The Unbearable Taste: Early African American Foodways

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.From Langston Hughes, “I, Too, Sing America”

Setting the Table

As an interpreter, researcher and educator in the subject area of enslaved people’s lives and foodways, I am often asked, “where did you go to learn all of this?” The sincerity of the question enhances the awkwardness and anguish of making a humorous retort. My reply generally goes: “Well, I read. I cook on the hearth as much as possible. I listen to the elders of my past and those who are left, and I make mistakes and learn not to repeat them. I lose my eyebrows and arm hair to the fire, and often burn my hands and spill things. Sorry, there are no B.A., M.A. or Ph.D programs in how to cook like an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century slave or how to work in a cotton, tobacco, corn or rice field.” There is nothing sexy about what I do. And what little feeling of “comfort” people get from the smells, stories and samples I have to offer is quickly turned bittersweet by the discomfort of the real meat of the meal—slavery.

We don’t shy away from slavery as much as we once did. It always seems to raise eyebrows and get the discursive blood flowing. Most of this kinetic response comes from thinking about slavery as a challenge to democracy. The same could be said for the mythos surrounding the Underground Railroad, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights movement, in which what we debate is not what made this debate necessary in the first place—slavery—but rather how the debate was resolved in terms of protests, movements, politics, wars, great men and women. I am an iconoclast. I’m really not turned on by this lofty democracy talk. It doesn’t tell me how I got here, how we got here. In some ways it makes me angrier because slavery rolled into quasi-freedom in slow motion, while wars of independence and the birth of the personal computer seemed to revolutionize American life in minutes. I cannot understand my history looking through that lens. Slavery was not a complication; it was a civilization.

My hero is not the freedom seeker as much as the one who endured the institution out of sheer survival and the promise of better times and freedom as an inheritance for posterity. My great questions do not revolve around the southern Founding Fathers and their issues with “the Peculiar Institution.” I care about the enslaved world they tried to shield themselves from with fences and hedgerows, columns and dumbwaiters even while they lived in its midst. The smell, sound, feeling, and unbearable taste of being black and enslaved is where I find our common genesis. Slavery was central to the American economy, the birth pangs of black America, and served as the underpinning narrative of all other definitions of ethnicity in America to come; the chains are still on us.

There is no better way to encourage people to understand and empathize with the enslaved than through food. While these “notes from the field,” are intended to create a picture of my process and findings, I should state outright that by recreating and preserving these traditions, my ultimate mission is to give humanity and dignity to my ancestors. Invariably, my audiences will often participate in some part of the food preparation. Children will understand concretely what being enslaved was like. Elders will testify to witnessing the vestiges of the nineteenth century in the dimness of their childhood, and people of various colors and cultures will find themselves in my ingredients, methods, and narratives. Whatever poetry, truth, or wisdom people find in what I do or teach, they themselves bring to an already prepared table. What follows here is a sense of what they find at the feast.

Early African American foodways—toward a definition

Is slave food soul food? Is it born in Africa and transported to America or is it inspired by Africa but essentially an American creation? Does it center itself in key staples or is it the improvised brainchild of iron chefs in iron chains? Alternatively, aren’t early African American foodways really just the black side of a generic lower-class, early American palette?

Definitions are notorious for being the simplest way to be complex. It’s easier to say what the label “early African American food tradition” does not connote than what it does. It was not soul food, even though it’s clear there would have been no soul food without enslaved people’s food. Soul food is the moniker that the great-great grandchildren of enslaved people gave to the accumulated culinary knowledge and flavors that they felt helped to define them as an ethnic group. However, soul food has a spice that enslaved food did not. The average enslaved person would only intermittently enjoyed elements of the classic “Sunday dinner” of soul tradition. Poor whites in early America shared some of the staple foods that enslaved people consumed, but they were not accountable to a “higher authority,” like a master or an overseer, when they sat down for their meals; and poor whites, if they acquired the financial means, could purchase or grow or raise whatever they wanted. Access to ingredients and luxuries and accountability to white figures of authority were navigated by the enslaved through patterns of resistance and both individual and communal empowerment. Not to mention the fact that we have racialized certain foods and cooking methods over the past two and half centuries for definite reasons—they were associated with Africans, African Americans, and enslaved people. To ignore this is to disregard historic perceptions of ethnicity as well as the ways that we simultaneously create parallel cultures and maintain distinctions between them. Neither modern soul food nor the food of lower-class whites contemporary with American slavery serve as useful models for how enslaved people ate.

What we can say about the ultimate origins of early African American foodways is that it would have not taken the same shape had it not been born in a complex nexus known as the “African Atlantic.” The foodways of the West and the Americas were not first introduced to enslaved Africans in America, they were introduced in Africa, sometimes long before contact with Europeans. This pattern of exchange built on connections with the Islamic world and Southeast Asia; it drew African plants and foods north and east even as ingredients and dishes from these regions came into the African world. Commensurate with the creation of new Creole languages, spiritualities, and aesthetics in the Atlantic world was a flowing food tradition that drew on West and Central Africa for its deep structure, values, and “grammar,” as Charles Joyner once put it. This tradition then found in European (and by extension, Native American) traditions, the parallels, luxuries, limitations and possibilities that created an edible jazz. In key regions—Senegambia, the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), southeastern Nigeria and west-central Africa, the culinary negotiations were immediate and palpable. American crops parallel to African cultigens would come to flourish—think maize and cassava, tomatoes, peanuts and curcubits. Where classic African traditions, Creole innovations, and caste control met, there the foodways of early African America were born.

Early African American foodways were also the product of the interplay between ethnic groups from West and Central Africa and new “nations” that emerged out of the catalyst of the Middle Passage. People drawn from a 3,500-mile stretch of coast who had no contact with each other before the slave trade now found themselves having to work out a common Afri-Creole food tradition parallel with a common Afri-Creole tongue and culture. Wolof met Igbo, Mende met Mbundu, Akan met Fang. There was also some level of exchange and movement between enslaved communities in mainland North America and those from the Afro-Caribbean and Latin America. The story is made yet more complex by the fact that whomever enslaved and liberated Africans lived among—be they Dutch, Swedish, Scots Irish, German, Sephardic Jewish, Cherokee, Creek, French or Spanish—would either enrich or limit the culinary realities of their exile in America. No enslaved cultures in the history of the world have had such an enormous influence on the national cuisines of its sojourn than the peoples of the African Atlantic and the African Americas.

Transitions of taste

It has occurred to me that if we were to transport enslaved African Americans through time to the present, they would be amused and amazed with the current trends in American food. Local, seasonal eating? Sure! More than anyone else, enslaved people had little choice but to rely on the immediate environment for their needs since they were literally bound to the land. Eating offal, wild plants and game as something chic? Perhaps not chic, but necessary and favorable? Absolutely. Comfort food prepared and served in unpretentious ways, eaten as a “mess”? Affirmative. Underground eating, food prepared and served guerrilla style apart from the prying eyes of authorities and judgmental eaters? Again, a winner. The conventions of enslaved people’s foodways from the colonial and antebellum periods are remarkably consistent with contemporary passions about the possibilities and power of food as a communal experience.

Enslaved Africans and their descendants clung to hot and spicy foods. They maintained their cravings for salt, grassy leafy greens and herbal tonics. They liked their soups and stews with gummy okra and other mucilaginous textures; they favored one-pot meals where flavors melded and rice cooked so that every grain was single and distinct. They punctuated heavy starchy fillers with the unctuous flavor of heavy oil and crispy outside skins of fried foods. They satisfied their desire for what foodies now call umami (meaning mouthfeel) with parboiled roasted meat, boiled peanuts, and the slightly aged and fermented taste of preserved fish and meat that lent savor to cowpeas.

But there was no single enslaved food culture.

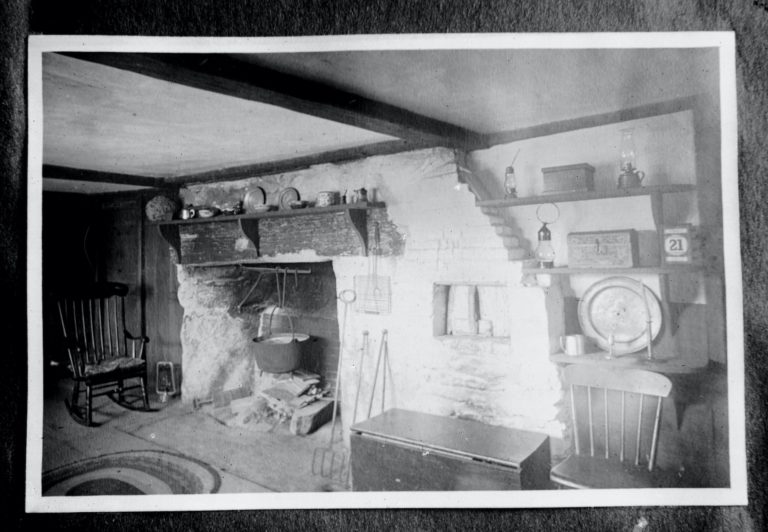

One fundamental shift in what this cuisine looked and tasted like probably occurred about the same time that the majority of enslaved blacks were American born—a shift that occurred between1740 and 1760. By the end of this period, the trade in enslaved peoples began to slow and was ended in the North and Chesapeake by the 1780s. In the Lower Mississippi, Gulf Coast and Lowcountry, successive waves of late importations would continue into the nineteenth century, well past the congressional close of the slave trade in 1808. The result was that the cuisine of the Lower South reflected ongoing influxes from Africa long into the nineteenth century. In the Chesapeake, influential to the Upper South and parts of the cotton belt, the cultural impact of earlier demographic patterns was key to the uniquely African American approach to Southern food. The foods, cooking methods, and manners of eating that appealed to, say, a man arriving from what is now southeastern Nigeria in the 1720s might not be so appealing to his great-granddaughter born in southeastern Virginia in the 1770s. Technology would have accounted for some of the differences in taste between this man and his great-granddaughter. He would have grown up in a household where a kitchen hearth was an outdoor or separate building with a fire pit that held three supporting stones on which a slim variety of clay or iron trade pots could be placed. Wooden spoons, large knives, mortars and pestles, brush whisks, baskets, grinding stones and gourds used as bowls were the primary culinary implements. Contrast this with the brick hearth, metal pots and pans, and multiple utensils that his great-granddaughter might have used as a cook in at the home of a prominent Virginia master. In her world, food was to be served in courses, and made into separate dishes rather than a single pot entree. And the food she prepared would have included baked goods, a novelty to her great grandfather, whose traditions did not include either wheat flour or long baking.

Africans living in the Americas, like their European counterparts, developed a sweet tooth. European and Islamic tastes for honey-flavored desserts lost ground to king sugarcane. The traditional African palette favored bitter, spicy and oily dishes over sweet ones. Raw honey, sugarcane or sorghum cane (native to Africa and brought to the South in the mid-nineteenth century) and fresh fruits were valued but not essential snacks. In the Americas, however, Africans would not only cut cane, but would come to develop new ways of their own to produce confectionary. Sucrose was one of the few comforts known to bonds people. Great-grandfather may have looked askew at anything but fresh fruit and honey; but his great-granddaughter would already be fond of jumbles, biscuits, cakes, sweet bread, jams and other delights including a newly introduced preparation from grain—macaroni.

Both great-grandfather and great-granddaughter would have based their “vegivore” diet on a starchy preparation made from grains and tubers enhanced with leafy greens and bits of meat or fish and nuts or legumes as protein. While great-grandfather’s diet was based on yams, legumes, some millet and sorghum and leafy greens from tropical crops, great-granddaughter’s diet was based on corn first and foremost, supplemented with legumes, sweet potatoes and leafy greens from temperate brassicas. Both diets would have incorporated African ingredients or New World substitutions. Okra, Bambara groundnuts, sesame, cowpeas, sorghum, watermelons and muskmelons, hot peppers, and peanuts all provided a taste of an African home. Sweet potatoes, temperate and tropical pumpkins, Eurasian brassicas (like cabbages, kale, collards) and a variety of indigenous North American fruits—berries, persimmons and the like—were substitutions for West and Central African foods. At the same time, foods consumed by enslaved blacks in the Americas found their way to Africa. The corn that would have been so important to great-granddaughter was consumed on both sides of the Atlantic. Like other grains and tubers, it was mushed, popped, roasted, fried, cooked into flat cakes, and made into loaves. The sole difference between its African and American preparation was that nixtimalization (treating corn with lye or lime to loosen the hull as in hominy) was not utilized in West and Central Africa although the process was endemic to the southeastern coast of North America. The result was that corn remained a poor addition to the diet in Africa, but served as a fairly nutritious food in America.

And meat? Great-grandfather would have enjoyed heads, feet, innards, tongues and eyes of domesticated livestock. Each part would have had its own spiritual and culinary meanings and savor. His great-granddaughter would relish what protein she could get but was tempted by the cuts her owner preferred. Long after slavery, her descendants would look on the cast-off parts with disgust and associate them with powerlessness rather than their equally important roots in West and Central Africa.

While Europeans (and Native Americans, for that matter) influenced the foodways of the enslaved community, enslaved women and men also influenced the food traditions of their neighbors and owners. Native Americans in the southeast began growing watermelons, sweet potatoes (read “yams”) and cowpeas. Europeans could not live without pepper vinegar and other condiments influenced by fiery African tastes. Native persimmons replaced the fruit of the ebony tree and pawpaws were substituted for bananas; cutting grass rat stewed with yam became possum roasted with sweet potatoes; violets became “wild okra.” Early receipt books give a hint of the transformation from European to Southern. We can see the shift with every recipe for fried chicken, turnip tops cooked “Virginia style,” chickens stewed with sweet potatoes, gumbo, hoppin’ John or cowpeas cooked with rice, black eyed pea cakes, barbecue (a term with possible roots in the Hausa word “babbake/babbaku,” “to grill or toast”), sweet potatoes cooked in syrup, okra soup, and treats made from plants with African names like “fevi/ochra/gumbo” (okra) “benne” (sesame), “goober” (originally referring to the Bambara groundnut, later the peanut), “pindar” (peanut), “cala” (a fried rice ball), and fried plantains, the bananas cooked in New Orleans. We should not confuse written “receipts” with real dishes. Not all dishes had names, and the necessity of improvisation meant that a mess of wild greens eaten with a hoecake has only as much meaning as we assign them. But to West and Central Africans and their descendants, dinner was always a starchy or leafy dish eaten with a soup or stew or, much more rarely, a roasted or fried protein.

Research, interpretation, presentation and preservation

There is a lonely sense of merit attempting to embrace and interpret the enslaved cooks of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The audiences at my museum demonstrations and programs admire what I do, but few patrons express interest in joining in the reenactment. There are no legions lining up to participate as there are with Civil and Revolutionary War enthusiasts. Accuracy is hard to assess. And anyway, “cooking as the slaves did” should really be me serving a visitor or student a bowl of mush or rice or a corncake with no frills except perhaps some salted meat or fish, and water, for several meals a day. That might be the most jarring and authentic way to transfer the message: Enslaved foods were supposed to be filling and blandly satisfactory, not tasty and comforting.

The prospect I lay out for the visitor is quaint but unbearably tedious. I must rise before sunrise, and using the leftover coals, re-ignite the fire, often building a wooden tower from which large shovelfuls of heat-giving charcoal will rise. It’s important to know what type of wood to use, knowing each has its own burning qualities, taste, and levels of neutrality and savor. The menu is determined by which animal is in its prime and which garden truck is in season. To feed both Big House and slave cabin, I have to answer a flurry of questions:

What species of wild flora and fauna were a part of the diet and what is their present status as food—rare/endangered/threatened/common? (As much as I am responsible to accurately re-create the past, I have a greater responsibility to the future.) What heritage breeds and heirloom vegetables and grains approximate the tastes known to the people of the past? When is poke safe to eat? What are the breeding habits of possums? What is the proper way to eat a biscuit? Which hand do I use? What is the color of a ripe persimmon? The folk knowledge that went into cooking for kitchens high and low is immense. One has to know blanc mange as well as ashcake. Is jambalaya au congri from New Orleans the same thing as hoppin’ john in Charleston?

The receipt books of the past are my tour guides; they get a vote but not a veto. One has to allow for “work presence,” as Karen Hess defined it—the moment a cook deviates from the formula, which in itself is only a distillation on paper. I allow my informants—the formerly enslaved and their observers—a say. I also focus on locally available foodstuffs. I cannot assume that because a food is available in one place it is available in another, or that what is common today was common in the past. I grow the herbs and heirlooms I need for the pot months in advance, source protein from farmers and hunters and fishermen, order for rare and costly grains, and limit myself to the seasons’ produce. It is difficult but necessary work.

I also rely on written sources ranging from Hannah Glasse and Adam and Eve’s Cookbook through Mary Randolph, Lettice Bryan, Sarah Rutledge, Elizabeth Lea, Mrs. Hill, Lafacdio Hearn, B.C. Howard and the Times-Picayune to Robert Roberts, and Mrs. Abby Fisher. Historical receipts and cookbooks must be mastered even if they don’t have absolute power over me as an interpreter. One has to know and how to subtract and add ingredients according to the needs and restrictions of the enslaved community. In a sense, my working goal is to master two or perhaps three cuisines—the meals of the British-French-American classics of the Big House, soup to nuts, patty shells to snow eggs; the foodways of the enslaved community in times of want and of plenty; and the outskirt, antique parent traditions of West and Central Africa, Brazil, and the Afro-Caribbean and Latin America. These traditions serve to inform and verify the work of re-creating and restoring.

Some might question my expansive/inclusive approach to documentation. The only universally acceptable form of evidence seems to be limited to observations made by white men living 200 years ago. I reject this as not only culturally biased but short-sighted. Evidence for the foodways of the enslaved can be gleaned from the remarks of slave traders, slave owners, and plantation visitors and some of this evidence is amazingly specific. However, these observations have to be weighed against the cultural backgrounds of an enslaved community, the ethnicities they encountered, the available food in any given region, the accounts of enslaved people themselves, historic receipts, and not least the oral tradition, culinary traditions, and memories that have filtered down into the present. Culture bearers are important counter voices to academic pronouncements. To suggest that my 92-year-old grandfather has nothing valid to add to the discussion, despite his having lived in the rural South in an era not much different from the antebellum period or having been in the presence of his enslaved grandparents; or that the testimony of a West African immigrant or the ethnographic writings of the early colonial period are moot merely because they were not recorded during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, is ludicrous and arrogant. Checks and balances on the sources and accuracy of data are fairly intuitive. If nothing else I work with the dictum, “if you can’t prove or prove it reasonable, don’t say it or cook it.”

There is of course a body of knowledge that only experience can help accrue. It is impossible to understand what it meant to be a cook if you have not experienced the fear of moccasins in a Carolina rice paddy or known the blindness that the sun casts on cotton on a hot early autumn day. Tobacco stains the hand and tasseling corn numbs them. The lower back and feet ache from hours on brick kitchen floors. You learn the wisdom of the recipes for salves and cures listed in the same receipt books that provide inspiration for menus. Your arms will teach you about the heft needed to carry 40- and 60-pound pots and the stamina it takes to cook a large meal by the standard dinner hour of two or three p.m.

These experiences are still not as instructive as the ones that time, place and fortune excuse me from. What if I was forced into the field for half a day to get the harvest in and made to leave the relative safety and privacy of the kitchen? Conversely, what if I had to feel the daily loneliness of the kitchen, being separated from much of the rest of the enslaved community? What if I was whipped for tasting too much or not tasting enough and sending out something burned? What if my accidents and tardiness were not forgiven? What if I had to wear the horse’s bit to keep me from eating though I was malnourished?

Free to fail in a way my ancestors never were, my work is spent scouring letters from slave traders, WPA slave narratives, and emancipatory narratives and recording my observations about the smell of game musk, gardening by pine-knot and moonlight, and trials and error with Spanish moss as support for baking dishes. I am now a veteran hog-butcherer, from dividing up the carcass to salting the meat down to each pore. I know the forearms it takes to pound corn and rice and the caution one should exercise when attempting to catch bullheads, crawfish or snappers. I’m working on having the “light touch” in baking, on expertly executing the multi-hour antebellum barbecue, and designing the perfect roux. Frequently I find myself on sourcing safaris where I find Senegalese cowpeas and bitter leaf, dried okra and calabaza and spiny gherkins and hunt down Sieva beans and sesame seeds to plant. Though I am not bound by the colonial and antebellum calendars, I trace time in terms of tobacco and cotton seasons, acknowledging the 101 labors needed to produce food on the plantations of yore—from orchard work to slaughtering to salting fish to shifting the gardens and truck patches from spring to snow, and treating the treats of historic cookery with the respect of a starving man.

The other part of the work is preserving it for the future. Putting measurements to orally transmitted compositions for recipes is not enough. Some foods are dying out not because they are physically endangered but because they are culturally endangered. Reenactment is also reintroduction. You have to eat it to save it. You have to ensure the tastes will endure that make the history relevant and alive for the enthusiastic learner. African Americans are still not well represented in the current drive to save our national and regional heritage foods. Yet these are the same foods that reverberate with deep and complex histories and that connect us to global legacies. My mission is to use this platform to reconnect my people with the culinary heritage many left behind in the transition from agrarian to urban realities. More than that, I believe these stories have the power to connect people across racial and ethnic lines, and to create a table where we are all at once welcome to finally sit and partake of the fruits of our ancestors.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.3 (April, 2011).