Types of Mankind: Visualizing Kinship in Afro-Native America

This is a tale about my return to the vault. It’s about those moments when something in the archive catches you completely off-guard—and nearly knocks you off your feet. It’s a story about how a scholar of literature was taught to sharpen her vision and see beyond the printed page.

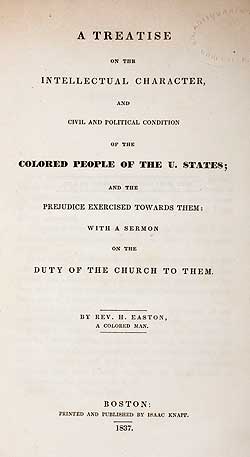

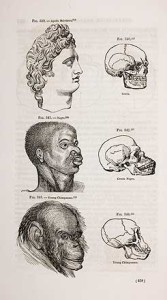

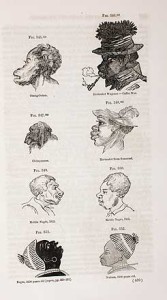

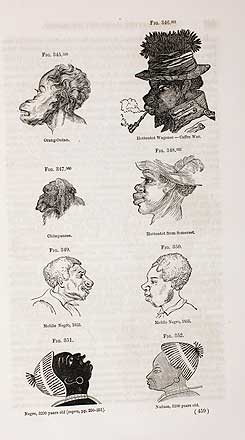

I originally intended to write about the dynamic and neglected history of African American engagements with natural science in early black print culture (I still intend to do this, but in a different and perhaps unconventional way). More specifically, I was interested in discussing my experiences at the American Antiquarian Society with a set of little-known ethnological tracts written by African Americans in the 1830s and 1840s, including James W.C. Pennington’s 1841 Text Book of the Origin and History of the Colored People, Hosea Easton’s 1837 Treatise on the Intellectual Character, and Civil and Political Condition of the Colored People of the U. States, and what is generally regarded as the first ethnology written by an African American, Robert Benjamin Lewis’s 1836 Light and Truth, From Ancient and Sacred History. Pennington, Easton, and Lewis all wrote ethnologies that challenged the ascendency of the so-called American school of ethnology in the 1830s. Its practitioners—most famously Samuel George Morton, Louis Agassiz, George Gliddon, and Josiah Nott—used the tools of comparative anatomy to attempt to prove the innate mental and physical superiority of the Caucasian race. These comparative studies of human anatomy and physiognomy sought to demonstrate the biological and evolutionary degeneracy of African and African-descended peoples. They were also invested in upholding the thesis of polygenesis: that non-white races were not only biologically inferior to the Caucasian race, they also originated in separate creation events by God (they were both inferior and separate “types” of people). In response, black writers and intellectuals waged a war on the American school of ethnology through the creation of a counter-archive of ethnological writing, which told a different story about the origin and descent of the races. Black ethnologies often affirmed the monogenetic hypothesis—the idea that all races were descended from a single stock, rather than through individual creation acts by God, but they also moved beyond monogenesis to make even bolder claims about the descent of man: all races were indeed “of one blood,” they argued, but the white race was actually descended from the black race since the Ethiopians were the first men created by God. These ethnologies boldly proclaimed that the Garden of Eden was in Ethiopia, and hence, Adam and Eve were black. In addition to placing themselves at the center of Biblical history, black ethnologies insisted on the deep influences of Ethiopia on the development of so-called Western civilization in ancient Egypt and across the Mediterranean world: they often, for example, included lengthy lists of Greek and Roman historians, poets, statesmen and philosophers who were of African descent, including Plato, Ptolemy, Alexander the Great, Cicero, Nero, Julius Caesar, and Augustine. In short, these ethnologies offered a rich and expansive view of a glorious black past: African American ethnology challenged the American school of ethnology’s view of the black race as an evolutionarily degenerate group, but it also refused attempts to disinherit African Americans from their illustrious roots and place in history, secular and sacred.

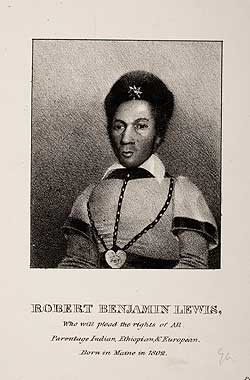

At least those were my plans. And then I stumbled upon an image, an image that completely transformed the direction of my research by throwing into question many of the major assumptions I carried into my study of African American ethnology. I had returned to the AAS for a two-day trip in which I planned to check a few facts and confirm a couple of citations for a project I had already spent a month researching at the library. That morning, I noticed a citation in the catalog on Robert Benjamin Lewis that I hadn’t seen before. I thought I should give it a glance, but didn’t expect it to be relevant to my project. I put in the request so quickly that I didn’t realize I had requested a graphic item. I expected to receive a text. Instead, I opened the folder to a beautiful, dazzling lithograph of Robert Benjamin Lewis himself (fig. 1). I stepped back a few steps and covered my mouth. It was an incredible discovery: in all of my work on Lewis and his ethnology Light and Truth I had never come across an image of him. By pouring over pages and pages of text—of newspapers, books, pamphlets, and other print sources—I expected to learn more about Lewis’s life and his writings, but I never expected to encounter his actual image.

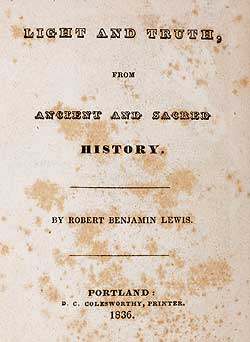

Born in 1802, Robert Benjamin Lewis was a freeman of African and Native American descent. He was born in Maine, where he also lived, worked, and raised a family. Some sources suggest that he passed away in Bath, Maine, in the late 1850s, while others claim he took sick and died in Haiti while scouting out a place to emigrate with his family. In her history of black thought on the white race in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, The White Image in the Black Mind (2000), Mia Bay refers to Lewis as a “jack-of-all-trades” who “made his living painting, papering, and whitewashing houses, cleaning carpets, crafting baskets, caning chairs, and fixing parasols and umbrellas” (44). Little else is known about his life except for the publication of his ethnological tract in the mid-1830s. Before it was published as a bound volume, Lewis circulated and sold pamphlets of his Light and Truth during a lecturing tour of New England. It was first published as a book (fig. 2) in 1836 by the Portland, Maine, printer and poet Daniel Clement Colesworthy. That same year, Lewis set out on another book tour of New England to sell and promote his newly published book. The many re-printings of Light and Truth in the 1840s and 1850s suggest that Lewis’s ethnology circulated widely in the region: in 1843, a newly revised and expanded edition was published as a four-volume serial in Augusta, Maine, and in 1844, a self-named “committee of colored gentlemen” in Boston published the expanded serial edition as one large volume. The 1844 edition (fig. 3) was printed by the shoemaker turned radical printer, lecturer, and activist, Benjamin F. Roberts, who also sat on the aforementioned committee. In addition to publishing Lewis’s Light and Truth, Roberts had other connections to the foundations of black ethnology: his nephew was none other than Hosea Easton, who published his own ethnology in Boston in 1837 (fig. 4). The 1844 edition of Light and Truth was reprinted by Roberts in 1849 and again in 1851. Lewis’s regular book tours and lectures must have expanded his readership and audience even further. Bay suggests that Lewis’s annual book tours may have made Light and Truth the most widely circulated black ethnology in the nineteenth century.