”

Yet Norris, discredited and dispirited, was a voice in the wilderness. He was indicted as a result of Ropes’s and theEagle‘s investigations, and though he was acquitted, his career was over. The “success” of the Brooklyn experiment encouraged other cities to follow their model. By 1900, outdoor relief was abolished in nearly every major urban area in the United States. The success of men like Seth Low, Alfred Putnam, Ripley Ropes, Frederick Schroeder, and their counterparts across the country did not rest in insulating the poor from pauperism, removing politics from charity, or even saving the taxpayers money, as they claimed. Rather, their triumph came from seizing control over the mechanism of urban charity, giving urban elites a valuable method of social control that reflected earlier private models of urban charity. Ropes, Low, and other upper-class political figures self-consciously returned to this form as a way to undercut the power of political bosses like Hugh McLaughlin. McLaughlin derived much of his power from his ability to provide aid to the city’s working class. By arranging charity along private, “business-like” lines, Low and Ropes hoped to shake the machine’s hold over aid recipients and further their own political ambitions.

The abolition of outdoor relief in Brooklyn was not the only lasting legacy of the Brooklyn Theatre Fire, however. Indeed, the fire helped transform the very structure of the American theater itself. While the BTFRA was investigating aid-seekers for their economic and moral conditions, another sort of investigation was ongoing. City authorities sought to identify the causes of the fire and establish blame, if necessary. On December 7, Coroner Henry Simms impaneled a jury to hear testimony and determine the cause of the fire. Ripley Ropes was named foreman of the jury, and he was joined by many of Brooklyn’s most prominent men, including streetcar magnate William “Deacon” Richardson and warehouse owner Samuel McLean. Simultaneously, Patrick Keady, the city’s fire marshal and member of the Democratic machine, began his own investigation (fig. 8).

Keady finished his investigation first, releasing his findings on December 14, just two weeks after the blaze. His scathing conclusions laid blame on the theater’s owners, Sheridan Shook and A.M. Palmer. He noted that the theater had little means to extinguish fires—Palmer and Shook had disconnected the hose attached to the theater’s fire hydrant—nor were the stagehands prepared to deal with emergencies. Finally, though Keady acknowledged the ease with which most patrons fled the theater, he concluded that the single biggest reason for the death toll was the narrowness of the stairs down from the gallery to the exits. While in normal circumstances the stairs were adequate, Keady noted, “they could not afford safety with a panic and fire, such as occurred in the Brooklyn Theatre, raging together.”

The coroner’s jury, which released its report at the end of January, came to similar conclusions. Shook and Palmer were “guilty of a culpable neglect” of safety measures in the theater, and the jury recommended that they face criminal charges (which they ultimately avoided). Beyond that, however, the coroner’s jury also set forth a series of remarkable recommendations for all theaters in Brooklyn that sought to prevent a similar disaster from happening again. The New York Mirror led the way, declaring the coroner’s jury’s proposals—which included enclosing the gaslights in iron fenders, building a brick wall to separate the stage from the rest of the auditorium, and developing safer materials for use in scenery—as “sound and sensible” principles for remaking America’s theaters. And indeed, some theaters took these precautions to heart. Under the recommendation of architects called to consult on safety measures, the owners of the Coates Opera House in Kansas City (originally erected in 1870) added a brick wall to separate the stage from the rest of the auditorium as a means of fire containment, while several theaters in New York City closed in order to expand the exits to accommodate more patrons.

Both the Brooklyn and New York fire departments briefly experimented with stationing groups of firefighters in theaters for every theatrical production in their respective cities, but this proved to be too expensive and too difficult to manage, particularly in New York, and was discontinued after a few months. One enterprising theater owner in New York coated his sets with an anti-incendiary powder that had the unfortunate side-effect of leaving his actors unable to perform due to lung irritation after they inhaled the powder. The recommendations of the Brooklyn coroner’s jury were too expensive or impractical for most established theaters to adopt, and without a set of guidelines, things quickly returned to normal. Reviewing the measures taken by New York theaters in 1881, theInsurance Times declared “there is not a safe [theater] in New York,” and recommended adjusting insurance premiums upwards.

Theater owners and patrons alike were jolted out of their complacency soon, however, after a devastating fire tore through Vienna’s Ringtheater during a performance of Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffman on December 8, 1881—almost five years to the day after the Brooklyn Theatre disaster. The circumstances of the Ringtheater fire were remarkably similar, although the death tolls were markedly different. While the Brooklyn Theatre Fire claimed “only” 283 victims, the Ringtheater disaster took the lives of anywhere between 620 and 850 people. It remains the deadliest theater fire in world history.

Brooklynites, and members of the original coroner’s jury in particular, were quick to point out the connection between the two disasters. Ripley Ropes told the Brooklyn Times that, “the similarities between the two tragedies are such that they might as well be duplicates.” Ropes, at the time preparing to become the city’s commissioner of public works under mayor-elect Seth Low, joined with Brooklyn Fire Chief Thomas Nevins to revive the coroner’s jury’s proposals for making Brooklyn theaters safer, updating them slightly. The proposals still contained demands to widen and increase the number of exits and separate the stage from the rest of the theater, but they also included provisions for having a telegraphic connection between every theater in the city and the fire department. Nevins presented these proposals to the Brooklyn Common Council, noting that only the Brooklyn Opera House and the new Brooklyn Theatre (built on the same site as the old theater) had any sort of fire precautions at all. The city’s Progressive reformers, epitomized by the energetic Low, embraced these ideas; after taking office, Low insisted that Brooklyn Fire Department investigate every theater in the city to ensure they met Nevins’s standards.The Eagle summed up the spirit of the movement by insisting that “if the proprietors of theaters cannot be induced to voluntarily adopt these or kindred experiments, it will be in order to consider the propriety of making them compulsory.”

The call for reform soon spread across the East River. The Mirror was New York’s premier literary and artistic newspaper, and was one of the loudest voices for reform in the wake of the Brooklyn Theatre Fire. The Ringtheater disaster reawakened them to the need for regulation and reform of the physical space of the New York theater. “The carelessness that caused the Brooklyn fire is still apparent in even the finest theaters of New York,” the Mirror charged, asking “will it take yet another conflagration to compel managers to adopt measures to protect the public?” The Mirror‘s advocacy pushed the New York Fire Department to conduct a thorough investigation into the conditions of the city’s theaters. Their findings—that many theaters did not have an appropriate number of exits, nor did they have proper facilities for those in balcony seats to escape—proved The Mirror‘s point.

The Mirror, the Eagle, and other reformers faced entrenched opposition from theater managers and proprietors, who argued that the reforms that Ropes, Nevins, and others suggested were far too expensive. Colonel William Sinn of the Brooklyn Park Theater complained that if he undertook all the reforms that Nevins suggested, he “would be obliged to raise ticket prices to a level well above the reach of a working man.” This appeal to the working classes, coupled with many theater owners’ connections to both New York and Brooklyn’s Democratic machines, made the theaters a formidable opponent. Yet the public, shocked by the prospect of a New York catastrophe on the scale of Vienna’s Ringtheater, largely sided with the reformers. Nor was the theater owners’ cause helped by a series of theater fires across the country (the Mirror estimated that 13 theaters burned down each year between 1871 and 1881). Indeed, as historian Benjamin McArthur notes, “anxiety about theater fires [in New York] even influenced drama, as nervous audiences lost their taste for realistic fire scenes.” The public, the press, and municipal reformers all demanded action.

In 1882 and 1883, the state legislature and the Common Councils of Brooklyn and New York took action. Though theater owners were able to dilute the legislation, new regulations by the state forced all theaters in New York to provide at least four separate exit ways and to widen all existing exits. New York City went further, prohibiting theaters from building sets on theater premises, and limiting the amount of sets and props a theater could keep in storage. Brooklyn’s Common Council, then under the control of a reform element, went further, requiring the placement of a Theatrical Detail Officer at every theater to inspect the theater’s fire-prevention facilities and the exits. Coming as it did just as theaters in New York were “creating” Broadway as we know it today, the improved regulations played a very important role in drawing families back to New York City theaters, and perhaps saved the theater’s reputation at a critical time.

Of course, there would be other fires. The most notable, the Iroquois Theater Fire in Chicago in 1903, was the single most catastrophic loss of life in U.S. theater history, as 605 people lost their lives in the fire. That fire finally spurred New York City to adopt many of the regulations that Ropes and Nevins had first suggested in the 1880s. By 1910, all city theaters had to be equipped with a brick wall separating the stage from the auditorium, sprinkler systems, and extra, clearly marked emergency fire exits. These changes have largely created the physical space of the theater as we know it today, and made it a much safer space than it was at the time of the Brooklyn Theatre Fire.

The fire remains a crucial moment in Brooklyn’s history. For years afterward, Brooklyn’s newspapers would compare every great fire to that of the old Brooklyn Theatre. Folk songs were composed and sung about the fire, and there were even stage plays offering fictional recreations of the story in the years to come. Even Kate Claxton, who survived the fire and indeed perhaps achieved national fame for her part in it, remained tied to the fire in the public’s imagination. For years after the fire, Claxton was seen as a theatrical “Jonah,” as theater fires—or at the very least panic over false cries of “fire”—seemed to follow her as she toured the nation in the role she made famous in The Two Orphans. In 1892, the Louisville Courier published a profile of Claxton, noting that “for over fifteen years, she has been pursued by a particular form of ill luck … several fires and a dozen or so panics.” Claxton herself believed (or so she said) that she had a reputation “as a fire fiend,” “pursued by an evil genius.” Claxton retired from performing in 1911, living comfortably on earnings from performances and filmed versions of The Two Orphans (to which she owned the performance rights). Yet, her reputation as “Kate Claxton of the Big Brooklyn Fire” followed her until her death in 1924. Perhaps it is fitting, then, that Claxton is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, very near to the monument erected in honor of many of the fire’s victims.

Further Reading

Those interested in the state of American theater in the decades after the Civil War should see Benjamin McArthur, Actors and American Culture, 1880-1920 (Iowa City, 2000) and The Man Who Was Rip Van Winkle: Joseph Jefferson and Nineteenth-Century American Theater (New Haven, 2007); Gillian Rodger, Champagne Charlie and Pretty Jemima: Variety Theater in the Nineteenth Century (Urbana, 2010); and, most recently, Amy Hughes, Spectacles of Reform: Theaters and Activism in Nineteenth-Century America (Ann Arbor, 2012).

The literature on urban poor relief and welfare is voluminous, but a good start can be made with Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A History of Social Welfare in America, tenth anniversary ed. (New York, 1996); Walter I. Trattner, From Poor Law to Welfare State: A History of Social Welfare in America, sixth ed. (New York, 1998); and June Axinn and Mark Stern, Social Welfare: A History of the American Response to Need, seventh ed. (Columbus, 2007)

No good full-length literature on the Brooklyn Theatre Fire itself exists, though readers may enjoy Brooklyn’s Horror: A Thrilling Personal Experience (Philadelphia, 1877), a cheap dime novel supposedly written by one of the theater fire’s survivors. Though the book is of dubious veracity, it is extremely entertaining. The book is available to view online at Google Books.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.4 (Summer, 2013).

Joshua Britton recently received his PhD in American history from Lehigh University. He is currently revising his dissertation entitled “Building a ‘City of Churches and Homes’: Elites, Space and Power in Nineteenth-Century Brooklyn” for publication